The Destruction of Buildings in London, 2010-2012

—

The destruction of buildings in London, 2010-2012

‘“Let the protector of a landholder be a landholder; for one of the proletariat, let anyone that cares be protector.” - anonymous Italian lawyer, 2,500 years ago. (The Law of the Twelve Tables.)

The study of the loss of a building, of its end, is for me the starting point for a negative history of technology. If histories of technology generally show how a man invented a machine, similarly histories of buildings in general show how one man - the architect - ‘built’ an object. In manufacture, buildings are a specific kind of technology which brings together different kinds of labour in one place, in as much as they allow a commodity to be worked on by different hands with the minimum transport costs. Living labour is combined and produces the petrified dead mass of its own efforts, so-called dead labour. The buildings which house this process are also, themselves, dead labour, and a kind of machine, even if the commodity they help to produce, as with houses, is nothing less than the labour power of the worker herself. A critical history would show how many people, a collective body, invented those buildings which sustain life under capital. Consequentially, a critical, negative history of technology would show how that collective body has broken the machines which sustain life. It is aspects of that critical history which I now want to sketch out.

Marx wrote that the whole history of the development of machinery can be traced in the history of the corn mill. That statement it seems to me stands true not only for the history of machinery, but also of its destruction by the very consumers its establishment was meant to benefit, at least according to the standard of liberal political economy. The history of resistance by the English working class is filled with the demolition of mills, from the Peasant Rising of 1381 down to the sleighting of Royal mills during the Civil war. The figure of hate was the middleman, the profiteering miller. In the eighteenth century, the first co-operative run flour mills were established by dockers in Woolwich and Chatham. Each docker owned a share of the mill, and controlled it by an elected committee, putting the decisions, as well as the finances, in control of the consumers, thereby cutting out the middleman. Grain shortages in the Napoleonic war spread the appeal of cooperatively owned corn mills, and the utopian yearning escape the world of capitalist competition expanded the co-operative movement mills to shops. The profit made from such stores was fed back into the communities of the workers who owned them, for education institutions, libraries and community centres. In this way, the cooperative movement contributed significantly to the infrastructure of the labour movement in the late nineteenth century. The English Co-operative Wholesale society had sales amounting to £4.5million in 1883, and the Socialist Co-operative Federation was running stores in Battersea, Chelsea and Tottenham. Cooperative Party, the movement’s political wing, was also gaining ground. In the miners’ strikes of the 1920s, co-operative societies up and down the country acted as the material and financial support for strikers’ families, ultimately leading to over a million pounds of debt by the end of 1926. Nonetheless, in celebration of the leaps and bounds the co-operative movement was taking, the head of the London Co-operative Society, Alf Barnes MP, oversaw the construction of a grand new headquarters for that organisation replete with a lavish co-operative department store in Tottenham, named ‘Union Point’.

The construction of bravado was in vain. By 1933 the Labour Party, now in power and aware that the Co-operative movement was weighing on the coat tails of their trade union comrades, introduced taxes on the cooperative bank’s reserves. After the war, the Co-operative society slowly crumbled as multinationals undercut the retail arm. By the early 1960s, the London Cooperative Society faced an existential crisis. In the 80s the department stores closed down. By the early 90s, the ground floor of the building was given over to the kind of monopolistic supply chains against which the society had always railed. Allied Carpets and Doors, later Carpet Right, proudly blazoned their signage across Tottenham High Road. On August 11th 2011, the Union Point building was burnt down. Thousands of residents of Tottenham and Edmonton charged through Tottenham High Street. Debt and deferred wages, combined with the lack of any state-resource to enforce austerity measures save for the single glorious mechanism of the police, were visited back upon the building which had for decades monitored the transformation of consumer co-operation into a mass consumer debt economy.

The cooperative movement had proposed a mode of consumption based on working class identity and solidarity, counter-posed to a form of consumption which has come to be known simply as ‘mass consumption’. In 2011, both of these modes of consumption confronted another, even older version: the mob. Here are the words from one young man who participated in the 2011 rising:

“No one’s got no money around here so everyone’s trying to make as much as they can while they can. Obviously people who say we’re thieves have got a lot easier lives than other people around here. Some people have got absolutely nothing. The destruction is just consequences that happen when everyone teams together.”

That idea of “everyone teaming together” is anti-production as cooperation; the negation of fixed capital by pure human sociality, offered up in the name of consumption. Gordon Thompson, sentenced for eleven years for his part in burning down a Croydon furniture store called ‘The House of Reeves’ was held up as a single figure for the effects of such cooperation. After the windows of the building had been smashed Thompson ran in and grabbed a laptop, then set fire to a sofa with a cigarette lighter. What amplified the small technology of the lighter into a combustion which was so intense that it took with it not only the furniture store but also neighbouring houses, was that the fire service refused to go near the conflagration so long as there were no police there to support them, and what was keeping the police busy was other rioters.

“The destruction is just consequences that happen when everyone teams together.” Cooperation of that kind has no fixed capital. It does not exist in a building but outside of it. It resists all attempts to be brought into one space - just think of all those outrageous failures by so many groups - from the Tottenham Defence Group to the Metropolitan Police to the Socialist Workers’ Party to ‘Reverse the Riots’ - to bring the rioters together again, whether for laudation or discipline, empowerment or simply subsumption. The mob resists those attempts structurally, through law, politics and economy. The technology simply does not exist to make that combination occur again with ease. All the capitalist need do in order to reassemble his workforce is pick from the full range of coercive technologies of the market - in the main being wages - and combination appears infinitely reproducible. But the combination of a mob always finite.

The sudden fire and smashed windows, the shudder of Tottenham, is in marked contrast to the more usual, packaged version of architectural deterioration which focuses on decay and rot instead of smash and grab. There are a number of housing estates which, if you talk to architects, their students, journalists and housing campaigners, have this narrative of decay and regeneration constantly visited upon them. First up is always the Heygate Estate, then the Aylesbury, Carpenters, Woodberry Down, Gibbs Green, Kidbrooke, Pembury and Packington. The image of disrepair, a state into which London’s housing estates of the 1960s are increasingly said to have fallen, has slid its way through the artists’ camera lense and out into our film screens and sunday supplements. But despite all the tears shed over the poor, vanishing housing stock, this image really serves to emphasise a conception of dragging, evolutionary historical change. The moss grows thick, the lichen spreads, a community is slowly broken up. Contrast this with the riots of 2011 when there was an aliveness and tension in the air as everyone waited for something to happen, and that feeling of glue being sliced apart as the impossible actually did take place in an instant flash, not a slow transformation.

There is a real and material benefit to the popularity of such images of decaying estates, which help to foster impressions of the imagined criminality and lasciviousness of their inhabitants. This ideology is of benefit not only to the financing developer desperate to push the current residents out and the plate glass in. Such tales of inevitable, slow decay are also of benefit to the lobbyists for an industrial sector which wants to speed up the destruction itself. The housing estates, homes which have been specifically built for working families collide with the waged demolition worker. Destruction becomes a form of profit and variable capital, in that it is through managed destruction of accumulated, manifest dead labour that capital manages to exploit living labour yet again, through a whole industry of destruction, construction and redestruction which further comprises the web of history manifested in buildings as they stand.

That history can be understood as an emotive nostalgia, but I think this is a mistake. If cooperation is the transmitting mechanism which magnifies the tools of destruction, then the motor mechanism is the oppositional, antagonistic content of the objects which are being destroyed. This understanding burrows through the subterranean arena of materialism and out into the realms of common sense as the ‘emotional’ content of objects. The emotional damage of dragging people from their homes, evicting them through the combined means of affidavits and bailiffs is played on by the sympathetic as a way of propagandising against the machinations of politicians. But the psychological econometrics of destruction are measured not only by the evicted and dejected in appeals for exoneration, but also by the apparatchiks of law. Last April, in sentencing Gordon Thompson for the burning down of the ‘House of Reeves’, Judge Peter Thornton made this aesthetic pronouncement:

“The Reeves family lost their historic business, something they and generations before them had lived and worked for all their lives. The loss was priceless, the trauma they have suffered inestimable.”

This recourse to emotions is an important part of hiding the economic realities of destruction, because for the police, a few months wouldn’t be punishment enough, and that is all that property damage would return. Emotional distress allows the violence to have been perpetrated against people, and the resultant sentences to be stretched out. This levering of emotions from the destruction of buildings is not what should be achieved by a history of destruction, as it is no more than a reflection of the idea that all objects carry with them the emotions of their owners, the projected affective fragments of a legally constituted entity. I want us instead to think about the buildings which fall around us through acts of destruction as more than simply commodities in this polite bourgeois sense, but as the accumulation of sweat and tears, of the vast swathes of work which brought them into being. It is the force of this heaped up work and human energy-passed which we have to work against in order to bring the foundations of these structures around us out from the earth and into the rubble.

In November 2010, number 30 Millbank, the broad low building next to the tower, was attacked by around one thousand people. In the immediate moment, in those hours among the shards when Millbank was smashed in, it was quite unclear what was happening. That crowd is usually described as having been comprised simply of students, but this clearly tells only one very limited story about how the glass of Millbank came to be smashed in. The building was attacked, but really the foremost destruction was only of plate glass and cctv cameras. The rest of the structure seems irrelevant. The cameras immediately outside the building recorded the photogenic camera smashing inside, and a breaking apart crystallised into a snapshot. Again, the police leant on the witnesses of the destruction to dig up the emotional damage caused by the mob. Thus one witness account from an administrator in the Conservative Party’s ‘Human Resources’ department wrote this of the evening and next morning immediately after the Millbank attack:

“I got home about 8pm. I had already rung my husband to let him know what had been happening and he realised how upset I was. When I went into the corridor leading up to my flat, I felt very wary and jumped thinking someone was following behind me. It was actually just my rucksack. I didn’t sleep well that night. I got the bus to work and when I arrived I saw all the damage that had been done and the offensive, abusive graffiti. A lot of this was directed at the Conservatives - it seemed like pure hatred, and I felt personally upset by this as I work for the Conservative Party.”

The mob not only partially destroyed the building, but also in doing so burst through into the nightmares of its inhabitants. The tradition of living generations weighs like a rucksack on the backs of the Tories.

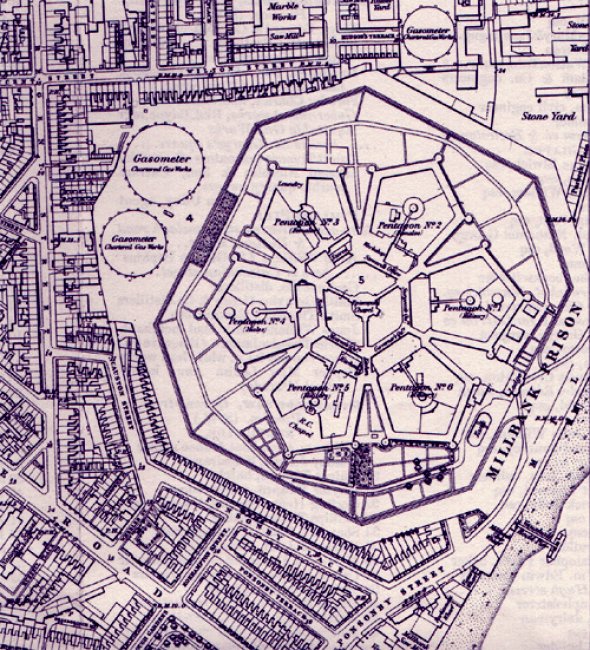

What is the material history which brought that mob to that building on that day? Millbank, of course, still stands. The name is taken from the medieval mill powered by the Thames which serviced Westminster Abbey. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the site was bought by the state, under the advice of Jeremy Bentham for the realisation of his Panopticon in the form of the National Penitentiary. The marshland on which it was built only helped to create dire conditions for the prisoners, as disease was rife. After the prison was decomissioned and demolished, its bricks contributed to the construction of the London county council’s Millbank housing estate. The poorer housing on the Chelsea embankment was destroyed in 1928, however, when a combination of heavy snow and dredging of the Thames to make way for new, larger industrial vessels, led to mass flooding. But profit ensued from the destruction in the end: the reconstructed embankment allowed for the very edge of the river to become prime real estate. In 1963, the new tower for an arms and steel company called Vickers Group was built, using new stainless steel from Union Carbide and the Morris Singer foundry.

Not long after its completion, the panoramic views from the head office would have belonged to Alfred Robens, the new director. Robens had started his career as a Director of the Manchester and Salford Co-operative Society, but moving through the Labour Party ranks was installed as chair of the National Coal Board through the 1960s. In 1971, under pressure from a Tory administration, Robens left this position, and redirected his energies into the Directorship of good British arms manufacture. Characteristically for this political flip-flopper, Robens vehemently opposed the Labour government’s plans for nationalisation. Despite this opposition, in 1977 Vickers was incorporated into British Aerospace. Only a few years after this, under the Thatcher government, the state sold 51% of its shares in the company and it was given its obligatory three letter acronym for the stock exchange listing by which it is now known: BAE.

The history of the Millbank tower - perhaps we should call it the BAE tower - charts that of variations in post-war production in its shift from providing a steel casing to private British industry, then to state controlled production and then, those assets sold off almost as soon as they were accrued, the tower itself moves into the boom sector of real estate and the seeming immaterialities of finance and mass media. Over the years, the Millbank Tower complex has been host to both Labour and Conservative Party headquarters. The shift has simply been from milling to spinning things just down the bank from Westminster. It is currently owned by the Reuben Brothers, a duet of venture capitalists who made their money investing in metal and, after extracting as much of their previous investments as they could from recession hit Russia ten years ago, have bought up many of London’s more prominent buildings. Their investment arm, Motcombe Estates, owns the building, which employs a company called CB Richard Ellis Property to oversee its workings, the managerial labour of which is entrusted to a salaried employee called Simon Moxley. Here’s his account of that day in November 2010, as extracted from his witness statement for the police:

“Almost immediately a large plate glass window to the right of the doors was smashed from outside. […] I could see thousands of protesters outside and they were trying to get into the building. I would describe the situation as hostile. I served as a soldier in Northern Ireland in the 1980s, so I am fully aware of what a hostile crowd is.”

Faced with having to explain the situation to the English judicial system, Moxley, the representative of capital, reaches for a favoured, centuries old allusion of fear and prejudice: the Irish mob. You can change the business inside the building all you want, but large steel and glass buildings like Millbank will always be faced with a mob of that kind and its correlating portrayal. If, in piecing together the history of the Vickers building I have managed to make it a representation of both privatisation and militarisation, this should come as no surprise, for large pieces of fixed capital require finance, privatisation is a main tool of that finance, and militarisation a primary method of accumulation. In other words, fixed capital has its fanbase. It isn’t a coincidence that in tracing a history of buildings destroyed by proletarians you find a cumulative history of the methods of their immiseration, simply because large pieces of fixed capital are never, under the current mode of production, destroyed without the labour activated for their manifestation being dragged back through history and into the fire.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com