Zombie Nation

As the scarcity essential to the cultural commodity is undermined by digital abundance and social networking, social relations and the unique ‘live’ performance are all that's left to sell. Mass market music increasingly resembles relational art with its dream of waking the ‘zombies’ of consumer culture, but are the citizens of Web 2.0 society born again or undead? Paul Helliwell shuffles through the mall

That which determines subjects as means of production and not as living purposes, increases with the proportion of machines to variable capital… its consummate organisation demands the coordination of people that are dead.

– Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia

I thought that beauty alone would satisfy. But the soul is gone. I can't bear those empty, staring eyes.

– Charles Beaumont in White Zombie

Too often people are happy drawing up an inventory of yesterday's concerns, the better to lament the fact of not getting an answer.

– Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics

In my previous article for Mute, ‘First Cut is the Deepest’ (Mute Vol2 #4), I talked about a panglossian enthusiasm for the social in art, courtesy of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics. This enthusiasm for the social is not confined to art – where Adorno describes it as the means by which art expresses its own uncertainty – but has become the motor of modern capitalism, one example of which is Web 2.0. For this reason music is thrust centre stage both as a means and a metaphor for unproblematic sociability and communication – from a recent mobile phone ad selling its music player by insisting ‘there will be one song that will get you to phone home’, to the opportunity to listen to music inspired by the abstract minimalism of Donald Judd at the Tate Modern. In the same room as this event, we are moved along the curatorial time-line from Ad Reinhardt’s stripped down modernism (that Adorno would recognise), to the dawn of relational aesthetics, with the mirrored surfaces of Robert Morris incorporating you the viewer in the work. ‘You’ can also be seen in the mirrored cover of last year’s Christmas issue of Time magazine, declared person of the year for your sterling unpaid work on Web 2.0. But sociability, even the kind produced by music, has never been unproblematic for power, as the essentially disciplinary nature of the discourses around the crowd and music reveal. At least until now. So what do art, music and Web 2.0 have to say to each other and about us?

In commercial TV, wealth is circulated in two subsystems – one that produces the programmes and sells them to TV companies, and the second where TV companies sell the viewers watching them to the advertisers. Web 2.0 dispenses with the first subsystem; you provide the content for free, leaving only the second need to ‘monetise eyeballs’ in MySpace co-founder Chris deWolfe's parlance. These eyeballs are doubly monetised because they also provide the basis for the stock market values of companies currently sucking in the dumb money (preparatory to rinsing it out). Several Wall Street finance houses encourage the reading of Charles MacKay's Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds with its histories of Tulipomania and the South Sea Bubble, so that staff recognise the system is irrational and unstable. It creates profits because it is irrational (as long as faith is high the value remains high) and unstable (as soon as it goes value collapses), it is a pyramid scheme (the smart money takes the difference and later the dumb money pays). If it were only the value of the work of western ‘creatives’ being rinsed out (and more and more of the work of the West is in these unstable intangibles – brand, goodwill, design) it would not be such a tragedy, but capitalism is a global system.

This new sociability of Web 2.0, hosted on big corporate owned servers, is the defeat of an arguably better working and more democratic ideal – peer-to-peer, strangled in its musical infancy by the not so invisible hand of copyright. Napster may be back from the dead and charging, but the music industry's worst nightmare – free music – is still on the prowl, its defeat is partial and temporary. In the long run, with digital copying and distribution effectively free it is difficult to see how it can be otherwise. It is no surprise to find that MySpace is a direct response to peer-to-peer’s ‘defeat’ and the changes a new format has brought about in the music industry. Indeed it may be the prototype for further strategies of control for software, films etc.

Chris DeWolfe says the following:

Tom [MySpace co-founder number 2] … [understands] … what emerging musicians go through. He understands the frustration. I understood the macro trends of the music business. Labels were signing fewer acts, giving them less time to prove themselves and spending less money on marketing. We saw a need to develop a community for artists to get their music out to the masses … In the early days, there were a lot of bands signing up …

Deepening the work of Jacques Attali, Michael Chanan shows music as a constellation of antagonistic technologies, markets, commodities and services repeatedly pulled apart and remade by new technologies (from musical notation and printing, to analogue recording and broadcasting). The combination of music software, peer-to-peer and MP3 (going beyond radio and cassette before it) threatened to unleash a world of free music, by uniting the recording, promotion, distribution and consumption of music in one machine (the home computer). This led to a fight between the large multinational electronics companies producing the computers and MP3 players, and their subdivisions marketing the recordings, owning the copyright or managing the artists. The record companies lost and are fighting a rearguard action. Unlike the vastly profitable days of CDs, when record companies could be subsidised with new money made by re-releasing old material in the new formats, profits have fallen drastically and more bad news may be on the way.

As with many new technologies, the founders have not understood the transformation they are unleashing. Bands were actively recruited by MySpace as ‘early adopters’, they chose it as a promotional tool (into the music industry) but also because they claimed to want a more direct relationship with their fans outside of the record companies’ control. MP3, by calling into question the economics of the music industry, has revealed the chronic dissatisfaction of artists, songwriters and producers. A dissatisfaction of which they will be doubly free, for soon this relationship will be all that bands have left to sell to their fans. The apparent defence of copyright by the music industry masks its relaxation – on MySpace, on YouTube. Paying for the right to make a copy is what makes music a commodity – fans demanded an extension of the right to make a copy as ‘fair use’ and they got it.

Recently at MIDEM, the music licensing conference in Cannes, Jacques Attali joked that other than playing gigs soon all that bands will be able to sell is the right to attend a rehearsal or go to dinner with them. He was immediately handed a business card for a scheme enabling just that [www.artistshare.com]:

[participate in] the one thing that cannot be downloaded … that the artist can hold on to … the creative process [sic].

The demand to pay for music is being resituated as active consumption – if you love your band you’ll pay. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the future of the music industry, it is, in its lack of anything material to sell, relational aesthetics, and the institution that will enable this is not the record companies or the art galleries but Web 2.0. The moral of the story is be careful what you ask for.

A fetish for ‘liveness’ pervades recorded music’s last hours as commodity, from the downsized calculated naiveté and acoustic instrumentation of new folk and singer-songwriters, to the live show – formerly an expensive means to advertise the CD, but now the one means bands have to earn money. Music fans habits have been conditioned by scarcity, the need to collect – what happens when this era is over? A whole industry has fossilised round this habit, it will take time to go whether it fights or not. The surplus of recorded sound on the computers of the world cannot be potlatched because to make a digital copy does not destroy the original or reduce its value. Music cannot even be given away because nothing is lost, it can only be shared in the weakest sense of the term. The CD is beginning to look like so much landfill, and has already been pronounced dead by the departing head of EMI. Why even download anything when you can stream it? Recorded music is dematerialising beyond even the MP3 on your hard drive.

The relationship of music and art affects the light they throw on each other. Both have their origin in magic and in cult and have separated themselves (by becoming commodities and developing formal autonomy) and become the autonomous discourses that we currently know. During the 20th century, music, through recording, embraced reproduction and thus became mass culture, seemingly stripped of its autonomy; merely a commodity. Art defined itself in opposition, insisting on its aura, on its autonomy, its commodity nature hidden. At the same time, art, in denial of its commodity status, tried to free itself from its autonomy with conceptual art, performance art, relational art, all leading to the evaporation of the art object into the one-off happening (but this was no barrier to the documentation being successfully commodified).

Recorded music is most often consumed a-socially (via the CD played in privacy, the walkman, the MP3 download), but its logics of consumption continue to be social (the Top Ten, pirate radio shout outs, the distorted MP3 on the phone on the bus). Web 2.0 is no different in its logics of consumption. It is awash with counters, Top Tens, customers who bought this also bought, algorithms designed to predict what would appeal to you, a need to affirm some kind of community, to introduce the possibility of a chance encounter or a serendipitous discovery.

Zizek has written on the psychological dangers of blurring real and virtual identities, but perhaps another danger lies in online counters functioning as pecking orders. MySpace (a place for friends) just IS a giant popularity contest (Rank User – has no one seen Carrie?); this is the sole criterion and validation. Indeed this extends to news stories about it which are nothing but ‘so-and-so is becoming very popular’. The actual experience of MySpace is of slow uploading, fending off the advances of strangers with 970 friends (surely that's enough?), Truman-show style viral advertising (this week I'm listening to…), kudos counters to help you fine tune your product, but above all social anxiety (only 5 hits – I must persuade my friends to join). The thin line between this and vanity publishing risks the exposure of our ignoble motives. All this encourages self-reification with a Skinnerian thoroughness.

Social networking websites are experiments, like the relational art Jacques Rancière identifies as the invitation/encounter, the use that will be made of the site cannot be predicted. One of Bebo’s [http://www.bebo.com/] founders describes the problem as like inviting people to Welwyn Garden City – it's artificial so it wont grow unless it is ‘seeded’ and ‘nurtured’. Almost all will emphasise that they don’t want to be ‘over-controlling’, yet these are family malls, almost all ban pornography (before music, the motor of Web 1.0). James Wales of Wikipedia likens its constitution to the unwritten one of the UK that evolved over time, and fellow developers insist they build what the users ask for. What people ‘ask for’, even for themselves, is made over in the image of the commodity, and every click is marketing information. Given the fink link on each photo – ‘report inappropriate image’ – it is a more controlled environment than any shopping mall.

When Jaron Lanier calls Wikipedia and much of Web 2.0 ‘Digital Maoism’ we know we are into a rerun of modernist disdain for the masses. Jaron attempts to hook us in by presenting himself as wronged by Wikipedia which persists in describing him as a film maker, when he has repudiated his Maya Deren phase and would prefer to be known for his term ‘virtual reality’. He changes it, someone changes it back (an ‘edit war’ but, though he doesn’t say it, he’s being ‘cyber-bullied’). To my friends, however, Jaron is the man who beheaded Sony's robot cat at the ICA by picking it up by the scruff of the neck. This is Gombrowicz’s ‘interpersonal form’ (see ‘First Cut is the Deepest’, Mute Vol2 #4), the extent to which we are created by others, which Bourriaud claims as the substrate of relational art. Despite this Jaron is unhappy to be misrepresented and allowed no recourse, as was Gombrowicz. He is clear the ‘collective intelligence’ harnessed in Web 2.0, the counters, the meta-searches compiling ‘best-of’ lists, just generates stupidity, that having large sites visited by everybody just generates traffic jams on the internet.

In comparison cyber-theorist John Brockman is the Elias Canetti of this generation of crowd theorists pointing out that crowds can (sometimes) be good. In his version ‘Here Comes Everybody’, the masses do not simply invade the net, they are also changed by the experience. But this is no more to the taste of the digerati (with their evolutionary systems, algorithms, positivism, signal processing metaphors and fetish for salons of ‘smart’ people) than it was to the 19th century intellectuals (ditto…) at the birth of mass culture. John Carey in his The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880-1939 points out in this steampunk version that the masses were symbolised by tinned food (a crowd metaphor that Canetti would recognise), and this image recurs in the digital age as spam. Monty Python’s song echoing in the sound of senseless repetition clunking onto your hard drive. Indeed, like the fertile text of Gogol’s Dead Souls, the new blogging tools enable the creation of fictitious people with fictitious opinions – splogs or blams. It seems that no sooner has man created a new digital environment than it starts to be swamped like some re-run of the magic porridge pot (and, again, the moral of the story is ‘be careful what you ask for’). In digitally reproduced excess even human opinion becomes toxic.

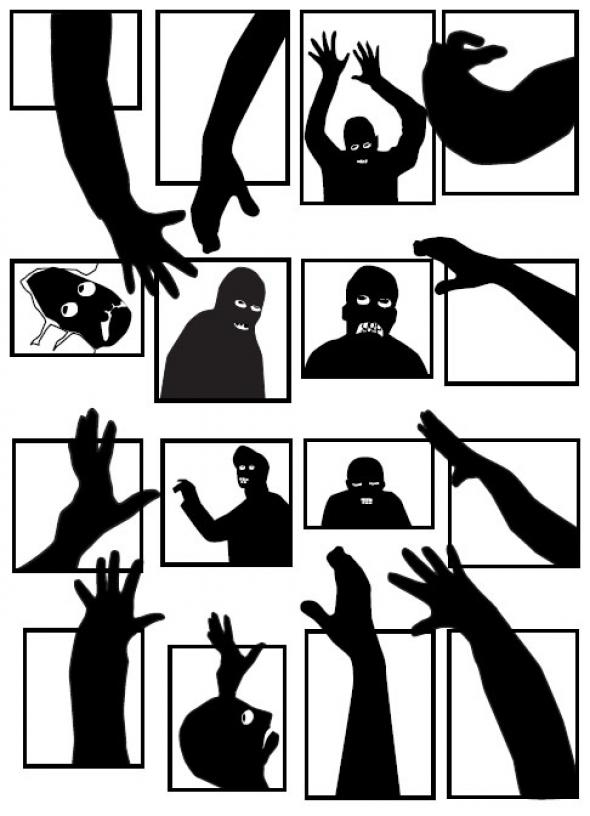

In his introduction to Intellectuals and the Masses, Carey surveys modernist theories of the mass (José Ortega y Gasset, Friedrich Nietzsche, and more narrowly on crowds – Gustave Le Bon and Sigmund Freud) and finds them overwhelmingly hostile – so hostile in fact that he can only read Canetti’s enthusiasm for the crowd as inconsistent rather than oppositional. For Canetti, the desire to become a crowd is something fundamental to humans (perhaps their species being), and is often achieved through music, from the symphony orchestra to the Maori’s Haka war dance. Canetti's autobiography reveals two things that encouraged him to think about crowds as if they had a will of their own. One was being part of the mob that burnt down the Vienna Palace of Justice on 15 July 1927, (fire – another great crowd metaphor), the other was Pieter Breugel’s painting The Triumph of Death in which thousands of skeletons, formed into armies and churches more vital than the living, pull them over into death. This is where we first meet the modern crowd metaphor par excellence – the crowd of the dead, the legions of the damned, the humble zombie, – and yet until recently they were a sluggish lot.

The term zombie entered the English language as a result of slavery, in Robert Southey’s History of Brazil. William B. Seabrook’s book The Magic Island, a first-person account of Haitian voodoo rituals (like Maya Deren’s much later Divine Horsemen), inspired White Zombie, 1931, the first zombie movie. In this we see a sugar plantation owned by Bela Lugosi and staffed by zombies. One of the shambling beasts falls into the grinding machinery and becomes at one with the product. This images anxiety about stolen labour on the part of both producer and consumer embodied in what at once unites them and keeps them separate – the commodity. By 1968 and George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, filmed in de-industrialising Pittsburgh, their passivity was the passivity of the mass non-violent resisters campaigning for civil rights. They lumbered because they were inevitable, the mass in human flesh to be sadistically destroyed, interested only in increasing the number of zombies – apocryphally by eating their victim’s brains. By Dawn of the Dead, 1978, their very existence is overproduction: ‘When there's no more room in hell, the dead will walk the Earth’ – zombies were the proletarian dead proletarian shopping. ‘But why have they all come to the Mall?’ asks one of the living, ‘I don't know… I guess it must have meant something to them in their lives.’ For Web 2.0 users, like the human survivors in Dawn, incarcerated by the zombie hordes in a shopping mall where everything is free, this anxiety of stolen labour can only increase (despite the muzak). Beneath the glossy reflective surface of the commodity is putrifying zombie flesh – humanity is not superfluous in the age of globalised production but only its ‘creative’ part is recognised (leading to its haunting by the latest in a long line of unquiet Marxist spectres).

From White Zombie onwards film makers unerringly return to music to suggest the lost echo of humanity (as if there were a song that could bring the dead back to life) – the scene from which I quote in the epigraph of this article, like its equivalent scene in Blade Runner, is of a man and a woman at a piano. In Day of the Dead, a later Romero movie, the remnants of humanity are hidden underground trying to train the zombies to do useful work by means of conditioning à la B.F. Skinner’s fictional behaviourist utopia in Walden Two. The zombies are often left unattended listening to classical music on their walkmans – one perks up and begins to sing along, but then loses the signal and is a zombie again.

Movie by movie the zombies are getting more like us, or at least faster and smarter. In exile from Hollywood, zombie maestro George Romero is in Ontario filming a straight to DVD release with a hand-held DV camera – Diary of the Dead. Yes, there is a MySpace page, but the one prediction I’d make is that by the end of the film the zombies will be filming it (and posting it up like the cannibal happy slappers they are).

It is important to move our understanding of zombies out of ritual denunciation. There is pleasure in zombiedom and it lies in an infantilisation, in a Svejkian resistance, in an inability to respond fully to the social imperatives of advertising and shopping: a zombie’s eyeball may be in or out but it cannot be monetised. Indeed there’s even a variety of flashmob called a zombie walk. In the largest of these to date, on 29 October, 2006, 894 participants gathered at the Monroeville Mall in Pittsburg, one of the first big malls and the set of Dawn of the Dead. The flashmob, an activity originally intended to satirise crowd stupidity has, in succumbing to its undoubted pleasures, become a critical practice.

I started in an art gallery so I’ll finish there (they’re getting to be popular places as the fetish for creativity spreads). In Windsor, Ontario, the locals are embarrassed that their town gallery is in the mall. They shouldn’t be, for the art we now possess is entirely made over in the image of the commodity, the only model for cultural life we have left. And yet, as Adorno also argues, Art’s Autonomy remains irrevocable. All efforts to restore art by giving it a social function – of which art is itself uncertain and by which it expresses its own uncertainty – are doomed. In the mid-1990s, at Bank’s show Zombie Golf, plaster cast zombies of the artists wandered round the exhibition space demanding brains. Dave Beech and John Roberts regarded them as simultaneously standing for both the spectre of a repressed aesthetic ideology haunting art and its negation. Art may attempt to finish with it, but aesthetic autonomy has not finished with art.

For Adorno, art in its autonomy reveals its character as surplus labour, produced to meet no real need at all. What is good about art is that it is useless, it is exchange value without use value, it is an ‘absolute commodity’. Thus, unlike any other commodity in capitalism, it does not pretend to be of any use and so reveals the excess of products and services round us as likewise useless. Many find this autonomy, or uselessness, deeply disturbing, and wish to get rid of it and give art a use. They do not see this autonomy arising from art’s heteronomy (as Adorno does) but as sealing off art within itself – hence art’s embrace of non-art is regarded as more hopeful than it really is. For Adorno the production of a work of art cannot be outside capitalism, thus it cannot be produced to meet true needs (as in an artisanal model of production), for no theory of true needs yet exists. Modern art became abstract because of the waning of experience under capitalism (commodification, the dialectic of enlightenment) and cannot directly compensate for these losses. However, art is nothing if not historic material, it is not enough to abstractly negate relational aesthetics as a category and so wish it away, it must be dealt with on its own terms.

For Bourriaud, autonomy and sovereignty are simply ‘yesterday’s concerns’, they have been ‘wound up’. Relational aesthetics claim to be heir to an irrationalist tradition (dada, the surrealists, the Situationist International) that resists instrumental rationality’s occupation of the social – the dialectic of enlightenment. That rationality is so successful it destroys all cultural practices constitutive of the human, reducing us all to zombiedom. For Bourriaud in considering the place of artworks in the overall economic system, ‘the work of art represents a social interstice’, a place where the normal laws do not run, explicitly in resistance to this occupation, an art that does not respond ‘to the excess of commodities and signs, but to a lack of connections’ by ‘performing small services in an attempt to restore the social bond.’

What about relational aesthetics? Can it actually do what it claims? Is it a critical practice or merely an aesthetics and an art for the service economy.

Look at the Tate’s State Britain exhibit which is poised on this precise point. Peace campaigner Brian Haw’s Parliament Square protest was begun in June 2001 against the economic sanctions in Iraq. Parliament’s ‘Serious Organised Crime and Police Act’ banned unauthorised demonstrations within a one kilometre of it (ah, that evolving British constitution…) and the majority of Haw’s protest banners were removed by the police on 23 May 2006. Mark Wallinger has recreated the demonstration in Tate Britain. For Adorno, the police need not come (again) precisely because it is art and its autonomy remains irrevocable. Yet in Adorno’s work, perhaps, the heteronomy from which autonomy derives is a regulative concept, something he’s not really interested in. For Jacques Rancière there are heterogeneous logics between the forms of art and the forms of non-art, between the two opposed politics of aesthetics; that art either becomes life by not being art (perhaps the political art of the banners themselves), or it does politics by explicitly not doing politics (perhaps the other art in Tate Britain within the 1km zone). For critical art, the realignment of these logics between the art of politics and art with neither side sacrificed is achieved by this collage/juxtaposition. If State Britain did not cross the line into the 1km exclusion zone, this recreation of politics would be no more a critique of power than Fischli and Weiss’s recreation of their own studio – only troubling to the extent it is an uncanny double, a zombie. But in crossing the 1km exclusion zone line the artwork may have been sacrificed to politics. And yet even as it is denied or questioned art’s autonomy is being relied upon to create political meaning.

The juxtaposition that is relational art itself has become problematic even to its supporters. Claire Bishop wants good works of art rather than feel good/do good works, to prevent sacrificing the aesthetic to the relational. Conversely Grant Kester seems to want this sacrifice, he wants out from under the aesthetic of art criticism.

The founding of the Arts Council at ‘an arms length’ from government shows that there was a time when the autonomy of art was explicitly required. Yet, if Bishop and Kester agree on only one thing it is that what the Arts Council requires of art now is ‘social inclusion’ and ‘value for money’ – a much more clearly instrumental role for art in delivering government policy – and that relational artists have become complicit in this, drawn in by the shrinkage of both real and discursive public space, by the deficit of politics. In its need to incorporate ‘you the public’ in the work, relational art makes itself useful by attacking the autonomy of the public, driving them into the arms of institutions for funding. Relational art sells its audience to power as crowd control. Kester’s group, Littoral arts still think there is mileage in relational aesthetics through more collaboration, surrendering more to politics – to trade union funding for instance. The people who sell you, ‘the variable capital’, to capital.

In her article ‘The Ethics of Aesthetics’ (Art Monthly, March, 2005), Sarah James critiques Bourriaud’s thesis for ‘its complicity with the dominant political status quo’, and also notes a return of Aesthetics as a concern of art. But is this return ‘acquiescence to political entropy’? Just a return to the demand that art produce something beautiful (for sale)? Art has been at war with its autonomy, but its status as absolute commodity (exchange value only) has gone unquestioned and this contains its own dangers – that it may become the model for the rest of the economy. Just as art is heading out of relational aesthetics it seems music and capital are piling in.

References

Jacques Attali, ‘Ironie du Virtuel’, L’Express, 21 January 2007, http://blogs.lexpress.fr/attali/

Dave Beech, ‘Chill Out: Dave Beech On and Off the Politics of “young British art”’, 1996, http://easyweb.easynet.co.uk/~giraffe/e/hard/text/beech.html

Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents’, Artforum, February 2006, http://www.artforum.com/ — but you'll have to register. Sadly I can't get hold of Grant Kester's subsequent reply online.

Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, Les Presses du Reel, 2002.

Jennifer Roche, ‘Socially Engaged Art, Critics and Discontents: An Interview with Claire Bishop’, July 25, 2006, http://www.communityarts.net/readingroom/archivefiles/2006/07/socially_engage.php

Also see Leisurearts for a blog discussion of the debate between Bishop and Kester: http://leisurearts.blogspot.com/2006/05/grant-kester-artforum-claire-bishop.html

Grant Kester, ‘Dialogical Aesthetics: A Critical Framework For Littoral Art’, Variant, issue 9, Winter 1999/2000, http://www.variant.randomstate.org/9texts/KesterSupplement.html

Jaron Lanier, ‘Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism’, Edge, 30 May 2006, http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/lanier06/lanier06_index.html

John Roberts, ‘Home “Truths”’, 1996, http://easyweb.easynet.co.uk/~giraffe/e/hard/text/roberts2.html

Ian Katz and Oliver Burkeman, ‘The Web Revolutionaries – the Men and Women Who Reshaped the Net’, The Guardian, Web 2.0 Special, 4 November 2006, http://www.guardian.co.uk/video/page/0,,1942132,00.html

Natalie Pace, ‘Myspace Conquers Google: Takes on World Exclusive Q&A with MySpace Co-founders Chris DeWolfe and Tom Anderson’, Natalie Pace.com, Vol 3 Issue 1, 1 January, 2006, http://www.i-sophia.com/newsletters/members/news.php?np=yes&issue=301/301&article=01

Claire Bishop, ed., Participation (Documents of Contemporary Art), Whitechapel, 2006.

Edward Halperin, White Zombie, 1931, is out of copyright and downloadable for free at: http://www.archive.org/detail/WhiteZombie

BiogPaul Helliwell <phelliwell2000 AT yahoo.co.uk> would like to thank Martin Denyer for his assistance with this article and to direct people to the MySpace site of his 'brother ass', horsemouth:

http://www.myspace.com/horsemouthfolk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com