Postscript (p.s. Forever)

If all surfaces and gestures are mediated by capital, how can we imagine them becoming a ground for struggle? An experimental text by Rózsa Farkas and Harry Burke

This text was commissioned by Charlie Woolley for his recent show, Postscript (p.s I Love You). Part one of this text can be found here: http://charliewoolley.hotglue.me/?psiloveyoutext/

1:

Sometimes I wonder if you really, really want things enough they will happen. Like if you wanted the end of capitalism so much that it just happened. Not sure what you’d do at that point but still, how about that for rupture. Sitting on your sofa with so much desire that the world changed. Impotent desire is bleating at me, saying that there wouldn’t be a sound or anything, you’d just know. But what’s funny is that if everyone thought like that, if everyone actually did want the end of capitalism, it could maybe happen, if desire lost its inertness. Weird. Like the time I decided to stop loving you, lol, just sitting in the exact same place. I wanted everyone to stick their heads out of their windows and scream: ‘I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more!’ But that’s the point, it was just a decision, the world didn’t change. You look out into the street, it’s basically the same, the same as it was always.

2:

2013. A platform of performed sociality on Come Dine With Me plays in the background, a pleasantly consumable mise-en-scène. It has been orchestrated to include an Englishman’s version of a passionate Brazilian woman, conversationally fencing with a man, who is irritating because of his imbibed, prescribed knowledge, regurgitated with uncharitable self-righteousness. Although in conversation, his tales of his social justice on the 4th Plinth are not directed toward the ‘threatening Latina’ (or propagator of sexual bravado positioned opposite him), but are instead a waste souvenir fan, flapped for the benefit of the other guests, a desperate attempt at male domination across a shepherd’s pie. In a clumsy flourish she shuts him up by stating she would get up there, strip off, and scream, ‘because that’s freedom’. I don’t think she’s heard of Femmen.

Now the guests are having a French themed dinner party. Vive La Revolution. Continual monuments, French revolutions/restorations/100 Days/republics 1789 – WW2; or constantly becoming, permanent crisis. We are constantly becoming. We make and remake each other over and over again, but don’t seem to know how to remake ourselves outside of capital, outside of its spectacle, outside of the trails of monuments that act like fractals and define our very existence.

That’s your life. I’m editing it, remotely.

3:

2009 was the end of everything that came before it. Bishop’s Artificial Hells before it was written. Participation played out as a cultural-governmental frame. Democracy Now (quick screenshot it!). We pick and choose our monuments, but sometimes they just fall to us. We find solace in the hopes and memories that we whimsically objectify. How we make material these moments is not through our technologies. They are just some of the tools, our hammer and sickle, our means of identification. We feature our preferred, select choice of identity, scanned through the checkout as we communicate with each other – our profile pictures, our pictures of each other on our phones, the way I know exactly what you look like when you ring me. Understanding any form of protest outside of these identifications seems like another apparatus of fantasy: a 4th plinth monument to memory. Consensus politics should be over, from the level of the imaginary upwards. Like we try to organise our pixels, we organise each other, we experiment in resistance. We are concise fibres within this grey but we can design and publish the memories that we aren’t, so it’s ok.

We consume memory – this historicised, spectacularised protest – as an object. These objects are ephemeral; not simulacral, not unusual, not representative of reality. They are, reality. Our imagined memories are real. Just like we don’t ‘go to’ the internet as a separate space; it’s woven into the fabric of our lives. So every imagined snapchat is as it parades, a real snapchat, a shared memory. We live in the footsteps of ourselves, over identifying our existence, our hyper-specificity. Camatte identified this when he told us that, ‘in Marx's time the proletariat couldn't go as far as negating itself – in the sense that during the course of the revolution it had to set itself up as the dominant class: 1848, 1871, 1917. There was a definitive separation between the formal party and the historic party. Today the party can only be the historic party.’1 We are the historic party and we can’t negate ourselves, we are the vendors, the buyers, the products, the revolutionary subjects, the bodies of capital. We fucked up our love for each other, the only historic love.

These memories of protests are monuments of self. ‘To be in love with someone means believing that to be in someone else’s presence is the only means of being, completely, yourself.’2

4:

There’s an image of a pop star on the screen. It tells us that it wants to be in our memories, wltm3 a way to form these out of nothing. It tells us that cycling around the streets and their contentlessness is nothing. The poster takes this image, makes it reality (artificiality is reality, the closest possible war is the one we see). If this poster in its representation is a form of organisation from nothingness, then that is the reality of neoliberalism: re-presentation, re-represention, #nodads because we no longer want to live in this. The banks said we can only take out €100 anyway but that’s ok. On street view I found the shop where you can get quavers for less than 50p.

2010: all the strength felt in protest worldwide disappears as soon as it appears, as soon as it didn’t happen, there is no concrete monument or poetry to say otherwise. Just as a wave of protest can dispel as soon as it speaks its name, trending and passing in a twitter feed, via its automatic recuperation by capital, or perhaps the inescapability of the two being one and the same thing, from and in the same site. The love that can only speak its name. A protest’s posters are propositions for memorials. They are gestures for a vocabulary of remembering, of our language, collectivised.

The poster is still an object even if its material references ban it from monumentalism.

We want to destroy all the ridiculous monuments to ‘those who have died for the fatherland’ that stare down at us in every village, and in their place erect monuments to the deserters. The monuments to the deserters will represent also those who died in the war because every one of them died cursing the war and envying the happiness of the deserter. Resistance is born of desertion.4

Let’s synapse this ephemera, maybe it’ll be us again, or as proposed in Time for Revolution: if we plug into past revolutions, we can reignite them for now. I don’t believe this fully. I guess all I believe is we are in communication, we can have the discussions we yearn to have, obviously, surely. Really posters are just methods of distributing our communication with one another, our voices when we say ‘I’m mad and I’m not going to take it any more!’ And maybe that’s what it is, that 2013 is the year of remembrance (remembrance to reignite the present). Remembrance of how shit it is right now. Dissemination itself as a memorial.

Hey, I can’t believe how close ‘posters’ is to ‘protest’. The potential for it always, but never.

5:

You watch me make images of us.

I think I’ve come to realise that the only way for things to be different is if I make them that way, completely in all aspects of me. Not as a realisation that follows any sort of profound reflection, just that sort of dull understanding that precludes something. What I mean is this is the beginning not the end. It’s the inverse of positivism. We talk about desire all the time without describing what it is. Or isn’t. I guess I can’t help but think as I write this, where are you now?

Silvia Federici disputes that we can organise from nothingness. She describes naming as a way to transcend, how denouncement comes from a process of making visible in order to then produce a common terrain on which to struggle. But if we look at our own lives, we see that any identification is lubrication for our subsumption. How can we racketeer against ourselves? Are we really our own worst enemies? Probably, yes; whatever situation we find ourselves in is already the situation of the oppressed. What if I emailed someone in my contacts list saying I feel awful, perverting our sociomateriality. Intervention on the base structural emergency of becoming: forever. I need you to say it to me, for us to become us, I want things to be different. Let’s militarise how we feel for each other, and by militarise I mean forever. Our nothing is point zero: in other words, right now.

If we map ourselves as memories (both real and imagined) then our protest, our desire for revolution, our desire to touch fingers, are one and the same thing. They are a stubborn decisiveness for rupture. I remember having to buy non-latex condoms in an old Boots right by where I lived once. Like the continual forming of nation-states, or the monuments of love constructed out of immaterial memories by ‘immaterial’ workers, then lived – if only because they were thought. We realise maybe the moment of rupture doesn’t come. Or it is just perverse moments of potential rupture. The knowledge that something might just snap, and the future memory of this being so. If we chose to live out, to ride out, the lapping of almost rupture we’d form memories together of it generating. We are hoping that diluted image of rupture, as a big bang and sublime bliss of our otherness as hedonism – the projection on Rihanna’s body as she comes up on drugs – isn’t the object we desire as our collective memory after all.

You’ve self-alienated yourself from me, as a sad, slow playing out of the endemic self-alienating tendencies of socially mediated capitalism, but also as a declaration that that is anyway what you want. Imagine coming with no gravity. Selfie. Space Fuck.

6:

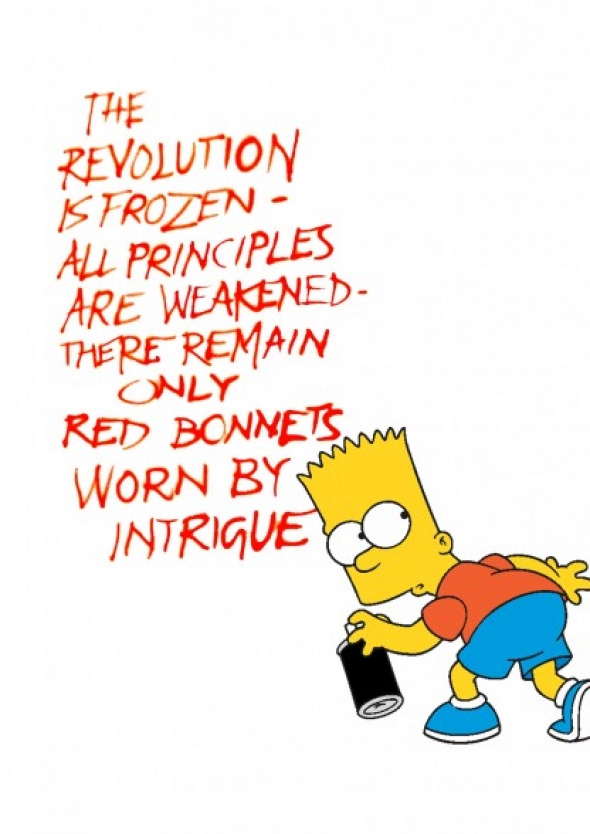

2013: we went to Charlie Woolley’s show at different times at first and then I was lying on the floor when you walked in. You recoiled when I touched your head, I almost think it was disgust on your face, well it was actually, not almost. We were so far apart, I’d self-alienated and your revenge was palpable. You leaving. Us sitting apart amongst those memorials, that assert their aesthetic language, the almost becomings of various revolutions that should have been. Just to draw upon, draw out a memory we want to have. It’s these appropriations that seep into collective memory, and allow for fictions to become assumptions. Capitalism, conservatism, liberalism, my childhood. Clause 4-less Blair ’97. I don’t think we’re immune. Taylor Swift’s video ‘I Knew You Were Trouble’ is reminiscent of a Rihanna ‘We Found Love’ and Lana Del Rey ‘Ride’ mashup. All telling imagined narratives of their bodies colliding into some man, that are woven with specific fictionalised moments in time and place of our collective memory. ‘I believe in the country America used to be’, purrs Lana Del Rey. Sociomateriality in action on YouTube, or rather in Vevo on YouTube. Their bodies are objects, our apparently desired memories making up their forms, easily mutable into whatever nostalgic tableaux are culturally appropriate at any given time. The pinnacle of this body-memory is mute.

Taylor Swift says: ‘I think when its all over it just comes back in flashes you know, it’s like a kaleidoscope of memories, but it just all comes back.’

Lana Del Rey says: ‘My memories of them are the only thing that sustained me.’

Rihanna (in an English accent, because we all know that, really, Rihanna is voiceless, that she can’t speak): ‘It’s like you’re screaming, and no-one can hear.’

Or Rihanna is, as Lana Del Rey describes, the other woman, who belonged to no-one, who belongs to everyone. Rihanna writes ‘yours’ in a sparkler, the beautiful male in the video tattoos ‘mine’ on her arse. My rant is scathing for a commons with no name.

How can we find a space within this to commonise? Perhaps we are self-perpetuating in desperation to ground everything out, to render it only pixels, to find the point/ground zero from which to organise (Bunny into Chavez)? I’m thinking about Jesse Darling’s piece There's A Little Pre-911 Myspace In All of Us (2012). What will the memorial be? As autonomism whimpered into individualism, our rendering, us drawn as a blank, happens as prolifically by individuals themselves as it is done by structural narrative, memory, adjustment, we. Let’s not let it happen. Bunny Rogers’ twitter feed regurgitates every facebook status update she writes, rendering her twitter an object-memory: an archive. Sister Unn’s by Rogers and Filip Olszewski was another object-memory. We produce our own script, and it is from a pre-produced narrative. Go to the rose gallery, go again it will spit it back at you, find your rose. How many flowers, how many unique visits, till the site would crash and we would see the code? http://www.sister-unns.com/. War is the memorial of the protest that never came.

All I know when we talk of our memory for each other, our memory that we live, is that we live it, that it’s embodied in collective performance. There is no binary, we are not Cartesian. We’re hot messes for each other, our insides falling everywhere.

Camatte said collectivising, identifying each other, becoming together – or perhaps simply locating the terrain for struggle – is only performing an existing capitalist motion of organisation. Data ebbs and flows through how we syphon the self through capital, feet not touching the ground, or each other: high frequency fading. But maybe also that’s why we form, file and flirt with these memories, these realities. Allowing our own conflict to be the very fragrance of its production, taking each other’s clothes off and wearing them backwards. Proposing in the park to each other. Living together, always.

All practices are always and everywhere material, and this is the materiality constitutive of the contours and possibilities of everyday organising. Nothing left but to make these memories matter.

This text was produced in a google doc shared between Rózsa Farkas and Harry Burke, March 2013.

Rozsa Farkas <rozsaATarcadiamissa.com> is director and co-curator/editor of Arcadia Missa. She has also written for Nottingham Contemporary, Mute, Jotta, Eros and others.

Harry Burke <info AT harryburke.tv> is a poet, writer and curator. He has written for Arcadia Missa, Rhizome, Clinic and has curated an exhibition coming up at Library +

Footnotes

1 Jacques Camatte, On Organisation, 1972.

2 Chris Kraus.

3 Would Like To Meet

4 Antifascist partisan, Venice, 1943, quoted in Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Empire, Harvard University Press, 2001.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com