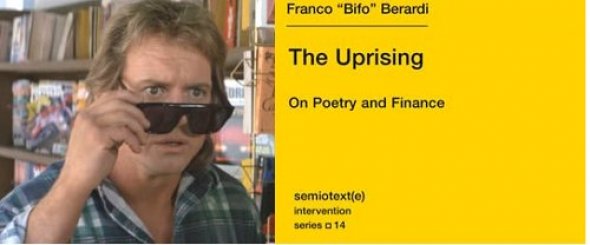

Poetry as a pair of sunglasses

Robert Kiely reviews Franco 'Bifo' Berardi's The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance

In John Carpenter's They Live (1988), Nada puts on a pair of sunglasses, and suddenly sees. He sees that many with authority and wealth are actually humanoid aliens with grotesque skull-like faces. He confronts an alien woman in a store and she notifies her associates. Some alien police officers apprehend Nada but he kills them, takes their guns, and goes on a zombie-alien-shooting-spree. It seems that Nada’s class consciousness is fully-formed as soon as the sunglasses reveal reality to him; minutes after ascertaining that his fellow species, i.e. proletarians, are being used vampirically by intergalactic zombie capitalist aliens, he is shooting them down in a bank. Almost too swiftly, insight is accompanied by action.

For Sean Bonney, the poetic image can be a counterpanoptic which ‘gives an x-ray view into the infraviolence of capitalist reality. He suggests that when ‘Lautréamont sneers that his pen has made a boring Paris street like Rue Vivienne “mysterious” he means the poetic image has been transformed into a splinter of glass fixed into the centre of your eye, a glass through which we see the capitalist class as the lice and bedbugs they really are, and in like fashion, the proletariat become a swarm of red carnivorous ants.’ Poetry might function, at times, as a novum, a pair of sunglasses.

Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi's The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance clarions that poetry, ‘the language of nonexchangeability’, will enable us to ‘see and create a new human condition. If the protests now stirring about the world are to take shape and direction, Berardi says, then the revolution will be neither peaceful nor violent – it will be linguistic, or will not be at all. Bold words. But if there is a single thing which will bring this revolution Berardi speaks of (and I sincerely doubt being this reductive helps), poetry is not the horse many people would bet on.

Which begs the question: what kind of poetry will hasten, or be, his revolution? Will more Carol Ann Duffy poems save us, in Bifo’s eyes? Through immiseration, maybe. The thing is, Berardi does not discuss a single living poet, much less a living poet who is also an activist. We get a bit of Yeats and a bit of Rilke – safe and dead. Revolutionary poetry is being written, and has been written for some time. The fact that Berardi quotes long-dead examples shows he is dimly aware of this. Ergo, Bifo’s cure – which I would suggest is linguistically and conceptually innovative poetry – is all around us. Berardi never considers this or the issues it raises. Perhaps this poetry, then, has already done its job and brought the revolution forward by a spring or two. Perhaps, also, the problem is that it should have a wider readership. Perhaps... no, no more...

Bifo spends a large amount of time examining our current hyper-quandary – it is a crisis of the imagination, of attention, of machinisation – but very little time on the book’s central thesis. Along the way, Berardi denounces violence and the London riots – for a ‘68er (and he likes to remind us he was there) this is particularly amusing. Do as I say, not as I did, bleats yesterday’s young Turk. He also seems to be heteronormative and rather technophobic: he bemoans the fact that babies are learning more words from machines now than from their mothers!

A caveat offered to the General Intellect: Baudrillard, Wiener, Deleuze and Guattari are The Uprising’s luminaries. I haven’t read them, they’re on my desk reproaching me. All of this is written in the spirit of improvisation.

I have sprinkled some scorn on Bifo’s suggestion that poetry will bring about change, and his manner of delivery. That shouldn’t detract from the importance of his suggestion, which is not simply to be jettisoned. It is possible that the most political poetry is that which revels in its own inadequacies, in the sheer nihilism of the possibility that poetry might change nothing. Ironically, poetry that grinds our nose in our complicity, and in its own complicity, may have the most potential to bring about change. The keyword here is potential – insight does not always draw behind it the plough of praxis. It is not always a beast of burden, sometimes it is wild, glimpsed in hedges, rummaging in our garbage. They Live is pure fantasy in this regard. Bifo seems half-aware of this too: the book ends with a discussion of cynicism and ideology, dissociation between knowledge and action, and ends up calling for irony as some kind of way out of this problem. The whole thing feels like watching a man pick himself up by his feet to throw himself across a river. It is worthwhile to stop and watch the contortions this presents us for a while. But those of us who take the questions which have motivated Bifo’s book seriously will have to look elsewhere to find a bridge, or start building one ourselves.

Robert Kiely hasn’t worn sunglasses in a while, but wears reaction-lenses because of some deal in Specsavers. His poetry and prose has appeared or is forthcoming in cancan, Scree, VLAK, and elsewhere.

Info

Franco 'Bifo' Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, MIT / Semiotext(e) / Intervention Series, 2012.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com