Putting Illegality to Work

The vulnerability of illegalised workers forces them to accept the worst pay and conditions and produces conflict within the working class as a whole. Here Seemab Gul examines how the production of this illegality is the main goal of the UK’s immigration laws

Under the guise of humanitarian work, established inter-governmental agencies like the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and International Labour Organization (ILO) handle the enforcement of neoliberal migration management. While the IOM takes pride in being the world’s largest ‘human-trafficker’, having moved more than 11 million people, the ILO is responsible for a ‘brain-drain’ of educated people from poor countries. Western governments recognise that immigrants are an additional resource for the economy since they meet the demand for cheap labour. If the demand for labour falls or their numbers exceed the demand, the immigrant workers become a burden to the state. They are then imprisoned in camps or detention centres or forcibly deported. While governments may try to maintain this situation, many undocumented migrants remain illegal to avoid the harsh detention and deportation regime.

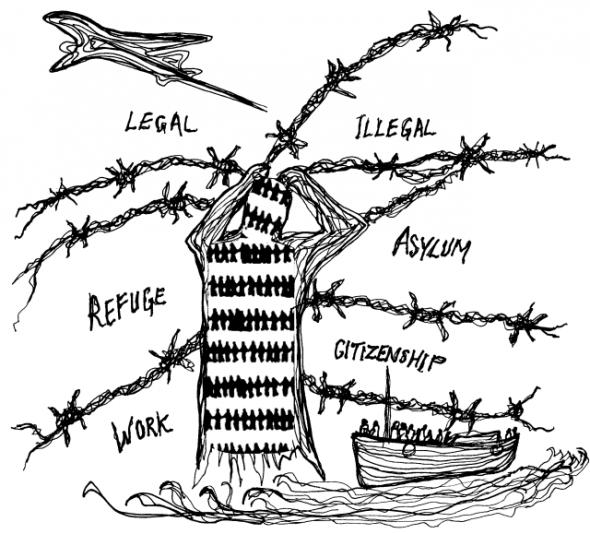

In the UK, the official estimate for the number of ‘illegal’ immigrants is half a million. Many have endured a long and dangerous journey into the country. Once they are here, they end up in precarious working conditions and face increasingly strict migration laws. For many economic migrants, the options on entering Britain are limited, especially if they have entered illegally. Since asylum is not open to economic migrants, they become ‘illegal’ at the time of arrival without having committed any other ‘crime’. However, in practical terms the distinction between legal and illegal becomes blurred as they join the legal low-waged workers in the UK. For these people there is little chance of eventually becoming legal since their existence is not recognised within the current legal framework.

It should be noted that the Labour government was recently challenged for underestimating the number of immigrants to Britain since 1997, and had to admit that most new jobs created since then went to immigrants. This admission comes at a time when economic needs are becoming a legitimate pretext for migration, to the detriment of asylum based migration for which the quota is being lowered. New Labour has proposed a new Points-Based System that will bar all but the most skilled non-EU workers [see p.42 of this issue]. A new Citizenship and Immigration Bill will set out a foreigner’s duty to learn English and sign up to British values before coming into the country. Economic migration attaches conditionality to residency in new ways, with the Points-Based System further instrumentalising the role of the migrant.

The atmosphere of fear and paranoia cultivated by the state since the 9/11 and 7/7 bombings has resulted in the creation of more stringent anti-immigration laws. Recent measures involve proposals for a £1.2 billion electronic-border project and the creation of a new border agency uniting Customs and the existing Border and Immigration Service. The British government has taken steps to speed up the asylum application process resulting in an increased annual number of deportations. Asylum seekers are treated like criminals with dehumanising schemes such as electronic tagging and a voucher system trialled on them. The system by which asylum seekers bid for legal refugee status resembles a lottery, with government quotas overriding the reality of applicants’ actual needs or survival chances.

Asylum seekers from war-torn countries like Sudan, Afghanistan and Iraq are sent back because these countries are considered ‘safe’ by a British government with deportation requirements to meet. This often comes after risking life and sacrificing savings to gain entry to the country, while the rich have student and tourist visas, ‘business’ options and comfortable flights available to them. Britain harnesses and safeguards rich and corrupt politicians from around the world under the pretence of ‘asylum’ while deporting thousands of others whose lives are seriously endangered.

For some, the decision to stay underground is not a choice but a strategy to survive the harsh climate of exclusion and fear. A legitimate application requires the asylum seeker to prove the threat they face in their country, defining them as ‘guilty until proven innocent’. If the starting point is one of ‘guilt’ and criminality, then it can become imperative to continue this path of ‘illegality’. While asylum seekers can also be economic migrants, economic migrants cannot seek asylum since ‘starving’ is not considered a legitimate reason for asylum. Refugees are treated as ‘unfortunate, needy and honest’ victims, while failed asylum seekers and economic migrants are considered liars and parasites. The Labour government insists that all ‘illegals’ should be deported regardless of the dangers they face in their countries of origin, but claims that it may take more than ten years to deport all ‘illegals’ and failed asylum seekers from the UK. The actual situation seems to be out of the government’s control and is in practice regulated by the needs of the economy.

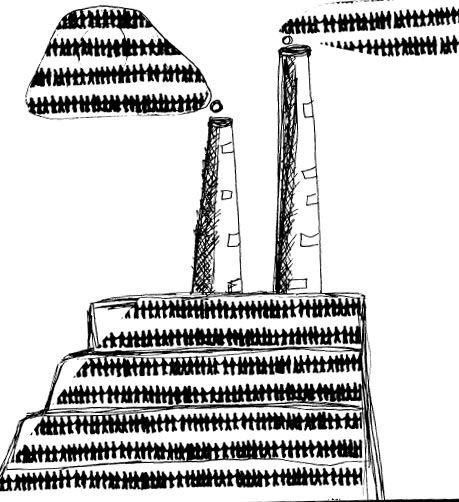

Western capitalists relocate across national boundaries and move their factories to any developing region where they can avoid taxes and exploit workers for larger profit margins. Britain, meanwhile, is slowly becoming a nation of administrators, as manual labour is increasingly undertaken by migrants. The existing working class are not only struggling for jobs and housing, but also end up having to compete with the new workers coming into their areas. Due to social and economic divisions, if it is not racism then it is competition that isolates the immigrants, causing further tensions.

Image: Seemab Gul, Human Factory, 2007

The racist and xenophobic press has hyped the numbers of the East-European workers coming to the UK and fulminated against failed asylum seekers who protest in detention centres. The image of the ‘good immigrant’, i.e. hard working and law-abiding, promoted through state and mainstream media idealises middle-class immigrants. This is wielded against the majority of migrants in the UK with the intention of coercing them into the discipline of work. Despite the government’s efforts to classify and tier immigrants on an individualised level, thus weakening solidarity between individuals and groups, the media stubbornly projects all immigrants as one big problem.

The influx of legal migrants from the new EU states is proof that there is a demand for low-waged workers in the UK. This demand by employers undermines the decades of struggle by British workers who have fought for the minimum wage, holiday pay and pensions. This threat is used as a stick for legal workers to stay in line or lose out to new workers. Most new immigrants work willingly in the worst conditions and on the lowest pay because they have come a long way in search of work and survival and live in constant fear of deportation or detention. Consequently it is difficult for immigrants to demand better working conditions or to organise in the workplace, further deepening divisions between British workers and new immigrants.

To counter the ageing population in the UK and low birth rate, the liberals and the government are in agreement that there is a need for a young work force. They suggest that immigrants can and should be ‘imported’ to fill these gaps in the labour market. Similarly, the market demand for sex and drugs enables these industries to thrive regardless of their legal status. The desperate and ‘illegal’ immigrants have few options available to them but black market work.

M. Ricciardi and F. Raimondi have argued that

the point of view which aims to recognise the economic necessity of migrants to contemporary social production, ultimately considers only the needs of those who offer employment and the means to satisfy these needs.[1]

Although recent migration, especially from the EU, is presenting new challenges, different ethnic groups are systematically separated, favouring those who are able to integrate well. As a result of the ‘war on terror’ Muslims are targeted as problem cases with more stringent visa restrictions than white Christian Eastern Europeans. The assumption that all non-Europeans must belong to a community, religion, culture or ethnicity is also an attempt to define and control immigrant populations – an attempt that underlies the integration debate. Integration may make the lives of many immigrants more tolerable but it cannot take place as long as they are ostracised as the lowest wage earners in the labour market. The integration debate is irrelevant as long as work places are divided between different ‘community’ groups fighting for jobs, housing and wages, with illegal workers at the bottom of the heap.

While the trade unions are losing negotiating power within the legal framework, even the legal workers are finding it hard to make demands. Ricciardi & Raimondi believe that:

migrant labour today is a condition that anticipates and shares the general conditions under which contemporary labour as a whole is distributed.[2]

Nevertheless, legal status has its benefits such as access to medical care and, in theory, housing and a greater possibility of finding work. The undocumented immigrant may aspire to civil, political and social legality, if only in the hope of improving her prospects and working conditions. Most would take up ‘regularisation’ or amnesty if it were offered to them in order to avoid total insecurity, the constant threat of deportation and lack of medical care. However, while hundreds of thousands may apply for amnesty in the hope of becoming legal, only a limited number will get it and then only if they fit particular criteria. The rest will be caught in a government trap having made themselves ‘visible’ and would face detention and deportation. Those who work in the black market might not bother with amnesty or any other legal route because they risk their livelihoods in the process.

For those who have already been detained and deported, the risks outweigh the benefits of becoming ‘legal’. They have felt the violence and the bureaucracy of the state first hand, all too similar to their dealings with human traffickers. They are aware of tedious ‘legal’ battles with the assistance of often corrupt lawyers who try to con them out of money. The struggle to become legal almost mirrors the struggle to survive illegally. It thus becomes far easier to avoid the legal route altogether out of fear of state harassment, constant abuse and long detention before deportation.

In order to regulate the labour market, immigration regimes and border controls create ‘illegals’, producing their vulnerable condition once inside state borders. Making the benefits system out of bounds for undocumented migrants is therefore a safe option for the government, one that cheapens labour whilst protecting national resources. Whether the government acknowledges it or not, ‘illegal immigrants’ are the invisible work force within Britain. The idea of a one-off ‘regularisation’ or amnesty will only make a limited number of illegals into documented, regulated, taxed yet low-cost workers. While the UK government is attempting to deal with the issue of migration through a possible amnesty, borders will be sealed more tightly against future migrants until there is a gap in the market that needs to be filled again.

Seemab Gul <sab76 AT mail.com> works at Mute magazine and supports London No Borders. Her multi-media works span themes of migration, identity, culture and politics

Footnotes:

[1] M. Ricciardi and F. Raimondi , ‘Workshop IV: Migrant Labour’, in Reader for the Europe(an) Wide Preparation-Meeting of Groups, Networks and Initiatives Working on Migration – produced for the Migrant Labour conference, held at Queen Mary College, London, 2004.

[2] Ibid.

Links:

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com