Forensis Is Forensics Where There Is No Law

During Forensis, an exhibition and conference at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin this Spring, researcher-curators Eyal Weizman and Anselm Franke talked to Gal Kirn and Niloufar Tajeri about the relationship of forensics to emancipatory politics and the aesthetic implications of ‘forensic realism’

Niloufar Tajeri (NT): You have been collaborating for a considerable amount of time now, could you tell us a bit more about your collaboration, and how that led to the concept of ‘Forensis’ in the framework of the exhibition at the HKW? What was the main curatorial concept of the exhibition, and how did you relate to the particular context of HKW?

Anselm Franke (AF): In 2003, I co-curated an exhibition with Eyal, his collaborators, and others, based mainly on his early work, the Politics of Verticality and A Civilian Occupation. It originated at Kunst-Werke in Berlin but became a traveling exhibition. Broadly speaking, Eyal’s works then expanded given trajectories of architectural research and spatial analysis in groundbreaking ways. And as they interrogated in great detail the specific situation of the occupation in the West Bank through an expanded notion of architecture and political space, entangled with the frontier-geographies of war, they also opened up larger horizons of historical reflection on modernity. The exhibition Territories attempted to articulate this double movement: with the historical work of architects and researchers Sharon Rotbard and Zvi Efrat span eight decades of architecture in Israel and occupied Palestine, but it also related this history to the rise of the security paradigm – and the emerging geographies of extra-terrritoriality in the War on Terror – and to deep-seated genealogies, narratives and implicit scripts concerning the nature of power, order, frontiers, the political imaginary and space in modernity.1

In our different ways, and within different yet overlapping disciplines, we have both continued these investigations ever since. My role in Territories as well as in Forensis is primarily curatorial, both in the sense of scenography and narrative. It is important to state that both exhibitions are indebted to a long history of architectural and research-based exhibitions in critical geography and design, and to a younger tradition of research in the arts. My work focuses on translation of research and various genres of narratives into the medium of an exhibition.

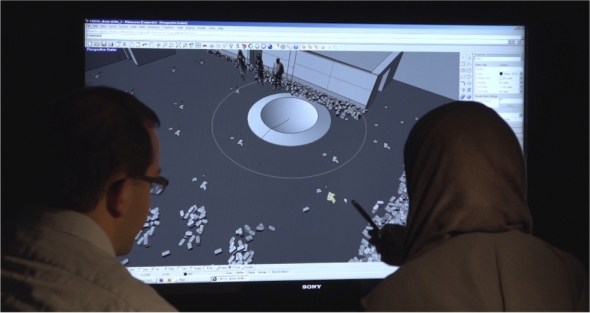

Image: Exhibition view, HKW, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

The curatorial concept for Forensis is clearly indebted to Territories. It is a logical expansion of its premises, where the tools of analysis, next to the subject of the investigation, assume an important role. Forensis is more like the sketch for a methodology, not only of research, but of the role of research in political action under transforming frameworks. And although explicitly related to the Anthropocene Project at HKW, the curatorial concept has been based on the collective work in the research project Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths. The task was to translate this work into an exhibition, which would explore different registers of the kind of ‘forensics’ proposed here, and give the vast range of materials a sort of systematic shape. In this, it followed, but also diverged from the parallel work done on the excellent publication under the same title.2

NT: I was wondering if the exhibition in KW in 2003 that dealt with territories and geography doesn’t open a certain associative path to the discipline of archaeology that we can locate in the exhibition ‘Forensis’, and particularly in the concept of Forensic Architecture. In one of your texts, Eyal, you referred to Forensic Architecture as ‘an archaeology of the present‚ unpacking present histories in order to critically engage with the dynamics of political events as they are unfolding, in contradiction to archaeological obsession with the past’.3 In the HKW it seems that the exhibition itself, how it was designed and how the contents and the projects were put on display, it strongly reflected the idea of the ‘archaeology of the present’. Was this the guiding concept you were pursuing regarding the exhibition design?

Eyal Weizman (EW): Our insistence on forensis rather than forensics is meant to engage with the present, with current political processes – not with a dead body under the microscope but rather a living one twisting under pain – this requires political understanding and political intervention. All our investigations involve ongoing conflicts, not issues of transitional justice. And in on going conflict analysis is part of the logic of the conflict. The theme of archaeology was already present with the Territories exhibition. Forensis comes almost ten years after Territories – which foregrounded the architecture of Israel’s occupation as an example of slow architectural violence. Hollow Land, the main piece in Territories was a detailed investigation of a panorama taken from exactly where Mark Twain stood in the 19th century – now looking towards contemporary Bethlehem. We printed it (it was an image by Daniel Bauer) as a 60 metre long and 6 metre high single panorama.4 We then started reading all details this image together, some large landscape features and details hiding in the pixels, in the blurs, at the limit of vision. I think this collaboration between a curatorial perspective and that of architectural analysis put into motion the kind of forensic/archaeological aesthetics already distinct in the Territories exhibition.

We have learned to look together for the ways in which historical, political forces are slowing into form – of buildings and landscapes. If it is an archaeology – its subject matter keeps on moving and transforming – there is no static state in material transformation, just as there is no neutral perspective. Even a fossil – made by the weather, environment, minerals, rock type and organism took millennia to form but still undergoes transformations at present. Likewise Architecture is violence is slow motion but still transforming. its snapshots of reality are captured not in celluloid but in concerete and clad in stone. Aesthetics is at the centre of our approach in different ways – in the sense of how politics appears to us, and how we make claims with its representation, but also in the meaning of the aesthetics of matter – aesthetics is the meaning of a sensing, of a sensor. The aesthetics of architecture is how its material components react – that is how they sense politics – registers politics as if it was a sensor.

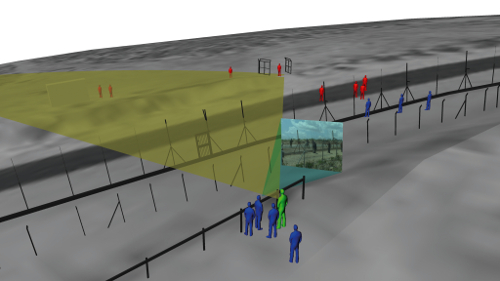

Image: 3D-Rekonstruktion of the moment when a Palestinian protestor was shot by Israeli military.

Gal Kirn(GK): Anselm, we were wondering, if and how there is a connection between Forensis and your concept of Animism. At least at first glance it seems that one of the central operations is analogous, namely, in stressing and understanding the ways which objects can be made to speak and move. Could we argue that one of the central methodologies of forensic animism deploys and makes material, matter and built environment speak, animate and reconstruct for the purpose of investigation? Where would you draw main similarities and differences?

AF: Yes, we could call that a central methodology, one out of several. Especially in a sense where the ‘speech’ of objects is tied to different epistemologies and even ontologies. But perhaps one should not try to stress the common concerns too much, I'd rather draw a sharp distinction: because ‘animism’ dealt above all with the ontological intolerance and warfare of modernity and the role therein of the dialectics of subjectification and objectification. And it dealt with what we once called, after Sergei Eisenstein, the modern ‘trouble with the anima’, with the soul, with subject-formation and embodied cognition. Or, in other words, with the design and engineering of the psyche in a secular modernity that cannot rid itself of its religious and colonial bias. Animism as a project is primarily concerned with the boundary-making practices of modern institutions, and the symptoms that these practices yield in the realm of modern media at large. Symptomatic readings like these (holding up a dialectic mirror), however, do not serve the kind of purpose that ‘forensis’ looks at and seeks out. But there are single moments in the Forensis project, too, where such readings of aesthetics as symptomatic are at the fore, when it comes to the credibility of the forensic performance in the service of the state, to mass entertainment in TV, and so forth. But in court any such argument related to symptoms and aesthetics wouldn't get you anywhere, or at worst, it could get you into the extremely dangerous zone at the nexus of the state and pathology.

But what both projects might share beyond that, actually, is a questioning of the concept of a sociality and even polity that is expanded to include non-human nature. One of the blind spots of this discourse is: how should the ‘parliament of things’ that is being called for by Bruno Latour and his disciples, actually look like? Well-meaning ecological metaphor doesn’t make good politics in a field defined by interests and ideology. The concept of the parliament of things forgets to theorise that which is most political about the parliament: namely how it is being policed, how the seats are distributed and what counts as legitimate speech in the first place. The ‘forum’ of Forensis is a related, but different proposal for how things come to enter into politics.

EW: I understand Gal's question in a very straightforward way and would say that on one level it is true that the conceptualisation of Forensis began in relation to ideas that were developed in the Animism exhibition. Of course saying that objects speak would be a short cut, but the borders between subjects and objects do blur in this exhibition. In the context of forensics pathologists sometimes speak about bones – objects – as if they were subjects. If, in the legal perspective testimony, people and evidence – things – are kept apart very rigidly, the exhibition shows how they start being not so clearly separable. Forensis demands for transformations both on the level of the subject and that of the object. It is produced through an entanglement of technologies, articulation of objects, materials and human memory. Articulation of truths is composed of things, technologies of detection and technologies of presentation. When any border erodes – like this between subject and object – both sides of it are also transformed.

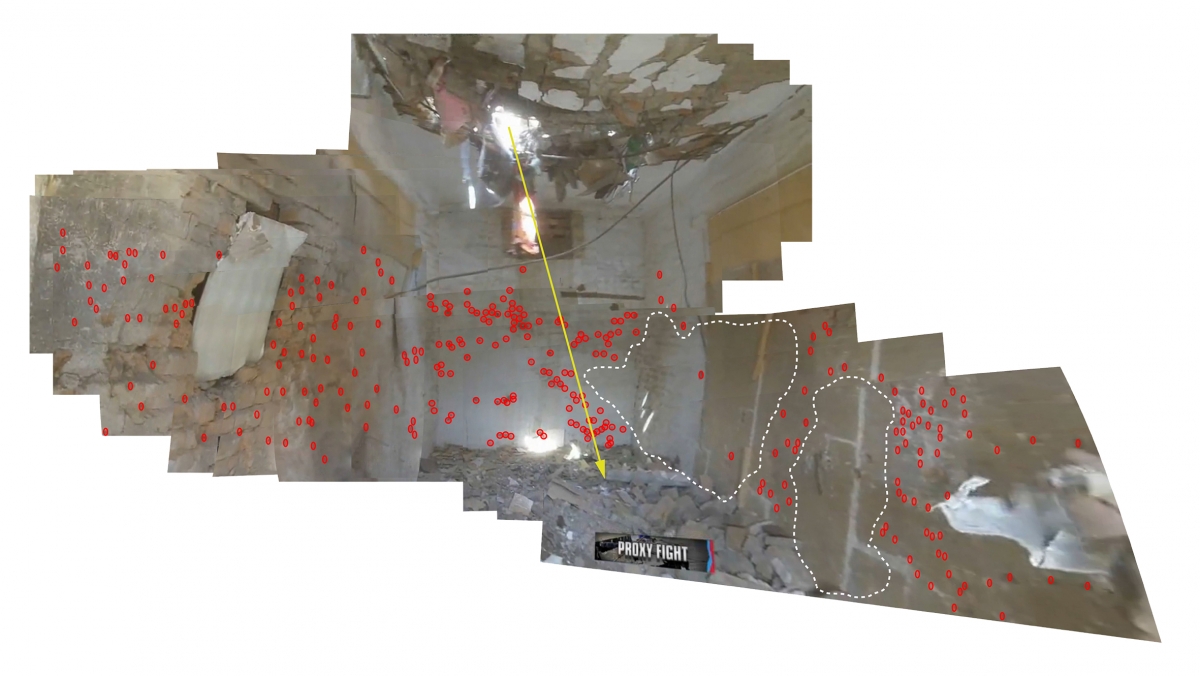

Image: A photograph showing the drone bomb’s path through the Salha family home is here overlaid on the model Forensic Architecture reconstructed with the help of Noor and Fayez Salha. The model was used as a tool to help the survivors recount the night of the strike in Gaza.

GK: So, one of the important trajectories of Forensis is a different reconstruction of the history of violence, where the borders between subject and object are redefined in the process, where, I would agree, one can find certain anti-statist core in the formation of the forum. This brings us to another question and additional comment: the question of making a different kind of history, which is not done by law or politics, but is mostly organised through architectural and aesthetic means, to what Eyal referred in the very beginning. I am interested in which ways aesthetics is used, touching on the relationship between forensic, modernism, and realism. I could very well see a certain similarity with the history of early cinema and its mission: it was believed that early cinema cannot only register and represent reality as it really is, but also – in a modernist way – construct the world and create a reality as it ought to be, as cinema-truth. This approach runs from Matuszewski to Dziga Vertov and after. Can we, in the case of your project, speak of a certain forensic realism, a tendency to represent reality in the way it really is, or is there rather something of what ‘ought to be’, which is constituted via the forum and its alternative conceptualisation?

AF: You could definitely draw a connection to this moment of calling upon what ‘ought to be’. There are several contributions in the exhibition that call for forums that do not yet exist. But there is no underlying ‘theory of justice’ expanded to a forensic aesthetics here. I would call it systemic or structural realism, in the sense that it is realism only insofar as that it modulates the speech of objects or imagery such that their ‘speech’ can be comprehended. And this amounts sometimes to a ‘negative realism’, mostly in the face of forensic technologies and their use by the state. Such negative realism lucidly invokes how structural and systemic parameters produce reality, and ‘truth’. For example, think of the investigation of the use of forensics of the voice in migration by Lawrence Abu Hamdan.

NT: I would like to discuss further around the question regarding forensic realism and how something in a specific context performs in a way that suddenly becomes ‘real’, even in a very rigid place like a criminal court. When we take for example the particular case study of Forensic Architecture on drone strikes in Mir Ali, North Waziristan. The witness reconstructs her memory of the house, which was destroyed by the drones. The testimony is visualised and constructed in front of our eyes. Indeed, what unfolds before our eyes is a ‘ghostly realism’. I found it striking that according to Michael Sfard this particular case would be valid as evidence in court, because the actual reconstruction of memory was documented on tape. Here, we witness how the forensic performance of a testimony turns it into hardcore evidence. However, there were also cases in the exhibition – thinking of Adrian Lahoud's work on climate change – which would not hold on court. So the exhibition shows very different notions of forensic realisms and confronts us with different legal implications. What brings these cases together in the context of the exhibition? Is it a kind of constructivism, a notion of universalism, or is it a certain relationship to science, which these very different cases have in common?

EW: The question of universality in this project is articulated not within the domain of an inter-state international, but in frontier zones – in lawless zones – where state violence now most often takes place. The zone between Pakistan and Afghanistan is an area where, because of its unique history since the time of the British Raj, managed to successfully fight for a high degree of autonomy from state sovereignty. So in a sense, Forensis is forensics where there is no law, beyond State law. When operating in these frontier zones we need to invert the forensic gaze. It’s not the state that surveys its subjects, citizens or non-citizens, but it is politically motivated organisations that return the gaze towards the state seeing it as a criminal organisation. But when citizens turn their optics on the state they also find themselves in situations of epistemological and visual inferiority. Evidence will always be at the threshold of visibility, or detectability, and at the margin of the law. And this is another frontier that Forensis had to investigate and surpass: the threshold of detectability. This refers to situations where violations are undertaken exactly at the margin of the unseen. Precisely because they are unseen, the traces of such crimes are smaller than the pixels of the images in which they are captured.

This is why all the evidence that we produced is not located very comfortably within the centre of what is accepted as evidence by legal bodies. What Forensis is trying to do is to push the boundary of what can be seen, said and qualify as truth, and what can be qualified as evidence. If we had better access, better tools, like the tools and access that states have, of course you would have a much safer evidentiary margins. But what we’re looking at are weak signals at the threshold of detectability. In several instances our cases were thrown out of court for the excuse that our technology has not yet been verified, that we being artists and architects (and our forensic agency is made by a group of artists and architects) our team does not have the right expertise. This shows, how forensis is at the threshold of science and at the threshold of the law. We see a ‘swoosh’ of pixels in the line – designating what we believe to be the flight path of a gas canister shot by soldiers at the chest of a demonstrator – but this is still denied by the army. Or, as in other projects, we tried to enhance the fragile memory of a survivor, but the computer reconstruction process could is also contested by court. In another case we are looking at the analysis of 22 seconds of video – 24 frames times 22 seconds – there are a lot of open questions.

Because our work exists at the threshold of science and the law, it could also be in excess of science and law. This kind of fragile evidence calls for political mobilisation, political commitment to gather around them. Truth is a common project under construction.

Forensis thus, in your terms, shifts between forensic realism and forensic surrealism. Because the more you subject your material to analysis the more you always will find moments that are in excess of science and scientific truth. The face of Josef Mengele appearing through his skull in a forensic investigation [image], or when a suspected Neolithic site all of a sudden appears under a WWII era concentration camp [image], or when things are asked to speak or not, and memory conjuring in ferocious details a certain reality. Images appearing in the dust.

NT: Taking these different thresholds into account, we were wondering about the prevailing aesthetic code of the exhibition. Very different topics like genocide, environmental destruction, and the question of linguistics are visualised according to a uniform visual language, using similar colours and diagrams, and collectively presented in lightboxes. One could speak of a distinct aesthetics of ‘Forensis’ which brings us back to the question of forensic realism. Is this an attempt to universalise these very different typologies and cases into a forensic condition?

AF: Yes, you could say it in that way. But the exhibition must of course above all assist in making a vast variety of materials legible without asking the viewer to comprehend a different logic for organising materials 30 times over. Because nobody does this in exhibitions, this belongs to the space of the book. And simply the fact that this was not a contemporary art or else a themed exhibition, on the ‘topic’ of forensics, but an exhibition that turned a 3-year research project including architects, artists and others, into an exhibition, made certain decisions on the display inevitable. The lightbox simply indicated which imagery we wanted to be looked as forensic material. The exhibition had to instruct and direct its viewers on how it employed the forensic gaze.

Such employment ideally leads to an exhibition reflecting the means it uses. An exhibition should always articulate its own conditions as fully as possible, and thus make them part of what is proposed, and what is being negotiated in the first place. The exhibition design attempted to reflect its dramaturgy, in which one of the underlying implicit consequences is that we recognise that under the conditions of the globally operating digitally enhanced maps that we navigate, we are at all times always already forensic objects.

GK: Apart from the critique of the state, there is another topic present, which we could trace as the critique of a more humanitarian, liberal NGO prism structuring the field of discourse nowadays (as in the book The Least of All Possible Evils) which criticises the state violence or other forms of violence. We were also wondering if the main task of Forensic Architecture is to unveil, or make visible both the military power, the war machine, and on the other side a critical knowledge of the dominant ideology? One can find a strong Foucauldian kernel within Forensic Architecture, which brings to the fore this link between power and knowledge, an axis in which the show participates itself. There is a call for political action, and at the same time with exhibitions and with the production of alternative knowledge, there is also the participation of what Foucault would analyse in an encounter of knowledge and power.

EW: You are probably right. From our position – somewhere stuck in the middle – we can simultaneously look backwards and forwards so to speak – at both the violence inflicted by the state and also at the way in which the NGOs are made complicit with it. Today of course all the organisations committed to minimising violence, such as the UN and a host of human rights groups, under certain circumstances they would end up colluding with state violence. Colin Powell said about these groups that they are ‘power multipliers’ for the US military. This double critique both at the crime and at the management of the crime so to speak and thus at our own potential complicity has been a central feature of our project from the very start. My first book in the context of this project, The Least of All Possible Evils, deals precisely with this condition and proposes ways to deal with it. It shows how when you work in a situation in which your horizon is not to confront state power but to moderate, to improve, to make it sweeter, you might become part of the way state power is organised. The project emerged from looking at the slippages between human rights organisations, humanitarian organisation and to a certain extent human rights and international humanitarian law – with the state machine. Although the book marks the horrible limits of this complicity – when human rights principle become means of controlling people in occupied territories – it also proposed that we can never be completely outside the political force field. In fact, one of the reasons for us to try to engage in political analysis is in order to understand the field and be able to minimise complicity with the state.

In whatever forum a piece of evidence ends up performing there is also always an excess of the juridical. Forensis is about opening multiple forums in which our material or media analysis could operate. Diffused fields of causality – and contemporary violence is never a straight line of fire or causality between a perpetrator and a victim – require a diffused form of political action. The lawyer and activist Michael Sfard mentions this in his contribution – an interview – for Forensis. In the legal case we worked together on in relation to the Wall in Palestine, this case in Battir a historical village next to Bethlehem, we didn’t want to enter into the logic I described as that of ‘the best of all possible walls’. In previous cases it was always human rights groups who improved the wall. What we did there in this case was to break away from human rights principles, and articulate the position on behalf of the environment. By shifting from human rights principles to environmental ones – by claiming for non-human actors like the earth and the multiple necessities – he was able to break the equation of security with human rights, with the results still open. For the first time in a legal action in Israel, neither the principle of a wall nor its improvement was accepted The claim was basically that in this landscape ‘a wall is not possible’. We are not at the end of this process but this is the case for this particular zone, for this kilometre and a half of wall. What is the difference between this particular strip and other locations along the wall, or the wall in general?

NT: In the case of Battir you mentioned in your presentation that it was actually the visualisation of the landscape, which basically convinced the court. And it is in this power of the visualisation that the discourse on manipulation pops up. For example think of how Colin Powell showed the fake 3D modelled view of what the laboratories in Iraq looked like before the United Nations and how this was actually a political tool to justify a war – and it worked. We were wondering how you address this manipulative dimension that is inherent in any kind of visualisation?

EW: I think one of the fundamental actions we can undertake is to describe the world. This description of the world is an aesthetic act.

AF: I would also say that with regards to the manipulation of imagery, everybody should know that by now, and nobody should naively believe in power point presentations of evidence. But to shout ‘manipulation!’ also doesn't lead us anywhere, as if there was a world without that possibility, one that wasn't sutured with ‘manipulation’. All that makes sense today is to actually train the eye.

EW: Training the eye has nowadays to do with understanding the nature of images, their materialities, their protocol of transmission, circulation and viewing, the spaces of its viewing – to see videos in the way that we need to see them in the context of forensis it to view them all the way down to the pixel it is to build models and locate them in space and it is to show them in different fora. Viewing is not a solitary action of a subject facing an image/object in front of her or him, but it is about a set of relations that are continuously transforming between the materials affected and a viewing public. To make something visible you need not only to come up with an image, but to try to transform political relations around what you show so you need the language, to speak about it. The apparatus of vision is much wider and more complex and involves a host of technologies, techniques, sensibilities and aesthetic moves.

Anselm Franke is a curator and writer based in Berlin. He is Head of Visual Arts and Film at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, and Chief Curator of the 10th Shanghai Biennale. In 2012, he curated the Taipei Biennial. His project *Animism* was presented in Antwerp, Bern, Vienna, Berlin, New York, Shenzhen, Seoul and Beirut in various collaborations from 2010 to 2014. He was the Artistic Director of Extra City Center for Contemporary Art in Antwerp and curator of KunstWerke.

Eyal Weizman is an architect and writer based in London. He is Professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures and Director of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London. Since 2014 he is a Global Scholar at Princeton University. He directs the European Research Council funded project *Forensic Architecture *since 2011. Weizman has been a Professor of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and has also taught at the Bartlett (UCL) in London.

Gal Kirn is a political scientist and writer based in Berlin. He received his PhD in political philosophy and is engaged in topics of (post)socialist transition at the Workers'-Punks' University in Ljubljana. Currently he holds a postdoctoral fellowship granted by the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation and researches on the history of media at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

Niloufar Tajeri is an architect based in Berlin. She teaches at the Chair of Architectural Design at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and is currently working on her dissertation at the Chair of Architectural Theory. She is a fellow in the architecture section of the Akademie Schloss Solitude, and has been working as an editor for the architecture magazines ARCH+ and Volume.

Info

The Forensis exhibition took place at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin, 15 March - 5 May as part of The Anthropocene Project, a two year program of exhibitions, events and publications held at HKW Berlin 2013-2014, http://www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2014/anthro...

Footnotes

1 The exhibition Territories took place in KW, 2003, 2.6.-7.9, http://www.kw-berlin.de/en/exhibitions/territories...

2 The Anthropocene Project is a two year program of exhibitions, events and publications held at HKW Berlin 2013-2014, http://www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2014/anthro...

3 Text by Eyal Weizman, Paolo Tavares, Susan Schuppli, Situ Studio, „Forensic Architecture“, published in Architectural Design.

4 The image is reproduced in ‘The Hollow Land’, Mute Vol.1 #27.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com