Falling for the Future

The computer inspired a wave of post-war 'imaginary futures', from ecstatic fantasies of time and space travel to fears of mankind's extinction. Iain Boal brings three critical histories of modernity's futuramas back down to earth

Digital utopianism has been awaiting its historian. The phenomenon is important, even central, to any adequate account of late modernity. When a strain of technological pessimism turned apocalyptic after the US defeat in Indochina and the capital crisis of the early ’70s, it was the personal computer that allowed the bourgeoisie to fall in love once again with the future.

But this development contains several historical puzzles. Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture begins with the intriguing question: how can one account for the remarkable transvaluation of the computer from a Cold War accessory to omnicide and ‘soul murder’ into a convivial tool of personal liberation, all within 30 years? Specifically, in Berkeley in 1964, ‘disembodiment – that is, the transformation of the self into data on an IBM card – marked the height of dehumanization’, while for the digital utopians of the 1990s, ‘it marked the route to new forms of equality and transformation.’

Rummaging through the history of the future has a kind of absurdist pleasure, and there is fun to be had condescending to antiquated predictions, to ‘yesterday’s tomorrows’ in the happy phrase of Joseph Corn, Smithsonian curator of techno-utopias past. Futures, however, are a serious business.

In the summer of 1997, towards the high noon of cyberhype, it is estimated that 20 million dollars of venture capital flowed into Silicon Valley every day, followed closely by half the entire graduating class of Harvard MBAs, who normally come to ‘everyone’s favorite city’ only for recreation. They were drawn to San Francisco by the Niagara of speculative finance, in the knowledge that rich pickings were to be had, for the price of a business plan on the back of a napkin containing the magic words ‘start-up’, ‘IPO’ and ‘stock options’, in any combination.

Image: Think Tank by Alex Veness. A college of the Beinecke Library at Yale University, New Haven (bellow) and one of Buckminster Fuller's goedesic domes (above)

Richard Barbrook, on the other side of the Atlantic and labouring in the virtual ateliers of old Europe, apparently felt the tug of the silicon force-field. ‘If we are talented workers in the “cutting-edge” industries like hypermedia and computing’, he wrote,

we are promised the possibility of becoming hip and rich entrepreneurs by the Californian ideologues. They want to recruit us as members of the ‘virtual class’ which seeks to dominate the hypermedia and computing industries.[1]

Barbrook’s labourist instincts must have been offended, because he responded on behalf of all the virtual craft workers of the continent. He composed The Digital Artisans Manifesto with Pit Schultz, which begins by announcing:

We are the digital artisans. We celebrate the Promethean power of our labour and imagination to shape the virtual world. By hacking, coding, designing and mixing, we build the wired future … We are the only subjects of history.

This matches any effusion from the Californian barkers of the virtual. The manifesto went on to conjure William Morris’s utopia of utility and beauty, upgraded for the new millennium:

in order to express ourselves directly by constructing useful and beautiful virtual artifacts … [w]e rejoice in the privilege of becoming digitial artisans … We are the pioneers of the modern.

It seems to be Nikolaus Pevsner’s proto-modernist Morris they had in mind. After talk of DIY culture and the gift economy of the Net, there’s a segue into a clarion call for a trade organisation of hypermedia and computer artisans, tasked with building the information society of the future

… We are not petit-bourgeois egotists … We proclaim that the collective expression of our trade will be: the European Digital Artisans Network (EDAN).

The manifesto is an honourable form. To jeer at the pronunciamentos of the past, not least cyber-manifestos dragged from the lumber room of history, is a one finger exercise, and it is not our purpose here. In any case, the hyperventilating prose of The Digital Artisans Manifesto is hardly distinguishable from a thousand similar fin de siècle productions coming from the hi-tech PR machines geared to Wall Street or the hacks at Wired magazine. EDAN may have been stillborn, but there is no shame in that. The question before us however, is this: ten years after The Digital Artisans Manifesto, what should one make of Imaginary Futures, Barbrook’s reflections on the history and prospects of the ‘information society’. Judged in the millennial light of another decade of globaloney; the NASDAQ implosion, the onslaught of military neoliberalism, and the rise of digital hives in Gurgaon and the neo-cities of the planet, whither the digital artisan?

The cover of Imaginary Futures shows the author as a seven-year old in front of the Unisphere, icon of the 1964 New York World’s Fair (and lately featured as backdrop for the climax of Men in Black.) The massive graticulated sphere, expressing the theme of ‘man’s achievement on a shrinking globe in an expanding universe’, was erected on an ancient tidal marsh destroyed by Robert Moses, New York’s modernising commissar, in preparation for the 1939 World’s Fair. His team of New Deal ‘creatives’ baptised the paved-over wetland, in a flight of Orwellian onomastics typical of (sub)urban development everywhere, Flushing Meadows.

Despite the attractions of the Christian Science and Vatican pavilions, the Johnson Wax theatre, and the world’s largest cheese (from Wisconsin), the 1964 Fair effectively went bankrupt by falling 20 million visitors short of projections, and had to be bailed out from the public purse.

The young Barbrook was quite unaware of the dodgy finances or the boondoggles behind international expositions as he gazed at the giant rockets in the Space Park, en route to Boston for a year during which he recited the loyalty oath to the US flag and watched a lot of American TV – ‘seminal events in my life’. Only later did he figure out why he was in the New World; his father, an English political scientist and Labour Party apparatchik, was on a CIA-sponsored Cold War exchange visit. God Save the Commonwealth is the title, not of a lost Alan Bennett play, but of Barbrook père’s electoral history of Massachusetts, based on research conducted during the year at MIT, doing his bit to cement the special relationship. Tony Blair’s recent appointment to the schools of management and divinity at Yale, to lecture on faith and globalisation, continues the tradition.

From Camelot to Canary Wharf

Barbrook frames Imaginary Futures – billed as the (oneiric) history of artificial intelligence, the information society, and their confluence in the Net – within his own personal trajectory, from Cold War America to post-Big Bang London. At the same time, he constructs it by means of an interesting visual conceit as a kind of return, thanks to the collage artistry of Alex Veness, whose ‘retro-fabulous’ illustrations interlard each chapter. That is to say, the last image in Imaginary Futures has Barbrook once again standing in front of the Unisphere. Not in holiday shorts and sandals this time, but, forty odd years on, in working denim (or is it serge?). The checkered shirt and proletarian cap seem intended to draw our attention away from his occupation as a lecturer in Hypermedia Studies and suggest a workerist identification with Europe’s traditional artisanate, albeit with arms folded in a gesture of repose or supervision.[2]

Imaginary Futures endorses the position taken in the 1997 manifesto by asserting that the internet, despite being implicated in the apparatus of geopolitical domination, is a liberatory medium. Therefore, the net is truly a revolutionary instrument of general emancipation, and should be reclaimed as such by the makers of history (‘digital artisans’) emerging from the networked workplace. The book elaborates upon a print-on-demand pamphlet entitled The Class of the New, published in 2006, and billed as a ‘Creative Workers in a World City’ project. Apparently intended as an intervention in the cultural politics of the administration of Ken Livingstone, London’s then new mayor, and his plans for a city congenial to the ‘creative industries’. The pamphlet traces what Barbrook describes as the ‘intermediate’ class of wage earners, those without capital but in possession of ‘other potent sources of economic power: educational qualifications and cultural knowledge’, in their various guises as ‘creatives’, ‘digerati’, ‘symbolic analysts’… all the way back to Hegel’s ‘civil servants’ and Saint-Simon’s ‘industrials’.

Image: Material Labour by Alex Veness. Richard Barbrook at Alex Veness' studio, England 2006 at the Unisphere

Barbrook describes his modus operandi as ‘data-mining’, and that sounds about right. The result indeed bears the marks of extractive industry, but it is hardly adequate as history. Arguing that like Walter Benjamin he ‘discovered that his collection of research notes was turning into a book in its own right’, Barbrook only embarrasses himself in claiming The Class of the New as a kind of Arcades Project for the digital epoch.

Nevertheless, the pile of quotations gathered by Barbrook about the historical ‘intermediate’ class does vividly reveal a sectoral continuity. To believe, however, that the current batch of ‘privileged creatives’ working in the re-purposed warehouses of neoliberalised cities is the bearer of a special historical destiny requires some imaginative overtime. When Barbrook declares, ‘Our utopias provide the direction for the path of human progress’, he could have been channelling the telegraphy-struck disciple of Saint Simon who in 1852 predicted an imminent utopia thanks to ‘a perfect network of electric filaments’. Communication as blessed community. In fact, far from suggesting that his network of digital artisans are the makers of universal history – the grave-diggers this time around – The Class of the New attests only to the recurrent sameness of modernity’s clerisy, and to the technical recomposition of labour under capitalism. Instead of retro-fabulous melodrama, Barbrook’s time would have been better employed doing some critical historical semantics on the abuse of terms such as ‘creative’ and ‘artisan’.

Barbrook is not unaware that the most spectacular objects on display at the 1964 World’s Fair – rockets, computers, atomic reactors – were primarily state-funded instruments of globalised warfare. However, he has no way to ask himself Turner’s generative question animated by events taking place, in the same year of 1964, not in Flushing Meadows, but on the Berkeley campus. Turner reproduces a quirky photograph of striking Free Speech activists wearing IBM computer cards around their necks as signs of protest. (There was, as it happens, another face to Flushing Meadows in 1964, quite invisible from Barbrook’s optic, namely, the motorised Critical Mass, or ‘stall-in’, blockading local roads at the opening of the World’s Fair, organised by black radicals from the Brooklyn branch of Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) protesting urban poverty and racism. Flyers urged New Yorkers to ‘drive awhile for freedom.’)

Image: Free Speech marchers at Berkeley wear computer cards as signs of protest, December 1964. Photograph by Helen Nestor. Used by permission of the photographer and courtesy of Helen Nestor Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Barbrook could not entertain Turner’s question because he is committed to the premise that post-war ‘imaginary futures’ present an essentially unchanging vision, or in the words of his opening chapter, ‘The Future Is What It Used To Be’. He attempts to buttress this assumption by a striking – and ahistorical – legerdemain, and by shifting our focus again to the Unisphere. Veness’s image of Barbrook in front of the unisphere posits the desired historical immutability – ‘[t]he frozen time of the 1960s past is almost indistinguishable from our imaginary futures in the 2000s.’

But, in reality, the semiotics of the Unisphere have changed radically since 1964. It had come to connote a world shrunk by fibre optics rather than ICBMs, the domain of Tim Berners-Lee rather than Werner von Braun. This is not to deny some enduring affinities, of the kind that Marshall McLuhan trades on for his ‘global village’ notion. The Unisphere and, one could say, globes in general appeal to universalists of various stripes – neo-Kantians, humanitarian liberals, expo bureaucrats, UN one-worlders, transnational corporations, Earth First!ers and, evidently, cyberhucksters. We are fortunate that in Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination the cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove has clarified the attraction of images of the planet which show no borders. Globes were from the beginning ‘emblems of sovereignty’ (it comes into the language in this sense in 1614). They became the playthings of monarchs and navigators, familiar as props in Renaissance portraiture.

Given the centrality of the globe to Barbrook’s project, it would have served his purpose to explore globalism as a set of material practices and representations, as well as conceptual and 3D models. Cosgrove further reveals how globalism’s force, with roots deep in Western imperial history,

derives from the arresting concept of the earth as a single space made up of interconnected life systems and a surface over which modern technological, communications, and financial systems increasingly overcome the frictions of distance and time to achieve coordinated simultaneity.

Cosgrove concludes his study with a meditation on cultural appropriations of the famous NASA photograph AS17–148-22727, taken during the final Apollo mission in 1972. The NASA earthscape as image and icon was quickly staked out by both environmentalists (to promote Earth Day) and by capital – for example, Mobil’s advertising campaign showing a miniature and vulnerable globe resting in the open hand of a white-coated scientist.

Weary Giants of Flesh and Steel

Among the first to exploit this representation of globalism was an environmentalist and a capitalist, both. Stewart Brand used the NASA photograph as logo for the Whole Earth Catalog, which became the bible of rusticating hippies and back-to-the-landers, who imagined an alternative green world powered by appropriate technics, available for purchase by mail order. The miniaturised computer – Mac, not HAL – lay some distance ahead. Turner tells the fascinating story of the transition from counter- to cyber-culture by focusing on the life, a fully contextualised biography, of Steward Brand – infantryman, photographer, student of Buckminster Fuller, cybernetician, romancer of the Red Man, new communalist, networker extraordinaire, and, from the get-go, entrepreneur. He didn’t call it a ‘catalog’ for nothing!

For a brief moment, in the doldrums following the demise of his Whole Earth Catalog, the man who had once announced ‘We are as gods and we might as well get good at it’, managed a certain perspective on his situation: ‘I’m a small business man’, said Stewart Brand. Later, in the mid-1970s, he became enthused by plans for terraforming and the construction of massive colonies in space; Turner insightfully suggests that

these dreams would reappear in the rhetoric of cyberspace and the electronic frontier. Unlike cosmonauts, these are phantasms that never have to touch the earth. More recently, however, in keeping with his digital hucksterism and circumglobal summitry, his focus has once again expanded – he aims to build a perfectly accurate ten thousand year clock.

Using primary source material and extensive oral histories, Turner brilliantly excavates the strange contradictory career of key computational and cybernetic metaphors and their material conditions of possibility. Turner tracks the trickle-down of Operational Research and small group work pioneered by Kurt Lewin during World War II, as well as the popularisation of cybernetics by Norbert Wiener, who also looms large in Barbrook’s account. On this topic I would suggest going directly to the pioneering studies, Norbert Wiener and John von Neumann: From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death and The Cybernetics Group, by Steve Heims, to whom both authors are indebted. The informal collaborative counter-cultural style that, as Turner shows, was paradoxically spawned within the military-industrial-academic complex finds its echo eventually in the Friday dress code of corporations everywhere. Cold War executives whose ‘hands ached from years on the corporate ladder, and [whose] souls had begun to wither beneath their suits’, traded worsted for denim. Turner describes how, by the end of the 20th century,

bureaucratic organizations had begun to lose their shape … hierarchies have been replaced by flattened structures, long-term employment by short-term, project-based contracting, and professional positions by complex, networked forms of sociability.

The current state of the art can be found at Google headquarters.

From quite different perspectives, the liberal Turner and the Marxist-McLuhanist Barbrook misconstrue the Californian counter-culture, both of them blind to significant anti-authoritarian and radical strands in the ’60s milieu. Barbrook makes a much more comprehensive mess of it, by viewing post-war America through the pinhole of a Trotskyist camera obscura. Accordingly, the landscape is upside down, and bizarre to say the least: the central figures of what Barbrook calls ‘the Cold War Left’ turn out to be … Daniel Bell and Walt Rostow. Perhaps the radical apotheosis of a Harvard sociologist and an MIT technocrat is part of an attempt to recuperate Barbrook’s father, the CIA-funded Cold Warrior.

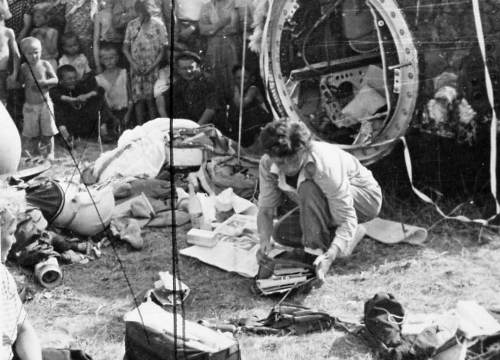

Image: Cosmonaut Valentia Tereshkova, first woman in space, beside Vostok 6, Russia/Kazakhstan border, June 19, 1963. Photograph Courtesy of Lina Kohonen, Russian State Archive (RGANTD), Moscow

Apart from the historiography and its framing, there are some important epistemological stakes in the matter of digital utopianism that neither Barbrook nor Turner come close to grappling with, since they tacitly agree, in the manner of Marxists and liberals, about the neutrality of technics. Neutrality in the sense that technologies are presumed to have good or bad uses, correct or incorrect ‘interpretations’, free or fettered ownership – in other words, a functionalist metaphysics. But artefacts and technical systems, without being self-determining, do have a value-slope; they conduce to certain forms of life and consciousness, and against others. On the other hand, the value-slope of a technology is far from easy to estimate, and in any case there is never closure with respect to consequences or reception. This is not to say that Armand Mattelard, the historian of semaphore and electric telegraphy, was wrong to assert: ‘Communication serves first of all to make war.’[3] Or, analogously, that Barbrook is beside the point in claiming that the internet was an integral legacy of the Cold War fostered by the CIA in response to the perceived threat of Soviet scientists and engineers’ invention of horizontal networks. Nevertheless it should be salutary for prophets of the net to recall that Adorno and Benjamin could so fundamentally disagree about the popular revolutionary potential of cinema as a medium. What then of the internet as an instrument of general emancipation, if, as it now seems, the technics of the virtual conduce to the production of monstrous subjects who are incomplete, lacking, overwhelmed inside. The corollary is a politics of resentment, and a paranoia that flourishes on the cusp of a plenitude always under threat of social death and incorporation into the machine.

The contrasting codas to these two books reflect quite different epistemic stances, not so much toward the potential of the internet as a medium, but to the past and to the future. Turner deploys the methods and tools – evidential and archival – of the historian, and closes From Counterculture to Cyberculture on a modest and conditionally prognostic note:

we remain confronted by the need to build egalitarian, ecologically sound communities. Only by helping us meet that fundamentallypolitical challenge can information technology fulfil its counter-cultural promise

Barbrook, by contrast, data-mines the past – mostly secondary literature – in pursuit of his own imaginary future, which he pulls out of the hat on the last page. A strange hybrid from the political bestiary, called ‘libertarian social democracy’.

Image: Fall 1969 cover, Whole Earth Catalog. Reproduced under the GNU Free Documentation License

This fabulous creature aside, it is significant that in both Barbrook’s and Turner’s accounts of digital utopianism lurks the threat of catastrophe. Barbrook registers the fact that beneath the PR surrounding the rockets and computers at the World’s Fair lay technologies ‘invented for a diabolic purpose: murdering millions of people.’ Turner similarly notes that ‘Brand suffered from a deep fear of technological Armageddon,’ and that as a child he had nightmares because

somebody compiled a list of prime targets for Soviet nuclear attack and we [Rockford, Illinois] were [number] 7, because of the machine tools.

Digital utopianism, then, could be said to have two aspects: pragmatically, in the circuits of capital, it constitutes a discourse directed at investors, but turned inwards it represents a kind of redemptive sublimation in the face of fresh apocalyptic forebodings. Not Carl Sagan’s nuclear winter this time around, but a sense of global, ecological doom.

For the doom merchants and the utopians I have a couple of forecasts of my own. I predict that the new clerisy – call them ‘creatives’ or whatever you like – will continue to do the bidding of those who own the world. The intermediates and their masters will all be dressed in denim. The men in black will mainly be pallbearers at the 21st century’s entirely predictable varieties of apocalypse. For a start, the billion victims of the cigarette, that miniature hi-tech killing machine, Big Tobacco’s digital utopia.

Footnotes

[1] Richard Barbrook and Pit Schultz, The Digital Artisans Manifesto, http://www.b2u2.net/manifesto.html

[2] Artisanate – ‘This was a class in possession of its own means of production – tools and skills; which enjoyed high levels of literacy; was typically located close to the centre of capital cities; and, last but not least, was geographically mobile – a mobility symbolized by the famous tours of young apprentices within or beyond their own countries.’ Perry Anderson, ‘Internationalism: A Breviary’ New Left Review, 14, March-April 2002.

[3] Armand Mattelard, Mapping World Communication: War, Progress, Culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. p.xi.

Info

Richard Barbrook, Imaginary Futures: From Thinking Machines to the Global Village, London: Pluto Press. 2007.

Richard Barbrook, The Class of the New, London: Openmute. 2006.

Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, University of Chicago Press. 2006.

Iain A. Boal <boal AT sonic.net> is a social historian of science and technics, associated with Retort, collective authors of Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War, London:Verso, 2006

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com