Duck! You Regeneration Sucker

David Panos & Anja Kirschner's film, Trail of the Spider, allegorises the public-private land-grab known as ‘urban regeneration' using the form of the Spaghetti Western. This is no shallow postmodern genre surfing, writes Neil Gray, but a passionate re-engagement with history for the sake of the present

Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

- Walter Benjamin

Watch them now. All bold, like they discovered the place [...] maybe we can't stop them, but we can't give them an easy ride. Let them feel some loss!

- Doctor Dynamite, Trail of the Spider

Stepping confidently out of the specialised ghetto of ‘artists cinema', Anja Kirschner and David Panos' most recent film, Trail of the Spider (2008), dramatically explores the material and psychological conditions brought on by gentrification through the refractory prism of Hollywood and Spaghetti Western genres. The film, a self-described ‘Western made in London and Essex', deploys the vanishing frontier motif and subversive Western genre tropes in complex yet unambiguous terms to examine contemporary ‘regeneration' strategies in East London. By doing so, it skilfully mobilises multiple historical narratives into a fraught but productive relationship with the present. The universal theme of gentrification (now writ large as a central productive pillar of global economic strategy) re-imagined through the tropes of the Western, conjures a rich inter-textual feast for all those interested in the burdened intersection between cinema and politics.

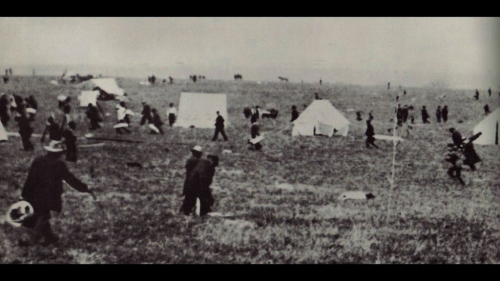

All images: stills from David Panos & Anja Kirschner's Trail of the Spider

The plot is replete with all the key motifs of the Spaghetti Western genre: an existential anti-hero; ‘the Man with No Name'; a wronged woman; the inexorable forces of modernity in the form of surveyors, land barons, and the steam train; and pusillanimous townsmen, lawmen, and small businessmen seeking personal profit over collective gain. The Man with No Name wanders this unruly ‘genre setting', seeking only rest and solace, while surveyors haunt the frontier lands, mapping and carving the land into new enclosures of time and space.i Frontier and genre conventions are deployed here not as retro gestures, or as deconstructive discourses on signifying practices. Rather, they are marshalled as part of a layered discourse dealing critically with a range of historical experiences and registers. Much of the viewing pleasure in Trail of the Spider is derived from this engaged re-working of historical and aesthetic references: an implicit challenge to an art world culture of repetitive reference and citation that almost uniformly fails to re-deploy and transform culture for radical social ends.

Stewart Home, after Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman, has argued that the difference between detournementii and appropriation is precisely the difference between a transformational praxis and a slavish citation which refuses to theorise, never mind renovate, its historical moorings.iii The currents which inform Trail of the Spider, by contrast, are rooted in the objective conditions of postwar Europe and filtered through the lens of historically situated subjectivity. The idea for the film, according to Panos, was derived in part from Munich-born Kirschner's ‘very German interest in cowboys'. The devastation of Germany's production and distribution facilities during WWII granted the US film industry an industrial stranglehold on West German cinema, rendering Germany prone to a ‘re-education' programme in the form of re-released US films - a vast new market for the products of American culture. The cowboy - bolstered by the Hollywood studio system - was then the archetypal American hero; in his celluloid form, devoid of competition, he was ready to conquer German cinema. The terms of this occupation were disinterred by a character in Wim Wenders' Kings of the Road (1976) who ruefully observed, ‘The Yanks have colonised our unconscious.'

The cowboy narrative, however, developed along divergent lines in the GDR, where production facilities were rebuilt relatively soon after the Nazi era. The film industry quickly developed its own ideological contours under Communist rule. Relative autonomy from US influence spawned, by the 1960s, the bastard Indianer Filme: an estranged, inverted breed of Western where cowboys were capitalists and Indians were proto-communists challenging North American capitalism. It is this non-compliant appropriation of the Western, shorn of regressive Stalinist ideology, that irradiates the narrative and provides a rebellious genre background for Trail of the Spider. The Man with No Name character (immaculately played by Hackney activist Floyd) finds echoes in the subversion of racial ideology in R.W. Fassbinder's Whity (1970), the heroic ‘half-breed' avengers of Sergio Corbucci's Navajo Joe (1966), and Enzo G. Castellari's Keoma (1976). ‘Marnie's place' (the tavern in Turnwood) deliberately evokes Joan Crawford's gender-busting saloon in Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954), and Marlene Dietrich's ‘Chuck-a-Luck' rebel hideaway in Fritz Lang's ‘feminist' Rancho Notorious (1952). Meanwhile, references to Django (1966) and The Great Silence (1968) impregnate the film with Corbucci's ‘communist' take on the Spaghetti Western genre more com- monly associated with cruel, existential pathos.iv These references (and many others) work to inscribe dissenting discourses into the prosaic conventions of genre narrative, and more importantly, into the discursive terrain of contemporary land-grab scenarios. Yet the process by which Kirschner and Panos redeploy history and genre myth recalls most forcefully the philosophical method by which Walter Benjamin set out to rescue history from ‘historicism's bordello'. Benjamin's conception of montage (‘the ability to capture the infinite, sudden or subterranean connections of dissimilars as the major constitutive principle of the artistic imagination') fought a constant battle on behalf of history's victims, in order to detonate the slumbering time of the present with the fractious constellations of the past.v Interviewed about one of her previous films, Polly II: Plan for a Revolution in Docklands (2006), Kirschner said:

To some extent the plot of Polly II was based on actual events from the 18th century [...] But I'm not depicting or referencing these moments so they can be measured against so many subsequent defeats or presented as easily digestible celebrations of ‘heritage' or downright nostalgia [...]. Rather, I use them because they penetrate the present like so many callings and loopholes whose explosive potential still speaks to us.vi

These ‘callings and loopholes' are dramatically precipitated when the Man with No Name observes Surveyor's masked henchmen lynching a local man (the masks cite the hooded Klan gunmen in Django). A close-up of a wound in the Man with No Name's stomach dissolves into a rapidly edited montage that violently implodes a dense personal and collective history of repression and injustice (signified here by a lurid red filter). Later, when the Man with No Name is beaten to near unconsciousness by Turnwood for his bounty, the red filter is re deployed as a deep signifier of emotional as well as physical turmoil.vii This defeat is given historical and cinematic resonance by the incessant, rhythmic pounding of a steam train - that potent harbinger of 19th century change - and the beating of fists, on a soundtrack pulsing with the pressure of brutal and seemingly irresistible forces.

Kirschner and Panos understand, just as Benjamin did, the need to fight and re-fight the battles of the past. The film re-enacts and reorders the repressed racial history of the West through scenes and inter-titles that reference a frontier history more commonly epitomised by erasure and disavowal (up to one in three cowhands were African American). The moribund landscapes of contemporary East London - through which the Man with No Name restlessly wanders - are given a mythic register and re-animated to mirror ‘The Unassigned Lands' where the US government of the 1860's forced Indian tribes to ‘cede back' inalienable territory so that settlers could pursue a ferocious land-grab. ‘The Trail of Tears', through which the Man with No Name makes his sorrowful way to his old flame Marnie, condenses his journey with the forcible displacement and relocation of Indian tribes from the American South to Arkansas and Oklahoma after the passage of the Indian removal Act in 1830. ‘The Great Dismal Swamp' (evoked in the film through judicious close-ups of snakes, lizards and spiders!) is both the location for ‘Turnwood Town' and a reference to an actual location in North Carolina where runaway settlements (‘maroons') of African and Native Americans escaped from slaveholders to form their own agricultural and trading communities - rebel communities which ‘served as beacons to discontented plantation slaves and drove slaveholders to fuming anger.'viii

The interaction of these mythic landscapes with present tense actuality ‘brushes history against the grain', placing elements of past and present into new dialectical images that attempt to address a critical understanding of history.ix Patterns of montage within and between images allow the landscape to be read as a palimpsest, containing multiple discursive layers. The epic Western landscape, for instance, is imaginatively conjured from landfills, ‘wastelands' and gravel pits with direct links to the construction of the 2012 Olympic Park, conflating both historical and contemporary land-grabs. Meanwhile, regular insertions of 19th century paintings of the West reinforce the genre setting, and at the same time illustrate and comment on the constructed manner in which the West has always been, and continues to be, represented.

Pioneers and Piriahs - The New Urban Frontiers

If Hollywood wanted to capture the emotional center of western history, its movies would be about real estate. John Wayne would have been neither a gunfighter nor a sheriff, but a surveyor, speculator, or claims lawyer. The showdowns would appear in the land office or the courtroom: weapons would be deeds and lawsuits, not six guns.

- Patricia Limerick Nelsonx

The positivist idea of the frontier and its inverse relation to wilderness and ‘the other' are particularly pertinent here.xi Neil Smith charted this territory when he established the ongoing currency of Frederick Jackson Turner's prototypical 1893 essay, ‘The Significance of the Frontier in American History'.xii Turner envisioned the expansion of the Western frontier as:

the outer edge of the wave [...] the meeting point between savagery and civilization [...] interpenetrated by lines of civilization growing ever more numerous.xiii

In this interpretation, the frontier is represented as an evocative combination of economic, geographical and historical advances by robust pioneers. Yet Turner's frontier line was extended less by individual pioneers and rugged homesteaders and more by ‘banks, railways, the state, and other collective sources of capital.'xiv In the present era, the mythology of individualism persists through the ideology of neoliberal capitalism. By the mid-to-late 20th century, the potent imagery of wilderness and frontier was being re-applied to inner city areas in major cities back East. Inner city slums were increasingly demarcated as ‘urban wilderness' or worse ‘urban jungles' in a ‘discourse of decline' that came to dominate representations of the inner city.xv By the 1970s and '80s, market-led discourses of urban renaissance retooled frontier imagery (with the African American as its stigmatised ‘other') to legitimise ‘a political geographical strategy of economic reconquest'.xvi The property market unleashed a wave of ‘urban scouts', ‘urban pioneers' and ‘urban homesteaders' on the margins of the inner city. And just as the original ‘pioneers' reductively envisioned native Indian populations as no more than a constituent part of the wilderness, so the ‘new folk heroes of the urban frontier' saw the residents of the contemporary frontier as ‘not yet socially inhabited' or ‘less than social'.

Trail of the Spider exhumes this discursive current of conquest and legitimation from the opening scene. In a terrific panning shot across a massive, moribund East London landfill site, a voiceover, culled from one of the Communist Indianer Filme, works with and against the image to stridently conflate the ideas of frontier conquest, American capitalism and ruthless displacement with current speculative land-grabs in the East End of London. The mythologised tracts of contemporary London stand in for the historic Unassigned Lands (crackling with effect-laden lightning) where the remnants of a splintered resistance eke out a hounded existence in a rapidly diminishing social space; a space where surveyors, surrounded by ‘security', chart ‘the hitherto unmapped territory' of potential capital investment. Gazing out over the land for investment opportunities, the Chief Surveyor (in an assuredly pompous performance by Robin Laine), propounds the real meaning behind the reductive ‘civilization/wilderness' binary:

Look at the lay of this great land. Who would have thought that one day we would attach value to this wilderness?

The film-makers have stated that the main concern of Trail of the Spider was to allegorise and question the ‘the shifting and shrinking space for collective social and political agency, self-determination and dissent' in an urban reality increasingly dominated by large-scale urban gentrification - what Neil Smith has ominously, if somewhat a-historically, described as an ‘unassailable capital accumulation strategy for competing urban economies'.xvii Like Benjamin and his close friend Bertolt Brecht, these concerns are expressed with an understandable degree of historical pessimism (Benjamin and Brecht's thought in the '30s, after all, was shaped by the degeneration of the USSR and the seemingly inexorable victories of fascism). Yet those unpropitious times also grounded an immanent, dialectical view of history, divested, for the most part, of ideological myopia. As Brecht once recommended: ‘Don't start from the good old days, but the bad new ones.'xviii

In these bad new days, the relevance of Trail of the Spider should be readily apparent. ‘Sugar-coated' promises of community ‘regeneration', can't hide the fact that what's really occurring is gentrification on an unprecedented scale (with all it's ugly connotations of class displacement). The prosaic reality of rampant property speculation is dramatised near the conclusion of the film, when a contemporary, fictionalised ‘land race' on an open tract of land in London's East End is compared (through the insertion of archival photographs) with the Oklahoma land race of 1889. The event saw Indian squatters forcibly removed from land that had been promised to them so that white settlers could ‘compete' for plots of land. The conflation of these narratives of speculation and enclosure, with all the legalistic and judicial apparatus that profits from them, nakedly reveals the consistent current of brutal, competitive self-interest that lies behind capitalist accumulation strategies. Displacement, advanced marginality, and the ruthless disposal of public assets are the necessary contingencies of this totality.xix

Hardt and Negri usefully theorise representative democracy as a ‘disjunctive synthesis' that simultaneously ‘connects and separates' citizens from the social body.xx In this context resistance is typically either forced to the margins or defused through legalistic, reformist channels. In both Polly II and Trail of the Spider, Kirschner and Panos acknowledge and question the problem of recuperation and mediation. But rather than merely contemplating their own alienation, their creative practice emerges from praxis in everyday struggles against gentrification in East London. Most of the people in the film are friends or people they've met through activist campaigns in Hackney - including the Broadway Market occupation.xxi During the occupation, they met Floyd (The Man with No Name), and a prior friendship was cemented with John Barker (‘Doctor Dynamite'), whose experience with the Angry Brigade in the early '70s adds a critical, self-reflexive dimension to an intimately staged campfire scene (the dialogue concerns the potential of sabotage in the face of repression and retreat).xxii Meanwhile, Marnie's impassioned speech (singer/performer Claudette Bonney in a great performance) is partly based on Spirit, a local Jamaican shopkeeper and neighbourhood friend facing eviction orders in a rapidly gentrifying Hackney. This social dimension of Trail of the Spider concurs with Brecht and Benjamin who saw friendliness as a ‘minimum programme of humanity'.xxiii At the same time, it locates their film practice alongside Peter Watkins, one of Britain's most marginalised and vilified film-makers. Watkins work with non-professional actors has consistently attempted to break down the petrified, alienating separation of artist and audience by encouraging the public to directly participate in representations of history - ‘past, present and future'.xxiv

David Panos described a recent packed-out screening of Trail of the Spider in Hackney which ‘somehow recreated the reception to the Spaghetti Westerns in Jamaica and other post colonial countries'. Such a reaction echoes the scene in Perry Henzell's The Harder They Come (1972), where the fugitive anti-hero ( Jimmy Cliff ) watches Corbucci's anti-hero Django (a major influence on Trail of the Spider) annihilate a gang of racist henchmen with an enormous sub-machine gun. The wild amusement of the crowd is undoubtedly borne from the Jamaican audiences recalcitrant experience of independence struggles against British colonialism. Trail of the Spider seeks a similar kind of resonance with its audience. In an aesthetic register that confronts the ossified conservatism of high modernism, and the mindless quotation of postmodernism, the film also brushes popular genre conventions against the grain in an attempt to engage and re-arrange the audience's experience and knowledge of history. This way of working with history isn't mere source material for a reified and institutionalised art practice; instead historical forces are represented in such a way that they provide a genuine motivational connection to the possibilities of social change. As Nietzsche said in The Use and Abuse of History, ‘We need history, but not the way a spoiled loafer in the garden of knowledge needs it.'xxv If Nietzsche's sentiment is true for history, it is also true for a contemporary urban reality in desperate need of radical transformation.

Neil Gray <neilgray00 AT hotmail.com> is a writer and film-maker based in Glasgow

Info

Trailer for Trail of the Spider (2008): http://www.anjakirschner.com/trailtrailer.html

Trailer for POLLY II - Plan for a Revolution in Docklands (2006): http://www.difficultfun.org/items/pollytrailer.html

Footnotes

i The phrase belongs to Paul Willemens. Paul Willemens, ‘An Avant-Garde for the ‘90s' in Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory, British Film Institute, Indiana University Press, 1994, p.157.

ii Defined as ‘The reuse of preexisting elements in a new ensemble' in ‘Detournement as Negation and Prelude', p.55, Ken Knabb ed., Situationist International Anthology, the Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981.

iii Stewart Home, Bubonic Plagiarism: Stewart Home on Art, Politics & Appropriation, Sabotage Editions, p.10.

iv Akira Kurosowa's denuded Marxism led him to the pessimism of Yojimba (1961), the chief inspiration for Sergio Leone and the Spaghetti Western genre. No wonder that Kurosowa's exotic ‘depth', shorn of his earlier politics, appealed so much to Hollywood luminaries George Lucas and Steve Spielberg.

v From Stanley Mitchell's penetrating introduction to Walter Benjamin: Understanding Brecht, Verso, 1998, p.xiii.

vi http://www.anjakirschner.com/polly2/reviews.htm

vii A device that vividly evokes the cinema of Michael Powell and Emeric B. Pressburger, for instance, Black Narcissus (1947) and Peeping Tom (1960), and their interest in the irrational frictions lurking beneath the carapace of the rational mind.

viii http://www.anjakirschner.com/trailofthespider/trailpamphlet.pdf

ix Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, Pimlico, p.248.

x Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West, New York: Norton, 1987, p.55.

xi For an analysis of how frontier imagery is mobilised as a neoliberal alibi for creative destruction of inner city areas: in this example, the East End of Glasgow. See Neil Gray, ‘The Clyde Gateway: A New Urban Frontier', Variant, Issue 33, Winter 2008, (forthcoming online).

xii Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City, Routledge, 1996.

xiii Ibid, p.xiii.

xiv Ibid, p.xvi.

xv The phrase is borrowed from Robert Beauregard, Voices of Decline: The Postwar Fate of US Cities, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1993.

xvi Neil Smith, op. cit., p.xvii.

xvii Neil Smith, ‘New Globalism, New Urbanism' in Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe, Blackwell Publishing, 2002, p.96.

xviii Walter Benjamin paraphrasing Brecht's critique of Lukács on realism. ‘Conversations with Brecht' in Walter Benjamin: Understanding Brecht, Verso, 1998, p.121.

xix Advance marginality is described, somewhat long- windedly by Loic Wacquant, the originator of the term, as: ‘the novel regime of sociospatial relegation and exclusionary closure [...] that has crystallised in the post-Fordist city as result of the uneven development of the capitalist economies and the recoiling of welfare states [...]'. Loic Wacquant, Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality, Polity Press, 2008, p.2.

xx Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude, Penguin Books, p.231-247.

xxi For background see, http://www.metamute.org/en/The-Re-Occupation

xxii For a highly readable account of this period see Stuart Christie, Granny Made Me an Anarchist: General Franco, The Angry Brigade and Me, Scribner, 2004, p.318-411. See also John Barker, Transgressions: A Journal of Urban Exploration, Issue 4, Spring 1998, Salamander Press, p.101-107, for Barker's own take on the legacy of the Angry Brigade's actions (online: http://www.geocities.com/pract_history/barker.html ).

xxiii Walter Benjamin on Brecht's poem, ‘Legend of the Origin of the Book Tao Te Ching on Lao Tzu's Way into Exile' in Walter Benjamin:Understanding Brecht, Verso, 1998, p.74.

xxiv See, http://www.mnsi.net/~pwatkins/part2_home.htm for more on Watkins method and filmography.

xxv Quoted in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, Pimlico, p.251.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com