The Dark Arts

Gregory Sholette’s book, Dark Matter, provides a useful collectivising term for those artists who produce the art world from below. But, wonders Stefan Szczelkun, how can we talk about cultural exclusion without thinking seriously about class?

When the excluded are made visible, when they demand visibility, it is always ultimately a matter of politics and a rethinking of history. This is often the case with artists collectives.

– Gregory Sholette

The ‘dark matter’ in the title of Gregory Sholette’s book refers to all the human creativity that is excluded from the mainstream art world. The book is a dense interweaving of political contexts, theory, accounts of radical art activity and considerations of the archive, mainly in a US context. The structure of the book is loosely related to Sholette’s involvement in a series of political manoeuvres – the first of which is the Political Art Documentation/Distribution group that was set up after a call from Lucy R. Lippard in 1980. The PAD/D collection was donated to New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) archive in 1989. For its author, the subversive implications of this donation provides a recurrent fascination throughout the book.

Following his account of this earlier history is a chapter based on Sholette’s involvement in a group called REPOhistory in New York. Initiated with a series of triangles put up in public in 1994 to mark the death of Marsha P. Johnson, a leading LGBT activist, it subsequently led to the erection of a series of nine similar triangles under the project Queer Spaces.

Sholette then discusses the over-abundance of signs, creativity and collections heightened by our present level of commodity accumulation. Two artists’ groups that worked critically in this area were Public Collectors and Temporary Services. Public Collectors recognise and bring attention to:

The inventiveness of the everyday, the commonplace, and the nondescript multitude. In the age of deregulated aesthetic practice such dark matter inevitably intervenes within the valorisation process of official artistic production.1

Temporary Services ‘seeks to generate a non-market, non-accumulative economy of generosity.’2 The account of their Chicago based project of 2000, Free for All, reminds me of the Free Stuff Parties organised by UK artist Mark Pawson at around the same time. This section ends with a discussion of the more confrontational actions of Etcetera in Argentina in 2002: the anti-BP actions of Liberate Tate in London in 2010 and Yomango’s surrealist theft actions from 2003 in Barcelona, Spain, which seem especially relevant now in the light of the recent rioting in Britain. The collective gesture of Yomango, which means simply ‘I steal’ in Spanish, clarifies the symbolic dimension of looting.

Sholette goes on to examine Critical Art Ensemble as one of the leading ‘tactical media’ groups of the last decade. Sholette himself was involved in supporting the defence of CAE member, Steve Kurtz, who was charged with biochemical terrorism following 9/11. Kurtz was finally acquitted in 2008 after a long, hard court battle, but Sholette does not discuss his own support role here. He claims that CAE’s artwork, Molecular Food Invasion, used the art gallery as a platform for public discussion.

Finally a chapter entitled ‘Mockstitutions’ on organisational forms and mock institutions focuses on The Yes Men and other artists’ groups. This includes some original survey research into 67 of these groups, which I’ll come back to.

A recurrent theme in Dark Matter is that of subverting dominant cultural values from within the archives. What do the mainstream museum archives like MoMA’s gain from taking records of artists’ dissent into their care? Sholette’s idea is that these stored materials are ‘a mark or bruise within the body of high art. The system must wear this mark of difference in order to legitimate its very dominance. Absolute exclusion is out of the question.’ Sholette suggests that these ingested materials will undermine the system and what starts with a ‘bruise’ can lead to an ‘infection’ of the whole body:

The perforation of a once suppressed archive exposes the wounds of political exclusions, redundancies, and other repeated acts of blockage that wholly or partially shape this emerging sphere of dark-matter social production.3

London’s Tate Gallery archive has a mission that is informed by the scale of its immense funding base and position as the national flagship museum of contemporary art. It assumes that it is best placed to interpret radical art history. Who else could take proper care of the archived originals? Who else could attract such esteemed and learned writers to interpret this material and produce a reliably normative view of the past? What they ‘forget’ is that, as an organ of the State, Tate is of necessity embedded in its ideological apparatuses, self-serving rituals and practices. At the end of the day, it is fundamentally unable to critique its paymaster – the system – except by way of mild chastisement or warning, so that the Leviathan can adapt, modernise and survive. Not only that but the difficulties of access that result from professional archive practices mean that the radical cognoscenti themselves find it hard to get their filthy hands on the material. Once ensconced in such a vault, radical material is unlikely to be activated in the revolutionary, or at least, playful and irreverent way that was often intended by the original sources. Sholette, however, takes a more optimistic viewpoint and states that:

These bits and pieces of generalised dissent resist easy visualisation, forming instead a murky submarine world of affects, ideas, histories, and technologies that shift in and out of visibility like a half submerged reef.4

In my experience, art world institutions will tend to intuitively reject anything which could undermine their wellbeing, or only accept an inoculating dose of such material.5 But Sholette allows the ‘dark matter’ that has sneaked through these portals much more power:

The archive is consuming its host, brandishing all the malicious resentment of the profaned, the philistine, the exile.

A materialising dark matter now confronts this so-called future as a grinning archive and antagonistic corpse.

[dark matter] directs our attention towards an ellipsis within the historical record where none is supposed to exist.

The archive has split open.6

Image: Liberate Tate's action marking the first anniversary of the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico at Tate Britain, 21 April 2011.

Dangerous Material

Is PAD/D dangerous material? Or is it enclosed, de-activated, isolated and neutralised material? Is not the stuff donated to these vaults only given for lack of any other more open activist-run alternative? What we need is more in-depth and independent studies of initiatives that put their material firmly and independently into the public domain. At the same time we need to demand better access to, and digital publication of, collections that the State would probably rather keep buried. This means a lot more clamour needs to be made about the importance of initiatives such as artists’ collectives.

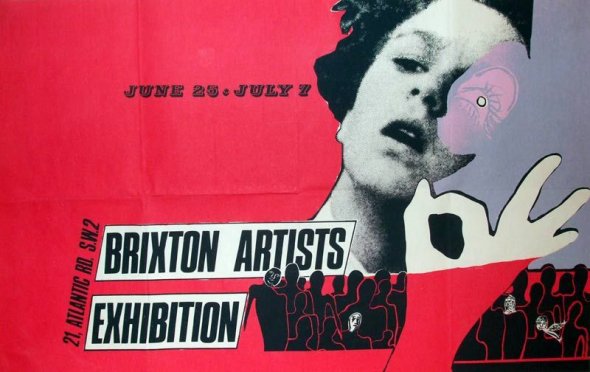

I should now admit that I have long pursued an engagement with dark matter, mostly of different genres to those considered in this book – mostly relating to larger collectives. In the last 15 years I have even tried to drag these things into the light of formal knowledges: from my 2002 doctoral study of Exploding Cinema at the Royal College of Art to my current active archiving, with many others, of the Brixton Artists Collective, 1983-86, as Brixton Calling!7 The material traces of which are, in spite of my reservations, heading to the Tate archive.8

Whilst doing the Exploding Cinema research, I became aware that the British Film Institute’s (BFI) London collection was thin with regard to amateur home movies on standard and Super 8, the technology that took filming to the masses from the ’60s onwards. When I approached them about housing archive material from Exploding Cinema, I was told that they did not take VHS tapes as they weren’t of professional quality. Of the 1,000 or more film-makers that had shown films in Exploding Cinema in the pre-digital period of my study, many left copies of their works with collective members on VHS cassettes. So, inflexible adherence to that rule meant that the films shown at Exploding Cinema are by and large not archived and likely to be lost to posterity. Whilst such rules are ostensibly about objective professional standards and so on, in fact they act as a filter on dark matter – in this case the zero budget self-made films of the 1990s. My study of the collective and its material traces and events are now archived but the actual works shown, the heart of what Exploding Cinema was about, are not included in the national archive of the moving image. My overall experience is that very little material from radical artists’ collectives is in public archives and what is there is hidden by unfriendly index terminology or other means.

Class and Exclusion

Sholette sees the new explosion of dark matter’s visibility via the internet as characterised by:

a lack of interest in abstraction coupled with a fondness for everything that was once considered inferior, low and discardable. Qualities that were anathema to modernist notions of serious art.9

He thinks that digital technologies have put much informal social production into the public sphere. Frustratingly, he does not theorise the relation of ‘low’ material and ‘informal’ production to class and in fact, at one point seems explicitly to reject a class analysis.

Tactical Media is [...] a rejection of most nineteenth and early twentieth-century leftist movements and of the idea that the working class is a unique and ontologically privileged force of social and historical transformation.10

On the other hand, he thinks that tactical media groups have emerged from a situation of ‘surplus talent’ and a what he calls, ‘prickly, working-class imagination’. He doesn’t go on to detail what he means by this prickly quality of imagination; instead, he goes back to a roll call of ’60s counter-cultural influences and somewhat loses his way in the process of considering ‘right wing’ dark matter.

Prickly Filters

In another prematurely aborted theoretical analysis, Sholette discusses the concept of the public sphere through Grant Kester’s dialogical aesthetics.11 He refers to Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge’s concept of a ‘counter-public sphere’ suggesting that a discourse on dark matter would mean, ‘constructing filters contrary to those of the market.’12 A good point, and it’s a pity there is no further discussion of what such ‘prickly’ friendly filters might look like.

One of the most interesting ideas the book puts forward is that dark matter, although deprecated, is essential to high culture. He claims that it plays ‘an essential role in the symbolic economy of art.’13 This is a claim that reappears through the book:

What is not recognised, what cannot be admitted by the maintenance crews of the high culture industry, is the degree to which not only the art world’s imaginary but also its economy is stabilised by the invisible labour of this far larger shadow economy. The material and symbolic sides of these economies endlessly amplify each other.14

He makes the point that all our informal conversations about figurehead art institutions help to maintain and reinforce their credibility and power. I feel this dependence of the art world on dark matter is true, in the same way that the owning class has a dependence on labour (which is magically reversed in their ideology). However, I don’t find Sholette provides the evidence to take this argument forward to the point that it could be used convincingly to argue for a radical redistribution of resources within culture.15

Art Glut

A set of unobtrusive art world institutions and practices by art critics, historians, collectors, dealers and administrators have ‘inscribed’ the antagonism shown by early modern artists and are themselves increasingly programmed, as if on rails, with little critical self-awareness. This results in an art world that is ‘afraid to admit that it is comatose’.

The book considers the mystery of the ‘glut’ of artists; ‘the normal condition of the art market’, as Carol Duncan pointed out in 1983.16 Sholette provides some useful information on this overproduction. For example, in the USA between 1970 and 1990 the number of artists doubled. In the EU, the numbers of artists is the same as the working populations of Eire and Greece. In London, the number of self-described artists comes second only to the number of people employed in the city’s business sector.17

Drawing on these insights, Sholette poses the following evergreen questions:

1. If this glut is commonplace and enduring, then what ‘material benefit’ does the art world get from this ‘redundant workforce’?

2. Inequality between artists’ incomes has increased in recent years; what would it take to politicise these excluded artists? And what action might it lead to?

3. Is self-organisation an effective counter to the ‘exclusionary mechanisms of the art market’?18

Sholette has no answers to these questions and only comes to the conclusion that ‘artists gain improved social legitimacy within the neoliberal economy while capital gains a profitable cultural paradigm in which to promote a new work ethic of creativity and personal risk taking.’19 Artists currently voluntarily contribute to the symbolic system, even though they must be aware that, in most cases, it guarantees their own ‘failure’.20 Later, he calls this a ‘managed system of political underdevelopment’.21

Group Stigma

His survey of artists’ groups leads him to draw two conclusions. Firstly, in spite of the efforts of the management theorists, there is still an art world stigma against ‘multiple authorship’, or presenting as a collective or group, although this is decreasing. This stigma may be mainly due to group membership usually being in flux; regular self-terminations happen for all kinds of reasons including internal disputes, resignations of key members, or even commercial success. Sholette’s survey shows that groups are (or appear to be) marginal players in the art world.22 Secondly, in the 1960s and 1970s groups were taking on organisational forms that mirrored the structure of the organisations that provided them with financial support. This has shifted since the 1980s and there is now less interest in organisational conformity:

Perfunctory compliance with official cultural regulators may have been a sporadic though unspoken practice by artist groups in the past, but today in an age of deregulation and semiotic warfare, such tactics are becoming pervasive, even amongst groups who, at least on paper, appear to be commercial enterprises.23

This is a mildly encouraging sign, but, due to the lack of ontological refinement of the differences between types of artists’ groups, Sholette’s conclusions about the nature of collectives as typical dark matter seem weak. In particular, there is no distinction drawn between a group of two or three people working together and larger, open collectives with internally democratic structures.

In terms of defining collectives as more or less autonomous, more or less radical, and more or less dark matter, the two most important things, as far as I am concerned, are these: the extent to which the collective is permeable to oral culture and working class people and the extent of independence it can maintain from commercial and state run institutions. Several of the larger collectives in my experience had an open door to new members – the currency of membership was the labour put into the project. They also had a clear no selection policy when it came to what work was shown. ‘NO STARS, NO SELECTION, NO TASTE’ was one Exploding Cinema slogan. Brixton Artists Collective 1983-86 decided upon shows at open public meetings. Membership was open to all for a few pounds. Both these collectives had a certain style in their spaces that was orientated towards the general public rather than an elite art audience. This kind of thing is anathema to the art world, where selection and the creation of exclusivity and the celebration of the possession of elite skills and knowledge is their raison d'être.24

Conclusions

What is really needed in this book is a class conscious theory of how culture works. The use of the categories ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ is unsatisfyingly vague. I’d prefer to use the historical separation of literary culture from oral culture (in Europe) as the dynamic that drives dark matter away from the light of publicity. This could help bring some clarity to the question of class.

I’m using ‘oral culture’ here in a quite specific way, one which I’ve been reminded by Mute editors is not yet in common parlance. The meaning I like to inflect oral culture with is a global one that encompasses all the processes by which we come to agreements on meanings, or by which we beg to differ, from time immemorial. As the zone of direct and relatively unmediated communications, oral culture is the main forge of human language and I don’t believe, for instance, that Shakespeare invented the word ‘bubbles’. Oral culture is the seat of judgement for the plethora of meanings that soak our environment. Oral culture is the pool in which all the sense media of our communication thrive.25 Any new meanings have to be taken on within these fluid and common spaces of communication. Just like the production of goods, the production of cultural meanings depends on the multitude.

Literary culture is of relatively recent origin, and, from where I sit, expresses a localised European geography that can be traced back a thousand years to the humanist break from the writings of the Christian monks, using their discovery of Arabic translations of the ancient classics (and particularly Aristotle). This formation, embedded in the early city states, received a tremendous boost with the invention of printing with moveable type in 1450. The whole publishing apparatus became a means to power for the new bourgeois class who usurped the publicity of the aristocratic spectacle with their own literary discourses and knowledge.26 Literary culture became closely identified with bourgeois being. They still hold on to it as their birthright. The bourgeoisie tries desperately to control meanings and communication, to police oral culture, to put us each in a mind cage. But this domination is ultimately an illusion. The meanings we hold in common are, at the end of the day, decided and reaffirmed in the oral realm. This means there is tremendous power in attending to it, and how to direct it.27

Sholette seems to veer from a passionate belief in the disturbing, if not revolutionary, power of dark matter: ‘self-organised dark matter inserting itself into the ripped fabric of neoliberal cities, from below’, to ambivalent feelings that perhaps these practices ‘subvert, and yet reinstate’. He seems unsure if these ‘emerging aesthetics of resistance’ are any more than ‘tepid acts of delinquency or even bitter gestures of discontent’. He hopes that they at least provide ‘an expectation’ – but of what?

This is really a diary or compilation of his efforts, thoughts and various involvements, and I think I had hoped for his own subjective engagements to be more explicit and less academicised. The reason for this focus on a very particular stratum of dark matter would then be more organic and less arbitrary. A global study of dark matter would take the kind of team effort and resources that go into compiling a major dictionary or encyclopaedia. The key question may be how any such institution could maintain its revolutionary integrity and class consciousness whilst carrying out such a task.

Sholette has invented a useful term that might well be taken up, and gives us a sporadic view of resistance through political art, but his style of authorship in Dark Matter is too conventional. I feel the style on the whole mutes his own analysis to occasional whispers, rather than making oppression and its exclusions the key definer of the ‘from below’ of cultural production. Cultural resistance is no new thing.28

Sholette thinks that ‘dark matter is getting brighter.’29 This may simply be a function of media technologies making all kinds of knowledge more visible, or it may signify a huge groundswell of demand for more democratic societies. Or, perhaps, these are two sides of the will to power in the oral realm, the struggle from below. This book certainly allows us to give a name to, and begin to focus on, the creativity and cultural resistance that exists outside the art world proper. It may be flawed and partial, but it represents a good start towards developing a discourse that I think needs to embed itself outside of the academy – within the fields of dark matter itself.

Stefan Szczelkun <szczels@ukonline.co.uk> is an artist, living in South London, with an interest in open artists’ collectives and networks

Info

Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, London: Pluto Press, 2011.

Links to Greg Sholette’s strata of dark matter:

Candida Television: http://candida.omweb.org/

Journal of Aesthetics and Protest: http://www.joaap.org/ 6+: http://www.6plus.org/borcila.html

Howling Mob Society http://www.howlingmobsociety.org/

Critical Spatial Practice: http://criticalspatialpractice.blogspot.com/

MicroRevolt: http://orangeworks.blogspot.com/

Center for Tactical Magic: http://www.tacticalmagic.org/

Yomango!: http://yomango.net/ and http://www.yomangoteam.com/

The Yes Men: http://theyesmen.org/

Critical Art Ensemble http://www.critical-art.net/

Target Autonopop: http://www.targetautonopop.org/

Temporary Services: http://temporaryservices.org/ including their wonderful Public Phenomenon Archive see also http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/?page_id=21

Footnotes

1 Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, London: Pluto Press, 2011, p.99.

2 Ibid, p.100.

3 Ibid, p.11.

4 Ibid, p.34.

5 There are of course always exceptions to what is accepted. It can come down to personalities. When Simon Ford worked at the National Art Library he bought in a load of scurrilous zines and mail art. He never seemed intimidated by the institution whatsoever. Further back, Meg Duff at the Tate Library was very approachable and openminded, which might have been due largely to the liberal left support of ARLIS, a very well organised art librarians’ union, which both Simon and Meg were leading members of.

6 Ibid, p.40, p.185, p.186 and p.188.

7 The original materials I collected are held in the BFI Special Collections and at http://www.stefan-szczelkun.org.uk/index2.htm

8 The alternative to the Tate’s Archive is Andrew Hurman’s self-funded and panoramic web archive of Brixton Gallery 1983–86. http://www.brixton50.org

9 Sholette, op. cit., p.30.

10 Ibid, p.145.

11 Sholette, op. cit., p.168. Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Conversation in Modern Art, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. See also his The One and the Many: Agency and Identity in Contemporary Art, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

12 Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere, 1993, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. This was a response to the perceived elitism or at least limitations of Jürgen Habermas’ notion of the public sphere. Habermas does indeed privilege the literary over sense media in what I have read of his work. See footnote 20 below and Jürgen Harbemas, Theory of Communicative Action, 1981. The quote is from Negt and Kluge, ibid, p.188.

13 Ibid, p.3.

14 Ibid, p.44 and p.122.

15 For a classic exploration of art as collective action see, Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

16 Carol Duncan, ‘Who Rules the Art World?’ in Aesthetics of Power: Essays in Critical Art History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983, p.172.

17 Sholette, op. cit., p.126

18 Ibid, p.116.

19 Ibid, p.117. Dark Matter is good on how creativity and collaboration have become part of the new liberal management speak from Tom Peters to John Howkins. Artists who work collectively are seen by these people to have powerful problem solving skills, in contrast to the individualistic way in which art discourses have previously upheld genius and feared collective authorship. Perversely, it is by these business theorists that the idea that culture is inherently collective is being most successfully promoted.

20 I’d prefer a blunt talk about artist’s oppression. See my self-published pamphlet ‘Artists Liberation’, 1986.

21 Sholette, op. cit., p.120.

22 Something that is very different in other media such as music and theatre.

23 Sholette, op. cit., p.163.

24 An 18-minute long oral history documentary on Brixton Artists Collective is available on DVD from 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning as part of it Brixton Calling! Archive show 29 October to 17 December 2011.

25 Let’s not get distracted by things like all the working class people in literary studies, or, more widely, all those commoners who have gone through university in the last 40 years, or even by the achievement of mass literacy in the last century. Let’s not be confused by the oral aspects of bourgeois culture. This is a theoretical idea somewhat like the distinction between lifeworld and system.

26 This history can be followed in Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, Cambridge: Polity (1962 trans. 1989) and can be read alongside Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: the impact of Printing 1450 - 1800, translated by David Gerard, London: New Left Books, 1976.

27 I might owe a debt here to Hannah Arendt’s idea of power. I have to admit to reading Arendt indirectly, through e.g. Jonathan Schell, The Unconquerable World: Power, Nonviolence, and the Will of the People, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2003. http://stefan-szczelkun.blogspot.com/2010_02

28 E.P. Thompson’s Customs in Common and work on the construction of ‘folk’ music by people like Dave Harker and Bob Pegg in the 1980s, showed that cultural resistance was always a response to the imposition of power. Another heroic effort, within a very different stratum of dark matter in view, was made by Emmanuel Cooper in People’s Art: Working Class Art from 1750 to the Present Day, Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1994. We could even trace the idea back to Jean Dubuffet’s use of the term Art Brut, or ‘Outsider Art’, as it came to be known in the English speaking world thanks to Roger Cardinal’s work of 1972. See, Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art, London: Studio Vista and New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972.

29 Sholette, op. cit., p.3.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com