Click Here for Epiphany

Tom McCarthy on Russell Hoban

Whatever their differences, literature and science have in common one central preoccupation: gnosis, that movement — at times mystical, at others rigorous and empirical — towards revelation, understanding. The desperate need of Kafka’s heroes to get to the truth behind the bureaucratic veil, or Conrad and James’s characters’ slow pilgrimages to the centres of various hermeneutic labyrinths, or George Eliot’s Casaubon’s painstaking scouring of Europe’s libraries in search of "the key to all mythologies", or Sophocles’s pitting of Oedipus’s wits against the Sphinx so he can lift the curse on Thebes by solving her riddle — don’t these find their exact correlatives in the Genome and Enigma projects, in the quest to find a cure for cancer? The correspondence here isn’t coincidental. Three and a half centuries before C. P. Snow could talk of ‘two cultures’, Francis Bacon, laying the very grounds for modern science by upgrading mediaeval alchemy so it could run alongside more recent systems such as Renaissance poetry, presented the new discipline’s object of inquiry, the natural world, as God’s ‘Second Book’.

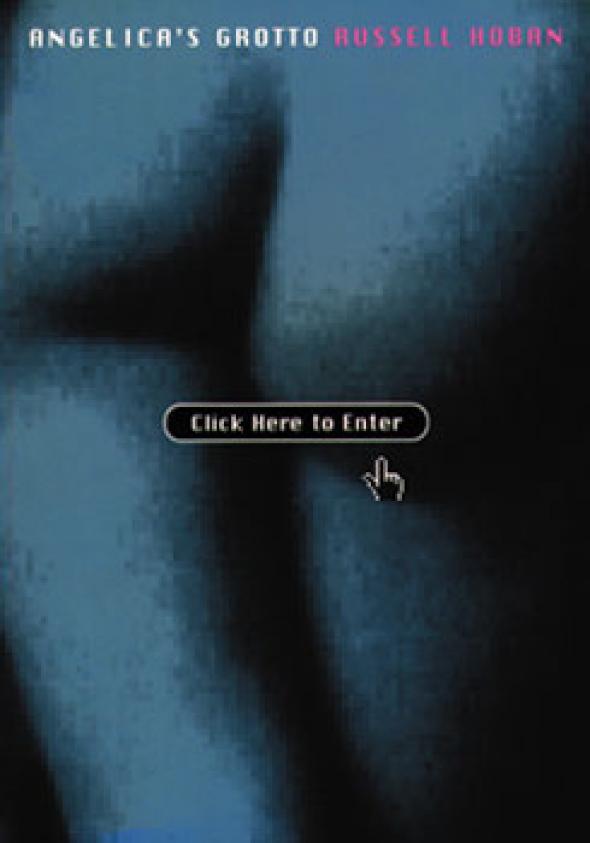

Nowhere, perhaps, is the gnostic tendency in literature more apparent than in writers who deal with the Puritan sensibility — or, to give it its modern title, Paranoia. From DeLillo and Pynchon right back to Andrew Marvell (and, incidentally, if you want to really understand Pynchon, read Upon Appleton House), these authors’ work is characterised by encryption and its reversal, by psycho-detective protagonists chiselling away at overdetermined rockfaces. But if you find the task of chiselling away beside them too demanding of encyclopaedic resources and time, then you could do worse than check out Russell Hoban. Thoroughly accessible and reader-friendly, his books deal with precisely the need to ‘read’ and decode phenomena. In his most famous novel, Riddley Walker, the very stones and woods and animals, not to mention the quasi-religious puppet shows the characters perform for one another, are shot through with ‘blipful’ meaning, with ‘connexions’ and ‘reveals’ and ‘tarpritations’. Riddley Walker is a post-apocalyptic fable (whence its half-decayed vocabulary); Hoban’s new book, Angelica’s Grotto, set at the very end of the second millenium, in a world in which politicians gag on oranges and women’s underwear while ravaging the environment, could perhaps — and in true Puritan fashion — be termed pre-apocalyptic.

Hoban’s hero, Harold Klein, is a seventy-two year-old art historian who, having lost the voice that lives inside all of our heads, honing and censoring our traffic with the external world, seeks enlightenment and cure first in a psychoanalyst named De Vere (‘Of Truth’: for the paranoid mind, names are never insignificant) and then in an eponymous — and pornographic — website. It’s tempting to put a Lacanian gloss on what ensues: robbed of two crucial tools of the symbolic order, both equally enabling and interdictive — a silencing inner tongue and the phallus (Klein can no longer get his up) — he uses his outer tongue for repeated cunnilingus with the website’s owner, Melissa Bottomley, a lecturer in the Politics of Language at King’s, after obtaining her name by bribing Lester, a black porn-star with a big cock and bad attitude (Updike’s Skeeter without the political conscience), to reveal it. But Hoban’s layout resists pat schematising: it’s complex, protean, fluid, full of colourful allegorical objects (mainly artworks: Redons, Klimts, Daumiers) that pop up to be interpreted, then, stripped of metaphorical status, are repurposed as plot drivers or, in the case of a Meissen statuette, the proverbial Chekhovian gun.

In Riddley Walker, technology is what has been lost. In Angelica’s Grotto, by contrast, it’s enveloping, facilitating. Klein, searching no less intently than Riddley for connexions and reveals, is what the French call branché, plugged in — to everything: his ISP, his video collection, tubes administering drugs whose names are reeled off in long lists. Technology’s supreme manifestation, the Internet, figures as mankind’s collective memory-bank (in Hoban’s children’s classic How Tom Beat Captain Najork and his Hired Sportsmen this role is played, surreally, by the Nautical Almanac). But if Klein acts like Beckett’s utterly tech-record dependent Krapp, hugging his tape recorder to him, poring through old indexes, he also enacts Krapp’s pastoral side, reminiscing beautifully about walking dogs through childhood woods, about swimming in water that was deep and green and cold. This is science in its true, etymological sense: knowing, memory, like in Proust. Klein the gnostic scientist I-Chings everything: Trafalgar Square, The Strand, passers by, busses. That it’s one of these that finally does for him isn’t just a convenient deus ex machina ‘out’, as is the underground train accident that rounds off Hoban’s last book, Mr. Rinyo-Clacton’s Offer. It’s more than that, almost transcendental, a union with the plane of his enquiry, with the veil. The final answer, it transpires, is ‘fourteen’ — or, if you like, ‘Elmer’s End’.

Tom McCarthy <tom AT envoi.demon.co.uk>

Angelica’s Grotto by Russell Hoban, Bloomsbury, pp271, £9.99.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com