Captives of Combination

In this double review of exhibitions by Camille Henrot and Hannah Höch on display in East London galleries this spring, Josephine Berry Slater sees how differently the art of combination can be plied by artists working a century apart

In the last month East London has seen two shows by female artists that work to illuminate each other and our present moment quite interestingly: ‘rising French art star’ Camille Henrot’s show, The Pale Fox, at the Chisenhale Gallery and German Dadaist Hannah Höch’s retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery bear some comparison. Both artists’ work deals with the power of technological reproduction (internet and print respectively) to circulate information and images of natural and cultural objects at profoundly transformative scales within their own epochs. However, their responses to the resulting social and epistemic shocks reveal vast differences in the forms and strategies of art as it engages techno-capitalism at an interval of nearly a century.

From 1916 onward, Höch worked as a pattern designer for the Ullstein Verlag and its popular women’s magazines in Berlin, and was thus unusually well placed to cull multiple copies of photographic images from their pages. Her work intensified the cultural and psychic uncanniness of print media’s creation of ontological collisions and cuts, through the close arrangement of photographic images of people, animals, sites and objects usually separated by vast scales and distances. The strange visual proximities, frames and cleavages thrown up by illustrated magazines were intensified by Höch’s technique, putting pressure on the fault-lines of her contemporary moment and drawing them out into new transgressive unities.

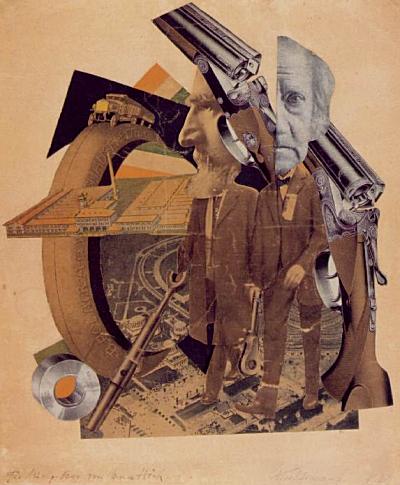

Image: Hannah Höch, High Finance, 1923

Henrot’s work takes place in a time in which we have apparently grown accustomed to these collisions and splices, though less so their speed and quantity within digital networks. Her film, Grosse Fatigue (2013), which won the Venice Biennale’s Silver Lion prize, drew upon a torrent of images unleashed from a multitude of life worlds (from zoology to nail polish), edited in sync with the beat of a rap song which mixed origin narratives in a trans-cultural stream of consciousness.[1] In The Pale Fox she takes a different tack, laying out these worlds of images and objects three dimensionally into interlocking eddies of thematic or conceptual association. This creates a new spin on the ‘epistemic panic’ caused by digital acceleration and ontological relativity that her work registers and inhabits. This panic can be read as extending beyond the mere feeling of information overload, as the digital starts visibly reordering our physical reality (the 3D printer being just an extreme case of the blending of informational and physical spaces), or as all our experiences become digitally mediated by the systems we have internalised. That in 2013 more photographs were taken than in the entire history of photography registers the degree to which our reflexive experience has become integrated with technological assemblages of cameras, computers and telephones.

Both artists, working with the cutting-edge techniques and forms of their times, meditate on the social and natural upheavals required to bring into being the extensiveness, even globality, of the knowledge systems they participate in. Speaking of the famous collection where she undertook an artist’s residency in 2013, Henrot concludes:

the Smithsonian was built on the destruction of a very rich culture. When the Indians were still being massacred and expelled from their land into reservations the second director of the museum sent a lot of people to gather objects and record ritual and so on because he knew this culture was disappearing. At the same time as there was destruction there was also the recording and accumulation of objects in the museum.

But does this insight really produce much more than that desired kink of self-reflexivity upon which the production of the same feeds? Such an institutionalisation of critique was famously characterised by Damian Hirst whose oeuvre was apparently an exposé of the violence which founds the western mode of vision (dead animals suspended in glass vitrines) but who effortlessly converted it, via its art value, into a profit/exploitation machine.[2] Henrot’s work considers the planetary destruction our knowledge system reaps, but in a register as cool as the science it invokes. This is what produces its sublime and beautiful qualities, whilst smoothing the way to its institutional digestibility. When we compare this to the work of an artist like Harry Sanderson who has traced the chains of global exploitation (both of humans and nature) upon which our embarrassment of high res digital images rests, Henrot’s cool complacency becomes palpable.[3]

Image: Camille Henrot, The Pale Fox, The Chisenhale Gallery, 2014

Hannah Höch’s work likewise registers an earlier moment in the development of industrial capitalism and the associated colonial violence on which the western episteme gorges itself. In a way that forecasts Bruno Latour’s exposé of modernity – that in trying to create a pure space of human (metropolitan) culture, rational agency and linear progress, modernity has proliferated nature/culture hybrids beyond its worst nightmares, which it can no longer repress – Höch’s Dadaism lampoons the western dream of purity through her generation of a bestiary of photomontaged hybrids. Working under the atmosphere of nationalist and eugenic thinking that raged in Germany in the 1930s, Höch photographed many objects from the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin, which she then spliced with images of glamour girls, men in Prussian uniforms or bourgeois dress, and the powerful athletic figures of New Men and Women that populated modern and totalitarian imaginaries of all hues at this time. If socialist realists and populist magazines alike promoted images of athletic and energised bodies as the components of modernity’s newly invigorated social machines, these bodies were nevertheless individual and complete. By contrast Höch, along with Siegried Kracauer and other radical avant-gardists, embraced the artificiality of capitalist modernity’s severing and reintegration of the individual body into the co-ordinated sequences of mass production, but used this violent dismemberment to imagine collective forms of subjecthood ‘freed from the burden of race, genealogy, and origin’, not to mention gender and individual identity.[4]

In The Big Step, 1931, an image of almost cute simplicity, the diagonal thrust of a male dancer’s striding and winged legs, is met not by the well-toned torso we expect, but by a monkey’s head. The prancing, classical legs are piloted by a primate mind, watched over by the indulgent smile of an angel assemblage, half show girl, half African carving. This bathetic image works by placing the western fantasy of civilisation on a par with animals and ‘primitive’ art. In other collages, such as Peasant Couple (1931) or Love in the Bush, (1925), black, white, male, female, human, animal, doll and living bodies are combined in ways that must have scandalised the ‘stuffed-shirt bourgeoisie’ of the time. But for Höch, one of the inventors (along with other Berlin Dadaists) and all time masters of photomontage, it was as much a way to create new synthetic beings, as taboo couplings. For Höch, photomontage helped lend fantasy a reality effect: ‘the Dada photomonteur set out to give to something entirely unreal all the appearances of something real that had actually been photographed.’[5] In creating these minor realist frissons in which, say, the image of a father cradling a baby is found to have the exquisite arms, legs and feet of a woman, (The Father, 1920), not only is a certain power relation or hermeneutic system exposed, but the development of a new being, or way of life, is also glimpsed. The father, here, is surrounded by cut-out photos of more New Men and Women; leaping dancers and boxers who stride or strike towards or away from the central couple. But the energy they embody doesn’t amount to much because it doesn’t meet and intersect with a counter-force or its opposite. By contrast, the central image of the ‘father’ is both absurd and serious, or absurdly serious, in its imperfect synthesis of the male and female sex. A thinking (male/head) yet sensuous (female/body) being is born, but within an image that simultaneously elides and exposes the differences and joins of its component parts in a constant oscillation.

Image: Hannah Höch, Love in the Bush, 1925

In an interview text that accompanies her show, Camille Henrot also expresses the importance of this tension: ‘Synthesis’ she says, ‘is never really interesting, it’s almost like a bourgeois solution. It’s the dynamic between thesis and antithesis that is interesting.’ Yet the disappointment of her work is that far from manifesting the tension she advocates, it choreographs endless ripples of hermeneutic différance.[6] I imperfectly noted down some of the flows of objects and images I encountered along the south facing wall, on entering the room-sized installation, as follows: sleep mask and photo of white fox, Arp-like sculptures, an aluminium steel ramp jutting forward onto which blank pieces of paper are slotted upright, like the exploded download history in the Mac OSX dock, The World Book encyclopaedia stacked up along an aluminium shelf on the wall, empty Muji photo frames, a photo of the US moon landing at the ‘Descartes Landing Site’, the words ‘Hubble’s Improved Vision Reveals’, a series of empty Apple product boxes (Mac Time Capsule Hard Drive, USB SuperDrive, MacBook Air), illuminated angle-poise mounted magnifying glass, photo of stone feet of a Hindu (?) God, photo of flames on water, painted calligraphic gestures framed by pictures of a Pacific Horked Frog, a CD titled ‘Quantum subliminal entertainment network’.

If Höch pre-empts Latour’s diagnosis of modernity, then Henrot seems to carry out his strategic response. Moving around The Pale Fox installation feels like being dropped into a virtual tour of one of his actor-networks – a concatenation of beings, phenomena and objects positioned neither as nature nor as culture, but as ‘nature-culture’, in which we abandon those old ‘great divides’ between humans and non-humans, science and culture, West and the Rest, etc. that sustained the fantasy of ‘modernity’.[7] Now that we know we are ‘non-moderns’, there is no privileged site of knowledge, and no double standards applied to different ways of relating culture to nature. We no longer bear science up our sleeves as the trump card of truth, while patronising the animism of other cultures. This Latourian perspective seems to lie behind Henrot’s even-handed proliferation of both scientific extensions of vision (the telescope, the microscope, the photograph, the computer) and cultural ones (the photo frames, the inclusion of plausible art gestures such as surrealistic bronze sculptures or calligraphic squiggles, the liberal use of iPads as means of display, the highlighting of file structures and browser windows). These ways of seeing are let loose to mutually condition and limit one another.

The risk of proliferating ways of seeing without prioritising any, however, is that we lose all perspective, and lapse into toothless postmodern relativism. If Henrot’s work courts this sense of disorientation, it does so whilst maintaining a focus on the digital means of production that underlie the heady escalation of information and knowledge systems. The ground of all this différance becomes the solubility of everything, objecthood included, within the ‘universal machine’, the computer. The installation ties all its part-objects together by way of an enveloping IBM ‘screen of death’ blue background – both walls and carpet – as well as an immersive, acoustic electronic drone. These seem to signify an all subsuming digitality whose smooth path to transcendence is nevertheless fissured by breaks and contingency: the drone sound is occasionally interrupted by recorded coughs, and the calm blue carpet is traversed by the aleatory movements of a battery-operated snake who ‘mysteriously’ never quite bumps into anything or anyone.

The sense of an underlying informational infinity, which leads to an endless regress of knowledge systems without the finality of truth, is tracked to the digital at so many junctures that all other objects present cannot but be implicated by it, even if they precede the digital age. But its cipher, the surround-wrap IBM Blue, is in fact nearly indistinguishable from Yves Klein Blue; a proximity that places the empty infinity of automatic process alongside the sublime infinity of transcendence (‘Leap into the Void!’). If the tension Henrot desires exists in her work, it is in the way it positions itself between these two states: longing for art’s transcendence (wisdom, world knowledge, beauty, transformation), whilst obsessively drawing attention to the ambient conditions of undecidability and the emptiness of modernity’s productive processes. In this respect, the ‘artness’ signified by some of the objects – the conspicuous calligraphic gestures and bronze surrealistic sculptures threaded through the installation – represents the struggle for singularity within a regime of blind (machinic/informatic) process. Of course the really singularising gesture can only reside at the level of the installation as a whole, or rather it is here that we must judge it.

Image: Camille Henrot, The Pale Fox, The Chisenhale Gallery, 2014

Untroubled by the angst of the indifference born of différance, Höch’s work instead turns the tools of industrial repetition back upon themselves in a clear gesture of negation. This is articulated most politically in her Dada period, and is probably epitomised in High Finance, a photomontage that splits open the heads of two industrial capitalists with the barrel of a gun, as they step over a landscape of alienating rationality, gesturing towards it with their large keys of ownership. The mechanical instrument of death is turned upon those who wield industrial machinery as a living-death sentence for the majority. In later life, however, the lessening of her work’s antagonistic charge can be seen in a series of collages from the 1950s based on the space race. Where she might have inserted her ‘kitchen knife’ into the erectile dysfunction of world powers facing off by sending peopled metal tubes into space, she instead created a series of dream-like collages entailing plant-machine hybrids traversing unknown worlds. Space Travel (1956) superimposes a dense bundle of floating tubes onto a background of rephotographed, fuzzy newsprint – information blurs out into cosmic accumulation. Moonfish, from the same year, confuses the moon and sky with the sea, as well as fish with the nude form of a woman. But if not directly satirised, imperialism and capitalism are nevertheless suspended from imposing their techno-natural destiny upon us, in a way reminiscent of The Father’s rejection of sexual destiny. Instead Höch feels out disallowed junctions and new unities, here between the desire for space exploration and the fish’s will to wiggle through water, the beauty of plants and the autopoiesis of machines.

Höch doesn’t offer art as a fantastical escape capsule from the unendurable conditions of society, but as a way of examining the hidden and taboo relations that, uncovered, suggest new forms of life and living. By contrast Henrot, whose exhibition title, The Pale Fox, is derived from an anthropological study of the cosmogony of a West African tribe, is conspicuously reticent about art’s own powers of genesis. This is revealed by the fact that her myriad combination of things never produces ruptures or any actual sense of transgression, but only a sometimes euphoric feeling of kaleidoscopic play. Where Höch is undaunted in her quest to hijack regimes of repetition and death and flip them into the spark of new imaginaries, Henrot obsesses over origins, whilst denying the possibility of the new. Her work is undoubtedly a symptom of a society in which digital capitalism produces a cornucopia of goods, knowledges, processes, images and tools, but leaves us at a loss as to how to operate them. If there is a rare beauty and energy in her ability to conjure the depth and scale of informatic abundance, one wonders whether a dose of Dadaist antithesis and synthesis might not help expose the social and material reduction our digital abundance blots out.

Josephine Berry Slater <josie AT metamute.org> is an editor of Mute, and teaches on the Culture Industry MA at the Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths College

Info

Hannah Höch is at the Whitechapel Gallery 15 January 2014 – 23 March 2014

http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/hannah-hch

Camille Henrot’s The Pale Fox is at the Chisenhale Gallery 28 February – 13 April 2014

http://www.chisenhale.org.uk/exhibitions/current_e...

Footnotes

[1] For a short film about Grosse Fatigue, see http://vimeo.com/86174818

[2] Thanks to Anthony Iles for this example.

[3] See Harry Sanderson’s ‘Human Resolution’, Mute, April 2013, http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/human-r...

[4] See Hito Steyerl, ‘Cut! Reproduction and Recombination’, in The Wretched of the Screen, Sternberg Press 2012, p.181; and Siegried Kracauer, ‘The Mass Ornament’ in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, Thomas Y. Levin (trans.), Harvard University Press, 1995.

[5] Hannah Höch, ‘Interview Between Edouard Roditi and Hannah Höch’, in Hannah Höch, Prestel Verlag and Whitechapel Gallery, 2014, p.187.

[6] This is Derrida’s term to describe the movement of meaning both as an effect of the signifier’s difference from others, but also as something endlessly deferred by the sign’s inability to summon forth a definitive meaning.

[7] Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, Catherine Porter (Trans.), [1991], 1993, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com