Barbara Says — Industry Does it Faster

Buy on Amazon UK £9.99 and other regions, Super Saving free shipping.

As the financial crisis fastens its grip ever tighter around the means of human and natural survival, the age of the algorithm has hit full stride. This phase-shift has been a long time coming of course, and was undoubtedly as much a cause of the crisis as its effect, with self-propelling algorithmic power replacing human labour and judgement and creating event fields far below the threshold of human perception and responsiveness.

A meticulously curated survey show of the Artist Placement Group at Raven Row gallery provides scope for a nuanced understanding of the unusual relationship they brokered between bureaucracy and art; one that rejects glib notions of collaboration in both fields. Review by Roman Vasseur

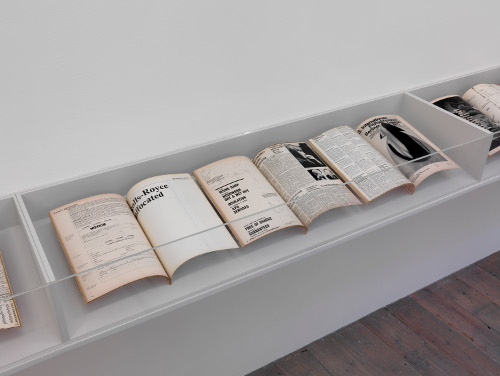

In the luxuriously long cabinet gracing the wall of Raven Row Gallery that features the eight inserts completed for Studio International by Artist Placement Group (APG) in May 1970, a picture of Barbara Steveni in glamorous profile is captioned ‘Barbara Says – Industry does it quicker’. Between visits I’d remembered the caption as ‘faster’ not ‘quicker’. Further into the show a recording of Steveni’s breathless Dictaphone notes for APG unnerves through its lack of irony and urgent embodiment of management speak. That APG’s over-identification with industry and government’s management rituals should stand out at Raven Row suggests the possibilities for current practices that this considered and carefully curated show offers up. In so doing it manages to narrowly avoid what might have ended in a lament both for the audacity of APG’s approach and the politics of the period in which they formed. Reading the organisation’s time-line in the accompanying publication it becomes clear that the pairing of APG’s blood lines with its aristocratic host’s in the form of Raven Row Gallery throws into relief the performative roots of APG’s inception and its private political life. A survey show at a public museum concerned with the measurable social impact of its work might have obscured the questions raised in this exhibition as to how art pictures itself ‘doing power’ through performative and quasi-situationist approaches. The Studio International caption acts as a piece of détournement, framing APG’s relationship to the passions of production as post-Fordist — underscoring its desire and its contradiction to be accepted by industry and government whilst retaining its autonomy as art.

Both past and present critiques of APG have produced a gap between the symbolic and ethical outcomes of the project, from which tragedy has arisen as the dominant ground for discussing the effect and /or affect of their work. The question remains over whether they effected real social change or figured as dandies too naive to understand the politics and economics of the hosts they courted? This exhibition’s narrative partially denies casting the APG project as a tragic struggle against power that would have inscribed their legacy into the tablet of history as an act of heroic alterity. Instead it suggests how – and particularly in the case of John Latham’s approach – theirs was an audacious demand for an extended, even cosmological time-frame within which to imagine the artwork’s unfolding, thereby altering an understanding of the technocratic forms of governance APG appeared to ape, hollow out and occupy. Much of APG’s work can be summarised in a catalogue, or a lecture or online but it is the fragments of language displayed in the documents and ephemera that countered the expectation of an informational exposition that would have presented theirs as a purely dialogical set of practices. What begins to appear is both absurdist and metaphysical in its relationship to power.

Image: Selected issues of Studio International, 1970 – 71. Courtesy Henry Moore Institute and Jo Melvin. Photo: Marcus J. Leith

In Art Power Boris Groys speaks of the way in which business, due to its increased aestheticisation, has moved towards art and therefore into a space that can be critiqued as art. If our present is a time where ‘the meeting’ has become the site and image of collaboration and productivity, then APG’s fetishisation of the meeting place as ‘The Sculpture’ for its residency of the Städtische Kunsthalle, Dusseldorf in 1971, was a premonition of a current reality where management’s claims of utility exist in excess of utility itself. The contemporary image of the meeting serves to display and construct connectivity as value and as a means of obscuring capital’s losses and speculative work. In contrast, for APG the meeting remains excess but also a form of explicit role-playing that explores executive decision making in opposition to the collaborative act. Latham was very clear that the term ‘collaboration’ would not define APG’s activities. This leads to both a sense of discomfort and nostalgia that arises from looking at the material and time-lines in the show – a desire to see a time when centres of power were more clearly identifiable and less consultative.

Steveni and Latham in their 2003 interview with Mute suggested that the opaqueness of their own terminology was what made it possible to maintain the uniqueness of APG’s mission – that the project was in effect a turn of language tied to an idea of ‘event structure’ that ignored technocratic and political time-frames. In addition to the term ‘incidental person’ was that of the ‘disappearing artist’. A term only partially developed by Stuart Brisley and John Latham for the 1968 Industrial Negative Symposium. The term returned fleetingly in the panel discussion held at Raven Row, UK Industry in Transition 1966–79; APG from the Corporation's Perspective, in connection with artist Roger Coward’s assignment to Birmingham City Council on the council’s urban renewal programme. Coward’s embededness in the processes he developed suggested a hypothetical conclusion to the project in which he finds himself many years later holding down a permanent post with Birmingham City Council. He has become an active resident and member of the community that was originally the subject of his placement and has forgotten he was sent there as an artist. Ideally this future scenario would extend to a time when Coward, the ‘disappeared artist’ becomes the focus of an artist led consultancy in the burgeoning culture of art and regeneration schemes of the late ’90s and early ’00s. The ending of this fiction sees the embedded artist design counter-consultancy strategies at which point his memory is restored and he returns to London seeking his former life and an identity that’s been destroyed.

That the placements threatened disappearance – and for some artists caused a crisis in their studio production, gallery and museum careers – demonstrates how the time-frame Latham proposed would uncouple artists from their own subjective rituals. The ‘open brief’ (APG’s manifesto for working with institutions) produced a subtext to many of the placements overtly stated objectives. This included encounters that were often unrecorded, informal, private, clandestine and absurdist. There were clearly quantifiable effects both within and outside contractual arrangements, including Ian Breakwell’s work with Broadmoor and Rampton high security psychiatric hospitals where Breakwell managed to find a means of making public otherwise embargoed observations through his own artworks, which later fed into a two part TV documentary on high security hospitals. That Breakwell found other ways of disseminating his work outside the period of the placement points to a commonly experienced problem for many public art projects, even those that appear to have a clear objective but then atomise as the process of fulfilling the brief unfurls a series of parasitic interests, organisational structures and procedures. As an artist, how do you capture the collateral that arises from the nervous breakdown of a project? Or do you let this collateral of reactions and narratives work atavistically without your continued authorship or expectation of a return on your energies? In these circumstances questions arises of how to define, if at all, what the work is and where and when meaning takes place? Questions of how to locate ‘the work’ are endlessly prompted by documents in the Raven Row exhibition and the accompanying discussions. For example, the letters stemming from the placement of artist George Levantis with Ocean Fleets Ltd between 1974-75 takes on a tragicomic turn that could be called ‘the work’. Levantis attempted to act as a listening ear to members of the crew on the cargo ship’s voyages to Africa and Asia, in the process he designed and made for himself a mock naval uniform in order to be accepted as a member of the crew; caused grievances amongst some passengers and crew who were expecting art classes on one journey and subsequently suffered the indignity of having his temporary art constructions thrown overboard. These letters and the poster work by Latham advertising the sale of the Hayward Gallery combine situationist tactics with a form of power brokering – acting in the capacity of what Stuart Brisley called ‘a tightly knit, highly autocratic family business’. APG conducted its own curating in line with point three of its manifesto: ‘That the proper contribution of art to society is art’. Even when that art was business. That Steveni’s voice should have been so dominant at the sessions held at Raven Row is partly due to this fact —that the organisation’s management was also its curation.

APG continually re-digested its organisational framework, carefully considering its media representation. For example, by filming camera crews filming their meetings during their residency at the Städtische Kunsthalle Dusseldorf in 1971 a feedback loop was created between the language of its management and the placements; one that denied any space for a conventional commissioning agency to occupy, or a moderating role for the Arts Council to inhabit. That APG worked on behalf of the artist and the host organisation is significant in relation to recent historical public art commissioning that can artificially separate the interests of the artist and the host organisation. That APG was its own commissioning agency able to problematise its representation by mixing its chosen format of the corporate annual report with, as Steveni has said, the language of the Pirelli calendar and advertising, suggests that the group owes some debt to the work of the Independent Group and the curating of Lawrence Alloway. I am particularly thinking of the 1956 exhibition This is Tomorrow at the ICA. Where This is Tomorrow celebrated popular mass culture, technology and the display strategies of the trade fair, The Individual and the Organisation mined APG’s concern with the technologies of management. Peter Fuller’s historical criticism of the APG’s political and economic naivety, along with other voices at Raven Row events concerned with APG’s rush towards the boardroom door and not the shop floor, demonstrate discomfort with APG’s conjoining of executive power with art as opposed to a communal power that we assume to be the privilege and remit of critical art practices.

Image: Installation view, The Individual and the Organisation: Artist Placement Group 1966–79.

Photo: Marcus J. Leith

APG’s performative experiments in executive power act as a rebuttal to the apotheosis of collaboration in art and business, taking a severe modernist stance in self-appointing a select band of individuals to instigate, manage and carry out specialist roles. Steveni and Latham primarily made the decision that in order to have effect they would need to become an institution but be sovereign and so able to suspend and rewrite its laws whenever they and a close group of colleagues deemed it necessary for the maintenance of their objectives.1 It seems that this act of will was the only means by which to move away from an abstract set of principles and into a life situation. For this reason a large part of the project remains within a plane of formalism, which is modernity. Its approach suggests that forms of publicness and power are formed in small collectives, some times as art and sometimes as an opaque even occulted activity. The group’s imaginative occupation of bureaucratic procedures aided by close personal, political and intellectual interactions enabled it to instigate projects that leeched out psychic debris over many years, and continues to talk through its own excess to the excesses of our current utility.

Roman Vasseur <roman AT romanvasseur.com> is an artist living and working in London. He has exhibited at the ICA, Jeffrey Charles Gallery, Project Dublin, in Berlin and the USA. He acted as Lead Artist for Harlow New Town between 2008-2011 where he was asked to consider the art and architecture principles of the town’s original masterplan during a period of reassessment and regeneration. A forthcoming solo show for Cubitt Gallery, London opens in January 2013. Vasseur lectures in the UK and abroad including the School of Fine Arts, Kingston University, London.

Info

The Individual and the Organisation: Artist Placement Group 1966-79 is at Raven Row 27 September to 16 December 2012 http://www.ravenrow.org/current/

Footnotes

1 This reading of APG is derived from ‘Carl Schmitt in the Age of Post Politics’ by Slavoj Zizek in The Challenge of Carl Schmitt, Chantal Mouffe (ed.), Verso, 1999, p.18.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com