Four Fights

On 20 February, art school workers across Britain began an unprecedented fourteen days of strike action.The number of strike days is escalating each week; if the strike holds there will be very little art tuition nationally through the week starting 9 March.

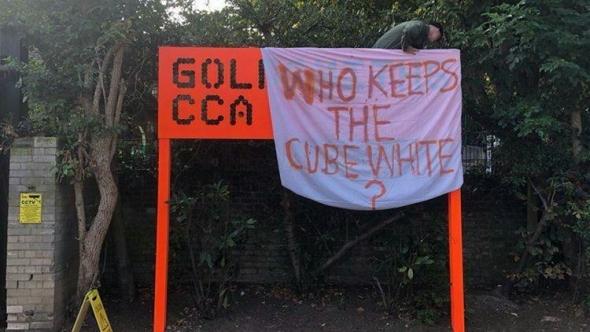

It is the first time in a generation that art school workers have engaged in ambitious, concerted strikes. The institutions involved include all of the University of the Arts London (UAL) colleges, the Royal College of Arts (RCA), the Courtauld Institute, the Slade, Goldsmiths, Brighton, and the Glasgow School of Art. Probably most workers are striking for the first time.

Organised through the University and College Union (UCU), the broad strike wave began in early 2018 against an attack on pre-’92 university workers’ pensions (the ‘USS campaign’). In later 2019 UCU began a second campaign, ‘the Four Fights’, involving both pre-’92 and post-’92 universities. Whilst the two campaigns are running concurrently – seventy four institutions are striking – the large majority of art schools are involved only in the latter.

The Four Fights campaign is against:

Falling pay: Since 2009, university pay has been effectively cut by nearly 20% in real terms.

Unpaid labour: On average staff perform two days of unpaid work every week.

Precarity: Casual contracts remain widespread.

And finally, both racist and sexist pay gaps: Women and black and minority ethnic staff experience significant pay discrimination.

Several of these issues appear to us particularly acute at art schools. One art lecturer tells us that, at UAL, ‘there are around 2500 hourly-paid Associate Lecturers (AL) and Visiting Practitioners (VP), who are employed to do most of the front-line teaching. Most of them are on fixed-term contracts for years, sometimes decades, with no promotion, no research funding, and risk of being offered fewer hours each year’. And not only UAL: in a 2016 UCU report, the RCA was shown to be the worst university nationally for contract insecurity. The Courtauld was 13th worst.

It is not only workers who suffer these contracts. As explained in the 2 March Open Letter to Students from Casualised Academics at UAL – signed by over 90 workers at the time of our writing – ‘casual contracts ultimately mean departments don’t work cohesively, staff members are stressed and overworked, and we don’t have the time we would like to build relationships with you [the students]’.

As to discrimination, according to the RCA’s own 2019 Equality Report ‘white applicants were almost twice as likely to be appointed to an RCA role than a BME applicant’. The same open letter criticises the both lack of BME people in senior roles at UAL colleges, and the racial and gender hierarchies of casualisation (‘28% of white male academics are on fixed-term contracts, whereas the figure for Asian female academics is 45%’) .

Moreover, art school’s self-reporting on equality hides a stark dividing of the workforce. As a Goldsmiths worker says, ‘the lowest paid people in these art schools are predominantly BME and migrants – the cleaning and security staff – that is, workers who don’t appear in the equalities statistics because they’ve been outsourced’.

How should art workers outside universities react to these strikes? What is our relationship to them?

First, a huge number of people currently working in the arts attended the schools now striking (and, of course, their international analogues). Those striking taught us, just as they’re now teaching the next generation of art workers.

Secondly, it is in these institutions that students not only learn to draw, or paint, or perform, but where they as future art workers first apprehend the art industry – first apprehend employment, ownership, and power in the arts. If my teacher had an insecure contract, shouldn’t I? If my tutor didn’t get parental pay, should I?

Thirdly, many UCU members themselves work for galleries, studios, biennales, publishers, art reviews, and the wider constellation of institutions that comprise the art industry. They are our immediate colleagues.

These are the direct, institutional connections. But, there is a more general similarity between labour in art schools and outside of them.

As art workers, the need for each of the Four Fights is immediately familiar to us. Our take-home pay decreases with inflation; we work for free, sometimes for years; we’re easily fired (or simply not re-hired); our management tends to be male and white, whilst our lowest paid colleagues are overwhelmingly BME.

Yet whilst the ‘labour aesthetic’ comes in and out of artistic fashion, and ‘political’ art is used to establish blue-chip artists’ and institutions’ ethical bona fides, the material facts of working in the arts – who, when, and for how much – remain embarrassingly gauche, if indeed they are considered at all. At worst, requests for written contracts or even payment result in dismissal; and the number of major employers in the arts presently engaging in collective pay negotiations with trade unions is vanishingly small.

This, despite the fact of vast profits being made (and laundered) through art, which is to say through the labour of art workers: not only artists, but also fabricators; not only fabricators, but also administrators; not simply administrators, but also cleaners – a series of workforces whose collective labour makes the creation of art possible.

‘Who Keeps the Cube White?’ is a question – several in fact – that has left the major arts institutions as yet untroubled, including every school mentioned above (except Goldsmiths). This is not due merely to managerial initiative or conscience, but rather since art workers and our unions are not sufficiently organised to answer, or even pose it.

According to the ONS’ 2018 trade union report, only 15% of workers in the ‘Arts, entertainment and recreation’ industry are trade union members, being 10% lower than the national average. The health, education, transport and energy industries have at least double the number of trade unionists relative to their size; the former two, triple the number.

Art school workers’ strikes are indeed ‘unprecedented’, showing a new strength amongst long-term weakness. A similar combination – of fledgling organisation in a largely non-organised industry – is revealed by the names below, a full third of whom are in branches that didn’t exist even a year ago (hence, some needing to sign anonymously).

Whether or not working conditions in the art industry worsen further – with art itself coarsening as the industry becomes still more by and for the wealthy – is, in fact, a question of trade union power, which is to say of class power. As and when art workers are able to make meaningful demands, intermediary positions (producers, curators, middle-managers, and so on) will have to more clearly state their interests and positions. The same is true of ‘political artists’.

The undersigned therefore pledge our active support for the striking art school workers as an act of self-defence, and in the hope for an art industry remade by art workers together:

1. Roberto Mozzachiodi, PCS British Library, UCU Goldsmiths

2. Jack Jeans, Branch Secretary PCS Tate United

3. Gareth Spencer, Branch Secretary, PCS Southbank Centre & Group Organiser, PCS Culture

4. Gemma Copeland, UVW Designers + Cultural Workers

5. Yaiza Hernández Velázquez, UCU Goldsmiths

6. Matthew Hurry, Game Workers Unite UK IWGB

7. Candy Udwin, PCS National Gallery & NEC member

8. Clara Paillard, President, PCS Culture Group

9. Marcela Iriarte, Bectu Art Technician’s Branch

10. Anonymous, Bectu Art Technician’s Branch

11. Russell Carr, Branch Organiser, PCS Tate United

12. Susete Almeida, Women’s Rep, PCS Tate United

13. Alex Fox, PCS Tate United

15. Anonymous, BECTU Whitechapel Gallery

16. Zita Holbourne, Joint National Chair, Artists Union England

17. Gareth Lindsay, UVW Designers + Cultural Workers

18. Paul Valentine, Chair, PCS Southbank Centre Branch

19. Ben Messih, Chair, BECTU South London Gallery Branch

20. Kyle Zeto, Unite Royal College of Art

21. Nick Marro, Branch Organiser, PCS V&A Museum

22. Alisha Ward, Disabilities Equalities Rep, PCS V&A Museum

23. Aimee Upton, Workplace Rep, PCS V&A Museum

24. Matt Phull, Branch Secretary GMB South London Universities (UAL)

25. Becky Turner, UVW Section of Architectural Workers

26. Alice Vodoz, UVW Designers + Cultural Workers

27. Yann Allsopp, Bectu Royal Opera House

28. Eleanor Hall, Women’s Equalities Rep, PCS V&A Museum

29. Emma Dunmore, Committee Member, PCS British Museum

30. Shiri Shalmy, UVW Designers + Cultural Workers

31. Will Attenborough, Equity UK

32. Anonymous, Bectu Art Technician’s Branch

33. Samanta Bellotta, Learning Rep, PCS Tate United

34. Benedict Seymour, UCU Goldsmiths

35. Andrew Osborne – artist's assistant, former RCA technician & UNITE representative

36. Avril Corroon, UCU Goldsmiths and Bectu South London Gallery

37. Janna Graham, Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths

38. Josephine Berry, RCA & MCCS, Goldsmiths, UCU Goldsmiths

[If you would like to add your name / group/ institution to this statement please contact ben AT metamute DOT org]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com