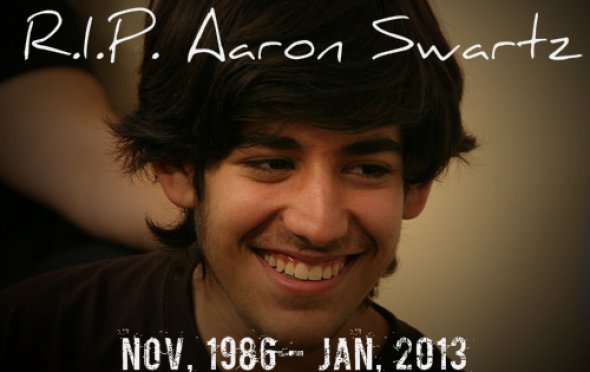

Wired article on the news of Aaron Swartz's death Reposted from: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2013-01/12/aaron-swartz Farewell to Aaron Swartz by Peter Eckersley reposted from https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2013/01/farewell-aaron-swartz Aaron Swartz, hero of the open world, dies reposted from: http://blog.archive.org/2013/01/12/aaron-swartz-hero-of-the-open-world-rip/

Aaron Swartz was easy to pick out of a crowd. I met him only once, at a 2010 gathering of legal academics organized by Larry Lessig at Harvard. In a room full of suits Aaron wore a Google App Engine T-Shirt.

Unfortunately, Aaron's penchant for defying social convention may have been his undoing. He was arrested in 2011 for scraping articles from the academic archive JSTOR. Facing hacking charges that could put him in prison for decades, Aaron took his own life on Friday.

Aaron accomplished more in his 26 years than most of us will accomplish in our lifetimes. At the age of 14, Aaron helped develop the RSS standard. He was an early member of the team that created Reddit, which was sold to Condé Nast (Wired.co.uk's parent company) before Aaron turned 20. Now independently wealthy, Aaron threw himself into political activism.

Aaron had long been acquainted with legal scholar and Creative Commons founder Larry Lessig. When Lessig shifted his focus from copyright reform to institutional corruption, Aaron became an enthusiastic supporter of Lessig's new cause. He joined the Safra Centre for Ethics, which Lessig directed, as a fellow.

In late 2010, Aaron became incensed about a copyright proposal that would eventually become the Stop Online Piracy Act. He founded a group called Demand Progress, which became a key rallying point in the fight against SOPA. He and the team he assembled spent 2011 raising awareness about the problems with the legislation, building momentum for the 18 January, 2012 protest that decisively killed it.

Guerilla open access

Aaron was passionate about public access to information and offended by public information being locked behind paywalls. One paywall that particularly irked Aaron was on PACER, the website the United States judiciary uses to distribute public court records. The courts charged seven US cents (eventually raised to ten) per page to access legal briefs, judicial opinions, scheduling orders, and other documents essential to understanding the judicial process.

So when the courts started a pilot program to allow free access to PACER from 17 libraries around the country, Aaron sprung into action. He visited one of the libraries and reverse-engineered the authentication process the library's computers used to bypass the paywall. Then he spun up some cloud servers and, using credentials purloined from one of the libraries, began scraping documents from PACER. He got more than two million documents before the courts noticed what was happening and shut the pilot program down. When I was in grad school at Princeton, some colleagues and I used the documents Aaron obtained as the foundation of RECAP, a Firefox extension to liberate court documents and store them in a public archive.

Aaron was also outraged about the high prices charged for access to scholarly publications. In a 2008 manifesto, he denounced the legacy system of academic publishing in which scholarly knowledge is locked up behind paywalls. "We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access," he wrote.

In the fall of 2010, Swartz engaged in a bit of Guerilla Open Access himself, logging onto MIT's network to scrape millions of academic papers from the JSTOR database. When MIT administrators booted his laptop off the Wi-Fi network, he entered an MIT network closet and plugged his laptop directly into the campus network.

The stunt got the attention of federal prosecutors, who arrested him and charged him with multiple counts of computer hacking, wire fraud, and other crimes. The feds ratcheted up the charges further in September. If convicted on all charges he could have spent more than 50 years in prison.

We don't know the details of Aaron's death or why he might have taken his own life. In a comment on hacker news, Aaron's mother wrote, "thank you all for your kind words and thoughts. Aaron has been depressed about his case/upcoming trial, but we had no idea what he was going through was this painful."

It's hard to imagine his looming prosecution wasn't a factor. In an anguished Saturday blog post, Lessig describes Aaron's predicament. He was facing a million-dollar trial in April, "his wealth bled dry, yet unable to appeal openly to us for the financial help he needed to fund his defense, at least without risking the ire of a district court judge."

Whether or not it contributed to his suicide, the federal government's prosecution of Swartz was a grotesque miscarriage of justice. Aaron shouldn't have plugged his laptop into MIT's network without permission, but that's not the sort of crime that deserves a multi-year, to say nothing of multi-decade, prison sentence. We should pay tribute to Aaron's memory by reforming the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act to prevent such disproportionate prosecutions from happening in the future.