Untitled

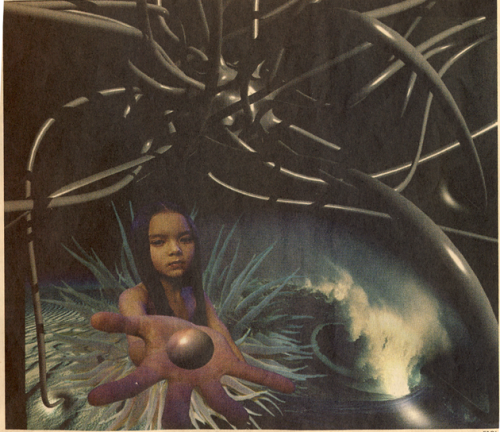

In the musical underground there has always been an emphasis on the bold and the new. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the area of club visuals, which in the space of a few years have moved from day-glo backdrop to feature presentation, bursting out of the club arena, into advertising, into CD-I, and into our living rooms. Film, video, photography, digital technology; all contribute to the overall effect; all combine to create the perfect club, and out-of club environment. As Matt Black of club and CD-I visualises Hex puts it: "The music has been pumped up to a heavy, intense level of stimulation. We're basically trying to ramp up the visuals to be on a par with that."

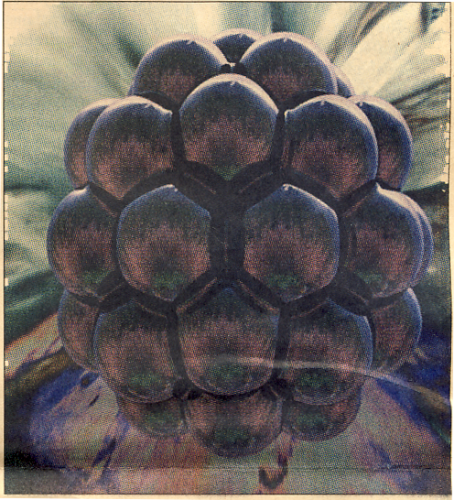

Although characterised by differences, there is a unifying factor among the various creative energies engaged in this field: all have a love of experimentation and a joy in the freedom of what they do. the dynamism of the underground has as usual swallowed and regurgitated available technologies in its own bastardising fashion. The visual side of this multi-media, pot-pourri, like its musical equivalent, is part of a do-it-yourself culture; a 'use what you can, any way you want to' kind of culture. Enterprising film/visual duo Vegetable Vision, who have been projecting club visuals for the last four years and have recently moved into video promotion and record cover design, adhere to this mentality: "We're interested in taking risks, experimentation. We use film loops and slides, animation, photographic images. We scratch film, we feed it into the computer, we distort it. What you get from us is kind of a regimentalised madness, a subconscious cerebral massage."

Matt Black shares this 'mix 'n match' ideal: "Hex embrace a wide variety of styles, simply because we can't afford graphics work stations. We use Omega's, PC's and Macs - we're a kind of punky, pluralist family - and the results that you get are not clean, but they're interesting. All my pictures have come out of just fucking around with techniques and trying to learn them. I like making fucked up things, and I experiment with different types of software to try and make those fucked up things."

For many of those involved, of course, there are strong financial considerations. Buggy G, who enjoys a hugely successful relationship with Future Sound of London as their 'visual designer', is more careful in his approach: "I'm into the acquisition of images, yes, and I'm into experimentation, but I'm very considered in my approach. After all, I'm a commercial artist; I service the music industry."

Given the historical context of this phenomena - the careless Nineties of the Criminal Justice Bill - it would not be surprising if there was some kind of a subtext to this imagery, an outlet for angry voices. This doesn't generally seem to be the case, however. In the up-tempo, `baggage free' world of clubland, indeed in dance -music in-general,-there is often an unwillingness to engage in what people see as negative dialogue, based on the somewhat unsurprising premise that people go to clubs to have fun. The visual artists are part of this wider community and, naturally, their work reflects this ethos. For Noah Clerk and Adam Smith of Vegetable Vision, for example, there is no underlying agenda: "There's camaraderie, sure, and elements of political ideas, but what we do is expressionism. It's not contrived, or part of a larger narrative."

Although there may not be an overtly political angle to the imagery itself, this; doesn't, for Matt Black and Hex, detract from the major issues involved: "We think that this is a good time for the individual to get up and kick the state in the balls. It's the individual versus the state now. Digital technology offers the ultimate nightmare of digital fascism of the expansion and evolution of the human condition. Hex have been evangelists for the idea of do-it-yourself digital creativity by doing it ourselves, and showing you that we can do it; and if we can do it, you can do it too."

The combination of the visual and the audio is integral to this experience, a fact which is arguably both enabling and constraining: enabling in the sense that it provides an audience, an atmosphere and a structure; and constraining, because without it the images can appear somewhat flat. However, as this is a fundamentally multi-media experience, it really ought to be seen in this context; music is one of the essential ingredients to this particular form, part of its past, its present and its future. Each medium supports the other."

"Images and sounds are really all just waves of energy which come into your neurophons and stimulate your brain. The experience works best when they are synchronised to each other" argues Matt Black "and that's not really going on to a significant extent. I think that this year or next year people are going to start talking about this a lot; having the music controlling the graphics and the graphics controlling the music, and maybe human performers interacting and modulating and controlling them both. Those are the areas of interest."

Buggy G. is equally enthusiastic on this subject: "Yes, the combination is vital. I think that the contrast between music and visuals, the cross fertilisation of an eclectic, alien sound with an image, can spark or ignite something. The audiovisual combination provides a point of access, a synthesis of a moment in time that you actually take an impression from. In essence, this is a non-linear narrative, a cumulative signification of language; the accumulation of weird symbolism can send you off."

There is no room or even desire for a narrative if the work is seen in this context. The experience is what is of paramount importance; the sensory experience. Abstract sounds married to abstract images can have a profoundly strong effect when experienced as a whole; the narrative here is of an internal, very subjective nature."

The fusion of more than one element, therefore, is of paramount importance, and it is a failure to grasp this fact which alienates the artists involved in this fusion from those who they see as belonging to `The Establishment'. This, and the fact that, in their eyes, most of the establishment don't seem to understand technology. This sense of alienation extend; to the art establishment. Vegetable Vision complain that they have "been doing installations every week for the last 3 or 4 years" but have faced "closed doors' from organisations that they have approached. According to Adam Smith when he attempted to find funding foi an audio/visual installation he planned to do with Andy Weatherall and the Dusi Brothers, he found nobody willing to give him help or even advice in the Art: Council, the ICA, or any other number of bodies. Disillusioned, he abandoned the project.

Matt Black also feels a gap between what he is doing and what the establishment categorises as "acceptable art", going so far as to state that "art exists only as a commodity to differentiate the rich from the poor. I'm more interested in creativity." Mike Godffrey of Children of Technology, a Bristol collective involved in designing large-scale sight and sound extravaganzas, is similarly dismissive: "The art establishment is entrenched. Digital technology can't be touched or quantified; it's seen and then it's gone. It's also a very, very young art form, a young skill, and costly. This, and the fact that they generally don't understand the technology, is the problem."

Buggy G, who presently has an exhibition in New York's.........gallery, also finds little to smile about closer to home: "I don't have any relationship with the art establishment in this country - I haven't achieved enough credibility in their eyes - but I believe that I'm involved in an evolutionary process which will continue to have a knock on effect on the establishment. It will take time to fully permeate, but I think in five or ten years people will respect a lot of the work that's going on right now in this field."

For the moment, however, the general atmosphere is one of distrust; which is perhaps at least partly due to ignorance on both sides of the street. Clubland, along with the associated art forms which emanate from it, seems unable to cast off its fashionable shackles, its protective edge, which is both its weak point and its strong point. It isolates itself at the same time as being both economically and (art)culturally isolated, but it does benefit from this isolation, as Mike Godffrey discovered to his initial disadvantage: "Coming from an architectural background, I found a lot of inverted snobbery in the club scene, a lot of animosity which had to be overcome. But once I was accepted, once I stepped into the underground, I also found an incredible amount of space in which to develop ideas. There was a lot of co-operation and a willingness to share ideas which just doesn't exist in the commercial sector."

While it cannot be denied that a lot of work that has come out of the club environment is of poor quality, some of-0 it is emphatically not, probably due to the fact that, although artists face financial restrictions, they also have a good deal of artistic opportunity and freedom of expression - rules are broken in the creative space to breathe -whereas when money comes into play, parameters can quickly spring up.....

This is an art form which must be experienced first-hand to be truly appreciated. The images, which can often look very static in isolation, tend to be projected in a dynamic pattern with, of course, accompanying music; it would be unfair to judge the work in isolation. Indeed, it may be unwise. Perhaps this audio-visual extravaganza is part of a late Twentieth Century 'Folk Art' movement, on its own canvas, with its own dynamics, independent of any so-called `Establishment'. Perhaps one day it will not only be appropriated, but 'discovered', intellectualised and sought after in its original form; perfect for that after-dinner, multi-media extravaganza.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com