Spun Spooks

In the BBC’s latest spy-series-cum-M15-promo 'Spooks', the spies have come in from the cold and are lounging about on designer sofas. Mark Fisher investigates their passage from ghosts to yuppies

Who can doubt, in the age of the War on Terror, that Fiction bleeds into the Real? Lying, dissimulation, spin, intelligence, espionage, fiction: Dr Kelly’s death has illustrated the extent to which these already slippery terms are falling into synonymy. The Kelly affair – in which the largest possible geo-political stakes are played out through the messy seediness of betrayal, professional rivalry and the quirks of individual psychology – looks like it could have been scripted by John Le Carré.

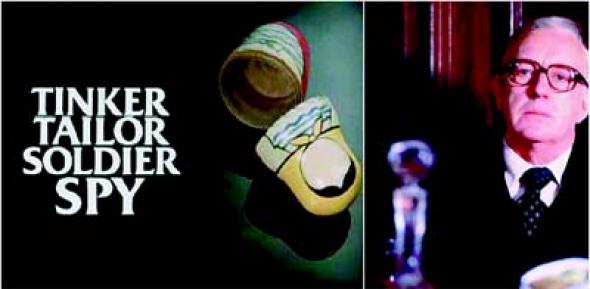

This is at a time when MI5 thought it had laid Le Carré’s ghost to rest. The BBC’s adaptation of Le Carré’s 'Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy' has haunted the agency since it was first broadcast in 1979. As witheringly nihilistic as anything in punk, 'Tinker Tailor' mordantly stripped away the James Bond image of the glamorous spy. Unlike Fleming’s action-man hedonist, Le Carré’s spies were not heroes but jaded civil servants, caught up in a world of generalised mistrust, endemic corruption, and uneasy compromise: a cold, drab East Germany of the soul. Le Carré’s influence was such that the neologisms he coined – ‘moles’, ‘lamplighters’, ‘babysitters’ – actually became used by intelligence professionals. And Le Carré’s image of MI5 has been confirmed by a series of scandals, from Spycatcher in the eighties to the Shayler affair more recently.

Enter 'Spooks', the BBC’s post-9/11 MI5 drama. 'Spooks' is the antidote to Le Carré: a spy series which flaunts its contemporary gloss and youthful vigour. In 'Spooks', Le Carré’s ‘Circus’ has had a ’00s-style makeover: no more plain buff files and dingy offices, just slick, open plan designer spaces, discreetly showcasing up-to-the-minute technology. And gone, too, are Le Carré’s disillusioned middle-aged men. At the frontline of the Spooks service are Tom Quinn (Matthew MacFadyen), Zoe Reynolds (Keeley Hawes) and Danny Hunter (David Oyelowo) – young, energetic, irritatingly well-spoken and implausibly good-looking. MI5 was reputedly perturbed by 'Spooks’' ludicrous promotional strapline – ‘MI5 not 9-5’ – but it has been delighted by the effect the series has had upon the perception of the agency. 'Spooks' has functioned as an unofficial recruiting film for MI5. Last year, the Observer reported that applications to join the service and hits on its official website have doubled since the series began in early 2002.

In 'Spooks', the spy is a hero again. Appropriately for the era of Blair and the Bush-led War on Terror, 'Spooks' has turned up the moral contrast button. This is Casualty or Bill realism: there are Good people and Bad people and a few heavily flagged Ambivalents. For Le Carré, spies were children of Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor: utilitarian cynics whose commitment to expediency made belief impossible. Le Carré was clear. Spies could not afford moral scruples: they were instruments, pawns in a game played by higher powers, the dirty means to ostensibly noble ends. They were in every way grey: ethically compromised, beset by a wintry pessimism, invisible to the society they notionally protected. No cynicism in 'Spooks'. To a girlfriend annoyed by his evasions and absences Quinn can say, without even a hint of irony, ‘I’m serving my country – what’s wrong with that?’ None of Le Carré’s characters, not even the redoubtable, doggedly loyal George Smiley, could have been quite so credulous. If everyone in 'Tinker, Tailor' could appear to be guilty, it was because, in Le Carré’s Augustinian universe, they all were: to be a spy precisely was to be a traitor of one kind or another. The 'Spooks'' characters' moral failings, meanwhile, are minor: computer whiz Danny’s rejigging of his credit rating is a typical slip, easily forgiven and quickly forgotten. Not a trace of Le Carré’s taint. Many of the 'Spooks' sub-plots turn on the spies’ ‘difficult relationship’ with ‘ordinary society’. Much of the first series saw Quinn procrastinating over how far he could commit to a relationship. Yet these practical difficulties have no existential pay-off. To all appearances, MacFadyen, Hawes and Hunter are more or less indistinguishable from any other high- flying graduate on a career path. They don’t look or sound like outsiders; in their ‘focused professionalism’, they could just as easily be lawyers. It was Le Carré’s characters, including Smiley, who were ‘spooks’, hungry ghosts, excluded from the lands of the living.

'Spooks' even felt confident enough to insert a cheeky reference to Le Carré in its opening episode when Quinn uses ‘George Smiley’ as a code word. What a moment of dizzying ontological implosion and hauteur, in which 'Spooks' attempted to capture and contain Le Carré’s Real in its fantasticated promo-imaginary. Such a fantasy takeover might have seemed possible in the twilight years of Blairite spin. But as what remains of the new establishment’s gloss is sheared off by the Hutton enquiry, it is Le Carré who has the last laugh.

BBC official site for Spooks[http://www.bbc.co.uk/drama/spooks/index.shtml ]

Mark Fisher <mark.fisher27 AT ntlworld.com > is a writer on popular and cybernetic culture. He is a member of the CCRU and maintains a blog at [http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org ]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com