Scrying Stranger Aeons

Suzanne Treister's art project and book Hexen 2039 investigates and links a number of occult phenomena to the military industrial entertainment complex. Cameron Bain examines the project and finds that there are empirical reasons for the continuing popularity of mysticism. Treister's approach, he writes, points not only to the surreal foundations of contemporary consciousness but also to a materialist study of power

Today, however, we know that the destruction of experience no longer necessitates a catastrophe, and that the humdrum daily life in any city will suffice. For modern man’s average day contains virtually nothing that can be translated into experience. Neither reading the newspaper, with its abundance of news that is irretrievably remote from his life, nor sitting for minutes on end at the wheel of his car in a traffic jam. Neither the journey through the nether world of the subway, nor the demonstration that suddenly blocks the street. Neither the cloud of tear gas slowly dispersing between the buildings of the city centre, nor the rapid blasts of gunfire from who knows where; nor queuing up at a business counter, nor visiting the Land of Cockayne at the supermarket, nor those eternal moments of dumb promiscuity among strangers in lifts and buses. Modern man makes his way home in the evening wearied by a jumble of events, but however entertaining or tedious, unusual or commonplace, harrowing or pleasurable they are, none of them will have become experience.

– Giorgio Agamben, Infancy and History: Essays on the Destruction of Experience, translated by Liz Heron, Verso, 1993. pp. 13-14.

If, as Giorgio Agamben suggests in the above quote, modern urban life has inured us to ‘experience’ or, even worse, through the degradation of the status of the imagination, vitiated our very capacity for such experience, then perhaps the oft-remarked upon contemporary proliferation of conspiracy theories and interest in such esoterica as psychic phenomena, hauntings, UFOs and the occult is not really to be wondered at.[1] For, if we have indeed forgotten how to engage with the quotidian imaginatively to produce experience, it seems evident that the imaginative faculty in us is of such persistence that, needs must, it will seek other outlets. Thus the (not exclusively contemporary, of course) imaginative turn from that which is clearly apparent to the occult, i.e. that which is ‘hidden’.

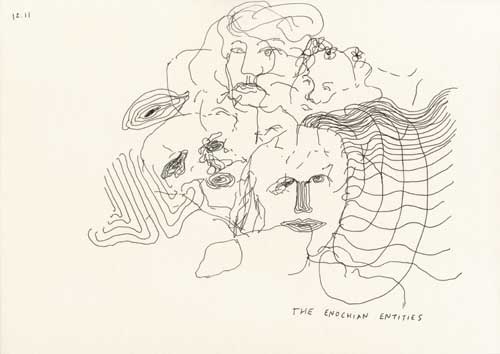

Image: Suzanne Treister, The Enochian Entities, 2006

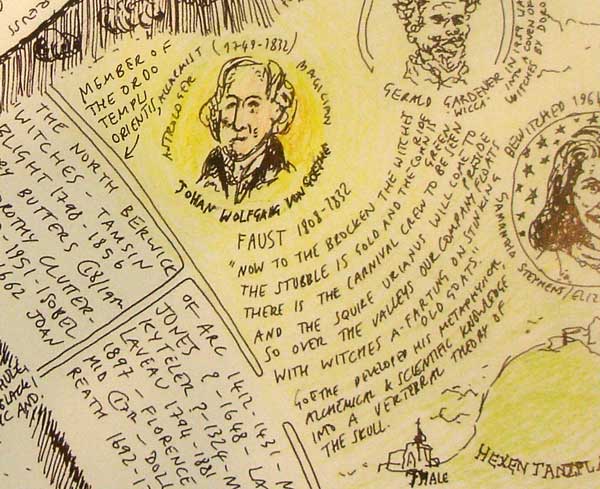

Suzanne Treister’s ongoing research project, Hexen 2039 (conducted by the artist’s fictional alter ego, Rosalind Brodsky), surely represents one of the most wide-ranging and idiosyncratic investigations into the aforementioned esoteric phenomena. Examined for their occult significance are such diverse vehicles and vectors of the arcane as: the music of Modest Mussorgsky, TV towers around the globe, Disney’s Fantasia and certain sound technology developed in conjunction with the film, MGM studios, Chernobyl, British Intelligence agencies, (usual suspect) Crowley, Soviet brainwashing and so on. She attempts scrying with John Dee’s crystal ball and conducts Gematria experiments on the names of historical witches, artefacts for sale in a Dortmund witchcraft shop and the UK locations of MI5 and MI6/SIS offices from 1924 to the present day.[2] What are we to make of such a diffuse and bewildering concatenation of the uncanny?

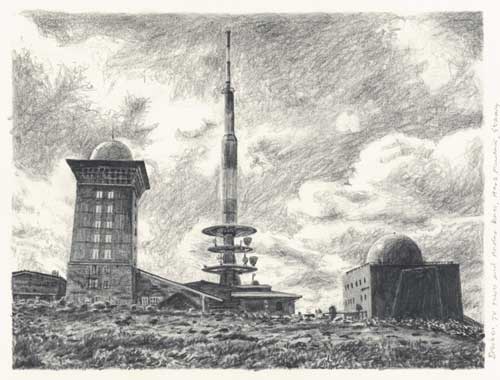

Image: Radar Dome and TV Tower, Brocken, Germany

Well, firstly it is remarkable that the materials presented attain to a semblance of coherence at all. Whether the proposed belief system is ultimately accepted or not is not as interesting as the fact that one’s initial impulse is to accord it a provisional plausibility, i.e. there is an extent to which we would allow, or even wish all this to be true. (‘Suspension of disbelief’, I guess). Richard Grayson’s essay on, and included in the catalogue for Hexen 2039, carries this pertinent quote from Lewis Wolpert on the human brain’s need to discern patterns:

Image: Suzanne Treister, Brocken TV Tower and Radar Domes, Harz Mountains, Germany

It was the mental concept of cause and effect which was critical. Once you had that concept which enabled you to manufacture complex tools, you then wanted to understand other things as well – why we got ill, what happened when we died, why the sun shone or disappeared. Those, too, must have causes. And that’s the origin of belief…..Our belief engine, programmed in our brains by our genes, operates on different principles. It prefers quick decisions, it is bad with numbers and sees patterns where there is only randomness. It is too often influenced by authority and it has a liking for mysticism.[3]

It would seem that most of us do feel the (unconscious?) need to believe in some kind of underlying, ordering structure to life, but why even momentarily entertain the notion of a series of linkages as outlandish as that proposed in Hexen 2039?[4] Surely it goes beyond mere entertainment value?

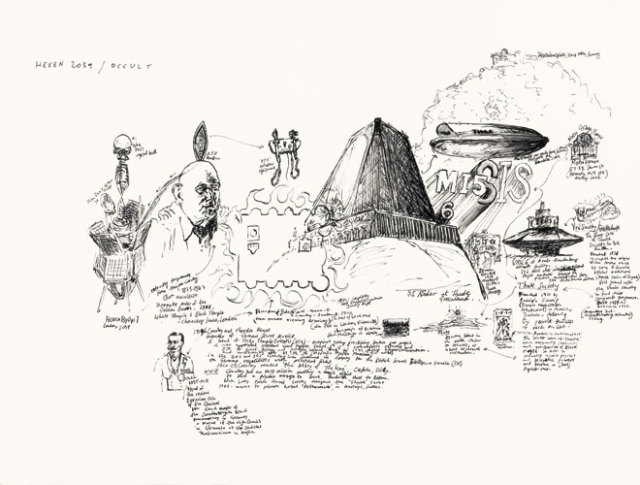

Image: Suzanne Treister, Occult Diagram

The appeal of the occult lies not in the fact that it ostensibly grants entry to hidden truths, but precisely in that it doesn’t. It offers tantalising glimpses, weird, indistinct hints as to what might lie in restive slumber ‘beneath the surface’ or lurk in the shadows beyond the campfire; it intensifies the mystery. That what is hidden must remain hidden is at the core of all occult systems and they always contain internally consistent means of refuting the claim that their hidden ‘truth’ is hidden because it is, in fact, nonexistent. If you fail to turn base metal into gold, you simply haven’t perfected the recipe or your ‘heart’ isn’t ‘pure’ enough and conspiracy theories generally counter incredulity with the refrain that we can only know 'what they want us to know'. It is this vague suggestion of malevolent threat that so often attaches to the occult that lends it its frisson, its unique claim on our imagination. We seem to cultivate the need for the existence of a vast, subterranean complex of proscribed knowledge, to delve into which is an act of dreadful, damning hubris. (Viz. the continuing resonance of the Faust legend and the frequent popular castigation of scientists deemed to be ‘playing God’.) The occult simultaneously tempts us with mystery and reassures us that the ineffable is secure. If there is a nothingness at the heart of the system, we need not worry, as we can never definitively establish whether this is the case. Anyway, to attempt this would be to miss the point. This is perhaps the occult’s one genuinely irrefutable truth: we need these chimeras that remain indomitably, resolutely unknown, for it is in them that the continued possibility of experience lies.

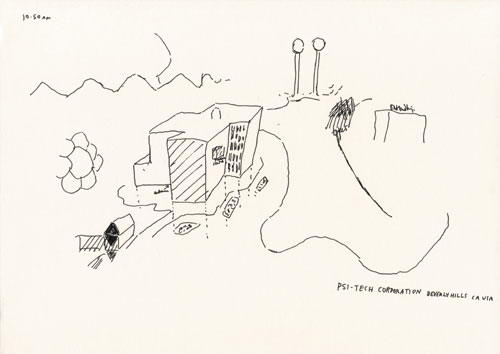

Image: Suzanne Treister, PSI Tech Corporation, Beverley Hills, CA VIA

However, as Treister’s work suggests, although we may casually draw rich imaginative sustenance from the occult while considering its forces to be insubstantial in actuality, the fact is that occult investigations have had and will continue to have ramifications for the ‘real world’.[5] Hexen 2039 is not just an investigation into the demonic allure of forbidden omniscience, but also a critique of this fascination, as is neatly summed up in Grayson’s companion essay again:

'In Hexen 2039, Treister brilliantly uses her scenario of research into real and imagined uses of the ‘supernatural’ and the occult by the military, as a way to explore movements and dialogues between scientific and Enlightenment projects and those based on pre-scientific models of the world. Hexen 2039 suggests the dark possibilities and promises of a resurgent ‘non-rationalism’ allied to technological innovation, either in its development or in reaction to the changes that technology brings.'[6]

Image: Suzanne Treister, Hexen 2039 Diagram

So, while we are presented with an engagingly sprawling hallucinatory fantasy (its scope really is quite mind-boggling), the work as a whole has an ominous dystopian dread to it. It is not, either, the Lovecraftian dread of the arcane, the vague malevolent threat referred to above that the occult exudes, but the genuinely creepy realisation that there are in fact people in positions of power and influence who are eager to know whether occult forces exist (and who devote real resources to ascertaining this) and would harness and exploit them in the name of maintaining power and dominance if they could. It is the very existence of this impulse, this rapacious drive that exists in some for new tools of dominance and subjugation that is so deeply disquieting. We are ultimately left contemplating an uneasy trade-off between the occult as a fathomless reservoir of imaginative experience, able to reinscribe the dull quotidian as weird (in the original sense of the word), and as a source of the truly, all-too-humanly sinister.

INFO

Suzanne Treister, Hexen 2039, Black Dog Publishing, 2006

FOOTNOTES

[1] In keeping, I think, with Agamben, I understand ‘imagination’ here to suggest not so much invention as extrapolation.

[2] Gematria is a Kabbalistic technique which aims to bring to light hidden correspondences between words by establishing numerical linkages between them. Each Hebrew letter has a numerical value, thus words sharing the same numerical value can be seen to be connected and even, in a sense, a commentary on each other. This is just one simple example of how the process may be applied. Treister has transliterated the English and German words she performs her operations on into Hebrew, but whether Kabbalistic Gematria applied to a language other than Hebrew can be said to be valid, I do not know.

[3] Quoted in Richard Grayson’s essay, 'Waiting for the Gift of Sound and Vision' in Suzanne Treister, Hexen 2039, Black Dog Publishing, 2006, p. 145.

[4] A nice encapsulation of the kind of consciousness alluded to here can be found in Leibniz’s elegant formulation regarding music: 'Music is the hidden arithmetical exercise of a soul unconscious that it is calculating'; quoted in The Music of the Spheres: Music, Science and the Natural Order of the Universe, Jamie James, Abacus, 1995, p. 180.

[5] See, for example, Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and their Influence on Nazi Ideology, I.B. Tauris, 1992.

[6] Hexen 2039, p.149

Cameron Bain <c.bain AT ssees.ac.uk> ist Falschentsorger und hat kein brauchbares Heimatbewusstsein

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com