Remnants of Democracy

In their recent blockbuster show and doorstopper book Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel describe a horizontalised network of relations between people and things in which nothing can nor should be excluded from (political) representation. But, argues Anthony Iles, in seeking to universally include the excluded, they fail to allow for the negation of representational politics that such outsiders provoke.

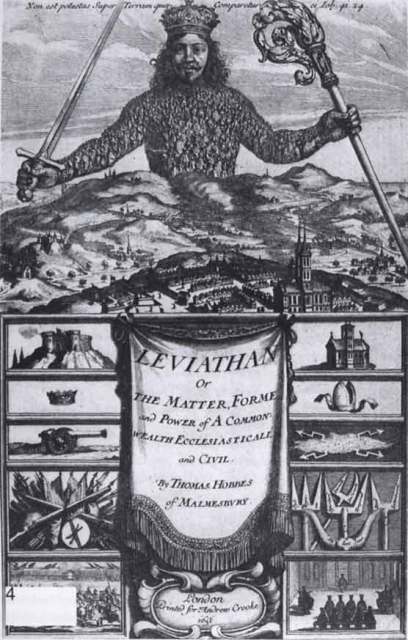

Making Things Public book cover

Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy is the second major exhibition organised by sociologist Bruno Latour at Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, (ZKM), Karlsruhe, in collaboration with its director Peter Weibel. Like the hugely ambitious exhibition Iconoclash, 2003, it is a thematic tour de force of the not-so-new interdisciplinary museology that has characterised the aftermath of postmodernism. Both exhibitions described contentious territory in the arts and sciences and aimed at making methodological interventions therein. Like many exhibitions organised by academics in recent years, Making Things Public is a heady mix of new theory, art works and exhibition design accompanied by a series of events and a programmatic catalogue with contributors from an array of disciplines. Whilst attempts to realise theoretical programmes in the space of the museum undoubtedly feed interdisciplinary collaboration, it is clear from his introduction to the exhibition catalogue that Latour is unapologetically making his programme public primarily in the form of a book. With over one hundred essays and excerpts including new essays by Isabel Stengers, Peter Galison, Chantal Mouffe, Dario Gamboni and over one thousand illustrated pages this is a book generative of enough research points to keep one UK university afloat for several semesters. One gets the impression that what attracted Latour to curating was the possibility of making a cross disciplinary encyclopaedic doorstopper not possible in the context of academic publishing.

The key term for both of the exhibitions Bruno Latour has organised at ZKM is representation. In Iconoclash, Latour tried to demonstrate that each attempt to destroy an image or symbol of mediation, each act of iconoclasm, produced a form of discourse, a material or immaterial layer to its target. After dubiously 'excluding politics' in 'Iconoclash', Latour and his cabal of writers and academics have shifted their focus to directly engage with questions of political representation in Making Things Public. The book and exhibition consider three forms of representation: scientific, political and artistic. Scientific representation presents the object of concern by ‘describing’ it to those gathered around it. Political representation is formed by the mediators who stand in well or badly for the interested parties. Artistic representation is concerned (in the context of this show) with how to represent the sites where people meet and discuss matters of concern. Autonomists beware, by listing many forms of representation and so few ways out of them this book's landscaping of the political amounts to more of an agenda for democratic renewal than a mapping of the politics to come.

So, the book asks, what are 'things' and what is the public? Well, Latour is a sociologist of science and one of the key thinkers involved in the development of Actor Network Theory (ANT), and it happens that it has a few things to say on these matters. ANT attempts the study of social organisation and power adopting the analytical stance that there is no fundamental difference between people and objects. For ANT researchers, social groupings contain not only human-actors but also object-actors, buildings, texts, technologies, ideas, all of which contribute to the interrelation, achievement and survival of the grouping. Social order is an 'effect generated by heterogeneous means'[1], therefore power is simply the ability to organise and interrelate the actors of a network successfully. With the key question of power and hegemony perfunctorily solved, lets move on to the things: the objects which are so animated by this proposition.

Several of the authors in the book excavate an etymology of the word 'thing' heavily informed by actor network theory. 'Thing' we are told over and over is the earliest word for parliament: Althing in Thingvellir (Parliament Plains), Iceland is the site of the earliest surviving parliament, in Old High German the terms Ding, Thing and Thin designated general assembly, court of law, proceedings and site of the court among other meanings. In Icelandic ping denotes an assembly, court, gathering and sexual organ, among other things. Examining the slippery notion of the thing via Heidegger, criticised here by Graham Harman for 'not granting the mechanical and electrical objects the philosophical dignity that they deserve', the book proposes to cover a loose assemblage of issues, knowledges and objects as things that have both a life of their own and are constitutive of social networks. This makes it possible for the books authors to propose a part materialist, part populist political philosophy that expands 'the political' beyond its conscripted playpen. Since 'Each object gathers around itself a different assembly of relevant parties', rather than corralling our notion of the political around the assembly, why not reverse this and weave it around the 'objects' that solicit our attention? When, in the introduction, Latour proposes the neologism 'Dingpolitik' it is as the mission statement of the show, the stepping stone to the project of establishing a properly materialist 'object oriented democracy'.

In the landscape of spin that the exhibition is predicated upon, the political, by steadfastly adhering to the fictions of the truth and the dependence of decision-making upon irrefutable 'facts', has steadily eroded not only confidence in politicians, but in politics per se. As Anustup Basu has demonstrated, in an information rich environment the organisation of heterogeneous information into apparent narratives can be self-perpetuating. Examining the same problem as Slavoj Zizek did in Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle – the talk Colin Powell gave to the United Nations on February 5, 2003 and the justifications for the invasion of Iraq– Latour remains miles from realising the real significance or insignificance of the thing in question: the weapons of mass destruction that Iraq supposedly harboured. The weapons of mass destruction were a smokescreen, a central fiction around which others could be arranged to detract attention from more relevant motivations for the invasion of Iraq. The problem of the implicated but missing object of the debate is not resolved by closer attention to the life of the thing in question, so actor network theory fails as an analytical tool here. Latour concentrates on the invocation of facts and assertions and their inversion in the speech given by the former Secretary of State. Other than the accusation that Powell lied, there is little to accuse him of, there is no critique of power, nor how this power is used to manipulate and associate unrelated facts in an informatic landscape.

In the landscape of spin that the exhibition is predicated upon, the political, by steadfastly adhering to the fictions of the truth and the dependence of decision-making upon irrefutable 'facts', has steadily eroded not only confidence in politicians, but in politics per se. As Anustup Basu has demonstrated, in an information rich environment the organisation of heterogeneous information into apparent narratives can be self-perpetuating. Examining the same problem as Slavoj Zizek did in Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle – the talk Colin Powell gave to the United Nations on February 5, 2003 and the justifications for the invasion of Iraq– Latour remains miles from realising the real significance or insignificance of the thing in question: the weapons of mass destruction that Iraq supposedly harboured. The weapons of mass destruction were a smokescreen, a central fiction around which others could be arranged to detract attention from more relevant motivations for the invasion of Iraq. The problem of the implicated but missing object of the debate is not resolved by closer attention to the life of the thing in question, so actor network theory fails as an analytical tool here. Latour concentrates on the invocation of facts and assertions and their inversion in the speech given by the former Secretary of State. Other than the accusation that Powell lied, there is little to accuse him of, there is no critique of power, nor how this power is used to manipulate and associate unrelated facts in an informatic landscape.

Facts and values, Latour asserts, are frequently indistinguishable and the distinctions made between them is often un-useful if not dangerous. So, from studying science as culture, the proponents of Actor Network Theory have moved on to address the ideological supports that have propped up the questionable interests of science as a separate and unified discipline. Nature has long been used as metaphor and model for human assembly and provided the stability and rational foundation upon which man has erected so many questionable politics. However, now 'it seems nature is no longer unified enough to provide a stabilising pattern for the traumatic experience of humans living in society'. The theme of the human construction of the animal and in turn construction of the human in regard to this image is returned to throughout the book. In the article ‘Sheep Do Have Opinions’, Vinciane Despret questions the methodologies and assumptions researchers in the past have applied to sheep, and finds that given the conditions of a reversal of the organisation of their lives around competition for food, the sheep begin to indulge in un-sheepish behaviour and in turn 'make their researchers say more things'. As well as telling us about animals, the sheep, and their researchers, suggest an analogy – that of the assembly in which the behaviour of political subjects is a matter of the conditions and expectations in which they are framed. This analogy corresponds to the figure of the 'idiot' as described by Isabel Stengers in her 'cosmopolitical proposal'. The idiot is derived from the Greek meaning 'private person', the idiot does not participate in the forms of public life available, neither understanding nor being understood in them. The idiot frustrates, being the one who 'neither objects nor proposes anything that “counts”. Stengers uses this figure to unravel the ethical utilitarianism that ties all human life to the market and to its political institutions.

'In this show we simply wanted to pack loads of stuff where naked people were supposed to assemble simply to talk.'

Whereas the exhibition was packed with tools and technologies for encouraging assembly and discussion, the book is inversely filled with images of assemblies, ceremonies, parliaments, allegories, demonstrations, group photos, crowd scenes exhorting one to recognise both a public and a multiply institutionalised general will. Flicking through these one experiences the pleasure of a child with an encyclopaedia staring at scenes and architectures whose political content and inhabitation one must guess after. Seeing what politics looks like through the anthropological lens allows for some of the multidimensional aspects of political discourse to be drawn out and the possibility of some hidden actors to emerge. Nonetheless, despite the establishment of a 'crisis of representation' as one of the key premises of the book, its authors fail, almost serially, to find any concept of politics other than representational politics. Like any encyclopaedia it is a partial one, as much a map of the issues it cannot and will not contain as those it can.

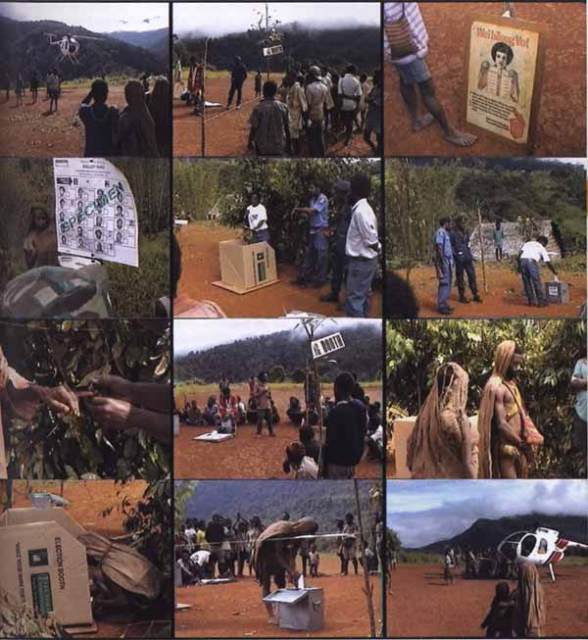

Image >> Pierre Lemonnier, Pascal Bonnemère, Démocratie héliportée chez les Ankave de Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée

Arraying endless examples of failures of democracy to coincide with so many politically challenged actors, without access to the tools, skills or time to become informed about the issues that are decided for them, perversely Latour and many of the authors in the book use this ammunition as an argument not for the jettisoning of democracy, but for the system of representation as one important prosthesis among others. Thus it is somewhat nauseating to read the optimistic account by Pascal Bonnemère and Pierre Lemonnier of an election in Papua New Guinea amongst the Ankave people of the Suowi Valley. Traditionally horticulturists and pig-farmers more inclined to retreat into their huge forests than to receive the missionaries, administrators, police and work-enforcers who sought them there, the Ankave participated in elections for the first time in 1997, voting for representatives, whose names or policies they do not know and who have never visited their territory. In a correlative to the Ankave, Philip Descola gives an account of the Achuar Indians of Ecuador, obliged to vote in presidential elections, whose love of democracy is only exceeded by their indifference to this or any other political process. The Achuar do not vote, have no form of assembly or court, no chiefs or clans, the only time they assemble as a collective at all is to wage war. Unlike the Ankave the Achuar have not been assimilated into a system of representation that doesn't recognise them, for after all what is there here that Western-style democracy could recognise?

Here is the book’s central conflict: early on Latour indicates that the object-averse tradition of political philosophy has ignored objects in favour of bodies and in particular has concentrated on homogeneous bodies of parliaments and assemblies rather than the 'giddy multitude' that representational politics disinterestedly governs and disciplines. The material, human and animal worlds Making Things Public describes is filled with so many political actors who are treated but do not ‘count’. The attempt to include the excluded subject of democracy as excluded is precisely what turns it, in Georgio Agamben's terms, into a 'machine of death'. The unified body of 'the people' is predicated on the divided body of the foreigner and the subaltern. Frustratingly, Latour employs this as an argument for rather than against mediation.'Making Things Public' is proposed as the study and improvement of mediators, material and human. There are no end of examples of the failures and aporias of scientific and democratic thought, but none that could not be solved through better mediation through closer understanding of the things that animate and are animated by networks. It is a myth that the politically challenged should feel that they owe democracy anything when it is precisely the system of democracy that strips them of agency, disempowers and excludes them. Then what exactly they owe democracy is a moot point that Latour nor his colleagues are prepared to discover. The smoothing of the material world into so many things elides the reality of material as property, commodity, use or exchange value. Things are alienation as much as they are facilitation. Latour’s analysis ignores the reality that asymmetry of means and of access is structured by power, by the designated assembly, protected and affirmed by the rule of law and of property. Until this changes there remains room in the theory of the public thing and the expanded assembly for the unequal actor, but in the network there are also 'rights, duties, or responsibilities' and fewer ways out of them than ways in. Just as actor network theory in its reductionist mode, could be criticised for further reifying an existing social order, so this book continues to confirm and reproduce the regime of power, property and work that it takes for granted.

Here is the book’s central conflict: early on Latour indicates that the object-averse tradition of political philosophy has ignored objects in favour of bodies and in particular has concentrated on homogeneous bodies of parliaments and assemblies rather than the 'giddy multitude' that representational politics disinterestedly governs and disciplines. The material, human and animal worlds Making Things Public describes is filled with so many political actors who are treated but do not ‘count’. The attempt to include the excluded subject of democracy as excluded is precisely what turns it, in Georgio Agamben's terms, into a 'machine of death'. The unified body of 'the people' is predicated on the divided body of the foreigner and the subaltern. Frustratingly, Latour employs this as an argument for rather than against mediation.'Making Things Public' is proposed as the study and improvement of mediators, material and human. There are no end of examples of the failures and aporias of scientific and democratic thought, but none that could not be solved through better mediation through closer understanding of the things that animate and are animated by networks. It is a myth that the politically challenged should feel that they owe democracy anything when it is precisely the system of democracy that strips them of agency, disempowers and excludes them. Then what exactly they owe democracy is a moot point that Latour nor his colleagues are prepared to discover. The smoothing of the material world into so many things elides the reality of material as property, commodity, use or exchange value. Things are alienation as much as they are facilitation. Latour’s analysis ignores the reality that asymmetry of means and of access is structured by power, by the designated assembly, protected and affirmed by the rule of law and of property. Until this changes there remains room in the theory of the public thing and the expanded assembly for the unequal actor, but in the network there are also 'rights, duties, or responsibilities' and fewer ways out of them than ways in. Just as actor network theory in its reductionist mode, could be criticised for further reifying an existing social order, so this book continues to confirm and reproduce the regime of power, property and work that it takes for granted.

Image: A northern bottlenose whale stranded in the River Thames in January 2006

In January this year, Londoners received an unusual visitor. Apparently making a homage to the site of the UK's parliament, a seven-ton Northern Bottle Nosed whale made its way up the Thames to Westminster and floundered there for an afternoon. Pundits struggled to understand what the whale’s intentions were, was it trying to get back to the Atlantic across the land mass of Southern England, was it injured, confused by military radar, or sick? One commentator of religious persuasion came close to accurately summarising the heavy burden this beast carried upstream with him :

For a few days, the entire city of London shared in the experience of the suffering remnant, the remnant that has been rejected by human structures, the remnant that has been forced to wander in the solitary wilderness, with no support or encouragement from man and his earthly structures. Instead of acting indifferently, the people of London sympathised with him; they put aside their schedules and their daily activities, and they did all they could to help him out.[2]

The sympathy of Londoners was in great evidence that day, and it was equal to the whale's fright. The whale could not begin to understand the gestures of the humans standing in the river’s edge nor could the humans helpfully interpret those of the whale, the spectacle of human sympathy and animal suffering did not coincide. The whale's encounter with the British people and its democratic institutions was, for the whale, as for Jean Charles de Menezes, fatal.

Footnotes

[1] John Law 'Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity' 'http://web.archive.org/web/20040214135427/http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/soc054jl.html

[2] from http://shamah-elim.info/p_lndnwhl1.htm

EXHIBITION: Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, March 2005, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany, http://makingthingspublic.zkm.de/fa/dings/DingPolitikHome.htm BOOK: Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, eds Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel MIT, September 2005 ISBN 0-262-12279-0

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com