The Regeneration Railway Journey

With New Labour's era of urban regeneration hitting the spongiform buffers of the Big Society, Owen Hatherley's Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain surveys the train wreck it has left in its wake. Review by Neil Smith

Let's jump a train at one of London's iconic 19th century steel and glass locomotive palaces, built in the age of coal and steam, and tour the architectural gems of Britain's regenerated urbanism. Railways rarely offer the most salubrious tourist views of a city, for if competition is the putative glue of society then garbage heaps and otherwise invisible hovels, abandoned wastelands, prisons, toxic dumps and general dereliction all seem to compete with the arse-end of industry for the din and danger of the tracks. But if we get off in the city centres this detritus of capitalist urbanism will surely be left behind. Owen Hatherley jumped that train with a photographer friend, cityspotting for some months, and the result is A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain. For Hatherley, the view from the tracks may not diverge so much from these city-centre vistas.

Some cities, such as Hatherley's home town and starting point, Southampton, apparently 'missed the memo' from the Blairite centre according to which a new planning regime was taking over from the cruel Thatcherite mandate of laissez-faire. The excesses of modernism were to be demolished or rehabilitated in favour of 'regenerated' mixed use and mixed income housing. Yet there is little evidence in the landscape of this would-be Solent City to suggest that had the memo actually been received it would have made any difference. The 'spectacular incoherence' of Southampton, writes Hatherley, offers 'stacks of containers full of goods on one side' and 'stacks of containers full of people buying goods on the other.' Regeneration and market outcomes are two sides of the same coin. By contrast there's Milton Keynes. Planned in the white heat other-worldliness of pre-revolt '60s optimism, this 'social democratic version of Los Angeles' was completed under the Barratt-Wimpey-Bovis regime of urban utopia, but is not yet enough of a failure to have suffered significant regeneration. Nottingham has its share of regeneration banality and matching social control - repressive police signage menacing public space - but also some of the best new architecture to escape the regeneration mulcher, making it the ideal host for an art exhibit on 'Combined and Uneven Geographies.'

Image: Will Alsop’s CHIPS Apartment Building, New Islington, Manchester

Across the land, the uneven geographies are palpable. Much as urban neoliberalism is starker in Britain than in the landscapes of North America, the epicentres of Blairite moral irruption seem to be etched into the cities that most resisted Thatcher. Sheffield (the erstwhile self-declared socialist republic of South Yorkshire) might exhibit the most lamentable and sinister side of the whole history from brutalism through to regeneration. Widely praised as an architectural paragon for its postwar council housing schemes, Sheffield modernism, from Castle Market to Park Hill and Gleadless Valley, broadly worked as a social experiment in urgent times. But then came an onslaught of deliberate neglect, economic disinvestment, utopia-slagging and moral opprobrium, all coaxed on by Thatcherite academics who served up this decaying 'streets-in-the-sky' housing as new frontiers for capital investment. The city found itself rebranded with the pathetically uncreative name, 'Creative Sheffield'.

As much a travesty is Salford (a 'straggling mess' of regeneration dregs), and then there is Manchester, supposedly the designer brand for creative 21st century regeneration. The real lesson that Hatherley implicitly draws from this city, strange as it may sound, is that the utopian architectural brutralism of Hulme was too good for the working class and is now replaced by a far more vicious and all-encompassing social brutalism. As in Sheffield, this regeneration by root canal has excavated thriving, internationally recognised post-punk music and cultural scenes (creativity anyone?) and anything else organic in the inherited concrete. All trace of this moment has been driven from the streets and clubs, estates and record studios and desperately mummified in new museums devoted to the newly old - in the vain hope of pulling in tourist pennies. Manchester may exhibit 'the most complete attempt to redesign an entire city on the basis of an alliance between property development, the culture industry and ubiquitous retail' and the result is not good.

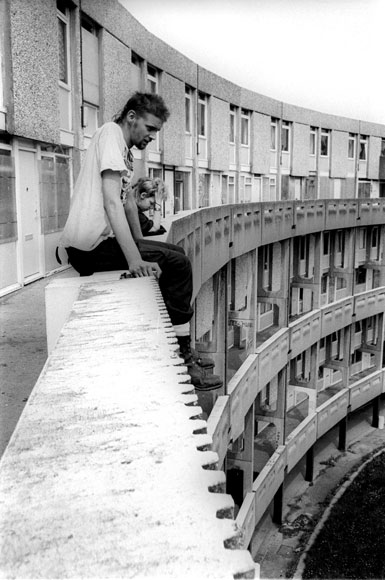

Image: Charles Barry Crescent, Hulme, Manchester. Photograph by Ian Robinson

Despite the predilections of architectural critics, it never was the architecture per se that was the 'urban problem', of course; rather it was the occupants. Hatherley exceeds even good architectural criticism by so fully embedding the national urban landscape within the social relations that conjure it; thus some brutalisms are more brutal than others. How else are we to square the vitriol aimed at the architecture of working class high rises and council estates with the survival, even adoration, of London's brutalist Barbican Centre, the demolition of which would have deprived the genteel classes of their cultural fix. Brutalism for the toffs works just fine, thank you very much.

In Glasgow too 'architecture provided a convenient scapegoat for political ills', but here as in Tyneside with its Byker Redevelopment, despite occasional convulsions of identikit postmodernism and various subsequent plooks on the urban landscape, new rounds of urban death by regeneration were generally better kept under control. For all their vaunted passing, some areas of Glasgow tenements escaped the re-drafting board, albeit usually the more ornate middle class variety, and have been rehabilitated, not always for their old tenants. Hatherley missed a golden opportunity by not alighting en route to reveal the trainspotting reality below the façade of Edinburgh Castle, but the smaller target of Cambridge is amply dispatched.

Returning to London via the worst-of times, best-of-times West Riding and a hapless vernacular-free Cardiff, the railway journey runs out of steam. The narrative sobers up, perhaps because Hatherley ends up in Greenwich, his home of the last few years, where a knowledge of its nooks and crannies defies more freewheeling generalisation. There, surrounded by bygone monuments of British militarism and scientific imperialism, he bravely finds a contrapuntal geography - renegade exceptions to the vague, theoretical social democracy so ably moralised into market-driven benchmarks by New Labour: a climate camp and, across the river, 'the Battle of Cable Street' mural among others from the socialist realist Mural Workshop, 1980s remnants of international and anti-racist solidarity movements. But the tragic exhaustion of early 21st century regeneration policies, their new wastelands and Potemkin villages, is never far from view. They are on full display along the post-Millennium Thames, a strangely empty river whose banks became one great brownfield site now pock-marked by 'relics of New Labour's New London, a mess of the punitive, the crassly money spinning and the literally fraudulent.' The 2012 Olympics will gild the remains of this socio-industrial ghetto with an already guaranteed legacy of mass state-planned gentrification, successful or otherwise.

Image: New Housing by ECD Architects for Places for People, Hulme, Manchester

But wait. The story has one last burst of energy as Hatherley goes to Liverpool where the last days of municipal socialism, before it succumbed to Thatcher, produced some genuine bright patches which still give some working class areas a 'kind of dramatic urban grain.' The city has its share of 'inept urbanism', but it also hosts a range of well meaning alternatives that have minimised the displacement of the working class, keeping more of the population close to the city centre, all be it in tragicomic suburb-envying and depopulation induced bungalow-and-garden schemes. Whatever its promise, Liverpool eventually fails to relieve the melancholy of the whole railway journey around the wreckage of Blairite urban regeneration.

So what do we learn from all this? The Guide to the New Ruins cuts through the vomitory regeneration verbiage like a bulldozer demolishing houses. Hatherley conducts his own root canal on regeneration ideology. Establishing a chronology of architectural moments from postwar modernism and brutalism, through the free market incoherence of Thatcherism and subsequent revolts, to the kinder, gentler neoliberalism of Blair, he makes an inchoate landscape as coherent as may be possible. The physical destructiveness and social miasma of regeneration policy pupates from this tour as its own distinct era, and Hatherley captures a larger historical shift here. Many radical ideas have been eclipsed by the neoliberal tsunami and, especially in Britain, radical urban critiques have themselves been regenerated out of existence, 'curdled into an alibi' for gentrification. Regeneration was always ever a gentrification strategy, and we knew it. We knew it from Blair's 1997 launch of New Labour's regeneration policy from the stigmatised Aylesbury estate in London where the desperate '70s class-neutral language of revitalisation, recycling, renaissance and especially regeneration was revived in the 2000s - a language as deliberately anodyne as it is ideological and mendacious; an environmentally friendly cover for class cleansing in the urban landscape. And if we missed it then, we certainly knew it from the first Urban Regeneration Task Force proposal in 1999. Felled forests, polluted lakes, an overtaxed liver, all of these may experience natural regeneration under the right conditions but this regeneration, by definition, comes from below. The capitalist economy is anything but natural, the craven idolatries of neoliberal stoolies notwithstanding, and its gentrification is top-down policy.

The organised left only ever had a spotty record on housing and community politics and no real opposition to Blair's regenerationism emerged there. More broadly, the political defeats after the mid 1980s left many with little energy to fight, and many otherwise good souls, exhausted by the defensive and broadly failed struggles against Thatcher and desperately keen to see a Blairite alternative, concluded that if they couldn't beat them they better join them. Ex-radicals became frontline regeneration managers for local councils, others even became developers. Architects and planners, not generally given to the language of gentrification, leveled no audible objection; and few academics put up any resistance. In the last decade a British academic applying for a Research Council grant to study gentrification would be well advised to clean up her language and become a convert to 'regeneration', and most did. The melancholy of political defeat in the 1980s became the new normal for subsequent generations of urban professionals, and the same melancholy was built into the wrecked urbanism in the 2000s.

Image: Park Hill, Sheffield in the 1950s

There is considerable irony in this. The language of 'gentrification,' first coined in London in the 1960s, has been a stalwart British export to the rest of the world. Its international ubiquity today - the word has variants in Spanish, Cajun, Polish, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Mandarin, Hungarian, Korean and is a fixture in North American public culture - results from an important political and ideological struggle. Some places were protectionist (retaining 'embourgeoisement', the French have history on their side insofar as that term was already current in the 19th century), while others launched concerted media campaigns. In New York, real estate capitalists took out a series of newspaper adverts asking 'Is Gentrification a Dirty Word?' But in the face of the obvious they lost. Today the class-specific language of 'gentrification' proliferates around the world while in its homeland it has been denounced. In these poststructuralist times we are admonished to change the world by changing the discourse, and the British eclipse of 'gentrification' in favour of 'regeneration' is a case in point: Tony Blair as poststructuralist-in-chief, and developers Urban Splash as his commando battalion. Talk about the destabilisation of categories!

The Cameron-Clegg coalition of naked convenience has little appetite for regeneration policy having cancelled the planned redevelopment of Blair's ill-fated Aylesbury estate. With or without regeneration, the 'Big Society' represents just another phase of neoliberal destruction, with even fewer protections against large scale state-orchestrated displacement. If the Big Society seems vague, vacuous and pathetic, this is not an accident, and its vacuity distinguishes it from Blair's regeneration initiative. Today in the wake of growing opposition, failed global wars and a worldwide financial crisis, neoliberalism is dead but dominant. It is dead insofar as it has no new ideas, bogged down in the brownfield site of its own effluent; it is dominant insofar as neoliberalism still has no system-wide challengers, Europe's anti-austerity revolts and the revolutions of northern Africa and the Middle East notwithstanding. The Big Society hitches itself to stagnant neoliberalism but the engine is never in gear and can't to drive forward a dead project.

Image: £146m regeneration of Park Hill, Sheffield

That might seem like good news, but it isn't really. The beast of urban neoliberalism is made of sterner stuff than to die without a fight. And so the recent public scrum over housing benefits gathered around a rhetorical question, aptly summed up in one BBC News headline: 'Do the poor have a right to live in expensive areas?' We can learn two things from this debate. First, the moral cladding of 'regeneration' has done its work; thanks to state policy, the market with all its powers of cataclysmic abandonment and investment has been unleashed, resulting in the present housing crisis, in Britain and elsewhere. Second, the class-cleansing intent of urban policy, whether regenerative or socially big, is beautifully exposed by a magnanimous transposition of the question: 'Do the rich have the right to invade poor people's areas?' (which may just be how so many poor people find themselves suddenly living in 'expensive areas' in the first place). What does an answer to that suddenly unrhetorical question say about the liberal equality of rights enjoyed by the poor and the working class? The residual Blairite swaddling of the question - 'do the poor have the right ...' - camouflages the naked class politics of austerity.

If Hatherley's language is vibrant, unbowing and his critiques sharp and well aimed, it is political melancholy that nonetheless hangs over the entire journey. A next railway journey therefore beckons. It seeks fresh shoots of political growth amidst the dereliction of the new ruins visible from Hatherley's train. Much like its urban alter ego, political regeneration will surely involve creative destruction, the clearance of ideological wreckage and the nurturing of new brownfield sites in anticipation of greenfield political growth. That's a railway journey I want to be on.

Neil Smith <Nsmith AT gc.cuny.edu> teaches geography and anthropology at the City University of New York, and is author of numerous books including New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. His American Empire: Roosevelt's Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization won the LA Times Book Prize for Biography, 2004

Info

Owen Hatherley, A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, London: Verso, 2010

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com