No Place Like Home

Peter Carty examines two conflicting strategies in contemporary psychogeography and asks whether rules and regulations or radical subjectivity is the way forward

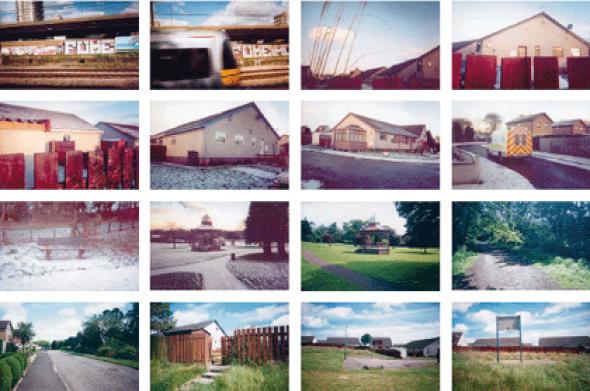

The fashionable pursuit of remapping the cityscape is taking diverse forms – from rigid adherence to rules to wilful transgression. In Holland, Wilfried Hone Je Bek and his fellow psychogeographers (see [www.socialfiction.org]) are developing a ‘generative psychogeography’ with dÈrives derived from pre-determined algorithms. The hazards of social fiction’s adventures for other pavement users aside, fracturing the regime of the city through such strict rule-following may not be a realisation of psychogeography’s potentials. Arch prankster Stewart Home, who has long made psychogeography a basis of his art practice describes a much more flexible approach in his latest pamphlet (How I Discovered America, Infopool No.6, 2002 [www.infopool.org.uk]). Home’s premise is that America (or Amerikkka, as he calls it) exists everywhere as a state of mind. So he’s journeyed around selected spots in Britain to find it for himself, taking photographs to document his exploits.

Some of Home’s pictures show housing built for American servicemen working at an intelligence installation; but most have no connection, however tenuous, with the ‘actual’ USA. The implication is that psychogeography need not insist on a connection between interior and exterior environments, a return to the practice’s first principles that recovers its imaginative and critical potential. Home’s approach, which resembles the old tactic of navigating one territory with the map of another, deploys an apparently radical subjectivism to focuses the reader’s attention on the (philosophical) idealism of America itself, a simulacral Kingdom of Heaven-on-earth.

Some would consider this approach politically suspect, of course. Psychogeography has often been attacked as anti-materialist, bourgeois and idealist. Home seems at once to flaunt the idiosyncracy of his ‘viewpoint’ and deconstruct the notion of there being a ‘psychological’ subject to whom this view could be ascribed. Those wondering if psychogeography’s increasingly gentrified conceptual by-ways are still worth visiting will find, like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, that there’s no place like Home.

Laboratory Italy, by Wu Ming 1 and Luther Blissett, Infopool No.7, 2003 is available now at [http://www.infopoool.org.uk]

Peter Carty <pcarty AT tesco.net> is a writer and journalist

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com