Interview with Nils Norman

Artist Nils Norman has engaged extensively with the language of urban planning, architecture and urban regeneration. Josephine Berry Slater and Anthony Iles interviewed him about the positioning of his work between the mutually exclusive worlds of art and urban development

How do you characterise the sites and terrains of your practice? What do they have in common?

These vary from education to galleries, museum exhibitions, public commissions, publishing, collaborations, symposia, websites etc... what links them all is a discourse in urban issues, the production of public space, its representation and its privatisation. The idea of the neoliberal city and its critique was quite an important centralising topic or flash point... until a few months ago when that ideology seemed to have collapsed... they seem to be trying to resuscitate it as we speak and it will probably return in a more fascistic and draconian form, the design and its implementations will be interesting. A student in Copenhagen told me that for the upcoming climate conference the police have a water canon with dye in the water, so anyone with a drop of it on their clothes can be easily identified and arrested just for being there! In London we will probably end up with more check-points, barriers, X-ray machines, searches, it will be like travelling to and in Israel. But you'll be here at home just trying to have a pint in the West End or going to the bank. One interesting legacy of the neoliberal city and its financial centre was a hysterical ramping up of fortifications for only certain groups of people, interests and zones. Other parts of the city and country were left to rot, these are contradictions and landscapes I visit a lot with art students I teach.

Image: Nils Norman, the 80m Trekroner bridge, island and lake for the new town of Roskilde, Denmark, 2005

For you, what has historically been the relationship between the artist and the city. How do you see this relationship in its transformation over the last 10-20 years?

There is a chapter in T.J. Clarke's book, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (Knopf, 1985), about painting and the representation of Hausmann's Paris that is an important description and way of understanding artists and their political relationship to the city, I think this has continued until maybe the mid noughties when artists became so inscribed within urban regeneration processes that anything they do – any intervention, protest, happening... whatever... just becomes directly woven into the gentrification fabric being spread across a neighbourhood. It's depressing, but as gentrification became such an important privatisation tool so did the way it functioned and the people that helped it to function efficiently, like artists, and I don't think I'm being too cynical here. Manfredo Tafuri's book Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, (MIT Press, 1976) was also influential to me in regards to understanding how artists help commodify certain disciplines and areas helping them open up to new markets.

To what extent is your work an analysis of existing urban landscape? To what extent does it seek to remake existing landscapes?

An analysis of existing urban landscapes is for me important. As research, maybe similar to how Mike Davis looks at the urban context or Neil Smith, Setha Low, Sharon Zukin. I see what I am trying to do and what I have done in the past as a form of critique rather than reform. To be able to actually stand in an urban planners office and tell the planners and council members that what they are doing is crap rather than rhetorically state this in a group show to the curators who organised it, seems more relevant within the context of this sort of art activity.

The model, the plan, the projection, the drawing – your work has variously employed these different forms and genres. What relationship do you see them having to the built environment – how do they act upon it, symbolically, critically, temporally?

I started using the language of the urban planner or architect as I always went to visit city halls, architecture institutions and planning departments to look at their models, plans for future projects. It was one of the only interesting interfaces I knew of where the State was trying to communicate with a small community of people directly, using a form of artistic representation – models and drawings – to put their ideology across, I thought that reproducing and subverting that language might be an interesting thing to do artistically.

I lived in NYC for most of the '90s and many new changes were being made to the city by the then mayor Rudolph Giuliani in terms of his Quality of Life campaign, gentrification, defensive design and the privatisation of parks. Gentrification at that time was still quite a marginal discourse. Now there are hundreds of books on it and is being used as the top global city reclamation strategy, with artists or ‘creatives' on the front line. I don't think that was anticipated really in 1984 when Rosalyn Deutsche made a concrete link between art, artists and gentrification in NYC's East Village.

Regurgitating the language of the architect and planner in a way that was opposite or different to the usual planner ideology was for me interesting and still is. The powerpoint presentation is also a good way of doing this. Stephan Dillemuth and I have also been working on dramatising financial journalism, revealing its contradictions and absurdities.

Image: Nils Norman & Stefan Dillemuth, View from the Top: Bill Ruprecht, Chief Executive of Sotheby, YouTubevideo, 2008

How would you relate the legacy of community art(s) to your work?

I'm not sure what legacy you mean...? My understanding of community art varies from country to country, city to city... I have worked with students from South and Central America where community art projects are part of an important struggle and integral to an idea of revolutionary activity outside of any regeneration discourses – to projects in Europe where a lot of cash is pumped into an art consultation process that maybe has no real agency at all. But it really does vary from zone to zone. It is also different from project to project... I have not really worked that much with 'communities', in a kind of old school idea of the term as a genre. Working in a gallery, museum or institution you are working with a community as such. A social process, it seems maybe more interesting to address or analyse this institutional process, its social aspect, its culture.

What role does participation play in your work?

It doesn't really play such an important role. I usually try and avoid any overtly participatory invitations as I always find them deeply problematic. I am interested in a long term participation – over decades – usually more private collaborations and discussions with other artists and friends.

One of the few projects where I worked closely with 'a community' was with the Serpentine Gallery where I worked with homeless teenagers at The Connection, a day centre for homeless kids in Charing Cross. It was over a period of two years and I was there, for some periods, working twice a week. The Serpentine was very generous to allow such a long working period and it's unusual for a museum to give you that time, but at the end of the day I think it is the institution that gains the most from these initiatives, not really the individuals, and of course the artist benefits, depending on how they personally decide to invest that particular form of cultural capital.

Your work often brings 'alternative' lifestyles and cultures into the context of instrumental urban transformation projects. What is the status of these 'alternatives' and how do you see your practice as mediating or introducing them into professional architectural and urban planning practice?

I have been interested in the idea and history of utopia and have been using it in my work since the early 1990s. I have tried to copy an early satirist like Jonathan Swift's use of utopia and parody as a kind of critical tool or lens through which to analyse existing conditions and the conditions of the site I might be addressing. Alternative lifestyles, models past and present are an important part of this research – permaculture, the Appropriate Technology Movement, adventure playgrounds, ‘Non-Plan' to name a few, are ideas, methodologies and systems that I try and bring into a proposal to highlight potential alternative ways of thinking but also to reveal the limitations of the site, a possible solution and the meagre results small reformist projects can engender. To create a more layered and complicated dialogue about a site, urban planning and the possible alternatives with all the grotesque contradictions a dialogue about these things within a capitalist society brings up.

Image: Nils Norman, Gateshead Hoarding, 2005. 'A landscape portrait of Gateshead, a deprived area of North England that is in the process of being regenerated, using culture as the main strategy of renewal.'

In what ways have commissioning agencies set the conditions for your work?

Most commissioning agencies I have worked with have tried to manipulate and control the outcome of the project if they don't like something. Public institutions increasingly reproduce the less desirable culture and identity of corporations. (Sometimes they are forced to by the State or through competition and sometimes their directors just choose to because they are too stupid to think of another, more interesting model). It makes that culture and environment less interesting to work in. One of the reasons I became an artist was to avoid having to work in a corporate environment. But this move towards a corporate identity brings with it all the baggage of brand identity, marketing strategies, etc. And that's when censorship and project manipulation steps in.

But it's important that it's public money that is being spent, and that has to come with certain guidelines. It is when it's washed together with private funding that you begin to get a very tangled and confused money trail that can be almost impossible to unravel. Hans Haacke had it quite easy back in the 1960s when he could trace back a Museum's funding to a certain group of individuals and companies, that's very hard to do now. I worked with a public institution recently, a PPP (Private Public Partnership – is that still technically a public institution?) and at one meeting there were 15 different representatives at the table from various private subsidiaries and franchises, that all had to agree on the project.

But like I said this is always context specific, sometimes it's the commissioner, sometimes the marketing department, sometimes the curator, or the public that tries to control the outcome. Each project is always a social process, and the more you become involved in the process the harder it becomes to step out of it.

From trying to work through and experience these processes I am beginning to think that it is less and less likely they can really work in any positive way or in the terms that the commissioning agency or their funding bodies still believe or imagine they work. It's one of those Kafkaesque circuits... . In the UK there is a culture of evidence based policy making – set up by New Labour – which requires public institutions to make demonstrable contributions to government objectives and to meet specific strategies. This culture has now seeped into other institutions, I think. I cannot prove this but it seems evident from my own experiences. And like I said the charities and institutions I have worked with get their money from a huge variety of places so it's quite hard to unravel these tangled money threads.

One of the main reasons I accepted certain commissions was not to see them realised – I began my career making small models and diagrams that critically addressed and parodied these kinds of activities – but to experience the process of the commission and to understand how they work and what their limitations are. But like I said they turned out to be way more complicated than I imagined or perhaps how they might be perceived from the outside. In the end it's usually not worth doing – financially, practically or symbolically!

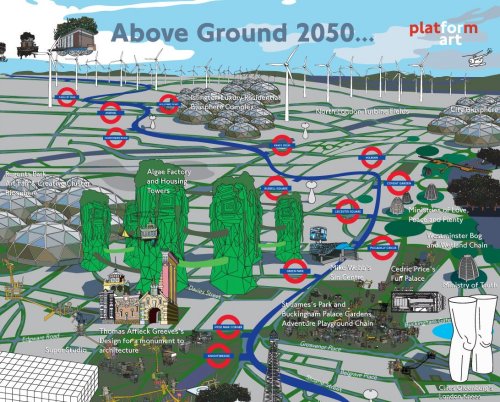

Image: Nils Norman, Above Ground, commissioned by Platform for Art for Transport for London

Is it possible to harness the many-headed hydra of urban regeneration as a means to realise a meaningful transformation of the urban environment?

Yes and no, it really depends from context to context, project to project. I have only been involved in one major scheme, and that was in Denmark, where I was able to change the planners master plan through unique social circumstances. That project, officially completed in 2006, is now being transformed by the residents independently of the local authorities and I am in contact with them. But from my experience, the amount of compromise and negotiation is not compatible with how artists have traditionally been educated. The planning process is usually extremely complex, and the idea of artists making changes is pretty much a myth, even the critique of artists being able to make changes is slightly misinformed, but inserting a critique, is, I think still necessary. Architecture and urbanism has no real tradition of institutional critique.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com