Interview with Alberto Duman

Alberto Duman's highly conceptual public art practice is less about the placement of art works in public than about subjecting the invisible processes that surround the selection and siting of public art to an expanded form of institutional critique. Josephine Berry Slater and Anthony Iles interviewed him on the strange pleasures of serial rejection

JBS: Where does your work take place and who gets to experience it? How does it engage its public or audience?

AD: You think this is an introductory question, but I think this is a final question and actually I had 2 types of answers because what struck me is the use of the word engage. As we know very well, engagement is a key word in everything that we and you have put under your research objective in terms of criteria, targets and evaluation of the works produced. If we talk about art in public, engagement is a tainted word because it is certainly a very interesting potential quality of a work. As it is postulated these days that without engagement there is not a work. But that's because you have to say what you mean by engagement and exactly what it is. So, I'm going to give you a little summary of what I think it is, and why it's very important, because everything to do with the Blair era in terms of cultural policy resonated with an inheritance of left government and their policies to do with art. These tended to justify art in a very useful manner. So art is important not as a kind of philanthropic, generic, transcendental whatever you want to call it - the sublime excuse for art let's say - but because of what it does and how it enacts its mandate, its mission. And so to talk about engagement in terms of public art, means to say you have to define this word ‘engagement' as more than spectatorship. It's supposed to be a form of relationship which is more than just the so-called passive. Now this is my first problem. I disagree entirely with the idea that spectatorship is passive and with the fact that an object, because it's mute, cannot engage. Or cannot necessarily bring a form of engagement other than the one of the workshop, installation or participatory work. So we talk about engagement in that way, it is a problematic thing, because engagement is definitely a part of spectatorship.

Image: Alberto Duman, CAD mock-up for Demostaph, 2001-5, a monument sited at the confluence of the Grand Union Canal and the river Soar, in Leicester City centre

I'm saying that because I have developed in the last 10 years in a transition from the moment when objects were the way to do public art because it was a sculptural tradition, into a situation where everything but the object is the way to do public art. Whether it's going towards the architectural/pavilion type or the generating a little market in a field as a kind of re-enactment of other forms of entertainment, all kinds of activity can be branded as art. I'm not advocating a return to the object - which is very important to say. However I dislike it when the so-called progressive forces of art tend to encapsulate the way forward in one direction only and somehow strait-jacket the imagination of the artists to say what is worth pursuing these days as part of an ongoing discussion, almost an accumulative scientific discourse is this and not that. So, no objects thanks very much, objects are obsolete, objects are not engaging, objects are silent and how could you possibly relate to an object? We're talking about people who have no artistic education, and I'm thinking you're talking about the wrong object and that's why you're discussing it in these terms. And I'm going back to that, I know it sounds like a long way to start from, but it is central and crucial to the way in which Labour's cultural policies have tried to encapsulate the field and say, ‘without engagement there is no public art'.

JBS: So returning to engagement, when you say there is something specific that goes beyond spectatorship, how do you understand this particular spin on engagement which, historically, has a political significance?

AD: Totally, in fact, that's exactly where it comes from. So we acknowledge that and the previous significance of engagement and spectatorship. I'd say my position is that it's very important that at any given time, there are no orthodoxies about how artistic practices engage. [...] What I don't like is an attitude for which there's a sense of a progressive obsolescence of previous forms of engagement which are the object and the onlooker.

JB: Disinterest as well, the Kantian characterisation of aesthetic engagement...

AD: Exactly. There are static sculptures which if placed in the public sphere would be a lot more explosive in terms of debate than a lot of so-called engaged art [...] And unfortunately there is a community within the art world that believes in the obsolescence of the art object, and sidelines it deliberately.

JBS: Have you experienced this in your attempts to get public art made?

AD: Well, I have had several times, a strong temptation to abandon certain paths, physical forms of sculptural engagement or activity, because its obvious that the trend seemed to be (although I think it's come to a standstill for other reasons which we'll discuss later), because it was clear, that the form of sculptural media, of hard sculpture, was perceived as obsolete. It involved a kind of expertise, of how to interpret these objects, which immediately instigated a sense of division between audiences.

AI: Does that mean, because I'd be surprised, that, say, engaging people in your work as spectators is enough for you?

AD: Ok, bear in mind that my point of departure, if I'm being polemical about this, is due to one specific reason; that there's a kind of trajectory in which public art has become very popular. And it's become popular partly because it's been driven towards becoming a dead conscience, the conscience of development.

JBS: Like the Percent for Art policy...

AD: Yes. By being ephemeral, discursive, relational - all that terminology which means I will not make a physical object - on the one it has tried to escape the shackles that relate to making physical objects. On the other hand it has, in a sense, divorced the possibility of making something which is longer lasting than the meeting, than the happening, than the performances, than the engagement with the citizens of that particular area.

JBS: And perhaps an important part of that is that the people who then get to experience that work after the fact, if it's only that you can experience it through reading about it, or through documentation, then really those people are already within the art world - as art historians etc., or people so inclined to research it.

AD: Exactly, and you need to get hold of the documentation, the books. Well, ok, there is a double game taking place here. On the one hand, the forms of public art that have become very popular in the last few years, are the coming together of very opposite and unconnected strands: the development of art in an outdoor or public situation, and the management of public art as somehow palliative care for a development that has to happen anyway, and what we're doing is adding the art as a form of public appeasement.

JBS: But wait a minute. Aren't the preferred corporate forms of public art more sculptural, more hard?

AD: Absolutely. Which is why, the argument of distancing oneself from sculptural form has had a footing. But at the same time, even the possibility that a piece of public art, that exists physically, is meant to last longer, seems to assume that that type of work hasn't got any critical potential. And it's been the side of the art world producer that has disenchanted itself with the hard object because the sculptural trajectory that was going parallel to the public art development caught up with the mainstream of public art at the point in which the object was already a very dubious object to discuss in sculptural development. So there's been a strange wonderful offer of say look, the tradition you want is not that tradition, it's the performative tradition.

JBS: So if you can't tell us anything about your art can you give us an example of what you're working on right now just concretise what you do?

Image: Alberto Duman, from the photographic series Waiting for Nostalgia, shot in Sharjah, UAE, 2009

AD: I'll tell you what I've been working on, and which has just been delivered to the commissioning agency and I'll tell you the situation in which I've delivered the final product which is very interesting. This is to do with the Spitalfields public art programme. There's been a sculpture prize for which I submitted an entry last Tuesday. It was exactly the day that the Climate Camp contingent arrived in Liverpool St., in front of the RBS, to picket and block the entrance. Of course, clearly in relation to the role of RBS in the (financial) crisis and the way in which Spitalfields itself is very ‘edge of city' which means there could be possible expansion, there is Shoreditch Studios, everything just comes together.

JBS: Site of trauma at the G20...

AD: Yes, exactly. It's the perfect location, perfect moment and of course it was quite symptomatic that at the moment I delivered this proposal - I delivered it to Hammerson the developers - and these are the developers who are in a very bad situation with the whole artistic and cultural community of Shoreditch, spearheaded by the signature of Tracey Emin and some others, to do with The Light, that beautiful building which has been for a long time one of the posts that delimits the boundaries between the city and Shoreditch proper, marking a clear cut difference. So, the interesting thing of delivering a proposal to Hammerson and then witnessing the Climate Camp parading in front of the RBS put me right straight about my position as an artist and its ambivalence and its mish mash of impossibilities of being a straight warrior for either one particular party or another. And instead being this strange meeting place where, with a proposal, I can infiltrate a body like Hammerson, and at the same time go there and participate in the Climate Camp. I'm not claiming special status in this, and the reason I'm talking about this is that your question leads to this very problematic ambivalence, and the fact that in a way, if I leave the camp of this big commission to the guys who are made for it - a specific type of artist - I abandon the chance to enter into that process, which is very important, and even speculate on the possibility that a certain group through subterfuge, through outright lies, just get into this thing. Ambivalence sounds like you're a two faced guy, but it is the position of public art. It has to be because it cannot decide on the sites for itself, in terms of placement, permission. Let's face it, public art always needs permission from someone else, unless you're storming the palace, ok, and that's another type of public art.

JBS: Maybe there we can ask, albeit that you're not storming the palace, and that you have to do it through a process of negotiation and compromise one might say...

AD: Yeah, yeah, the word ‘compromise' I don't find it tainted.

JBS: ...do you feel obliged to reveal the conditions of the production of the work?

AD: I think a lot of people have problems in interviews telling it straight, because if you're operating most of the time under some kind of camouflage then the so-called moment of truth is perpetually extended forward, because if you want to keep practising you have to present some kind of neutral face where you're not specifically taking a position that would immediately open the perception of what you do as already taking a particular part in a discussion. Let's not forget that public art is very often used as another means of negotiating for regeneration agencies in areas where some form of social conflict is happening, or has happened or is about to happen, it serves the purpose of negotiating between parties. It has a political function in the sense of appeasement to some extent. And this is where the problem starts. Imagine the public artist as the UN envoy in a war zone; he has some form of political immunity but he's not politically neutral. He's trying to be, but by being involved he will take sides automatically. The artist, very often is called in with a fairly backward idea that art has the capacity to negotiate, be a meeting place, art is a space where differences are negotiated because it can transcend the specifics of the situation, of time and space. So under those pretences the artist is engaged by the very people - not by the people who don't have the potential to pay for his wage - but by the agency who has already created the conditions that are slanted in the first place, for which the artist comes to assuage some form of damage already done. So it's obvious that you arrive, and when you're an envoy you understand immediately who you're supposed to talk to, what you're supposed to say and what you're not supposed to say unless you want to be substituted or terminated. As would happen to someone negotiating for the removal of weapons of mass destruction in the wrong zone and who's taking the wrong steps.

JBS: So what makes you want to practice as a public artist?

AD: Well it's exactly that. Maybe I like the danger of stepping into a land mine and blowing myself up. In a sense I found the confines of the art world where you can do whatever you want because hardly anyone is going to say ‘Oh that's disgusting' in the confines of a gallery. But what I want to do is to be able to infiltrate the public space with ideas that are very unlikely to be found there at any given time.

So, to get back to your question about Spitalfields and what I'm doing there - ok, let's evaluate the situation. A) Hammerson, the developer of the whole area who has changed the face of Spitalfields across the last 15 years, radically, with lots of social and political conflicts with other parties, stipulates the terms of a public art commission that is to be situated in the midst of this environment that they created themselves. So already we have a tainted situation. Not only is it stipulated that the work will have to somehow be under certain terms - not offending this and that, just like most public art which is developed under the blanket of what's acceptable in public space, which is always liable to change - but anyhow we have this developer who has developed Spitalfields, has made it what it is now, radically changing it, and here I am taking part in this art prize. From the start I know I have to play a double game. If I really wanted to be honest, fully, I would just not participate in that prize at all, and that would probably be most people's choice, most people in the art world of a certain level never fill out an application form, it's detrimental for them, second rate artists do that, it's like ‘I get given the commission'. Second, they will not deal in any situation unless they are invited. An invitation already vouches that they want you. Now I'm not in that kind of position to be invited, and anyway the artists that Hammerson would invite are not like me....

JBS: I'm thinking of the red sculpture of Hawksmoor's Spitalfields church...

AD: Exactly. That's what's going. That's going away.

JBS: It's going?

AD: That's exactly the site I am talking about. So here I am developing this proposal and I know I'm treading on an incredibly difficult situation, a situation where even someone like bloody Tracey Emin, who is a columnist for some magazine [...] , anyway, she's campaigning and it's a contested area...

JBS: So you're saying that in Hammerson's eyes, even she is a radical?

AD: Oh yes, absolutely. So if you are a conceptual artist who pretends to operate in optimal conditions as you set the agenda, then no point in applying. But nothing in public art is straight forward. Because of course like in the public in any case, it is an overlapping agenda; you can go and stand on your hands, or upside down, or hang, and more often than not you're impinging on either the jurisdiction of a place, unless you're a circus act... So to get to the point, the way I propose this is a negotiation. The moment you enter into a competition with Hammerson it's obviously a compromised situation. But the compromise is exactly where public art should go.

JBS: Can you give us a concrete example?

AD: Ok, well it's what I proposed, which is a 10 m high - they want a big sculpture that stops the crowd - so I'm giving them that, but what the object is a blown up 10 m sign saying ‘Cleaning in Progress'. A yellow, tepee-style sign, you can walk under it and whatever - which signals cleaning in progress. Now you don't need me to say anything, you know exactly what I'm getting at. Now, the problem is this - I have tried many times to do this kind of operation, so far without success - I think my chances of succeeding are very slim. I think they are going to put me in the final because it's a funny piece, it's colourful, it creates a good thing for the commissioners to show they have diversity, but they're not going to commission it.

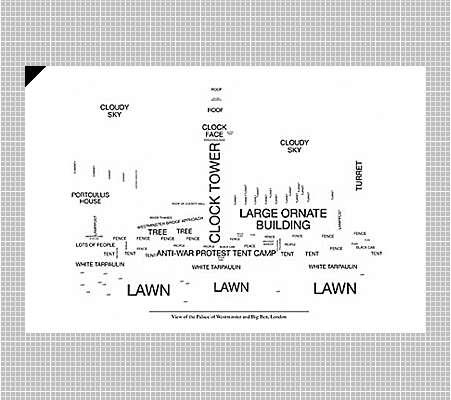

Alberto Duman, from the London Postcards series, silkscreen prints, 2008

JBS: And also, Claes Oldenburg has succeeded with the same over-scaled objects...

AD: You hit it right on the head, in my writing of the proposal, I have to write it in such a way that I have at least a chance of being accepted.

JBS: So you put yourself in a canon?

AD: I wrote it in a completely different slant from the way I intended the proposal. I said, I'm interested in temporality and permanence, and by extending the temporality of a sign into a permanence I'm making the rest of it appear blah blah.

JBS: So you didn't mention Meirle Laderman Ukeles...?

AD: No, I did not. So this tactical situation where you have a moment of possible disruption where a) either they realise immediately or b) they think it's big, it's funny, you can rest under it - the individual scaled down by the proportion of the regeneration to a germ can hide under the sign of cleaning in progress, and somehow shelter from the sanitising event. So this for me is a paradigm of the way I've operated for the last 5 years or so. When I enter a big commission, I realise that I have to masquerade. I don't have any problem with that. I think masquerading is a very good exercise for the development of your work, and I realise I end up doing the work that I love because it's very problematic, it's two-faced in a way, and this ambivalence which is something that, if you want the trust of someone and this person is ambivalent then they leave you asking - hold on, do they mean it? don't they mean it? And this is interesting because the meaning it and not meaning it plays on the strength of the sculpture, that once it's out there, it could split the audience between those who grasp it and those who don't. And you could say that the message is in there. So travesty somehow has to come into place, and when you operate at that level with the developers responsible for the purging of everything that was Spitalfields, then you either apply or don't. My interest is in applying and forcing - even just to shove in front of the faces of the judges - this object that is odd, and having them ask what's he doing. And this piece, which is a metal construction, it's a permanent piece, it makes the rest look impermanent - the temporality of the space, which wants to be infinite, is turned into what it is, which is not eternal at all. The next generation is going to tear it down - maybe even the same agency. Imagine if this financial crisis extended and really goes deeply... but anyway. But this piece is paradigmatic of the way I try to situate myself as problematic to the point that you nearly give up that kind of practice. But far from wanting to hide myself away in the gallery system ..... what I'm always doing is always betting. For the last 5 years, the majority of my submissions are a bet: let's see if they stop it, or if it manages to go through.

JBS: So how many times have you won?

AD: Probably one in not such a relevant situation. I don't know why it's happening. But the crucial moment that I always imagine is the jury saying: he's not serious, no, he is fucking serious, I can't believe it - ok what are we doing with this because it's well presented, he's got a good CV, so we have to consider it. So I suspect they'll probably put me through to the next stage where you get the money to develop it, and because it's a funny piece they'll want to put me in their exhibition.

JBS: This is reminding me of Roman Vasseur's description of the ‘sensuality of bureaucracy'.

AI: Yeah. I'm interested in the fact that it's public art where the artist and the agency ostensibly care most about the public, but where the dialogue is between the artist and the commissioner, and there's this sort of fear of the public.

AD: Yes, and they use subterfuge as well. The thing is that whoever sets up a public art commission needs a consultant, to back themselves up. And the expertise that the consultant offers is the language in which the proposals are written, the call for artists, the rules. And very often it's just cut and paste... But the interesting thing is that, it's like this, you apply for a job, and you know you won't get it - but I've done that like with the job for the Head of Sculpture at Goldsmiths - but I have applied several times because I wanted them to read what I wrote, it's like a test. How can you test institutions if you don't engage with them? I know one position that is very easily taken, and it's a purist position that says, ‘I‘m not going to apply there, it's a bunch of wankers, they're corrupted from the bottom to the top. Why should I give my expertise and my talents to them? They deserve something like the public art that they've got, which is not that great.' But imagine that you had a critical mass of artists that apply with great stuff, then they can't ignore it. They have to take it into consideration even if it overrules the reason for which they thought they were there or even if the head of the developers is trying to steer them in the other direction. But remember, the jury is there, it's like in a trial, and it has the potential to deliberate. It's like Twelve Ugly Men. You have to consider that there is a potential for those 12 ugly men to get into that room and do, once in a blue moon, something that shouldn't happen. And the developers in order to stop it will have to go against the jury and then he'll find that the jury might blow the top off what is going on with this commission. If you don't test the boundaries of these identities, and you allow them to develop through the usual crap sculpture you find all over the place in those conditions, and then the only terms of judgment are either Richard Serra's sculpture in Broadgate or that fold-out house in Spitalfields. There's got to be more than that on the plate. What I'm doing, possibly wasting a lot of my career time, I'm putting my stuff on a plate where it might or might not be seen, might be totally side-lined, but it's very important for me because I've always found a mission in failing.

JBS: I was going to ask you whether, at a certain point, your need to get a public artwork made - partly due to all that effort, all of those applications, and plans, and the desire for one of your ideas to finally see the light of day - whether that would win out over your interest in doing it the way you've just described and your attempt to insert something radical into an essentially conservative process? Whether, perhaps, that need will overtake, or whether your practice is more of a conceptual practice which is about the negotiation, the game that happens behind closed doors, the putting in front of judges something that will cause them to chose you by some ruse of logic or humour? What is the more attractive pole of your practice?

AD: The situation is not that simple, because the situation is not just as simple as bad boring guys sitting on the juries, clever work coming in. Sometimes the negotiation is much wider than that. I don't take sadistic pleasure in failing my submission even though I know already...

JBS: You mean masochistic?

AD: Yeah, yeah, in the sense of saying that I really like pain and I like to inflict failure on myself on a daily basis. There is also on the other hand situations in which there are bodies that I apply to that might be so well informed in their capacity of buying criticality, that they might be very prepared and not at all phased by this sort of thing, and I don't really pretend to think that they are just thick, because developers are not thick at all, they are actually extremely clever often much more clever than the artists who apply. But I have developed this sense of losing to win, the sense of being there in the selection process with the point made, because at some point - I think all of this started in 2001 when I was engaged to do a piece in Glasgow and I didn't get it - there is a sense in which this kind of seemingly nonsensical attempt of failing and succeeding, as if the failing would prove my point more than the success, is a testing ground. Up to a point I thought I'd have quite a straight career, I had a sequence of successes with this sort of thing, but the shift came in about 2002/3. What happened is basically, I realised that there were all these mechanisms in place which I hadn't quite realised and since then I kind of changed the sense by reconfiguring my participation in this kind of thing, not by giving up. I really wanted to be present in the process. But I also realised that also I was prepared to lose much more so than winning.

JBS: How do you live from losing?

AD: Well that's the thing, it's diversified [...] when the trouble started I realised that things had to be reconfigured. So, a bit of teaching here and there, and other work which has nothing to do with art. And a sense that, through the loss of this innocence, I actually tap into exactly what it is about, all this public art construction; the way to win is about having the potential to lose at any given time.

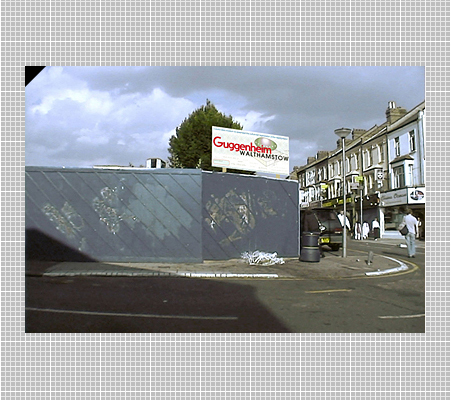

Image: Alberto Duman, Guggenheim Walthamstow, 2005, 'a hoax presenting us with the possibility that the "Bilbao effect" might visit Walthamstow and work out its tainted magic...'

JBS: I was interested in where we stand now. If a lot of the boom in public art can be related to the retail/real estate bubble, and the brouhaha about the creative industries that seems to be disintegrating in front of our eyes, where do you see public art going in the next 5 years, do you see a real sea change coming?

AD: Your question comes as a consequence of the ongoing financial crisis which seems to have caused more than a ripple on all the mechanisms that subtended to the potential for public art to exist, because of money flow, because of percentage, organisations all of this. And that's an if, because we can already see how the haemorrhage is treated in a very different way at the moment. There's denial, reports every week sent out that there's 0.2 percent based on last year's 0.5 percent which means that we're recovering and that we're going to be quite alright.

JBS: A friend of ours googled on ‘green shoots' and found that since the crisis began whenever that technically was - since the collapse of Lehman - that from at least the beginning of 2009, there have been reports of recovery week on week.

AD: Well that does not surprise me at all. We're talking about an environment - the banking and investment environment - which is not based on fact but based on dealers. So everything can be made and unmade. So that's the context in which we operate. But I was reading the other day, that there's still a lot of budgets that are being spent, that were earmarked before. If you look at magazines, Art Monthly and whatever, something has happened big time but there are still a lot of commissions coming out. Now certain budgets were earmarked and they're spent now, and other projects are in trouble like the Tate Modern extension.

JBS: Well the museum bubble in itself has actually destroyed the viability of a lot of museums.

AD: Yes, the public art bubble was based on a percentage of it, and the bubble before that was that of museum and gallery construction, all over, as if every quarter needed such a development and many are being shelved now. But what's going to happen? Public art didn't start like this, it existed long before these big budgets.

JBS: When you say public art, are you talking about modernist, post-modernist?

AD: I mean from the '60s onwards. Public art to me begins with the commissioning of the Chicago Picasso, '62 something like that, meaning artists of great reputation commissioned to make a big gesture in an important part of the city. That is at its highest level, then you get into all these other configurations, so if you're looking at that kind of thing, then... well I'm really curious to know what will happen to the Ebbsfleet commission. You could say that the reduction of the traffic in that kind of environment could bring a further conservatism, but one that won't affect the output in the way you might think it does. It's the same as thinking that ‘Ah, when the easy money is gone, those tossers in their Porsches are not going to be around any more either' - but there's going to be tossers with nothing in their mouths that are going to be doing as much damage as those with the Porsches. So there's a mythology of certain groups who expect the crisis to extend their personal ethics into the public environment and somehow clean it up.

JBS: A lot of people are celebrating the age of austerity and the impact it's going to have on art because they feel that it's been corrupted by money, and that the bubble in the art market has meant that money and art have become inseparable; we're hearing it from the likes of Claire Cumberlidge and Alan Yentob - and it's interesting that it's echoed around the place, the idea that we're going to get rid of the flotsam and, as you say, enter the age of an expanded ethics.

AD: The opposite theory is the one of critical mass. If there was public art everywhere the accompanying discussion about public art, what it is and what it does would render its mechanisms obvious. It's no longer a specialised thing. So you could say that the critical mass could produce an awareness and a sense that when the game is clear, the cheapest games lose out, the cheapest items don't sell anymore. You start to produce a natural market in which self-selection develops; it's the competitive market idea. So that, in my view, was starting to happen, with the huge traffic of public art - people started to be very curious about it who never knew about it before, started to question it a lot more. [...] And then suddenly this reduction at the moment when most sectors were starting to get educated about it, and the sellers and peddlers could no longer play cheap tricks but had to up the ante a bit in order to convince people of the value of this. And now, it's going to go down again, and lots of agencies are going to collapse like the Claire Cumberlidges of this world ... lots of people who were making easy cheap stuff on a repetition, sausage factory basis will disappear. So sometimes it's healthy for a specific market to have a big slap in the face and say wake up, you're flying high where you shouldn't.

JBS: But that doesn't apply to television.

AD: Because it's a primary output. What you must understand about public art is that it's dependent on finance. Because it works on percentage. The money doesn't come straight from public art, it's a percentage. That's why it's dependent on the crisis as much as success. Why was public art everywhere and anywhere? Because the market was up. So in a sense, why should the public art agencies should bother to criticise anyone when actually the more there's speculation the better they do in business. They're highly dependent on their client, which is why we want to ask the public art gurus who run these agencies, ‘where is your allegiance to me or to them?' They are your client but who am I? They pay your fee, and you pay mine. So we're interlocked in this relationship. There's no such thing as independence [...]. The interesting thing for me in public art is not that you're operating in a vacuum, like in the gallery, but that it's exactly that - that everything is compromised. Not even a developer can decide outright what they want to do. There's always going to be some form of agency that will not allow anyone to have their plans realised. And that works for the top guys as well as the small guy who's throwing a picket in front of them. There are of course huge disproportions in effectiveness and in potential. That is exactly why I keep applying to that sort of thing, because there's still a doubt that to disengage would be more wrong than to engage, even in a corrupted environment.

JBS: Can we end with your thoughts on Anthony Gormley's latest artwork - One and Other in Trafalgar Square? What were the most symptomatic elements in that work, or its significant moments?

AD: I will not comment directly on that work, because I want to start from another side. I find it hard to see the work for itself - because in 2005 in Leicester I made a work which was very similar. Several times I wrote to the people who commission for the Fourth Plinth to say: look you probably don't know me because I'm not anywhere near Holy Anthony, but I've done something lesser (which finished in 2005) which is also a plinth which people can occupy for a certain amount of time, without any scheduling, or any parading of this sense of importance of the individual. When it's paraded in that way in such an institutionally controlled and scheduled way it loses almost entirely its ambitions to be an open-ended work - and in fact it becomes the province of exhibitionists, publicists, it's probably done a lot for any causes, charities. In a sense he also had a lot better engineering to work out the health and safety issues which we struggled with in Leicester where the piece was sited on top of a mound made of the rubble of previous buildings which were then landscaped in that way. And on top of that mound there is a plinth which is funnily enough modelled on the one in Trafalgar Square - which is the one I used as a reference and with a stepped access. But of course we didn't have a plinth there, we had to make it...

JBS: What was the work called?

AD: It was called Demostaph, as in Cenotaph. In the sense that it's trying to be a parade of democratic process - you can go there, you may have to fight to go there, but you don't have to ask anyone's permission. You can go there, you can say what you like, it's in your interests or not, nobody might be there... I took it as an example of how we can reform, at any given time, from rubble a sense of real democracy. The plinth is all made of rubble - recycled aggregates from a local business, they donated the material. It's cast so that, once it's all polished, it shows that it is an aggregate of rubble. It meant a lot that it had this material quality of rubble - where you could recognise a teapot of what have you.

JBS: Other shades of Gormley - and his Wasteman. [laughter]

AD: If I may say so there are shades of Gordon Matta-Clark who first worked in that way, compacting waste in certain forms. But for me that was important because it had a real sense of participation and access to a certain place where you can speak your mind or do what you want to do under public scrutiny - it has to come from humble beginnings in a way. It has to come from the debris of lots of other things, and be reconstituted, held together, temporarily, and then someone can go on top - and these are the conditions of permanence that democracy should always remember.

JBS: Is there something about the fact that there was no crowd assembled, or most times wouldn't have been - is it a mockery of public address?

AD: I didn't intend it as a mockery of public address at the time. I intended it more from the fact that the small hill on which this sculpture stands is made of rubble aggregated and covered. [...] The fact that I then made this thing on top out of rubble as well on a hill where there's not much traffic, and with a cement factory there. It stands on an island in between a river and a canal which are going in opposite directions - I found the fact of the water confluence and these opposite directions, this strange regulation between a river and a canal interesting. Also, the fact that often institutions seems to be elevated on something - but this is like a parliament hill of rubble. But this is to say that everything should start at that level - the aggregations of what has no value into something that has value is a model for politics.

JBS: As is the disavowal, the covering over, the sweeping it under the carpet.

AD: It is - this mound was made simply because there was a lot of rubble and what did they do?

JBS: Gentrified it?

AD: Yeah [...]. And I always had an interest in waste for obvious reasons.

AI: A lot of the foundations for our parks are rubble.

AD: Parks very often are parks because they can't be anything else. They're just dumping grounds, like Lee Valley.

JBS: Mile End park...

AD: Very important to remember this exactly because of the Olympic site, and all these ideas of the water city which are often sold and is probably more like the ‘trash city'.

Alberto Duman <albertoduman AT yahoo.co.uk> is an artist and University lecturer based in Hackney, London since 1997. He has received public art commissions and held residencies across the UK and Europe and has been a visiting lecturer at the University of Wolverhampton and University of the Arts. He is currently teaching Urban Studies at Middlesex University.

Recent projects include: Decoder (2009), for the Sharjah Biennial 9, UAE, London Postcards (2007-ongoing), England & Co Gallery, London, Guggenheim Walthamstow (2005). See, http://www.albertoduman.me.uk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com