This Infant Earth

During the 1980's Dr. Jacques Benveniste, an immunologist and medical researcher, performed a series of experiments designed to ascertain the medicinal efficacy of homeopathic remedies. At the time, it was widely believed by the medical establishment that any curative powers associated with such remedies were directly attributable to the placebo effect.

§§§

For Slattery Lovechuck, it was the first morning of the downshift period. Morris, with whom he ran parallel schedule, would be in for the next four days, and relief would be on night shift. He had plenty of plans, all of which were now useless as he'd been woken that morning by a heavy dose of 'flu. His throat was wire brush raw, a discomfort which was nicely accompanied by the steady throb of a headache so intense that he could swear he experienced it viscerally. Groping his way to the bathroom, he switched on the WC and accessed the Benveniste chip. He was trying to describe his symptoms - rather slowly, as the computer had not been programmed with the patterns of his voice when hoarse - when it filtered through from the distant spiral arms of his aching mind that he was all out of distilled water.

"Fuck. Shit. Fuck!!" The WC chimed out that it did not recognise the command, and Slattery told it to shut up and stand by as he staggered back into the bedroom. There was nothing for it but to head out to the shops. To load the coil beaker with tap water was to tempt fate; it contained too many random impurities and there was no predicting the e effects that might be produced when these combined with the requested electromagnetic signature. You could take a chance . . . just like Slattery had done that time when Joan had invited herself over for the evening. They'd dialled up some MDMA solution and settled in for a night of exploratory passion. He'd used tap water then, because it was late and he didn't want to brave the streets. Four hours later they were still taking turns to use the toilet. Even Slattery Lovechuck was capable of learning from a mistake like that.

He went into the hallway and fumbled for the stair release.

"Good morning, Mr. Lovechuck," the barometer wined in vacant tones. "The temperature this morning is twenty-three degrees, and there is heavy rain throughout the Reading area. No change is likely until late this evening. It will be a damp day for the entire British Isles, except for the People's Republic of Scotland, which is still enjoying continual sunshine. Don't forget your umbrella!" Slattery cursed the machine and pulled the umbrella roughly from the antique coat stand. The stand was a possession of which he was particularly proud. He had found it in a junk shop years ago and had recently discovered that it was quite valuable. The brolly popped open in his impatience and unbalanced a vase which stood adjacent to the stand upon a small table. Slattery watched, frozen, as the vase teetered and then fell, rolling across the plastic veneer and onto the floor, where it split into two neat halves. A translucent jelly of saturated crystals popped out and wobbled on the carpet. The petals all fell from the lilies which poked from it. Slattery gazed at the scene in disgust and then wrenched the brolly free from the stand, snapping one of the ribs from its housing as he did so. He stormed out of the house rubbing his temples, and left the stairway extended into the street.

§§§

Benveniste's results suggested that homeopathy worked in a quantifiable manner by exploiting the "electromagnetic signatures" of drug compounds. The homeopathist alternately shakes and dilutes a solution of the drug, and it appeared that this shaking stored the drug's "signature" upon the water in which it was dissolved. Hence the apparent paradox that the greater the dilution, the stronger the remedy. Benveniste succeeded in transmitting the signature of a heart drug into distilled water via an electromagnetic coil. The• water, which had never come into physical contact with a single molecule of the drug, had the same effect upon a rat's heart as the drug itself. When the water was passed through a powerful magnetic field, this effect was removed. It seemed that H20 could function like a recording tape for other chemical compounds: by storing their signatures it could mimic their medicinal effects.

§§§

The barometer, whilst irritating, was not wrong. The rain was Magritte rain: straight, black and unrelenting. It fell from a flat grey sky that seemed to hover about three feet above the rooftops. Heavy with filth, it left dark streaks on pale clothing and ran in glinting torrents down the pavements. It's greasy eddies caught the eye. Slattery cowered under his heavy-duty rubber carapace, wondering when he'd get the chance to fix that rib. The brolly had been a recent purchase, and it was supposed to be an investment - ultimately cheaper than continually buying the thin nylon ones that were rotted to shreds in a couple of weeks by the acidity of the rain. He reached the corner and waited for the traffic to back up so that he could dash across the road. There was no point in taking the underpass, which would already be knee-deep in water. The misty damp light of the street oscillated from the zorby glow of the lines of halogens and neons; he could see the tall numbers of the 7-11 standing amongst them, fifty meters up ahead.

§§§

Beneveniste was ostracised by the French medical establishment, his laboratories closed down.

§§§

"Is that all?" The attendant inserted Slattery's card in the machine and began to click up the five gallon drum and the packets of soup that Slattery had dumped on the counter.

"Yeah, er no, er, a pint of milk, one of those loaves of bread, the brown one, and some of these." He pulled a handful of vitamin sachets down off the counter display. The attendant looked at him. "I'm ill," said Slattery, taking back his plastic, and sloped out of the store, listing to one side under & weight of the water.

Outside, the rain steamed off the hot pavements. He trudged through the miasmic stench, breathing shallowly and avoiding the puddles. Dr. Foster went to Gloucester, in a shower of rain. The old rhyme sloshed into his head, and for a moment it cheered him up. He pictured a comical man in a black top hat marching angrily down a country road, with a single cloud wilfully pursuing him. All around the sun shone, and butterflies and birds looked on with glee. He stepped in a puddle . . . A trolley bus skimmed past, and sprayed Slattery with water ... right up to his middle . . . the plume of water had found its way into the top of his galoshes and soaked through his sock; it was already beginning to sting ... and never came home again. On recalling the end of the rhyme, his good mood evaporated and was replaced with a feeling of unease so saturated that it submerged even the itching caused by the moisture in his boot. He came to the foot of his steps and hurried up them, glancing nervously at the sky before ducking inside. He took of his socks and galoshes and put them into detox before returning to the bathroom to download the drugs. Now he came to think of it, he couldn't remember seeing rain this bad before .. .

§§§

The human body is approximately seventy per cent water.

§§§

He had been back over an hour before he discovered the priority message in the e-mailbox. The anti-cyclones inside the surface of his skull were by this time somewhat equalised, but solids and caffeine were still out of the question, so he'd taken a coolpac of carrot juice and retreated to the VT room to watch Gaia News. A glut of news servers like Gaia ("All around the globe, all around the clock") had been spawned by the low-cost high-throughput economics of current affairs scheduling, and together formed a kind of world wide current affairs soap-opera to which most of the population were addicted. The previous afternoon there had been a third coup in the Ming Soviet and forces were being amassed along the border with New China. CNN had managed to pass a satellite through the Ming 0-zone during the night without getting it shot down, and the pictures of the troop movements were booked to be the morning's hottest event. But as soon as Slattery switched on, his VT auto-dumped the alert message from the Weather Centre all over the screen, rendering the already dubious satellite pictures totally indecipherable. He read the message and sighed. The various annoyances that had been mounting up throughout the morning slowed and coalesced. finally solidifying into resignation. His day had just got immeasurably worse.

§§§

The modern Benveniste chip was developed around the turn of the millenium. It simply stores the electromagnetic signatures of various drugs and transmits them into distilled water as and when required via an electromagnetic coil. The technology was incorporated into the bathroom Water Computer, or WC', which had become a common addition to Occidental households by the early years of this century.

§§§

Slattery was a "Weather Prediction Technician". He worked in the grey area that lay between computerised data interpretation and computerised data collection. On pessimistic days he would generalise about the various tasks assigned to him as falling into one of two categories: those which the machines hadn't been organised to do yet, and those which no one else could be bothered to do. Once he had been a programmer, but now the vast majority of all new software was "grown" in virtual ecologies, and he had been lucky to get this job at all, even though it was essentially a servicing position. "Weather Prediction Technician" was a glamourised misnomer, a small part of a large plan to bolster the Centre's self-confidence. Ever since Lorenz's work had gained widespread acceptance back in the 1980's prediction was no longer Reading's job. That was done by the Global Network Computer of which Reading was simply a node, albeit a prestigious one. The machines managed to predict with ninety percent accuracy five to six days worth of weather patterns anywhere on the planet, and the game had pretty much stopped there. To ask for information of the noumenal zone between this time-scale and that of the broad seasonal regularities was to ask a non-question. In empirical terms, that area didn't exist.

"You schee, weather ish an emergent property of the planetary water schlycle," Slattery would spout drunkenly at dinner parties, whilst trying to impress upon some prospective sexual partner the enormity of the skill required for his own particular "seat-of-the-pants" brand oftrouble-shooting. "And ash I'm shure you're well aware, the mosht shtriking characterishtic of a non-linear shystem such as the water schlycle ish its total unpredictability. Regular, yesh. High redundanshee, yesh. Predictability, managability, determinatenesshesh, no, no, no and no. The shimple eshenche of a nonlinear shystem is that it has no eshenche." And then he'd excuse himself, go to the bathroom, and be sick.

§§§

The development of the Benveniste chip broke the global monopolies that had been constructed by the trans-national drugs companies. Large scale financial upheaval ensued.

§§§

Because he left home at mid-morning the traffic was light and it only took him forty minutes to drive the five miles into work. By now his 'flu buffeted dimly against the glass wall of the drugs, and he felt numbed but capable. As he drove into the build-;no ha. Tervathered some of the sludge of his earlier bad mood. He wanted to be able to signify his displeasure at having his weekend ruined, and this required maintaining just the right amount of bile in his system. But he was caught off-guard by the atmosphere of controlled panic amongst the other staff. Usually, the Centre motored along without much more than a murmur, but today the halls sang with the rhythm of feet. Clack clack, squeak squeak. So Slattery satisfied himself by grinding his shoes in a childish and sarcastic counterpoint to the rhythm of efficiency as he made his way up to Room PR3. Which is where Clark, the sombre and officious security guard, had told him that he was required.

PR3 was a mess. Cables choked the floor, terminals and servers covered every surface, and seven or eight vast grey support screens lurched at strange and wonderful angles. The active wall at the far end of the room glistened with the silver blue patterns of what looked like a vast hurricane over the southern Pacific. Slattery decided upon a cheerful approach weighted to annoy.

"Hey Morris! What's up? How's Joan and the kid?"

"Having to rig up all the screens we've got in here and hook them directly into the network. Need real time animation of as much of the globe as we can get. Can't get this T26 to work. It's supposed to coordinate these three screens." Morris motioned to a clump of the ungainly forms teetering nearby. "We want Australasia, the Eastern seaboard and Antarctica up first." And nodding to the working display: "The areas surrounding that, basically." He ignored Slattery's second question.

"But I don't see the problem. So, big storm over the Pacific. Lots of floods in Bangladesh and not too tasty for Hawaii. The usual equipment should be enough to monitor it." But Morris had no time for Slattery's feigned urbanity. Beads of sweat were precipitating along his upper lip. "Well, don't ask me, friend. All I know is that you're to get these things hooked up and then report to the boss. Like, now."

§§§

Environmental scientists began to wonder whether this capability of water to store information might not be found in natural processes. A river, for example, would surely be rich with electromagnetic traces. Under the right conditions, could. these self-organise into coherent signals or resonances? Might rhythmic changes in this flux act as trigger signals for such events as the spawning and migration of fish? The excitement that such questions aroused led to a brief but massive boom in environmental research; concerns grew over possible unforeseen informational effects of pollution.

§§§

Bertha stood in her office. She was focusing on the displays projected before her eyes by the heavy tortoise-shell holo-specs that she wore. Continual situation updates reeled away in front of her, invisible to Slattery except for the faintest glint and residue.

"I presume you're familiar with Benveniste's work, Mr. Lovechuck?" She spoke his name as if she were reading it."Of course," Slattery replied,absent-mindedly. He couldn't understand what he was doing here, and knowing that Bertha's attention was divided he let his gaze wander around the small room. "At least, I remember what I learnt in school, if that's enough." Bertha did not answer, but turned her head to the side to reach for a cigarette. Quick flashes of tiny crimson paragraphs sparked up before her face, hung for only the softest instant in the ether, and then disappeared. She began to talk about homeopathy, about cell communication and compound information transfer in the mammalian body, about weather systems and self-organisation, about the memory of water. Slattery began to drift off amongst his own thoughts, recalling fantastic childhood plans for giant and baroque machines that could drag from rainwater images of the view from the clouds, or could access memories from the cores of the polar icecaps of the time before the humans came to earth. Dr. Foster ... He drifted until the silence intruded upon him. Bertha was glaring at him through her spectacles.

"Did you hear what I said, Mr. Lovechuck?"

"Er, well, not exactly, I'm afraid I'm rather tired, I haven't had a break yet today . . ."

"The massive reorganisation of global weather patterns that we think began early this morning is still continuing. That is why we needed you here today, Mr. Lovechuck. It seems that the weather system has become so overloaded with pollutant information that it as hit a bifurcation point. It is rather important that we monitor this as closely as possible. That is why you have been called in at such short notice." He was awake and he wanted to swear, but his mouth and throat had dried up.

"Did you bother to look at what was on the screens once you had set them up?" He shook his head. "Well, I suggest you do so now. You might find it interesting."

§§§

Between 2005 and 2025 a number of studies explored the hypothesis that coherent electromagnetic information might be found embedded in the planet's water system. The most promising piece of research took place in Tasmania, on mountain cloud formations, over eight seasons. But despite extremely high density monitoring, only a handful of recognisable compound signatures broke the background noise. The team concluded that any redundancy that existed would have inhabit scales outside of those accessible by the available instrumentation.

§§§

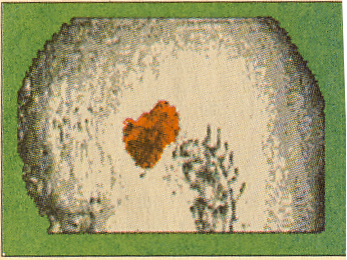

The walls of the theatre shone like a vast magic lantern, the series of frames displaying various aspects of the planet. The Pacific formation had remained totally stationary for over fourteen hours, which was unheard of. The first pictures were beginning to come in from ships and aircraft that were retreating from the area. They showed distinct plateaus of cloud covering hundreds of square miles and subsisting in variegated strata. There were giant thermal twists and vector currents, squalls and tornadoes sucking walls of water right up out of the ocean, dark and complex families of grey nebulae spinning at various heights and speeds. The increasing stability of the storm was made apparent by the satellite animations, which revealed its shape as that of two colossal cyclones with disproportionately large centres, joined together longitudinally. The eastern ran clockwise, the western anti-clockwise; vaporous matter of a dark and viscous nature streamed between them forming a vast figure of eight, a primal Möbius strip. Outer turbulent spirals occasionally gathered enough momentum to spin off on their own, living a brief half-life in the surrounding striations, until their will was garnered and absorbed by the licking current and resubordinated beneath the larger coherence. The Earth was unrecognisable.

In Reading, above the Weather Centre itself, the clouds streamed from west to east. Slattery left PR3 and found an outside window from which to watch. After a while he became aware of Bertha, who was standing behind him.

"It seems that reflexive thought is beginning to emerge from the flows of the planetary weather system. In a weak sense, of course." He turned and she fixed him straight in the eye. The flicker of the holograms had stopped, and he could see the tiny images of text glinting in her lenses as if they were reflections from a terminal positioned somewhere to the rear of his head. "What the consequences will be for us, I have no idea. I very much doubt that they will be favourable."

"Is that it?" he said. "Is that all you have got to say?" She smiled.

"The Hubble team has been carefully monitoring Jupiter over the last forty-eight hours. A major increase in activity has been detected in the region of the Great Red Spot. They have some evidence for directed signal transfer between the two planets. We've suspected for some time that Jupiter may be cognitive." She walked over to the window and looked up. "Perhaps the human race had a purpose after all, Mr. Lovechuck, although like all our little purposes we may only suppose its truth in retrospect."

"I don't understand."

"Why, to be the pollinators of this strange and massive new flower. To track material singularities and so gestate this infant earth." Her words sounded far too prepared, far too outrageous. She turned and walked away, and he followed her into her office. What shocked Slattery more even than the tumultuous event itself was that she seemed to be claiming credit for it. She reached her desk and turned her attention to some new piece of information, hiding her excitement behind the habitual professionalism whilst he tried to assemble some sort of pride, some sense that there was something to be saved. He stood there cold and she listed instructions to her machine in a low voice and his outrage ebbed slowly away. She said nothing to him, she just let him run his course. He stood there for a long while, feeling his being slowly dissipate until it was as tentative and fragile as the traces of the tiny red text of the holograms that left the briefest traces in the air as she moved about her work.

At length, she deemed it politic to notice him again. "Thank you for coming in today, Mr. Lovechuck. You have done a good job. You may go now. Return to your weekend if you wish." But Slattery no longer felt capable of taking such decisions. That prerogative had now been passed on to something very large and very far away, to some giant mill to which he was the merest whiff of fuel, to which he was the merest thread of grist.

THE END

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com