I Love You, Virus

Ian Morrison explores the rich social and political life of the new virus species The idea of computer viruses has been with us for over 50 years now. In 1949 John von Neumann’s paper on the Theory and Organization of Complicated Automata described programs that could replicate themselves and in 1950 Bell Labs created ‘Core Wars’ – a game where two programmers unleashed software organisms and watched as they fought for control of the system. It’s in the last few years though, that viruses have become headline news.

It used to be the case that viruses were spread on floppy disks. Then, as modems became more widespread, downloading one from your local bulletin board became increasingly likely. Now however, the internet offers an unprecedented opportunity for viruses to access our systems. The growth of internet email, in combination with badly written software and apathetic users, creates a situation where people freely send attachments with executable content. Users don’t realise the dangers of sending a word document or html file through email.

It’s not just naive users that fall victim to viruses. Cartoon heroines, the ‘Powerpuff Girls’, were infected by the FunLove virus when their DVD ‘Meet the Beat Alls’ was shipped unchecked. Although distributed on removable media, viruses like FunLove automatically spread between PCs on a local network. Warner Bros sheepishly recalled all versions of the DVD.

Although many viruses are simply variations on a theme, new concepts continue to emerge. It’s their adaptability that makes some of the more recent strains so dangerous. Take the SadMind worm, for instance. It affects versions of both Windows and Unix web servers, scans networks and attempts to deface servers. Thousands of websites were reportedly affected by the worm, including that of TV presenter Keith ‘Cheggers’ Chegwin.

Although SadMind is a worm, the line between virus and worm is being blurred increasingly by multi-pronged attacks. Recent media superstar, Nimda, also attacks web servers, but uses vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s Outlook software to spread without the user opening the attachment. This kind of technology allows a virus to pass through a firewall, attacking and infecting any local or Internet servers within reach. It’s no surprise then, that Nimda accounts for over 27% of viruses reported in the wild this year – even considering its release was as late as September.

Many viruses exist purely to cause havoc, hiding or deleting files, or sending private documents to people in your address book. They serve to prove a point, to demonstrate a flaw in either the software or the user. Others though, can be used to spread the political agendas of their authors.

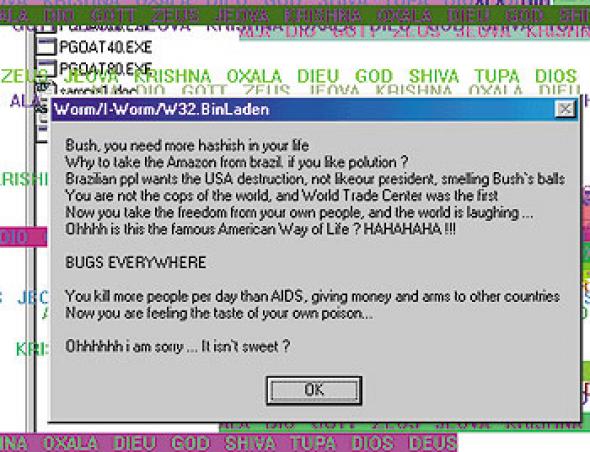

The ‘Bin Laden’ virus, correctly known as W32/Toal-A, is an email-aware virus that arrives as a BinLaden_Brasil.exe attachment. The MIME header of the email exploits a vulnerability in Internet Explorer 5 allowing the attachment to run automatically when the email is viewed, occasionally activating a visual payload. After deleting firewall and antivirus software, the virus then connects to the ICQ chat network and searches user profiles for terms including ‘history’, ‘friends’, ‘airplane’, and ‘orgasm’. It then sends itself to any matching victims.

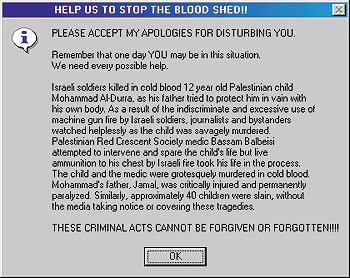

Back in May, a virus highlighting the friction between Muslims and Buddhists in Sri Lanka offered little threat to computer users. However, the Mawanella worm, named after a Muslim village, is yet another demonstration of malicious code being used as a political platform. It arrives as an email with the subject line ‘Mawanella’ and, if launched, forwards itself to everyone in the user’s address book. A message then appears describing the burning down of two mosques and one hundred Muslim-owned shops in Mawanella. Similarly, the Injustice worm disseminated pro-Palestestian messages and spammed a number of Israeli Government email addresses.

The virus threat is unlikely to disappear, and many will fall victim to it. However, as viruses continue to exploit and expose security weaknesses, users will perhaps get the chance to consider the importance of their computers, and whether it’s worth learning how they work. In that sense, I see viruses precipitating change; offering a reason to secure systems, and fixing a whole host of more serious privacy issues in the process.

Ian Morrison <ian AT darq.net> is a security analyst and founder of Darq Ltd, a network consultancy in London.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com