Fear of Flesh: An Anatomy of Modern Frigidity

With young people today caught between a world of advertorial eroticism and a reanimated liberal puritanism, Laurie Penny explores our capitalist erotic orthodoxy and asks what a genuinely sexual counter-culture would involve

Modern society cultivates a gleeful horror at the promiscuity of the young. Look around: pre-teens who should be drinking ginger pop and going on picnics are wearing thongs and listening to Lily Allen. Children delinquently rummage in each other's pornographic pencil cases. Even babies are now born with the Playboy Bunny image tattooed onto their eyeballs. Their fault, the salacious little sluts, for daring to look at the future.

Younger generations have always had to contend with clumsy data shoehorned into an adult agenda that smothers and misunderstands their sexual choices. In 1274, Peter the Hermit proclaimed that: 'the young people of today are impatient of all restraint [...] As for the girls, they are forward, immodest and unladylike in speech, behaviour and dress.' But in an age of easy public access to accurate statistics, 21st-century moral posturing has at least abandoned any pretence at factual accuracy.

In 2010, the British press pounced on a local health spokesperson's suggestion that online hook-ups might be linked to a slight increase in cases of syphilis in Birmingham. Within hours, this throwaway line had been transposed into lurid headlines declaring that the social networking site Facebook had ‘caused' a 2000 percent surge in the disease.i It soon transpired that the actual rise was far smaller (a rise from 10 to 30 cases in the area) and the connection with social networking staggeringly tenuous - but in the few hours it took for curious readers to do their own online research, the moral narrative had already been seeded, and parents across the country had yet another reason to fear and police the sexual behaviour of their children.

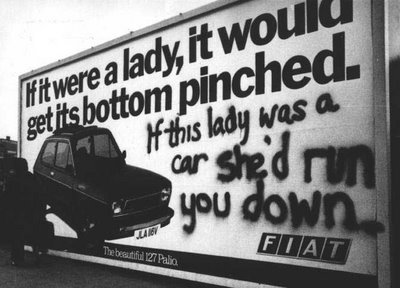

Image: A 'refaced' Fiat billboard from 1979

This type of paranoid moralistic thinking is baseless and damaging. ‘There has been a change in sexual behaviour, but it isn't as dramatic as the media make out,' said Dr Petra Boynton, a sex educator and academic:

Most young people still don't lose their virginity until they are over sixteen. If you take the generation who are now in their forties and fifties, many of them were having an awful lot of sex as young people, much of it unprotected sex. As adults we're very quick to look at young people and say, 'oh gosh, aren't they awful', but a lot of conversations that seem to care for young people actually end up being very moralistic about their behaviour, and start becoming discussions about what they should and should not wear, say and do.

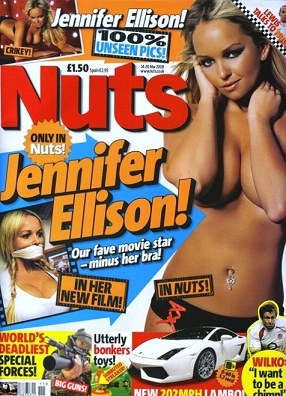

The single story told about the sexuality of young people, and of young women in particular, has them involved in a sort of abject whorishness that is as pernicious as it is pitiable. Adult society has begun to acknowledge that having to grow up in a hailstorm of media messages encouraging female erotic availability puts young people at a developmental disadvantage, but the same dialectic condemns the young as wanton strumpets - serial-shagging, binge-drinking and vomiting our worthless GCSES into storm drains with our knickers around our knees. Apparently unable to glance at the cover of Nuts without becoming pregnant, anorexic, or both, today's young women are imagined as special objects of pity and contempt.

Image: Cover of Nuts Magazine - home of topless girls, funny videos and fantasy football

There is, of course, a class element to this understanding of sexual victimhood. Hand-wringing tabloid articles about teenage pregnancy are invariably accompanied by model-posed photos of furiously smoking young women pushing prams around sink estates and scowling; in respectable magazines and political rhetoric, this translates to backhanded references to ‘girls from deprived areas'. ‘Sexualisation' is all well and good when middle-class parents order in crates of champagne for their teenagers' ‘sweet sixteen' parties, but utterly deplorable when hip-hop-listening working class kids attempt to Get Their Freak On. 'The perception is that it's only certain young girls who get pregnant,' explains Dr Boynton. 'It's the bad teenage girls who get dressed up in short skirts and hit the town. Class is often associated with the worst aspects of negative sexual stereotyping.'

The New Fun Police

This reanimated puritanism is thrown into ghoulish relief by an insistence on the absolute libertinism of modern culture, whereby any overt challenge to the erotic orthodoxy of the advertising and porn industries is seen as somehow ‘anti-fun': a wearisome distraction from the emerging utopia of liberated western hedonism. Scorn may be freely poured upon the wantonness of youth so long as our liberation from the punitive moral paradigms of the Victorian age is insistently celebrated.

The frigidity of mercantile eroticism is the ghost at this feast, which is why nearly every public conversation about sexual morality fails to distinguish between consumer culture's brutally identikit traffic in sexual signs and sex itself. The assumption behind the sententious moral message preached by the spokespeople of ‘family values' is that because we are surrounded by images of erotic capital, more actual sex, in the moist and panting sense, must be being had. This is in no way the case. What surrounds us is not sex itself but the illusion of sex, an airbrushed vision of enforced fun-fisting sexuality that is as sterile as it is relentless.

Image: One of the 'Flake Girls' from the Cadbury's commercials in the 1990s

Advertising surrounds us with what are supposed to be images of sensual pleasure: from adverts for Herbal Essences to the iconic, forty-year campaign for Cadbury's Flake bar, white women's faces are caught in what we have come to understand as a rictus of simulated bliss, their eyes elegantly closed, perpetually turning away as if in embarrassment at the orgasmic effects of product X. But something is wrong with the picture. One of the finest modern acts of counter-culture in its purest sense is the website Beautiful Agony, a group project wherein anonymous contributors submit short videos of their faces at the point of orgasm. Watching hairy Australian biker dudes and grungy middle-aged ladies snarling, chuffing and grimacing like chimps in heat, one realises the magnitude of the lie being perpetrated by mercantile eroticism. The collected videos, hundreds of which are submitted every month, have one thing in common: none of them would make you remotely more likely to buy a bar of cornershop chocolate.

In his essay The Finest Consumer Object, Jean Baudrillard assesses the first task of sexual counter-culture under late capitalism as being

to distinguish the erotic as a generalised dimension of exchange in our societies from sexuality properly so called. In the ‘eroticised' body, it is the social function of exchange which predominates. The erotic is never in desire but in signs. This is where all modern censors are misled (or are content to be misled) - the fact is that in advertising and fashion naked bodies refuse the status of flesh, of sex, of finality of desire, instrumentalising rather the fragmented parts of body in a gigantic process of sublimation, of denying the body its very evocation.

The ‘fragmented parts of the body' that Baudrillard describes are a key feature of advertorial eroticism: disembodied parts, particularly of women, are fetishised as symbols of a sexuality that they cannot access. Shampoo suds run down naked torsos in soft-focus; lingerie is stretched over moronically thrusting groins; and everywhere, on book-covers and cereal packets and boxes of sanitary towels, disembodied legs in stillettoed high heels emblematise a cutesy, feminine consumer imperative that edges to replace genuine erotic impulse in as sincere a manner as that in which O'Brien, in George Orwell's 1984, vowed that the party would destroy the orgasm. To borrow from Orwell again, one might well envision the future of Western sexuality in the form of a high heel stamping down on a human face, forever.

Learning Erotic Capital

The distinction that Baudrillard draws between erotic capital and sexuality itself must be understood as a real feature of contemporary sexual mores. Young people growing up with pressure to perform in every aspect of their lives find themselves aping a robotic capitalist eroticism that has little to do with their own legitimate desires.

I have a vivid memory of being impelled, as a grumpy fourteen-year-old, to take part in a musical competition with other girls in my school year in which we all performed a version of a popular music video in front of the rest of the school, in the name of ‘House Spirit'. My vote was for the Offspring's ‘No Feelings', but it was eventually decided that we would all dress up in ‘schoolgirl' outfits (as distinct from our actual uniforms) and attempt to recreate Britney Spears' ‘Baby, One More Time'. Those at a delicate stage of adolescence were provided with toilet-roll pneumatic breasts; we drew fake freckles on top of our real ones with biro and, when the day came, lip-synched along to the lyrics imploring a vague male cipher to perform unspecified acts of casual sexual violence. The crowd went wild. We hadn't been good; we hadn't even ballsed it up so concertedly badly that we deserved points for sheer shambolic brilliance. It was a whining, uncoordinated pageant of teenage sexual mimicry made worse by the presence of three perky stage-school girls blowing bubblegum at the front row and flashing their knickers. Like Britney, who at the time had yet to commit the transgression of finishing puberty, we were a bizarre drag act riffing on a plasticised version of adult sexuality. We got the biggest cheer of the evening. We were disqualified.

What our act expressed too vividly for the parent-judges to countenance was our innocent anxiety to involve ourselves in a culture of mandatory sexual performance. We had learnt from an early age that our bodily desires were the lesser part of our sexual development: far more important, for young people, is the creation and maintenance of erotic capital.

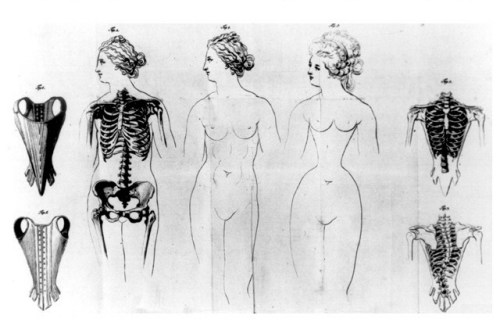

Image: Shaping beauty in the Victorian era

Adolescent sexuality, as understood and marketed by older generations, has become a ritualised act of erotic drag: a grim, unsmiling duty of knowing looks, coquettish pouting and occasional listless fucking to be undertaken by any young person wishing to advance themselves socially - or economically. Young people are not merely in the thrall of a culture of porn and advertising that seeks to sexualise us; we have always been more than simply a target market. What many of us understand quite profoundly is that sexual performance and self-objectification are forms of work: duties that must be undertaken and perfected if we are to advance ourselves.

Pornography is a part of this language of erotic duty, and any discussion of the ‘pornification' of contemporary youth culture must be understood in this context. The porn industry is worth some $14bn in America alone, and the explosion of online pornographic material freely available to young consumers provides a chorus for the consumer masquerade of paranoid, ritualised, repetitive heterosexuality. Feminist academic Nina Power explains that

The early origins of cinematographic pornography tell a very different story about the representation of sex [...] one that is filled less with pneumatic shaven bodies pummelling each other into submission than with sweetness, silliness and bodies that don't always function and purr like a well-oiled machine.

Power is right: when faces can be seen at all, nobody in contemporary pornography looks like they're having much fun.

The ubiquity of this blandly violent interpretation of pornography can be extremely bewildering for young people. Steeped in the shaming propaganda of our elders and bereft, for the most part, of any alternative educational or cultural models of sexuality, many of us begin our carnal adventures by attempting to reproduce the motifs of porn.

Young men, as well as young women, are intimately undermined by this grinding, relentless erotic model. I know at least one young man who, during his first sexual experience with a woman, was horrified to discover that he had not been expected to pull out and ejaculate on his partner's face. He had understood from watching pornography that the experience was what all women wanted.

Image: from a 1930s bondage catalogue

The formal rules of late capitalist pornography are the fulcrum of modern sexual affectlessness: an endless parade of disembodied cocks going into holes, a joyless, piston-pumping assembly line of industrial sexuality that seeks constantly to monetise new limits of ‘hardcore', to milk more cum, to stretch sphincters wider and open orifices to double, triple, quadruple loads of faceless genital meat. Naomi Wolf described in 1991 how pornographic signs had come to

people the sexual interior of men and women with violence, placing an elegantly abused iron maiden into the heart of everyone's darkness, and blasting the fertile ground of children's imaginations with visions so caustic as to render them sterile. For the time being, the myth is winning its campaign against our sexual individuality.

Much of the process by which the motifs of modern pornography have entered mainstream culture is excused by blithe claims on the part of producers and advertisers that this brutal objectification of young bodies is somehow ‘ironic'. The excuse is feeble; the irony, however, is real. The pastiche of sexuality adopted by ambitious young people is nothing if not ironic: how could we be at all self-aware and not comprehend the blackly comic alienation of erotic work?

Irony is, in fact, one of the few authentic motifs of western erotic culture in the early 21st century. A sort of kitsch, tongue-in-cheek naughtiness is relentlessly marketed at children and adults alike, from the peddling of ‘lolita'-themed bedspreads and schoolbags to the revival of ‘burlesque' which has been translated from its roots in working-class protest theatre to a tastefully bourgeois package of sexual objectification, wrapped in feather-fans and expensive corsetry.

As popstars and presenters clamour for their turn with the nipple tassels, businesswoman and burlesque superstar Dita Von Teese extemporises on what she calls ‘The Art of the Tease': 'I sell, in a word, magic. Burlesque is a world of illusion and dreams and of course, the striptease [...] As a burlesque performer, I entice my audience, bringing their minds closer and closer to sex and then - as a good temptress must - snatching it away.' The ‘tease' is a cry from the heart of the capitalist sexual manifesto. What is sold is precisely illusion: a campy, peek-a-boo frigidity that leaves the consumer dazzled and insatiate.

Image: New York Burlesque Festival

Apologists for burlesque as an art form tend to enthuse about the ‘empowering' nature of the ‘tease', which lost all of its underground credentials the moment bourgeois gyms started offering keep-fit burlesque classes. Polestars, one of the largest companies to run such classes in the UK, claims to ‘release your inner minx'. Sometimes one's inner minx just doesn't want to come out and play nicely. I lasted six months as a teenage burlesque dancer before all the saucy smiling started to make my face hurt.

Bunny and the Brand

The sudden ubiquity of the Playboy Bunny logo perfectly exemplifies this cutesey alienation of marketable erotic signs from the sweaty reality of sex. In the early 21stcentury, the Bunny began an inexorable hop into the mainstream, appearing on pencil cases, hairslides and other products marketed at children. Feminist campaigners were the first to respond, with worthy projects such as ‘Bin the Bunny' attempting to educate young girls about the harmful nature of the porn industry; next, the family values brigade hijacked the Bunny as a symbol of moral decline. British Conservative leader David Cameron spoke out against the rabbit in his election campaign of 2010, explaining that ‘when you see a little girl wearing a T-shirt with a Playboy bunny, that's wrong, isn't it?'

But the Playboy empire itself has long been in decline. In the half-century since Gloria Steinem went undercover as a House Bunny to expose the mawkishly misogynist vision of white, submissive heteronormativity peddled by the Playboy empire, Hefner has been far less successful as a pimp and pornographer than as a branding expert; even the revolving population of Playmates themselves are largely ignored by the popular press, the cotton-tail and flouncy ears looking droopy and dated in the harsh light of 21stcentury celebrity. When, in 2009, the Playboy empire went up for sale, buyers were more interested in the logo than in the rest of the crumbling, impotent company: ‘there is more to this brand than just sex', Kelly O'Keefe, a branding specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University, told Reuters. ‘There is sophistication, there is lifestyle, and there is freedom.'

Sophistication, lifestyle and freedom are worlds away from the fumbling, awkward, sticky revelations that necessarily accompany one's first decade of sexual experience. Fantasy is, of course, deeply implicated in the physicality of sex, which takes place at the panting border between dream and secretion, but the Playboy Bunny emblematises the absolute dislocation of fantasy from physical fact. The Bunny brand is a Lacanian play of signs bouncing blithely away from any signifiable sexuality.

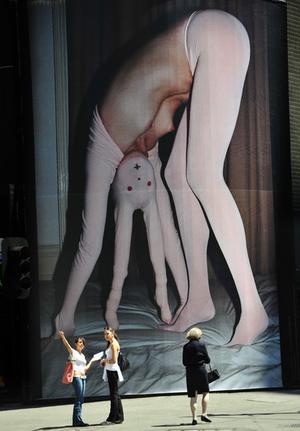

Image: Photo of Polly Borland's Untitled III installed on the Republic Tower, La Trobe Street, Melbourne by Jason South

It can hardly be argued that the ubiquity of the Playboy Bunny logo or its popularity with young girls are positive developments, but it must be understood that what is being objected to here, as elsewhere, is not sex, but symbol: the black-and-white, lipless, featureless symbol of a perky, prosthetic sexuality whose alienation from the flesh and intimacy of real sex can be mass-produced. At root, Bunny orthodoxy is repulsed by human personality, as Hefner himself explained:

Consider the kind of girl that we made popular: the Playmate of the Month. She is joyful, joking, never sophisticated [...] we are not interested in the mysterious, difficult woman.

The Bunny symbolises erotic capital as distinct from the lived experience of flesh. As a sign, it overwhelms the sexual encounters it has come to signify. A 2010 survey of unmarried Americans between 18 and 29 revealed that many have little knowledge of even common contraceptive methods such as condoms and the pill, but when we first saw the Bunny on our lunchboxes, we had a naughtily amorphous understanding of what it was supposed to mean. And one thing is certain: when a fifty-year-old rubber-stamp rabbit in a bow-tie becomes an internationally recognised sign for the mummy-and-daddy dance, it's safe to say that something has gone horribly wrong with our understanding of sexuality.

Starving Hearts

What is at play here is a horror of flesh: a rubberised capitalist repugnance for flesh and the intimacy of human sexuality. Modern censors are necessarily misled about the nature of consumer frigidity, because their complicity is a necessary part of the trick: the strategic alienation of sexual consumers from their erotic selves relies precisely on censorship to blur the distinction between sexual intimacy and erotic capital, only one of which can be mass-produced. Such a joyless vision of eroticism only looks edgy and exciting because young people have nothing else to work with. A new model of corporate puritanism is on the march, and what is being censored on all sides is precisely Baudrillard's ‘evocation of the body'. This emotional censorship is deeply traumatic.

Eating disorders such as anorexia and bulima are a private, violent expression of this cultural trauma, wherein young women are commanded to always look available but never actually be so. If the bodies of the young are there to be socially and sexually consumed, our most drastic retaliation to this duty is to consume ourselves - and so we do, in ever-increasing numbers. Since 1999, there has been an 80 percent rise in the number of teenagers admitted to hospital with anorexia nervosa; across Europe and America, one in every hundred young women and one in every thousand young men has the disease.ii Roughly double those numbers suffer from bulimia nervosa or other pathologically disordered eating patterns. One in ten young sufferers will die from the direct effects of the disease, and over half will never recover, living with years of complications and, in many cases, choosing to take their own lives. Naomi Wolf was the first to identify the link between eating disorders and the duty of perfection in social and erotic display.

Image: Juicy Couture advertising campaign

In 1991, Wolf described in The Beauty Myth how the epidemic of eating disorders amongst young women in the West had been ignored by world media and governments, rightly identifying the omission as evidence of the sexist priorities of healthcare and social strategists across the world. This is no longer the case. Two decades on, the same culture is saturated with films, books, documentaries, plays and endless harrowing newspaper articles all claiming to ‘expose' eating disorders - chiefly anorexia nervosa, the more glamorous and alien sister in the murderous family of self-denial disorders. Open any magazine, click on any gossip website, and you'll find speculations on the latest celebrity's suspected bulimia running alongside columns on what Madonna doesn't have for breakfast these days. The media has turned anorexia and bulimia into the diseases of the moment - gruesome and disgustingly cool, evidence of the supposed fragility and incompetence of successful women in the public eye.

Concern for the mental and physical health of the youth of tomorrow is clearly not the priority here. In fact, recent attempts by the international media to ‘raise awareness of the dangers' of eating disorders have looked less like a genuine campaign than a series of mad, gory collisions between a famine relief documentary and a porn movie. In the promotional posters for the 2008 ITV documentary ‘Living With Size Zero', a model with rake-thin limbs stands with one leg cocked on a set of scales, wearing nothing but skimpy underwear and pouting provocatively at the camera, aping a sexual attraction her emaciated body is chemically unable to produce. A tape measure is wound tightly around her torso. Her face is made up and filled out with clever airbrushing; her hair is perfect. This is not ‘raising awareness' - this is idolatry.

This hagiography of the anorexic points to something very pressing about modern society's horror of needy, hungry human flesh. Not so many decades ago, the easy link between sexual desire and hunger for food was a wellspring of cultural play: today, consumer logic imposes an artificial and insatiable appetite for bland food and boring sex whilst punishing us for actually indulging in either. What eating disorders appear to offer is salvation from this paradox of contemporary desire.

Schooled by the circumspective propaganda of the fashion, diet, beauty, music, media and pornographic industries, my generation has a learned tendency to despise its own flesh. The discrepancy between the dogged models of erotic and social self-fashioning offered to us and the reality of our everyday lives and developing bodies can be almost unbearable. Celebrities and fashion models who are tacitly understood to be engaged in a prolonged process of self-starvation, seem to promise to teach us both how to be desired and how to disengage from our bodily desires. It is easy to ache for the perfect control they seem to embody, to yearn to be the ubiquitous object rather than an abject consumer. It is easier to learn not to want anything: easier to play the rules to their ultimate, tragic conclusion and refuse to consume anything, to punish the body and murder the sex drive with the artificial pre-pubescence chemically created by starvation. Easier to become a sign rather than attempt to signify anything. Easier, ultimately, to die.

Freeing The Flesh

Antiquated paradigms of sexual morality policed the sexuality of young people with a variety of instruments of rusty erotic torture, from tight-laced steel corsets to spiked genital casings designed to prevent young men from masturbating. Our liberated, libertine age of funtime mercantile eroticism requires us to internalise the corset and the spikes; to starve, suffer, spend, primp and perform, to take our place in a monetised pageant of sexual scarcity when, in fact, we have always lived in an age of erotic abundance.

The ooze and tickle of real-time sex, which can neither be controlled nor mass-produced and sold back to us, threatens both capital and censorship. Shaming the choices of young people whilst bombarding us with pounding, plasticised, pornified visions of alienated sexuality creates an impression of sexual scarcity that serves both agendas. But if human beings own anything by right and birth, we own an abundance of flesh, an abundance of dirt and sex and sublimity. Only by embracing this abundance can we liberate ourselves.

Image: Between women

The eroto-capitalist horror of human flesh, and of female flesh in particular, is a pathology that can and must be resisted. If we are to free ourselves from this pernicious fear of flesh, we have to learn to live in our own bodies. We have to reject the narrow coffin of performance and perfection laid out for young women and increasing numbers of young men, and learn to evoke and respond to our own desires.

If we are ever to achieve real sexual freedom, we must be brave enough to resist the ruthless logic of performative erotic irony, and brave enough, above all, to be anti-fun. If ‘fun' obliges us to self-objectify, to strip down our flesh and sterilise our desires in the name of edgy empowerment, then we should reject it. If fun bribes us to smile and smile whilst the best and lustiest desires of our young hearts and groins are stolen, mass-produced and sold back to us, then we should discard it. If mercantile sexuality cannot be touched or kissed, if fun is no more than ironic, asinine erotic capital - then we can do better than fun, and we can do better than fear.

Laurie Penny <laurie.penny AT googlemail.com> is a 23-year old journalist, writer and feminist activist from London. Her blog, Penny Red (http://pennyred.blogspot.com) was shortlisted for the Orwell prize in 2010. She is Features Assistant at Morning Star and writes for New Statesman, Prospect and The Guardian

i See for example http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/facebook/7508945/Facebook-linked-to-rise-in-syphilis.html

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com