The Failure of Political Theology

The notion of the 'failed state' is recurrently invoked to justify military and security interventions. Reviewing two books which take so-called failed states in Africa and South America as their object of enquiry, Angela Mitropoulos questions the founding premises of 'successful' national sovereignty

Regimes of ‘parcellized sovereignty’ and ‘fragmented peace’ led to an international humanitarian crisis that overran national borders and threatened the sovereignty of neighbouring states.

– Forrest Hylton, Evil Hour in Colombia, London: Verso, 2006

By firmly rejecting any notion of the relativity of truth, monotheism postulates the existence of a universe with a single meaning. In such a universe, the space left for dissent is, in theory, very small. Imaginable conflicts cannot concern either the ultimate meaning or the ways in which this meaning is constituted, since, like this meaning, the modalities of its constitution belong to a system of truths assumed unchangeable

– Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001

The concept of ‘failed states’ is ubiquitous in political idiom and theory, extending well beyond its methodical appearances in recent global security vernaculars. Unlike the fable of the Weapons of Mass Destruction, it rests on a political mythology that is all the more robust to the extent that, as with all theologies, it cannot be falsified. Codified in the US Government's National Security Strategy of 2002, state failure has been tendered as the significant clause in the doctrine of pre-emption. That document famously announced that 'America is now threatened less by conquering states than by failing ones.' It has, moreover, become the principle behind Australian judicial and paramilitary interventions into, most notably, the Solomon Islands – and more besides. There are two broad versions of 'failed states', one more or less Machiavellian in its preoccupation with risk assessment and the grasping of opportunities through force; the other more or less theological (or Hegelian) in its denials of the violence that founds and sustains the state, such denials are underwritten by the premise that the state is the inevitable and universal form of politics, relation, and sociality. Where one version defines a failed state as a situation in which 'the central government loses the monopoly of the means of violence', as does Michael Ignatieff, the second characterises state failure as the inability of states to protect the health and lives of their citizenry.[1] But while the first, as the oftentimes explicit outpouring of geopolitical and military deliberations, is an easy target for radical criticism, the second – in obscuring the question of this monopolisation of force and, thereby, construing the state as the advent of the social contract which magically puts an end to violence – imagines an ideal (or radically different) future can be built upon the dialectically perfected assumptions of the first. Not least, the question of whether states ever in fact do ensure the safety of all of their citizens or, more sharply, why citizenship forms the limits of care is never posed.

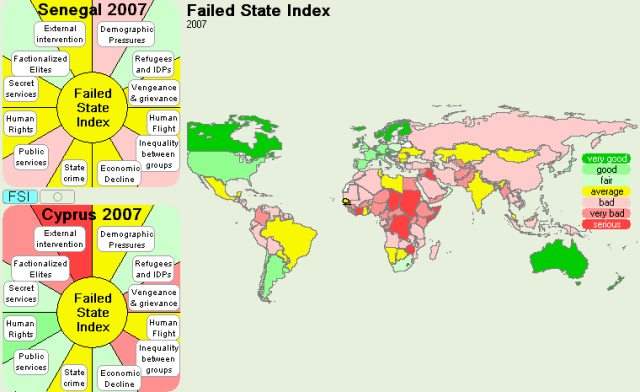

Image: Map of failed states from www.foreignpolicy.com

Indeed, it might be noted that the very idea of a failed state presupposes criteria of success, boundaries and a teleology that are matters of long standing faith in parts of the Left and so-called NGOs, just as they have been in Washington. Moreover, one of the most prominent hallmarks of state failure, it is said, is the inability to control the movements of people across its borders. Thus, combining the norm of state boundaries with an evolutionary credo, the discourse of failed states, particularly in its Hegelian registers, is a revised version of modernisation theories, of a sense that the world moves inexorably and totally along a certain and linear trajectory. And, to the extent that this trajectory is considered inevitable, as a matter of belief if not existence, explanations for its non-actualisation are almost invariably situated in factors deemed external, as interruptions by a putative outside, by what is foreign. That is to say: nothing to do with 'us'. In this way, it is not, as it were, the theory of modernisation which ever hazards failure. On the contrary, the political theology of democracy self-immunises by arranging itself as the one truth of the world – anything else is deviation. Failure is located not in the theory of the state, or in democracy, which in any case is regarded as an ontological given, but in that which has, according to this view, refused, obstructed, is recalcitrant, or weak. The dynamic of this view is as apparent in the US Democrats' presentation of arguments for an 'exit strategy' from the catastrophe in Iraq – increasingly depicted as a result of the deficiencies of 'Iraqi leadership', a civil (but not global) war, etc – as it has been in recent paramilitary interventions in indigenous townships in Australia.[2]

Image: Failed States Index, http://esl.jrc.it/dc/fsi_2007/

Therefore, what the revision of modernisation theories marks is that what was always crucial to such understandings is not the posited end-point; that is, not the dream of a world neatly partitioned by democracies giving eternal and harmonic expression to non-violently competing interests. To be sure, this imaginary terminus of a world operating as smoothly self-calibrating (political) marketplace is significant. It serves to morally but not factually differentiate the violence of democracies, and that which occurs in democracies, from that of despotic regimes by dint of the former's never-attained telos of an infinite and universal peace. Nevertheless, what is at stake here remains the question of an originary or foundational violence that in important respects is not constrained to an originary or foundational temporality. Neither is this violence in the past nor does it return anachronistically, even as its appearance in the present serves as the legitimation of force passing itself off as the dream of the creation of an eternally non-violent space. Which is to say, such violence is coincident and persistent, oscillating between supposedly exteriorised and internalised expressions or – if one grants certain assumptions their rhetoric – extortion and taxation, the segmentations of warlordism and coherent territorial sovereignty, and so on. Of course, some time ago, and running against such assumptions, Charles Tilly suggested that if 'protection rackets represent organised crime at its smoothest, then war risking and state making – quintessential protection rackets with the advantage of legitimacy – qualify as our largest examples of organised crime'.[3]

In any case, between these two poles of the ostensibly legitimate and the literally outlaw, political thought has long had recourse to the transitional figure of the Prince. In his Hegelian reading of Machiavelli, Gramsci began by insisting that the Prince – which is to say, the aspirant to sovereignty – is a kind of Sorelian myth. This figure is, he argued, 'a creation of concrete fantasy which works on a pulverised people in order to arouse and organise their collective will'. In other words, and as Gramsci accepts it, a people might well be 'pulverised'; however it is the very sense of a disintegration which not only presupposes a given foundational figure of – though also beyond or prior to – politics, but impels the constitution of sovereignty forward. That Gramsci proceeds to write of the division of labour in Marxian terms does not interrupt this teleological couplet of eventual/pre-existing unity and his embrace of it. In other words, and despite the marxian jargon, class does not, for Gramsci, irretrievably split the (Italian) people. It does not call into question the ties that might bind class to nation – they are simply there, perceived as a problem only to the extent that they are posited as unravelled. Therefore, insofar as sovereignty is presented as fractured merely impels a greater effort toward its re-composition or re-unification. And so, as is more or less well-known, Gramsci preoccupied himself with various schema which seek to explain and overcome this purported condition of disintegration. This is the question which informs almost all his writings and significant concepts: on the 'southern question', 'passive revolution', 'hegemony', his definition of the party as the Modern Prince, and so on. Gramsci, then, combines Machiavelli with Hegel and arrives at a variant of social contract theory with Marxian pretensions.

Image: Camp Justice, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba

With those preliminary remarks, let me turn to two books that offer somewhat divergent accounts of these doctrines and histories that swirl around the concept of failed states: Forrest Hylton's Evil Hour in Colombia and, less recently published, Achille Mbembe's On the Postcolony. Situated according to specific geopolitical and geophilosophical conjunctures, Evil Hour in Colombia might be read as a repudiation of US fears of the rise of radical populisms in Latin America; On the Postcolony as an intervention into the sense of Africa as, to put it bluntly, the absence of Europe. But if the first, in its rigorous detail of the history and phases of Colombian politics, appears as more accessible and hence explicitly political, Mbembe's book – as it turns around themes from the privatisation of war to God's phallus, and in idioms as diverse – challenges many of the assumptions that produce what is intelligible in and as politics. Both books raise the question of whether it possible to write about and, importantly, beyond the theoretical construct of weak states and strong states – or of failed and successful ones, of transitions to democracy and military adventures undertaken in pursuance of democracy – without recapitulating its forms of address, intonation, figures and aims and, ultimately, its affective pull. This construct is the quintessential theological manoeuvre of democracy. It is the secularised version of a theological temporality which insists that 'contradictions' will work themselves out 'in time' or, put differently, that the 'democratic deficit' will be converted into a surplus, even while it abundantly clear that such 'contradictions' (or 'dysfunctions', 'deficits' and exceptions) are already arranged through the ongoing demarcations of space, not least in the very borders that constitute Colombia, Africa, and Europe, or the banlieues and camps, evictions and dislocations, deportations and migratory flows. And, it is surely a matter of making explicit those assumptions which become so familiar they grant an accessibility, to a reader who is assumed to be exemplary of readers everywhere, and which bear down with a weight that can no longer be recalled because it has never seemed otherwise. To put this another way: the theories which shape Evil Hour in Columbia, which arrange its questions and structure its search for answers, tend to appear as self-evident. Without posing any questions about its distinctively Gramscian theoretical framework or even making it overt, all that seems to remain is a sorting of data into a model whose truthfulness is assumed: the periodisation of history, the assortment of pertinent actors into (or, more accurately, as) subalterns, ruling class fractions, parties, etc. There is, for instance, little discussion of union organising, even though this is subject to some of the most persistent violence and repression in Colombia, because this is not the narrative Hylton chooses to relate. For Hylton, as with Gramsci, the (Colombian) people are pulverised – but this figure of the people, of the popular, seemingly arises out of nothing, causa sui like God, only to be, at some particular point, deprived of its comprehensive actualisation, representation, or inclusion. But to read Hylton's book alongside On the Postcolony is not only to wonder at Hylton's acceptance of the fundamental questions from which the hypothesis of failed states is derived; it is to bring the colonial, monotheistic and masculinised specificity of these questions to the fore.

Where Mbembe begins On the Postcolony with the insight that Africa has, more often than not, been regarded as a space exemplary of an absence, Hylton's book responds to the propositions of a lack – in this case, insofar as it serves as the pretext for US intervention in Colombia – with the argument that it was precisely this kind of intervention that brought about this deficit of sovereignty. And he carefully sets about situating those moments when the accomplishment of Colombian plenitude was frustrated, cut short as it were in the liquidation of the 'broad Left'. To be sure, Colombia, much like Africa, has long been associated with the 'fragmentation of sovereignty'. But that the violence in Colombia or Africa is explained as an outcome of the dispersal of sovereignty means that one has already accepted the premise, on faith, that the realisation of sovereignty will entail a cessation or diminution of violence – not to mention giving credence to the once-upon-a-time of sovereign coherence. For Hylton, the question of violence – attenuated to the insurgencies and the 'shadow state' in Colombia – is a consequence of the 'exclusion of popular ... demands from the mainstream political system.' There is no prospect of posing the question here of whether, in light of an exclusion which has been more or less systematic, the very identity of Colombia, or the Colombian people, might be called into question – or, for that matter, whether this identity is possible to constitute and sustain without violence. Nor is there space for the suggestion that inclusion might not be all it virtuously promises, particularly given Hylton's acknowledgement that inclusion has, concretely, taken the forms of patronage or, more recently, integration into 'democratic security' systems; that is, not a lessening of violence or of poverty, but the modulation of their patterning which will remain contingent and revocable.

It is not at all clear, for instance, that the recent demands for 'autonomy' and 'independence' by the 7th Inter-Ethnic Solidarity Conference (composed of the descendants of African slaves and indigenous groups) can be entirely – or more fruitfully – understood in terms of democratic politics, whether liberal or populist. Might there not be, here, the possibility of another form of politics, one that is not caught up in the incessant dynamic of both distinguishing and fastening 'el pueblo' to 'the elites', or exhausting the sense of politics in this nationalist dynamic? For while Hylton does indeed juxtapose the politics of the 'elites' to that of, say, indigenous groups, and their varying definitions of democracy, equality and so on, insofar as the scope of his analysis does not shift outside the borders of Colombia, whatever differences and tensions there are risk remaining thought as the oscillation between these two figures (or 'poles') bound within a national framework, albeit one that is perceived as fragmented, but nevertheless mutually constitutive. In short, an idealised version of the nation-state implicitly accompanies Hylton's otherwise rigorous account. In Evil Hour in Colombia, the people (unlike the elites) are politically and economically marginalised while symbolically central to the nation. And, while Hylton's book is to be lauded for its regard for the politics of indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups, it is this contradictory presentation of the people – actually marginal while symbolically central – that threatens to bind futurity, strategy, authenticity and antagonism to the nation-state and its contours, thus inclining the analysis to repeating the impasse of those other aspirants to state power in Colombia, such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia.

If the 'elites' of Colombia are invariably presented as an extension of US economic and military power, then why do the indigenous peoples and descendants of slaves only appear within the confines of Colombia's borders? Is there no communication, interaction or movement across those borders that is not made suspect by an association with imperial power? I assume there is, but there is little discussion of it in Evil Hour in Colombia. And while such omissions can serve to leverage the presentation of a populist democratic authenticity, they also implicitly rest on the conflation of 'foreign' with 'elite'. In other words, it is not I think sufficient to admit criticisms of the armed insurgencies and, conversely, a regard for indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups if the same political logic of (or wish for) representation is simply transferred from the former to the latter. Nationalist logic does not unfold without violence, even if some of its aspects may not, at present, be armed. And so, while this may remain a theoretical point, the purported discovery of a potentially radical (or revolutionary) subjectivity in 'third world' subalternity should raise the question of exoticism and its consumption. Indeed, this question should already be an explicit one in the wake of the mutation of third world nationalisms into bantustans, or worse. More specifically, it poses the question of what happens when such consumption is disappointed – which is to say, the transformation of exoticism into overt racism, as 'third world' subjects fail to deliver on the European teleology they have been imbued with.

In any case, for Mbembe, on the other hand, the question of violence and that of specifically colonial forms of sovereignty cannot be detached. There was no mythical past in which sovereignty – or a people – existed only to be sundered; nor is there a paradisaical future in which sovereignty can be separated from questions of continuing forms of violence, however redefined or re-organised. Colonial sovereignty, he argues, rests on three forms of violence: founding violence, that creates the space over which sovereignty operates and through which it tautologically presupposes ‘its own existence’; legitimating violence that produces ‘an imaginary capacity converting the founding violence into authoring authority’; and the violence of maintenance, that while falling ‘well short of what is properly called ‘war’, it recurred again and again ... played so important a role in everyday life that it ended up constituting the central cultural imaginary that the state shared with society.’ Sovereignty, then, does not constitute peace, but the circumstance for the co-presence of order and stability alongside arbitrariness and impunity.

Image: Evil Hour in Colombia, book cover

The broader question that arises, therefore, is how this co-presence of order and arbitrariness – or, perpetual peace and permanent war – is distributed and thought. For classical European political theory, and according to its dramaturgy of the political, the latter was construed as the inherent condition of the non- or pre-European. European political space, by contrast, was posited as normatively contractual and, for that matter, the norm. Yet, as Hylton's book does make clear, Colombia is characterised both by a long-standing, bi-polar democratic polity and wars conducted along the complex axes of the narcopolitical, paramilitary and insurgent. In other words, the distinction between zones of peace and zones of war does not neatly match with the differentiations established by borders, even if this is what borders have, in theory, purported to realise. Moreover, this situation in which the legitimate and coercive – or peace and war – are, as Mbembe will put it, entangled is the condition across the African continent.

One might add, however, that this entanglement is also the circumstance of the world – contrary to European normative views of the border that are, I would contend, increasingly as inapplicable to Europe as they are to elsewhere. I will come back to this, but let me note here that the geopolitical distribution of the ostensibly contractual peace and the seemingly permanent war without end that much political theory rests upon is not entirely fictive, even if its actual historical appearance is, I would insist, more brief and exceptional than supposed in that theory, and even while that distinction has been, more often than not, reliant on habituations that remains, at its edges, secured by applications of violence. Nevertheless, colonial spaces did indeed take on the characteristics of the 'state of nature' or of permanent war – but, against Social Contract theory, they did so in that colonial encounter; just as metropolitan regions and markets acquired the demeanour of socially contractual space through the formal and corollary determination of types and regions of labouring that were anything but contractual or paid. That is, the organisation of bordered zones and frontier spaces does involve the distribution of violence and its forms which are in no way commensurate. This, however, is not to suggest that conditions remain the same, that border and frontier are as distinctly located as they were during Cold War and Bretton Woods disbursements, that postcolonial and metropolitan forms of governance are as spatially demarcated as one might think.

Image: Nick Hannes, Centre 127, a state-run detention facility located within the Brussels airport premises in Melsbroek

Image: Nick Hannes, Centre 127, a state-run detention facility located within the Brussels airport premises in Melsbroek

In the chapter 'On Private Indirect Government', Mbembe charts what he describes as the emergence of 'multiple forms of private indirect government' that have attended a simultaneous formal de-linking and informal integration of Africa from, and in, global economic arrangements. Against the background of the political forms of the slave economy and Structural Adjustment, he notes the rise in 'a new form of organising power resting on control of the principal means of coercion' in territories that 'are no longer fully states.' He goes on to note that, in these cases

borders are poorly defined or, at any event, change in accordance with the vicissitudes of military activity, yet the exercise of the right to raise taxes, seize provisions, tributes, tolls, rents, tailles, tithes and exactions make it possible to finance bands of fighters, a semblance of a civil apparatus, and an apparatus of coercion while participating in the formal and informal networks of inter-state movements of currencies and wealth (such as ivory, diamonds, timber and ore). ... the process of privatizing sovereignty has been combined with war and has rested on a novel interlocking between the interests of international middlemen, businessmen, and dealers, and those of local plutocrats.

Image: Refugee camp in western Sahara, http://www.arso.org/05-3.htm

This is strikingly similar to the conditions in parts of Colombia Hylton describes. But whereas Hylton maps similar changes in the rise of Colombian parastate organisations, the informal economy and so on, unlike Hylton, Mbembe does not grant any implicit normative credence to the distinction between warlordism and statehood. Rather, On the Postcolony is concerned to analyse such forms of power and exploitation as they arise in their complexities, and not index them according to geopolitical theories whose processes of development and truth are assumed.

But if Mbembe complicates the relation between border and frontier without recourse to European imaginaries of the political, in noting the poor definition of borders in some cases – as well as, elsewhere, the predominance of casual labour – On the Postcolony raises the question of whether these might indeed be considered as properly postcolonial experiences. Without for a moment suggesting that metropolis and postcolony are indistinguishable, it should be noted that the privatisation of war-making (eg, mercenaries and Green Card soldiers), as well as public space and its securitisation, not to mention casualisation and the extraterritorialisation of borders, are also notable aspects of transformations in the administration of violence and exploitation conducted in and by metropolitan states. I've argued elsewhere that such changes emerge in the wake of global migratory reversal of the post-WWII period, and won't reiterate that argument here, except to note two significant implications. First, colonial forms of control are no longer confined to (post)colonial spaces, and it is arguable whether they always were; and secondly, this points not to the power of metropolitan states, but in every case to their 'weakness'. Resorts to just-in-time border technologies, urban lockdowns, the privatisation of war, the proliferation of internment camps, and so forth may well indicate circumstances both horrific and unbearable, but insofar as they signal innovations in techniques of control and exploitation, they also indicate the failure of prior technologies to accomplish their task.

If I might, then, conclude with a criticism of both books, it is that neither quite grasps the possibility inherent in this moment. Evil Hour in Colombia, in its adherence to Gramscian precepts, might well seek out the possibilities of struggle and subaltern agency against oppression, but it can only recognise struggle as a recapitulation of categories which remain trapped in nationalism, albeit of a postcolonial – or, more accurately, third worldist – variety. On the Postcolony, in its refusal to concede the normative quality of a European ontology, might well bring a refreshing set of concepts and analyses to a complex landscape, but oftentimes reduces that landscape to forms of control, exploitation and the constraint or releasing of populations according to the logics of the former. But if there seems to be here a dispute between the analytics of Gramsci and Foucault, or between analyses of subjectivity and those of subjectivation, this may suggest that the pertinent political question is no longer resident in either 'camp'. If Evil Hour in Colombia achieves a kind of marxian legibility by substituting the figure of el pueblo for class, On the Postcolony challenges the reader to ask some difficult questions about the (post)colonial circumstances in which familiar political figurations are formed and dispersed, composed and recomposed in new ways, and perhaps in ways that are not recognisable to political theory at all, only to henceforth and interminably be marked as lacking, failing or, as Mbembe remarks on Africa, 'a mute place of darkness, amounting to no more than a lacuna.' The question of politics, then, may not be either how to discern the traces of a (prospective) revolutionary subject (Hylton's implict question) nor how to shake off the racialised denials of subjectivity insofar as they do not adjust themselves to a European sense of the political (Mbembe). Perhaps the question of politics, today – given the entanglements, shifting borders and 'colonialisation' of metropolitan spaces alluded to above – can only be posed as a question of the postcolonial. Though, to be sure, that question cannot begin to be put without passing through both On the Postcolony and Evil Hour in Colombia.

Angela Mitropoulos <s0metim3s AT optusnet.com.au> lives in London

Footnotes

[1] Michael Ignatieff, 'Intervention and State Failure', Dissent, 2002.

[2] For more on the latter, see my forthcoming essays (2007) in the Sarai Reader and darkmatter, http://www.darkmatter101.org/site/

[3] Charles Tilly, 'War Making and State Making as Organized Crime' in Bringing the State Back, Evans et al, (eds), 1985.

Info

Forrest Hylton, Evil Hour in Colombia, London: Verso, 2006

Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com