Dealing With Eco-Data

In response to Cooper James’s article about the media’s wilful ignorance of the ecological crisis (Five Years, Mute # 12), Noortje Marres takes a closer look at the nature of the ecological data circulating in the media. Should we sanctify them and preach the scientific fact of fast approaching global catastrophe? Or should we realise that eco-data point at problems that are much more open-ended: that it is not the fact of ensuing disaster that should be propagated, but the change of lifestyle that eco-data demand. The importance of such a shift in emphasis becomes obvious when we look at the use governments and corporations make of eco-data.

The amount of ecological data circulating this planet is mind-blowing. Massive quantities of air time and print space are being dedicated to nature, or what used to be nature, in scientific publications, magazine cover-stories, policy proposals and TV news. Eco-data blow our minds because of the decay and disaster they speak of. Eco-data present us with innumerable anecdotes and scenarios, ranging from the mildly disturbing to the highly alarming.

But it is important to realise that however threatening the message, global ecological catastrophe is not a certain fact. Firstly because eco-data often locate catastrophe in the future: “A wave of humanity 300 feet tall and 3 billion people deep will wash over the world’s cities within the next 30 years.” States of emergency are proclaimed now for the sake of a probable but unforeseeable future. But also because, when eco-data are used to humbly describe a present situation, they rarely come in the form of a classical statement of fact. The environment-related sciences work increasingly with estimates of probability, deriving distributions of chance from models and simulations. While these calculations almost always have certain spot checks as their input, their results give insight into hypothetical worlds, not into some straightforward reality: “Toxic algal blooms may cause lingering damage to public health.” Another reason why we should not expect full-scale certainty from eco-data is that they are data. Raw data come from all over the place (earth observation satellites, Geiger Müller tellers, toxicity tests, pedocomparators, weather balloons) and travel all over (from raw data, to scientific publication, to magazine cover-story, to policy proposal, to TV news). Eco-data pass through an infinite series of translations. They are always already manipulated.

Events to come, probable worlds, endless editing and adaption. Eco-data provide specific views on potentialities. Seen in this light, it becomes clear why governments and corporations have become so good, so fast in adjusting their practices to the bad news of the ecological crisis. Instead of commanding an immediate ban on the production of all toxins, an absolute end to the felling of trees, eco-data allow for a wide variety of formulations of a wide variety of ‘effective responses’ (the same goes for the problem itself – a British government official managed to boil the entire ecological crisis down to: “it’s a matter of the right molecules in the wrong place. There’s nothing like pollution, it’s all molecules.”). Nevertheless, eco-data confront governments and corporations with something unusual. Governments used to rely on science as a provider of uncontestable facts which were useful for justifying policy. But as the environmental sciences tend to come up with nothing more than tentative hypotheses, policy cannot be presented as a natural and thus legitimate outcome of the facts delivered by science. Corporations have long found ways to manage trouble coming from beyond the boardroom, such as workers’ demands or government regulations. But the problem of waste and product-ingredients unexpectedly getting back at them in the shape of evidence for eco-offences is a hard one. Virtually every stage of the production process runs the risk of being subjected to eco-analysis by experts from the outside. Not knowing exactly where data might emerge from, it is difficult to prepare a defense. So, how do governmental and corporate players tame these nasty features of eco-data?

Can’t Stand the Heat? Change the Climate!

Obviously, eco-data first have to be produced before they can begin to enter organisations. In the case of genetically modified food, there is a huge lack of publicly available data. The approval of GM foods by the U.S. government has supposedly been made on the basis of one scientific article about a modified tomato. In the UK, it has led to an exceptionally successful attack by NGOs and an embarrassingly weak defense by politicians and corporations. In the absence of evidence, be it pro or con, reassuring voices sound like sales pitches, and mobilised public conviction overrules them, at least in the public realm. It is rare for this level of public disapproval to precede data collection; most of the public eco-debates in the nineties have only got going after research was underway and governments had enough information at their disposal to take a founded position. The debate on global climate change for example, might even be said to have been propelled by European governments. Under the banner of the United Nations, a global collaboration between scientific institutes (IPCC), a series of global summits (Rio ‘92, Kyoto ‘97, Buenos Aires ‘98) and other sorts of global policy makers’ get-togethers (UNFCCC), have been set up. By now most of the oil and car companies involved have developed some sort of climate policy. Eco-data is circulating in top gear.

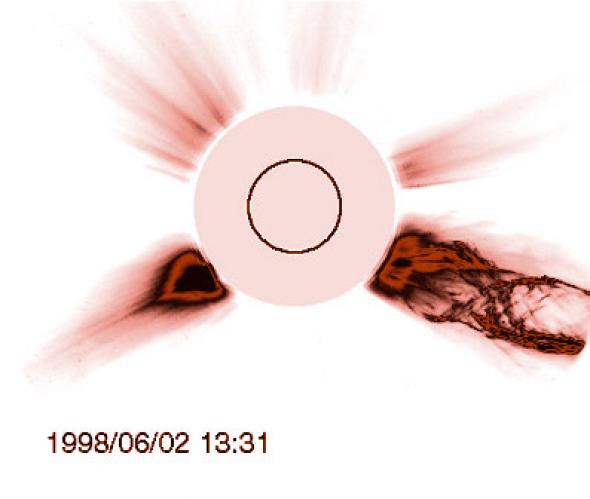

>>Images: March Global Temperature and Precipitation Anomalies from National Climatic Center / NESDIS / NOAA

Among the many reasons why European governments initiated this huge UN climate campaign, is the fact that the climate problem has the potential to bring forth one big solution to an ocean of eco-complications. As climate change seems to be caused by one of the most basic products of human industry, the emission of CO2, it penetrates the core of the ecological crisis, a core that hands-on responses to end-of-the-pipe calamities (oil spills and waste disposal) cannot reach. Secondly, being a global problem, climate change allows for a removal of eco-policy from the hotbeds of ‘pollution events’, which often get messy and emotionally laden because of the civil parties involved attempting to force Western governments into immediate and drastic action. At the UN level, politicians and policy-makers can work on eco-problems at their own pace. Thus an enormous climate data processing institute (IPCC) was set up to coordinate the collection and sorting out of meteorological and geophysical information from all over the world. The centralisation of data-gathering and processing would result in an overview of the Earth climate system, which would allow policy-makers to make clean and generally acceptable decisions.

Of course it didn’t work out that way. The reports delivered by the IPCC were full of tentative statements, partly contradictory and partly mutually supportive. And consequently, the politicians and policy makers of the UNFCCC soon found themselves having the same debates the scientists were having down the corridor: do these models take the relevant factors into account, what do these observations point to? The political debate started to polarise according to the different scientific views on climate change (and vice versa): those against subjecting industry to a CO2 emission reduction program saw climate change as a purely natural and harmless phenomenon and those who were for it presented climate change as the next great human threat to humanity after the atom bomb. Still, the UN continued to work according to the classic division of labour between science and politics – science provides unbiased facts, and after that government decides on policy. So long as there is uncertainty there can be no decision. When it finally dawned on them that it is not very reasonable to expect unanimous scientific certainty about the present and future state of the entire earth, nor to postpone decisions until that moment (a climate scientist parodied the absurdity in this way: “if we act now, we will never know whether we were right.”), they decided to at least emulate scientific certainty. In Kyoto, December ‘97, government delegates signed an agreement that contained both a fact and a policy commitment: “the balance of evidence suggests a discernable human influence on global climate” and “the industrialised nations will reduce their CO2 emissions by an average of 5 percent (compared with 1990 levels) by 2012”. Beautiful. Or so it seemed. During the next summit (Buenos Aires, November ‘98), which was supposed to yield concrete policy proposals (how to steer industry and car users towards reducing their CO2 emissions), the negotiations reached a deadlock. The unified politico-scientific position that was manufactured at Kyoto turned out to be too far removed from the ‘pollution events’ on which it was supposed to have an effect. Its language turned out to be too global for it to compel the representatives of industry to commit to any practical change of lifestyle (a different style of production). The next summit is scheduled for 2000.

How Risk Inc. Came in Handy

How did corporations respond to the upsurge of climate data that came into circulation once the UN had set its climate campaign into motion? At first, the information that man-made CO2 emissions, that is to say the burning of fossil fuels, which is to say the oil and car industries, are responsible for climate change, was simply debunked by the oil and car companies. Before the Kyoto agreement, when there was still significant support among government delegates for the no-scientific-proof-means-no-action position, corporations either copied it, or radicalised it and basically argued that climate change was a lie. Mobil still takes such a stance and on its website you can find slogans as: “Are we really changing our climate for the worse? ... Stop, look and listen before we leap. Reset the Alarm!” But once the Kyoto Protocol was signed, some of the oil and car market leaders decided to adjust to the situation. Corporations started to sound like villains, now that governments had demonstrated that they were taking climate change seriously. And, with the oil market already in trouble (due to dropping oil prices among other factors), they needed governments and consumers on their side. Corporate spokesmen received new orders and material, and fancy looking websites were launched. On further consideration, climate change appeared to be perfectly suited to a corporate exercise in good consciousness. The diversity of climate data in circulation and the complexity of the climate problem serve corporate strategists well. They allow them to fiddle with statistics, to downplay the role of the oil industry in causing the problem, and to overplay their remedial actions. Shell’s website informs us: “Burning all known oil and gas resources would lead to atmospheric CO2 levels well below the EU target.” That would be true, were no other CO2 producers (coal, for example) to exist. BP’s site presents percentages of emission reductions “showed by the BP group’s underlying performance”. Looks promising, except that the gases listed are both marginal to BP production processes and to climate change; CO2 isn’t among them. Thus, contrary to ‘.gov’, ‘.com’ has no problem at all with the uncertainty surrounding climate change. By fostering this uncertainty, they can commit to the cause while holding back from committing to it. Shell again: “the tremendous uncertainties make it difficult to assess climate change, more research is clearly needed”, but also: “given the risks and uncertainties, it is clearly prudent to reduce the environmental impact of producing and burning fossil fuels.” Uncertainty allows Shell to maintain its scepticism while acknowledging the problem all the more generously.

By emphasising that climate data only allow for tentative conclusions, corporations create the time-frame necessary to incorporate the environment into their business on their own terms. Shell’s recent investments in the electric car, Ford’s call for understanding that “we cannot claim true environmental victories without claiming marketplace victories”, or the proposal for a global emissions trading market (where big companies buy emission rights from small companies) made by the industry as a whole, all point to the same obvious thing: now that the environment is on their backs, corporations are determined to make a profit out of it. As RTMARK puts it: “the point of Shell.com is only to show that Shell cares, that Shell is good, that Shell likes people, and that people should like Shell.” Although a multinational can undergo a thousand beauty treatments, business is business.

But there are things these reductions of eco-action to money-profit overlook: in their enthusiastic commitment to environmental values, corporations have become environmentally accountable for their actions. Their embrace of eco-values might have made it harder for critics to oppose the corporate moral stance, but it also makes corporations more vulnerable to criticism of their deeds. It will be difficult for corporations to ignore evidence for the ecological trouble they are causing when they themselves label their policy ecologically correct. Thanks to the corporate eco-revolution, counter-expertise has become an extra powerful tool.

A Hard Job for the Committed Others

Counter-expertise comes in many forms: a mission to the oil fields of Nigeria, a forgotten government report quoted in the popular press, farmers’ testimonies on the changes in the soil, water and people around Sellafield, WWF’s editing of remote sensing data on Indonesian forest fires. Counter-expertise derives some of its importance from the fact that it presents knowledge claims that are ignored by the voices that dominate the scene. That is to say, the facts, perspectives, and hypotheses that counter-experts bring into circulation are especially relevant in the light of the kind of claims the big players make. Relevant counter-expertise is expertise that takes into account what the big players say, do not say and cannot say. Counter-expertise presents an approach to data that ‘.gov’ and ‘.com’ aren’t capable of.

Despite the efforts of governments and corporations, they still don’t really know how to deal with the future events that endlessly edited and adapted eco-data disclose. Neither party is very good at feeling compelled by data which only points at potentialities – they’re bad at turning tentative statements and probabilities into incentives for institutional change. In this light it becomes especially important for all those committed others to advocate such institutional changes, to work on convincing .gov and .com that eco-data don’t and won’t hand them unambigious diagnoses from which the right cures will naturally follow. The tireless indication of trends and tendencies that eco-data provide calls for changes which are much more open-ended and therefore all the more thorough. To confront governments and corporations with the absolute certainty that the End of Planet Earth is near doesn’t seem a particularly effective strategy to me. Governments take the view that certainty would make their work far easier and corporations will point out how ambivalent the signs of doom are. Eco-data do not reveal simple and irrevocable facts that make it obvious that precisely this or precisely that has to change for everything to be okay and fine. They point at something that is just as hard to pin down as the data are themselves. Eco-data seem to demand different ways of producing and governing, for changes inthe corporate and the governmental lifestyle.

Noortje Marres: xnoortje.marres AT janvaneyck.nlx

Sources:

Adbusters, No. 24, Winter 1999

Boehmer-Christiansen S., “Political Pressure in the Formation of Scientific Consensus”, in: Emsley J. (ed.) The Global Warming Debate, The Report of the European Science and the Environment Forum, ESEF, 1996.

Lash S., Szerzynski B. and Wynne B.(eds.), Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology, Sage, 1994.

Bruno Latour, Pandora’s Hope, Harvard University Press, 1999. Eveline Lubbers, “The Brent Spar Syndrome”, in: Read Me!, Autonomedia, 1999.

New Scientist, No. 2172, 6 February 1999.

Richard Rogers, “Playing With Search Engines”, Mediamatic 9#3, 1998

Andrew Ross, Strange Weather, Science and Technology in the Age of Limits, Verso, 1991.

[www.bp.com][www.chevron.com/environment/peopledo/index.html] [www2.ford.com/environment/enviroindex.html][www.ipcc.ch][www.mobil.com][rtmark.com/shell.html][www.shell.com/c/c21.html][www.texaco.com/default.htm][www.unfccc.de/]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com