Art Basel 34

Art Basel is an empty display case open for occupation by smooth commercial operators, gullible wannabes and tactical artivists alike. Here Gwynneth Porter explores the fair and its surroundings, a setting in which the uneasy relationship between money, culture and Swiss cheese is played out

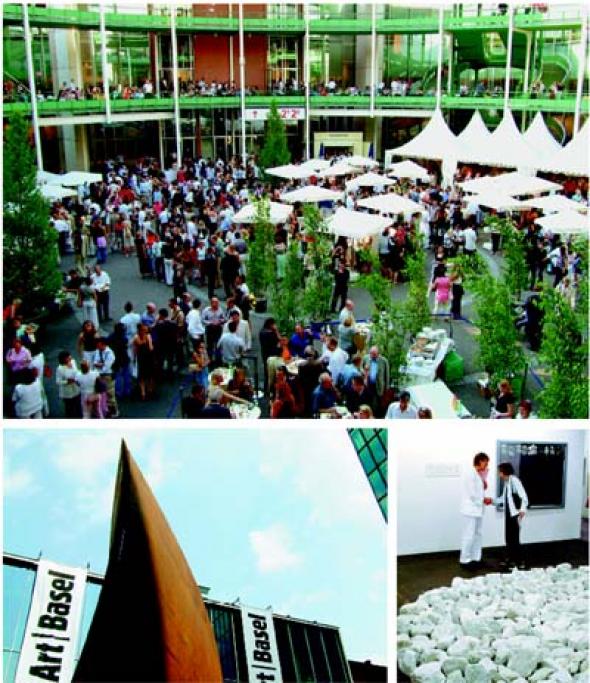

The Basel art fair is the hardcore. For a week each June, what would seem to be the entire international art mafia gather in this polite, affluent, Medieval-yetinsipid Swiss city, and has done so since 1970. Overwhelming in scale and tone, it is a vast event occupying two levels of a massive events centre, that positively (and creepily) haemorrhages money. Not surprising, given that Switzerland is surely one of Europe’s richest countries. There is also the odd feeling, when walking about, that beneath the pristine footpaths are vaults full of currencies that the Swiss don’t ask too many questions about.

When traveling, one’s choice of siesta literature can turn out to be fortuitously coincidental. For example, reading Jean Genet’s A Thief’s Journal in Basel imparted the information that Genet thought Switzerland was the obvious place for him to go when he had decided to attempt suicide. No reason was specified, but there is an undertow in Basel that was dark in an efficient, folksy, painted-wood sort of way. It was in Switzerland that Genet wrote his remarkable play The Blacks, where he declared that in this country he ‘was tired of everything being white – the people, the snow…’ One naturally gets to wondering just what creates this undertow. Well, for one thing, it is hard to escape cheese in Switzerland.

Everything comes with cheese, and the onslaught is relentless – morning, noon and night there is cheese. But what many people don’t know is that cheese contains a chemical called tryptophan which makes people dream, and hard. This chemical is in particularly high concentrations in, you guessed it, Swiss cheese. Was this the reason that such important research work into the inner recesses of the human psyche was done in Basel? Jung, Nietzsche and Kraft-Ebbing all lived and worked there as does the inventor of LSD, Dr Albert Hoffman. Does this make Switzerland a key spot to visit if one wants to ‘feel the noise’? Meet the dead? Get mythological? Meet thy maker? Go to hell?

Take Jung for example. He was less interested in the ‘little’ personal unconscious that Freud had posited, but in a collective unconscious that spanned not only individuals, but the past, present and future. His theories had been very much influenced by his strange and lucid dreams – not a surprising thing for a Swiss, assuming he had a typical appetite for cheese – both asleep and awake (which are of course not entirely separate conditions). During one of his visions, in 1913, he witnessed a ‘monstrous flood’ swamping Europe. Many drowned and cities crumbled. Then instead of water, blood streamed everywhere and Europe was plunged into a winter that went on and on. This was in mid-July. On 1 August, World War I began.

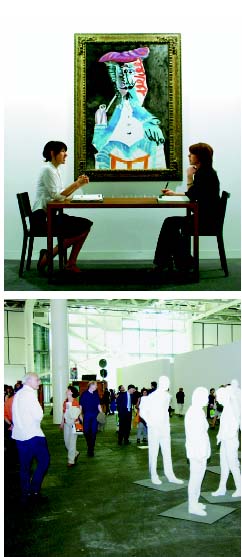

But Art Basel clearly has no time for neurosis of any kind. The fair – ostensibly the face of untroubled art commodification – is no place for the weak, conspicuous displays of confidence being necessary to attract backers. The women were particularly amazing. To get around such an expo was quite an undertaking, and doubly so given the heat-wave outside and post-Venice Biennale fatigue, even if one was wearing sensible footwear. But all around was this special breed of incredibly slickly turned out women in little strappy designer heels and not wincing at all. The female gallery assistants/bitches, or gallerinas, were particularly inscrutable. The general effect of such an art fair is that of a thousand glossy art magazines come to life. In the same way that these magazines seem to pretend to show you everything worth showing, the fair purported to deal in only the most important artists, as if what was left out was not worth including. In reality there is a hell of a lot of great work missing, as what usually makes it into art magazines and fairs is that which, in the case of magazines, pays for advertising and, in the case of fairs, is predicted to meet the taste of the target markets. Much art, for example, is still bought with a mind to décor.

Something else about art fairs is that there is a quite different relationship between work and viewer than, say, when visiting an art museum or gallery. Where the latter tend to aim for coherent displays with some sort of narrative art fairs, for better or worse, are entirely incoherent. And one tends to expend more energy blocking out work one does not want to see than on engaging with the interesting work. There is such a weird admixture of periods, formats and styles that, on this sort of scale, it’s draining to the point of being damaging. But that is not to say that there was no narrative in operation at Art Basel. There was one and it was all to do with the aura of art, investment potential, general prestige, and high finance.

The fair is organised into two main parts: the Art Galleries section occupied by the dealers displaying a cross-section of the artists in their stables, and the newly introduced Art Unlimited area. This ground-floor display is devoted to what could be described as museum-scale works by the hottest dealers; hottest in the minds of the organisers. Dealers, within their booths, also have the option to choose to devote space to single artist projects by ‘young artists’ – a sort of overlap between the two main sections called Art Statements. This year there were seventeen such showings. The outstanding work and booth of the fair, I believe, was that occupied by China Art Objects Galleries. This Los Angeles gallery-cum-project space, started as an experiment in 2000, was included in the Basel Art Fair for the first time this year. Their booth was quite the exercise in subversion, participating in and aping the Art Statements format brilliantly. CAO turned their space over to an installation by the disarmingly clever Los Angelesbased African American artist Eric Wesley. In the space one encountered a nice new red cylindrical sandblasting unit atop a pile of sand. There was a painting which, upon close inspection, turned out to be stretched denim that had been blasted in a focused fashion. There was also a rack of jeans. According to the capitalised, hand-written, corner-stapled A4 handout, it is a work which proceeds from three premises: firstly, that sand is the embodiment of time; secondly, that ‘people love those fake worn jeans because of guilt, i.e. you work at the computer all day leaving your body behind, you know you should be working with your hands so you compensate by displaying your obviously constructed ‘dirty’ jeans’; and thirdly, the idea and impossibility of starting over, of erasure.

The handout also talked about how, when the machine runs, it sends Malibu sand out into other booths to settle on the tops of paintings and into DVD players. As a series of saleable items in the space there was an edition of 17 ‘homeland security style survival kits’ for Art Statements participants – sets of rolled up plastic sheets stuffed inside rolls of duct tape for those booths that wanted to protect themselves, all of which sold it seems. (Duct tape is an interesting social artefact: before the Gulf War the American public was urged to buy it in case of terrorist attacks, then it emerged that Dick Cheney would profit hugely from a run on this product. There seems to be an interesting point of contact here in terms of the way dealers ‘talk up’ artists they have themselves invested in.)

Wesley’s work was a welcome relief in that it was site-specific (or should I say spite-specific?) and articulate. The rest of the work in the fair was so autistically non-site-specific, so passive, so mute. Such a presentation was yet another feather in the souvenir headdress of this astute gallery, one that has charted a radical course through the grey area between the extremes of the historically anti-commodity artist-run gallery scene, and the dealer gallery sphere. Radical because, unlike the depressing commercialism and intellectual sloppiness of a standard gallery operation, CAO sought to actually do something for their community of talented artists.

In the same way that art exists in the face of a lot of things, this gallery project has sought to act in the face of the financial terror many artists experience. LA has some amazing art schools, but graduate students leave them with horrifying levels of debt and face the distinct possibility of hideous compromise to survive economically. Given these circumstances, the idea of making money for artists you love geniunely was surely a great and timely one.

One of the founders of China Art Objects Galleries, the late Giovanni Intra, had left New Zealand in 1996, where he had been instrumental in the excellent Auckland artist-run space Teststrip, to do something stupid and expensive that would no doubt result in something charming, successful, and sure to expose conservatism in thinking. In an article written for the 2001 exhibition Circles in Karlsruhe, Germany, (ostensibly about artists’ circles), Intra explained why pure abstinence from the financial scene was counter-productive: ‘The shift from alternative venue to something more economically opportunistic – from simply exhibiting artists to representing them – wasn’t the result of a gradual change in principle, but a conscious adaptation in order to best exploit the potentialities at hand… We have discovered, after years of research, that money doesn’t compromise an exhibition programme. If I keep returning to this ‘alternative’ point it is because of the pleasure I have taken in betraying its principles. Selling art is a lot of fun. To make money out of art is a kind of revenge against the expense of graduate education and the political imperative which suggests that it is compulsory for young artists to attend school for extended periods and go into debt… Most days there’s a lot of laughter in our gallery, and it often surrounds the perversion of the art system and our part within it.’

Perhaps they are playing with the oft-quoted idea from Negri and Hardt’s Empire that ‘there is no outside’ when it comes to capitalism, or maybe not. But one thing was for certain, there was no point in going outside for long at Art Basel because it was too damn hot. The interior spaces of the exhibition centre were of course luxuriously air-conditioned, and the astounding dumbness of this coolness made the Basel art fair, in my mind, even more of a sinister social text. This feeling was compounded by the selection of the winning pavilion at the Venice Biennale the week before. As far as we could make out, the only reason Luxembourg won was that their show, Air Conditioned, lived up to its name and, unlike the rest of the Biennale, remained beautifully cool during a comic heat wave. I can understand why taking advantage of this milieu would appeal so much to these cunning community-minded young gallerists – but as Intra once quipped, ‘it’s not exactly riding the jock of genius.’

Gwynneth Porter <Gwyneth.Porter At manukau.ac.nz> is a writer living in Auckland, New Zealand. She is also a member of the itinerant artist-run gallery project, Cuckoo

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com