Anti-Viruses and Underground Monuments: Resisting Catastrophic Urbanism in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is besieged by elite-backed architectural mega-projects and micro-interventions. Dmitry Vorobyev and Thomas Campbell describe the dominant strains of 'renovation' and the popular resistance to them arguing that, in St. Petersburg, class conflict takes the form of opposed visions of urban renewal and historic preservation

The world’s great cities periodically undergo waves of rapid architectural and infrastructural development. While Petersburg slumbered in the 1990s, its older sister and rival for the title of Russian capital, Moscow, was undergoing a total makeover under the often-autocratic leadership of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov. Moscow’s city center was devoured by an endless series of office buildings and shopping plazas, and the whole city was cut to ribbons by a set of ring roads meant to cope with the growing traffic. Luzhkov and his team even went after the city’s subterranean and symbolic spaces. The space beneath Manege Square (right next to the Kremlin) was turned into a gigantic underground shopping mall, while the square itself was transformed into a riotous ‘public art’ installation — of kitschy, bronzed Russian fairy-tale characters — by Moscow court sculptor Zurab Tsereteli. Moscow’s makeover was achieved through a fusion of political power and economic clout, thus setting the mold for the future Putin ‘power vertical.’ So it is no accident that Luzhkov’s wife, Elena Baturina, headed the Sistema Corporation, which has become the major construction and development subcontractor not only in Moscow, but also throughout Russia.

Meanwhile, the inattentive visitor to Petersburg might have been forgiven if he claimed that nothing was happening there at all in the ’90s. Although a former Soviet-era construction business boss, Vladimir Yakovlev, took over the city government from perestroika-era ‘democratic’ superstar Anatoly Sobchak in 1996, most major construction took place on the far fringes of the city’s expanding bedroom communities. Construction of the city’s first ring road was launched, and work was resumed on the ill-starred project to build a dam across the Gulf of Finland to protect the city from the devastating floods that have plagued it throughout its 300-year history.

In the city’s historic center, the only thing our observer would have noticed in the way of planning innovation were the first so-called pedestrian zones, on Malaya Konyushennaya and Malaya Sadovaya. Unfortunately, their ill-conceived design made them nearly dysfunctional. They also displayed in vitro some of the worst features of the new-style Moscow approach to urban planning, which relies on showy presentation rather than a consideration of the life ways of locals and the specific history of places. In the bad old Soviet days, Malaya Konyushennaya had sported a tree-lined boulevard filled with park benches. Now it was utterly denuded and depopulated. In place of trees, benches, and people, Petersburgers were offered kitschy sculptures à la Tsereteli and the total extinction of other amenities: not only park benches, but also the indoor public toilet that had once been there. It is no surprise that, in the current consumerist boom, this ‘pedestrian’ zone has now become a makeshift parking lot. Like the pedestrian zones that have been constructed in other districts of the city, Malaya Konyushennaya is also an utterly surveillable and controllable place, an eminently ‘safe’ place. In fact, it is a non-place.

The Yakovlev team was a parodic version of Moscow’s powerful Luzhkov/Baturina syndicate. Yakovlev’s wife, for example, headed a company that produces artificial paving stones for sidewalks. (Here, the rich and powerful showed rare ecological sensitivity: Mrs. Yakovlev’s paving bricks are partly manufactured from the waste produced by the city’s five million inhabitants.) No one should have been surprised that the city undertook a massive program of sidewalk reconstruction. Likewise, the utter neglect that the city’s once-excellent public transportation network suffered during this period might have been linked to the fact that Yakovlev’s son was owner of a private mini van company. These so-called marshrutki, known for their sad tendency to crash and burn, came to dominate the streets and roadways during the late ’90s. They now contribute proudly to the near-apocalyptic traffic jams that are a daily feature of life in Petersburg. Meanwhile, the former so-called streetcar capital of the world has been dismantling its tramlines at a bewildering pace.

MEGAPROJECTS AND MINOR METASTASES

Architecturally speaking, the ’90s were an oasis of inactivity in a city that was originally conceived as an architectural laboratory. Petersburg has survived and thrived through a series of social and, hence, architectural revolutions: the Petrine (foundational) period, the endless grand projects and reconstructions undertaken by his imperial successors, the October Revolution, the Stalinist period, and the postwar reconstruction and building boom. Petersburg’s various rulers, architects, and city fathers were seemingly conscious, however, of their participation in a great historical and aesthetic project, and so they attempted to reconcile innovation and tradition. They considered it important to observe the ‘ensemble’ principle when designing or redesigning neighborhoods. They also recognised the need to conserve the look of districts and the city as a whole. Perhaps the most important formal and legal component of this conservatism was the building code, which restricts the height of new buildings to less than forty-eight meters. Just as every local architectural ensemble has a ‘dominant’ or focal point, so the city as whole would be dominated by such landmarks as the Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, and the Hermitage. In the one hundred and fifty or so years since this height regulation became the law of the city, only the occasional smokestack has been allowed to violate it.

Another vital element of this conservationist mentality was the city’s highly educated populace, who through all the peripeteia of political and social life loved and cherished their city as it was handed down to them. From the critics and artists of the World of Art movement in the early twentieth century to the numerous amateur local historians of the post-Stalin period, Petersburgers have rediscovered again and again the vast architectural treasures the city holds and found in these rediscoveries a source of inspiration and moral resistance. It is thus no coincidence that the grassroots political activism of the perestroika era began, in Leningrad, with the spirited and open defense of two architectural landmarks: the Angleterre Hotel; and the house of Baron Anton Delvig, a poet and friend of the national poet Alexander Pushkin. The core of the resistance was a group of young archaeology enthusiasts who had met in the Central House of Pioneers and Schoolchildren, a hotbed of youth creativity and freethinking during the 1960s and '70s. This ad-hoc network came to be known as the Salvation Group. It is worth nothing that their avowedly ‘apolitical’ aims were perceived by the powers that be and society at large as a threat to the established order.

Lacking the means and the will to do otherwise, Sobchak and Yakovlev left Petersburg more or less the way they had found it. The organism of the city, then, has always been to assimilate or resist architectural ‘viral’ attacks on its unique albeit contested identity. However, in the new era of Putin and his ‘Petersburg team’ in the Kremlin and a new (now, non-elected) ‘governor’ in the mayor’s office (Valentina Matvienko), our once-lackadaisical visitor will have become more than alarmed at the rapid alterations imposed on the city’s built environment. To many witnesses and innocent bystanders, in fact, this change has come to seem positively catastrophic. Many of them wonder whether the city will be able to resist this new wave of ‘inevitable’ change. Will Petersburg finally become something that it never has been — a really bad (rather than truly inspired) imitation of ‘all the best’ in international architectural practice?

Gazprom Skyscraper proposals

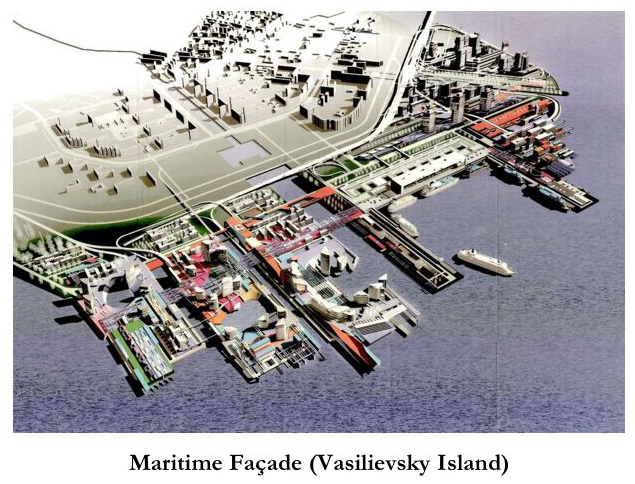

Our incurious but now anxious visitor might find an answer to our questions in the window of the writers’ union bookshop on the city’s main street, Nevsky Prospect. There he’ll find for sale a two by three meter laminated map of the city. What’s unusual about this ‘satellite’ map is that it shows him things he can’t (yet) see in the real city: a new passenger port and business/residential district on an artificial island to the west of Vasilievsky Island; a super-highway running from north to south through this fantasy island; a new business complex on the confluence of the Okhta and Neva Rivers, with the Gazprom skyscraper its crowning jewel; and, finally, a completed ring road. What should he make of this counterfactual map? This strange map is obviously a peculiar form of symbolic pressure or propaganda. It is designed to make the spectator accept the inevitability of the 21st-century upgrade that the new Putin-era powers that be have installed in the still-living, resistant body of Petersburg.

Winning Gazprom Skyscraper Project (RMJM London Limited)

Under the new Russian electoral system, voters in parliamentary elections no longer vote for specific candidates to represent the districts where they live. Instead, they vote for party lists, which are headed by ‘locomotives’ — i.e., well-known politicians or celebrities (like world champion figure skater Yevgeny Plushenko or world-famous Russian president Vladimir Putin) who may or may not decide to sit in parliament if their party wins seats there. Likewise, the new siege of Petersburg is being led by an avant-garde of ambitious architectural mega-projects whose viability, utility or aesthetic honesty might be doubted. Among these projects are the Gazprom City skyscraper (now renamed Okhta Centre), the so-called Maritime Façade, the Ring Road and Western High-Speed Diameter Road, the Petersburg Defensive Dam, the Baltic Pearl and Silver Valley business/residential districts, the Constantine Palace/Strelna area development, the Orlovsky Tunnel, Sir Norman Foster’s New Holland redevelopment, an observation tower on nearby Labour Square, a new state-of-the-art football stadium on Krestovsky Island, and the reconstruction of the Senate and the Synod, which will now house the country’s Constitutional Court and the Yeltsin Memorial Library.

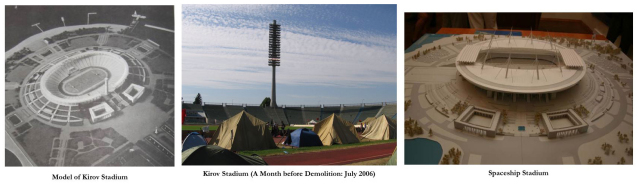

It’s quite possible that some of these mega-projects will be completed in time. Many experts, however, fear that some of them won’t be realised and that their ultimate purpose is to pave the way — legally, logistically, politically, ideologically — for the total capture of public and supposedly privately owned space by a consortium of high officials and powerful business interests. Just as important for their collective fortunes are other forms of ‘modernisation’ (or ‘aggressive development’, as Governor Matvienko has called it.) This modernisation comes in four basic varieties. The first type is the large-scale ‘avant-garde’ projects we’ve just listed. The second type is ‘capital renovation’ of existing historical landmarks and micro-districts. Sometimes, these two types of modernisation are combined. For example, the Kirov Stadium (built in the 1930s by a team of architects headed by local constructivist hero Alexander Nikolsky) has been demolished to make way for Kisho Kurokawa’s ‘spaceship.’ New Holland, one of the most mysteriously beautiful albeit inaccessible parts of the city, has been gutted so that Norman Foster can fill it with good cultural fun and high-end shopping. Farther afield, the city administration has recently proposed knocking down all the Khrushchev-era housing blocks in the outskirts and erecting new ‘more comfortable’ dwellings in their place.

Whereas this second type of renovation generally involves symbolic and/or actual castration of the city’s built history, the third (and perhaps most widespread) form of invasive modernisation can be loosely described by the term infill construction. In Petersburg Russian, the term is uplotnitelnaia zastroika, which more nearly captures the real physical crowding involved in this practice. Under the Soviet regime, the migration of workers and peasants into the major cities (especially Leningrad) triggered a housing crisis. The crisis was partly solved through the practice of uplotnenie — that is, de-privatising the single-family flats of the bourgeoisie and turning them into crowded, multi-family communal dwellings. Nowadays, the spirit of uplotnilovka has infected the construction and planning business. Parks, empty lots, and small squares between buildings have become fair game for new construction and land-hungry developers. Not only do green spaces, sunlight, and clear views disappear in the process, but older buildings are also sometimes threatened. Especially in the center of Petersburg, geological conditions are so unfavorable that the stress caused by demolition, excavation, and construction frequently causes collapse or severe structural damage in neighboring buildings. Uplotnilovka is not only limited to interstitial spaces. Developers have also taken to (illegally) adding new floors or penthouses to old buildings. They also construct wholly new buildings on top of such ‘space-wasters’ as aboveground metro stations. Thus, a so-called business/shopping complex, pretentiously named Regent Hall, has swallowed up the Dostoevskaya metro station on Vladimirsky Square. It also threatens the ‘dominance’ of the graceful Our Lady of Vladimir Cathedral, which stands directly across the street from this faux-neoclassical monstrosity.

All these forms of modernisation, urbanisation, and development are characterised by a high level of aggression towards the historical built environment, which is viewed as ‘old-fashioned’, ‘outmoded’, ‘decrepit’, ‘underutilised’, ‘inefficient’ or ‘economically ineffective.’ This totalising approach now extends even to such ‘innocent’ (insignificant) or ‘sacred’ spaces as sidewalks, façades, the airspace between buildings, and the city’s historic central squares. Our visitor will constantly be tripped up (often literally) by incongruous physical and visual impediments as he strolls the city. Everywhere he’ll encounter cars parked on sidewalks, a ranked army of street-level billboards and info stands, classical façades groaning under a mass of signage and marquees, portable toilets planted next to cathedrals, and aerial banners advertising everything from striptease joints to ‘Plan Putin.’ Such ‘minor urban metastases’ are the fourth and possibly most insidious type of catastrophic renovation.

Saint Petersburg Parking

Of course, Petersburg has finally been integrated into the commercial globalising world, and this brings with it modern methods of advertising and modern forms of urbanism. Often, however, this massed attack against the ‘old-fashioned’ city dweller achieves an unintentionally comic or ironic effect. For example, as workers struggle to remove the ‘inefficient’ tram lines that impede the free flow of traffic on city streets, on those same streets other workers erect billboards celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of the Petersburg tram network. In another district of the city, trees are being cut down to make way for new buildings. Our now-attentive flaneur will notice that right next to this scene of eco-destruction stands a gigantic pastoral public service advertisement enjoining citizens to ‘Keep [their] city green.’

What is behind this comedy of errors? Clearly, the municipal authorities want to square the circle — that is, they want to have a modern city ‘just like people have’ (to invoke the common Russian expression). And yet standing squarely in their path to progress and prosperity are two unpleasant realities: the ‘outmoded’ and ‘inefficient’ historic city itself and its numerous, sometimes ‘backward’ inhabitants.

How do the authorities imagine a modernised, 21st-century Petersburg? The word they themselves often invoke is megalopolis. In keeping with the long tradition of Petersburg eclecticism, the megalopolises they cite with admiration are the most varied and contradictory. For example, the current Vasilievsky Island shoreline has to be replaced with the Maritime Façade (they say) so that visitors arriving on cruise ships will be reminded of New York City. On the other hand, a Japanese architect and a Chinese investment/development company are summoned to the city to conjure the Asian economic miracle via such massive totem poles as a football stadium and a high-rise ‘Chinatown’ (the Baltic Pearl district). A central hero of late-Soviet society was the Soviet version of Sherlock Holmes, and so ‘Sir’ Norman Foster is invited to bring Petersburg a little closer to London. Meanwhile, this paradoxical and overweening desire to ‘bring civilization’ to Petersburg impels city bigwigs to gather a virtual who’s who of international architects (Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Herzog & de Meuron et al.) to do something as ‘big and pretty’ on the banks of the Neva (i.e., the Gazprom skyscraper) as their brother Norman did so famously on the banks of the Thames.

It is easy to understand the logic that dictates the official vision of the city’s future. The city has hosted such recent international events as the G8 summit and the Russian Economic Forum. Under its favorite son Vladimir Putin the city has also been returned some portion of its former capital status. The city’s movers and shakers thus want to present visitors and honoured guests with an image of a resurgent, modernising, economically powerful Petersburg that is also the indisputable heir to the imperial and Soviet legacies. And it’s necessary to provide visitors with a pleasant picture and a good time.

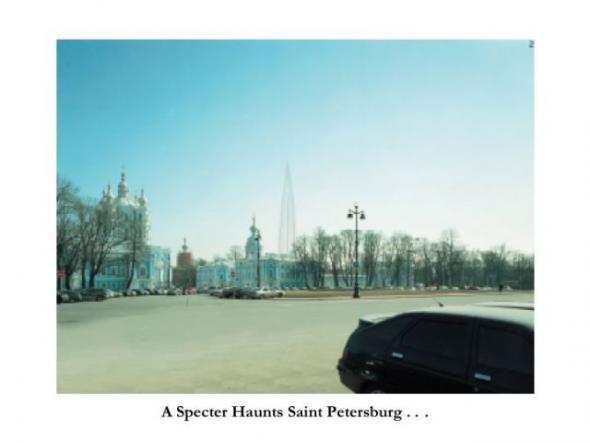

BANANAVISTS AND BAKHTIN

But there is something wrong with the picture they paint. UNESCO has recently threatened to remove Petersburg from its list of World Heritage sites. Local architects have produced a series of open letters and petitions calling on the city government to retreat from its most ambitious avant-garde projects, especially the Gazprom skyscraper. Along with such prominent local architecture critics as Mikhail Zolotonosov, they have also pointed out that the disappearance of ‘rank-and-file’ eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings as the result of uncontrolled infill construction does as much damage to the city’s visual integrity and historical continuity as will the appearance of Gazprom’s 300-meter glowing ‘corncob’ across the river from Bartolomeo Rastrelli’s baroque masterpiece, the Smolny Cathedral. Even more indicative of the disjuncture between officialdom’s ‘renovationist’, ‘progressive’ vision of urban development and public perception is the fact that the main slogan of the world-famous Marches of the Dissenters that jolted Petersburg in the spring of this year was, This is our city!

What has caused ordinarily apolitical Petersburgers to swell the ranks of protest movements headed by political parties whose ideologies otherwise leave them suspicious or cold? The multi-pronged viral assault on the city on the part of bureaucrats and developers that we have briefly described. Strange as it may seem, in contemporary Petersburg, class conflict has been translated into opposed visions of urban renewal and historic preservation. It is precisely the preservation of Petersburg as a gigantic open-air architecture museum and the very particular places people live (with their unique ‘ensembles’ of stairwells, courtyards, archways, streets, squares, and local curiosities) that has become the point around which a more general sense of rampant social injustice has crystallised. A shattering series of crimes and indignities have been visited upon the bodies of Petersburgers in recent decades: widespread corruption, police violence, bureaucratic abuse, racist and xenophobic attacks, the dismantling of the social safety net, alcoholism and drug abuse, a high mortality rate, environmental pollution of all sorts. And yet, since Soviet times, all these risks and dangers have usually been felt to be part of life’s grim ‘common sense’ and thus inaccessible to sustained critical reflection or direct collective intervention.

Why do we see mass mobilisation in defense of the city rather than against such widespread albeit de-individualised injustices? Is it because the destruction of the city is something specific — a matter of real, lived places, places that can be seen and touched and remembered? Is it because the threat of injustice now takes the form of an alien skyscraper on a horizon that used to be peacefully uncluttered? Is it because people wake up one morning and find a fence erected around the humble square where they used to walk their dogs and play with their kids?

The answer to these questions would seem to be yes. First, the now ubiquitous and visible destruction of the city its residents are used to (which includes ‘unbecoming’ tree-filled green spaces in late-Soviet housing projects as well as neoclassical masterpieces), which we have likened to a kind of cancer or virus, has provoked an ‘anti-viral’ reaction. This reaction has taken very different forms. Future activists have followed a number of routes to mobilisation and collective action. Moreover, their first experiences of political engagement, while not always successful, have usually been ‘safe’ enough to encourage further involvement. The usually high threshold to political participation amongst ‘apathetic’ post-perestroika Russians has thus been lowered considerably.

The movement to save Petersburg can be divided into two camps. Borrowing the now-accepted usage, we can describe the first camp — people who respond to concrete threats to their own surroundings — as NIMBY activists, that is, Not in my backyard. When local residents are confronted with unexpected, sudden threats to their own buildings or squares, their first reaction is often pure shock. Shock sometimes gives way to concrete attempts to defuse the threat and defend their territory — via direct actions ranging from letter-writing campaigns and legal suits to nonviolent demonstrations and ‘ecotage.’ The second camp can be described as proponents of a more strategic, holistic approach. They are BANANA activists — that is, Building Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone. Unlike NIMBYites, Petersburg BANANAvists are engaged in drafting legislation, building activist networks, educating citizens on their legal rights and training them in methods of public participation, developing new forms of generating public awareness, and devising new protest tactics. Like their counterparts in other countries, such activists are horizontally integrated with environmentalists, civil rights activists, and alt-media practitioners in other parts of Russia and the world. After a very brief but productive period of intense activity (four or five years), the lines between these camps have begun to disappear. Many NIMBYites have translated their specific experience of neighborhood struggle into a more general knowledge of legislation, the courts, and effective media tactics. Likewise, BANANAvists have strengthened their theoretical grasp of the overall situation through intense, active participation in particular local struggles.

Petersburg NIMBY groups are usually identified by the names of the districts they defend. The most well known of these groups are Okhta Bend, Defend Vasilievsky Island (ZOV), Pulkovskaya Street, Svetlanovskaya Square, Aviators Park, Muzhestvo Square, and Yuntolovo SOS. Most of these groups have similar histories, and up to the present they have defended their ‘home’ territories with mixed success. For example, ZOV brought together residents of the western, seaside edge of Vasilievsky Island, who had learned that their unobstructed views of the Gulf of Finland would be occluded by projected new high-rises. Over time, they came to learn that the city had more serious plans for the island: sand and earth would be dumped into the gulf and an artificial island would be created from scratch. As the group matured, they gained more investigative skills and widened their network of contacts with other local activists and ecologists. Thanks to their efforts, Petersburg society learned about this half-hidden project and about the legal and other shortcuts municipal bureaucrats and developers were taking to force its ‘smooth’ realisation. Another example is the initiative group formed to defend the square on Pulkovskaya Street, in the south of the city. After a series of protests, local residents realised that they were captives of the municipal administration’s planning policies. So they carried out several ‘carnivalised’ actions in order to problematise their dilemma.

The focus of Petersburg’s several dozen BANANA movements is more differentiated. The Citizens Initiatives Movement has clear communist sympathies, but at the same time it has invested an enormous amount of time and energy in educating and supporting fledgling initiatives groups, especially those battling infill construction. Green Wave began life as the initiative of Petersburg rock musician Mikhail Novitsky, who brought together fellow musicians and others to plant trees in squares slated for infill construction. In its three years of existence, the movement has expanded to include musicians, artists, sociologists, and journalists. They employ a variety of methods — from direct action to legislative lobbying — in tackling ecological problems from waste management to raising environmental awareness. EKOM is a group of independent experts that has been in existence for over ten years. They are involved in legislative lobbying on environmental issues, the development of new forms of public participation, and advocacy of popular control of city government. Living City is the newest such movement in Petersburg, but in the space of a single year it has become the most famous. The movement began as an internet discussion group, but it took on a non-virtual presence through a series of media-savvy flash mob actions designed to bring attention to the overall threat to the city’s architectural legacy.  All these groups and movements form a nucleus around which thousands and tens of thousands of ‘non-aligned’ individual activists and ordinary concerned citizens can express their distress at the direction their beloved city has taken. However, in a situation dominated by an often-ruthless (and ‘popular’) corporatist authoritarian regime, these groups tend to conform to three broad strategies for saying ‘no’ to the hegemonic power. The first strategy is legalism. Simply put, advocates of this strategy call on the authorities to obey existing laws and procedures. For example, in the struggle against the Gazprom skyscraper, the ‘legalists’ demand that the city’s existing height regulation be observed.

All these groups and movements form a nucleus around which thousands and tens of thousands of ‘non-aligned’ individual activists and ordinary concerned citizens can express their distress at the direction their beloved city has taken. However, in a situation dominated by an often-ruthless (and ‘popular’) corporatist authoritarian regime, these groups tend to conform to three broad strategies for saying ‘no’ to the hegemonic power. The first strategy is legalism. Simply put, advocates of this strategy call on the authorities to obey existing laws and procedures. For example, in the struggle against the Gazprom skyscraper, the ‘legalists’ demand that the city’s existing height regulation be observed.

The next strategy might be called conservative utopianism. Confronted with the ambitious ‘utopian’ designs of city planners, the conservative utopians reply: ‘It’s all good and necessary. Only let’s not build it here in the city center, but somewhere (literally) beyond the low-lying horizon. Or let’s build a better version of the same thing, only lower and in a way that does less damage to the city’s historic look.’

The third and final strategy is, perhaps, the most direct and explosive. It doesn’t conceal its total opposition to the powers that be; it simultaneously mocks the pretensions of the authorities and the economically powerful. In the philosophical sense, this strategy draws on the theories of Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin about the chronotope of the carnival, in which (anonymous) popular, grassroots humor gains a temporary victory over the dominant power by creating an inverted or hypertrophied mirror image of it. While this strategy was best theorised by a Russian, it has been rarely used by Russian oppositional activists. It has been, however, a common feature of left-wing protest round the world in the post-war period.

Despite the fact that, on its website, Living City explicitly embraces the second strategy — that is, the group states that it is not against any of the city’s big utopian projects as such — it has also made very effective use of carnivalism. Living City’s carnivalism has tended, however, to be a reaction to the absurd passing fancies of the administration. In their latest action, for instance, the group immediately reacted to news that the city is planning to turn the magnificent former heart of the Russian Empire, Palace Square, into a gigantic skating rink this winter. Living City decided to make public its ‘support’ for this initiative on behalf of all sporting enthusiasts. Armed with ski poles, swim fins, an inflatable mattress, and a basketball, Living City activists appeared on the square, where they began frantically engaging in their favorite sports. They thus drew mock attention to the fact that the authorities hadn’t yet thought to ‘renovate’ Palace Square to also make it a venue for skiers, swimmers, and basketball fanatics. Such carnivalistic actions serve to retranslate those proposals or plans of the administration that, in the view of Living City, are obviously lacking in good sense. They thus encourage the public and the media to engage in a more sustained critical discussion of such initiatives. Their mission, then, is that of a watchdog who attacks (in a fairly goodhearted way) the ethically and aesthetically problematic actions of the authorities. Their apparent political neutrality allows them to easily combine forces for one-off actions with other groups less imbued with Living City’s creative spirit.

However, such satiric interventions have their limits and often lead to paradoxical or unexpected results. We might examine, for example, how a group of activists united around the defense of the embattled square on Pulkovskaya Street, in the southern district of the city near the international airport. In this case, it had become clear that a legalist pursuit of justice wouldn’t bring the desired result because the interested parties had taken advantage of deficiencies and loopholes in existing laws and the justice system. Although the court case against the building project was still under review (it had been dragging on for two years), developers simply showed up one day and cut down all the trees in the square. Given these relatively hopeless circumstances, the activists decided to direct their anger and the public’s attention to the figure in the city administration most directly responsible for such destructive policies, Vice-Governor Alexander Vakhmistrov. Vakhmistrov is in charge of land use and urban planning policy in the administration of Governor Valentina Matvienko.

‘Saint Petersburg is too small a place for the ambitions of someone like Vice-Governor Vakhmistrov,’ the activists announced. On Cosmonauts Day (April 12), around two hundred Pulkovskaya Street residents gathered in their now-former square. Residents and activists tied a space-suited puppet of Vakhmistrov to several helium-filled balloons. Each participant was given the chance to bid farewell to the vice-governor. They then launched him on a trip to the moon, where he would be surveying new territory for building projects. Reaction to this event on the part of the media and the municipal administration was swift. Vakhmistrov and district officials publicly promised to investigate the legality of the building project. Several months later, however, they simply renewed their support for the project.

In response to this betrayal, activists decided to thank Vakhmistrov by erecting a monument in his honor on the former square. Originally, they had hoped to literally hammer another life-sized replica of Vakhmistrov into a meter-deep hole in the ground. When the head of the unfortunate faux-Vakhmistrov had disappeared below ground, the hole was to be filled with concrete and a simple plaque installed aboveground to mark the spot. The action was widely announced as the unveiling of the first underground monument in Saint Petersburg.

This time, however, the authorities were prepared to nip the action in the bud. A large number of policemen showed up to monitor the event and, if possible, arrest the organisers before they could commit their foul deed. Their attempts to identify and detain the organisers led to a series of comic clashes among them, the incognito organisers, journalists, and local residents. Despite the risks, the organisers decided the show must go on. They brought out the Vakhmistrov puppet from its hiding place and attempted to transport him to the waiting hole. The police immediately detained the doppelgänger. As they put the puppet in their police car, residents joyously exclaimed, ‘Vakhmistrov has been arrested!’ Other residents replied, ‘Yes, but it’s too bad they didn’t put handcuffs on him.’ Some time after, police transported Vakhmistrov away from the scene of his crime. The monument was, nevertheless, erected a week later. A smaller doll version of Vakhmistrov was placed in the hole and covered in concrete. There were no policemen present.

Vakhsmistrov gets arrested...

These exciting events in the life of Vakhmistrov were memorialised in a series of pocket calendars. The vice-governor’s adventures were depicted in the lubok style of folk engraving that was popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Reaction to Vakhmistrov’s symbolic burial was rather different than reaction to Vakhmistrov’s moon trip. Vakhmistrov himself said,

I consider it a sacrilege to bury in the ground not only myself, but any living person. This is stepping over the ethical line. It just underscores the educational level and morals of the people who organised these actions.

We should note that the press tended to emphasise that the organisers had wanted to bury Vakhmistrov. They also used the word chuchelo to describe the Vakhmistrov puppet — that is, a word usually used to denote the handiwork of the taxidermist. Vakhmistrov and some of the journalists covering the event thus shifted its significance away from its ‘monumental’ aspect to something that smacked of witchcraft, voodoo, and Satanism. Other members of the press, on the contrary, ironically focused on the fact that Vakhmistrov had gotten his just desserts. This same split in opinion about the action could be observed in the reaction of other activist groups. In press releases, some groups announced that, unlike the residents of Pulkovskaya Street, they would be conducting ‘normal’ demonstrations in defense of their squares, not holding carnivals. On the contrary, other initiative groups decided to erect underground monuments on the squares they’re attempting to defend. To this end, the Pulkovskaya Street activists have developed a simple kit for quick installation of similar monuments.

Neighbourhood by Pulkovskaya Street

UPGRADE AND AFTERLIFE

In recent decades, several factors combined to save Petersburg from the fate suffered by other great cities. Among them were a lack of resources and political will, historical accidents, traditions that were honored by bureaucrats and architects alike, and, finally, Petersburg’s amazing ability to harmonise and co-opt the most various architectural styles. This resilience is now being severely tested by a forced upgrade that is long overdue (or so say the city’s authorities). While this new upgrade is definitely a product of human ambitions and actions, it is transmitted like a virus: the same banal code known as ‘development’ attempts to reproduce itself throughout the entire city environment, whatever the cost to its host. Everywhere the victims of this virus will be different — a square here, a skyline there — but the overall effect is the extinction of a historical urban organism that, whatever its faults, is unique.

The virus’s activity leads to a split in Petersburg society. One group hotly defends development as a kind of transcendental good, not as a disease. The other group locates this good, rather, in a past that is both wholly imaginary and utterly tangible, and reacts violently to what it sees as catastrophic renovation. For better or for worse, it will soon be clear whose vision has won the day. At stake, however, are more than just a few thousand buildings, several dozen squares and parks, and the sentimental folk who mourn their disappearance.

POST-SCRIPT

Since we wrote the first version of this article, in November of last year, much has happened in the conflict between the defenders of ‘aggressive development’ (Governor Matvienko’s coinage) and the defenders of ‘historic Petersburg’. On the one hand, the destruction of the city proceeds apace. This apparent victory for the camp of the developers has, however, proved Pyhrric, as the anti-viral movement has shown itself capable of mutating as well.

Thus, Living City has quickly evolved beyond its original ‘reactionary’ and ‘carnivalistic’ impulses. While the founding core group of the movement mainly consisted of ‘well-meaning geeks’ (students, teachers, journalists, programmers, natural scientists, local history buffs), Living City’s principally open structure, its weekly tactics-and-strategy meetings, and (most important) its rapid rise to citywide prominence and media notoriety have made it an ‘attractor’ for other less conservation-minded Petersburgers, from otherwise voiceless local residents to, surprisingly, members of the municipal establishment itself. On Telezhnaya Street, for example, Living City aided local residents in publicising what they saw as the administration’s manipulations in declaring their buildings uninhabitable. The initial reaction on the part of the authorities was harsh: Matvienko accused the activists of being irresponsible ‘non-citizens’ who would be held liable for their meddling in the courts. Almost immediately, however, Vakhmistrov publicly admitted that the concerns of activists and residents were justified; as a result, the city would be forming a new commission to carefully monitor all new construction in the historic centre. This newfound populism proved infectious for his boss: days later, Matvienko announced that she would be initiating a ‘red book’ project (endangered species register) to document the city’s threatened ‘memorable places’. In another case, Living City found an unexpected ally in the city courts. The movement’s co-leader Julia Minutina and two other citizens filed a suit against the city’s conservation committee for allowing a skating rink to be erected on Palace Square. Unexpectedly, the judge ruled against the defendants, thus setting a historic precedent in a country believed to be ruled by ‘telephone justice’.

Meanwhile, the city authorities and their influential business partners continue – on paper, in the press, and, quite visibly, on the ground – their ‘utopian’ project of transforming Petersburg into a ‘modern European city’, using all the considerable financial and legal (and illegal) means at their disposal. Strangely, their modernisation is a return to the rhetorics and instrumentarium of the late Soviet period, when citizens were promised that they would be ‘living under communism’ within ten or twenty years, while lived reality indicated otherwise. Happily for the authorities, this new promise of ‘stagnation’, fuelled by increased consumer possibilities, is for the time being passively accepted by significant swathes of the populace.

Unhappily for the authorities, this heavy-handed modernisation simultaneously generates its own delegitimisation, systemic breakdowns and, hence, enemies. Among these new foes are the workers of the Ford auto plant, in the suburb of Vsevolozhk, whose independent union has almost singlehandedly revived the fortunes of the country’s ailing labour movement, which had been one of the prime catalysts of perestroika (along with the ecology and conservationist movements), by carrying out a series of semi-successful strikes. The ranks of these ‘foes’ also include Russia’s battered but vigorous human rights movement, which similarly interferes with the smooth execution of the regime’s new (neo-Brezhnevian) doctrine, ‘Plan Putin’; it has been revived by the skilful use of new communications technologies and an influx of youth activists.

Just as interesting, from our point of view, is the tendency of the Petersburg conservationist ‘movement of movements’ away from the NIMBYite and BANANAvist frames we have described, above, towards the search for an alternate mode of ‘modernising’ Petersburg. Their new strategy, still in its infancy, is centred on the search for ‘human-friendly’ alternatives to the totalising projects reeled out, with an ever-more noticeable hysteria, by the powers that be. On the practical level, this can mean anything from drafting a ‘homemade’ plan for rerouting a superhighway to the absurd (but acutely critical) proposal to build the Gazprom tower underground. In all cases, this search for alternatives always involves the actual analytical work (historical, legal, architectural, geological, financial, etc., research and documentation) and genuine public participation in decision-making that the authorities embrace in words but furiously impede in deeds. For Petersburg’s residents (zhiteli – literally, ‘livers’) really do want to become citizens of a ‘modern European city’, with all that entails (and some things it doesn’t.) But the authorities – unconscious disciples of Giorgio Agamben – insist that they remain bare ‘livers’.

Thomas Campbell <avvakumATgmail.com>is a translator, researcher, and writer living in Saint Petersburg. He is also a member of the Chto Delat workgroup platform [www.chtodelat.org] and a founding member of the Petersburg Video Archive (PVA)

Dmitry Vorobyev <moxabatATgmail.com> is a sociologist at the Centre for Independent Social Research, Saint Petersburg. He is also an activist in the Living City movement [www.save-spb.ru] and other grassroots urban ecology groups

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com