All Tomorrow's Parties

Veteran of the dot bomb Corinna Snyder asks if revitalising the all-day office party of the past is the key to recovery or the road to perdition

During the 90s, a wave of digital services providers emerged who explicitly imagined themselves as hip play spaces in which to simultaneously develop, and undercut, corporate structures of power. They built sites and felt politically fulfilled by the fact that the information architecture was just inherently really cool and subversive. I have worked at one for the past year.

My company rode the bull market – aggressive growth, global expansion and a wildly successful IPO. And then the ride began to slow in the 3rd quarter of last year. Now, the firm is battling the effects of an emerging recession and the associated bear market. There’s not a lot of work – not here, not anywhere. It’s hard to be playfully subversive when no one’s footing the bill. What does senior management do? Amongst other things, launch a ‘morale-building’ website. Corporate-sponsored morale-building efforts, especially ones designed to explicitly reveal employee dissatisfaction, seem inherently tragic. Like monuments, they’re incredibly rich in conception but frequently all too barren in realisation.

This effort is emblematic of more than just the flaws inherent in the attempt to create an idealised corporate culture. The new economy stance that one could succeed and subvert at the same time, both eat the rich and be the rich, has come undone if only because dot com people aren’t as rich as they used to be. In turn, I see colleagues discovering a past relationship between the company’s ‘cultural’ values and its book value, and leading efforts to reinvigorate business through the resuscitation of culture. These attempts draw on some pretty outmoded forms of cultural reproduction – forms that, it was claimed, had been radically transformed in the age of the ‘new economy’. The fashionable belief that social articulations of hierarchy and difference are now powerless as instruments of inequality but rather mere ‘lifestyle’ choices for an empowered populace is looking more than a little dubious.

The logic of a sympathetic simultaneity between cultural and economic value runs as follows. Once both were strong; now both are weak. ‘Our culture’ was trumpeted as one of the ‘core values’ that distinguished us from our competitors. So was our profitability. Now our valuation is at an all-time low, and so is the mood in the office. Once both were also thought to be transgressive; now both play by the rules. Ours was a business sector that showed such continuously anomalous relationships between established valuation ratios and stock prices that many believed that we were entering a new economic age, in which the old rules no longer applied. Now people show up on time and play golf.

But was our past culture the source of our past profit? Did our company succeed economically in the past because it broke the economic rules? Can profitability be regained by a reinvigoration of the cultural life of the past? Here, the cargo cult ideal has been made real: we are using digital communication forms to overcome a profound unease with historicity, turning back time to invoke a mythic past – one of egalitarian access to power. The moral site launches – all can communicate, but only the leader can moderate. We try to force the transient to become permanent by instantiating nostalgia for history. The call goes out by email: take off your headphones and turn your music up loud every Thursday, in the hope that the old will hear you and return to their old haunts, bringing with them herds of client buffalo. Sponsor an art month and a talent show. Act alternative, and maybe the old (new) P/E ratios will return.

Transience was once lauded – everything was changing, and that was a good thing, because a new paradigm was emerging that would shift the balance of power. Now transience is feared – everything is changing, and that’s a bad thing, because the change was supposed to create stability, not more flux. The reason we wanted to redistribute power was that we wanted more of it – not so we could upset it, but so we could wield it. So what’s new?

Corinna Snyder <corinna@ethnologic.com>

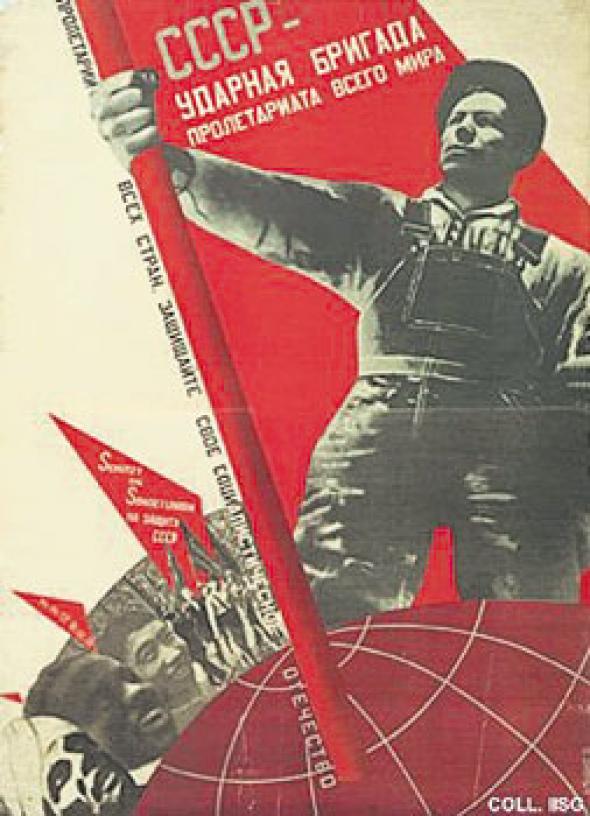

>>Images-Gustav Klutsis, 1931. The USSR is the crack brigade of the world proletariat-E. Mirzoev, 1938. A giant Stalin amid Azerbaijani peoples celebrating the anniversary of the introduction of the new constitution of the Soviet Union.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com