Airing Dirty Laundry in Public Art

On visiting ‘Art in Public Places: the Archive of the Public Art Development Trust', Malcolm Miles evaluates the role of art commissioning agencies in changing the face of public art in the UK

Public art has had a mixed reception by artists, critics, curators and the public for whom it was intended. It has been claimed as an attempt to bring art to a mass public, but also as a misuse of public funds, or the imposition of institutional taste on spaces used by diverse publics. For artists, public art offered opportunities and constraints. But the opportunities have also been seen in different ways, as possibilities for social engagement precluded by galleries and museums, or more cynically as an extension of the market for sculpture. The constraints of working with commissioning bodies in the public and private sectors - and with intermediaries such as Public Art Development Trust (PADT) - have been similarly perceived either as offering encouragement and nurture, providing the services of an office, press contacts, and project documentation as well as easing the path of negotiations over what could be a period of years from idea to realisation of a project; or as a negative interference, compromising the artist's creativity and autonomy. I revisit some of these dualisms below, but here note simply that art's autonomy was a motif of modernism, the currency of which is devalued now - when we contemplate post-postmodernism.i This raises a question, which for me pervades discussion of public art, as to whether it was a spin-off from the modernism which is epitomised by the isolated objects and white walls of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), or something else. The current exhibition of part of PADT's archive at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, UK, offers a chance to reappraise it.

Image: Julian Opie’s visualisation for the Diana, Princess of Wales memorial in Hyde Park, 2002

The archive comprises 176 boxes of papers, visualisations for projects, and maquettes. The papers include contracts, press releases, and correspondence between the agency and artists, commissioning bodies, and contractors. Most of the material has not yet been catalogued, and some boxes (or items in them) may be incorrectly labelled. A task of major proportions lies ahead, which should include transfer to digital media. But the exhibition gives a series of snapshots of PADT's activities. Some projects were more successful than others, and the issues raised are both socio-political and aesthetic. A gallery discussion on 1 July brought the material to life as artists Hannah Collins, Vong Phaophanit, Bill Woodrow and Michael Sandle gave personal commentaries on the exhibits and their contact with PADT in the 1980s and 1990s.

The discussion was introduced by curator Stephen Feeke and archivist Claire Sawyer. For Feeke, the archive is ‘a time capsule of a way of working, not only of how artists work but also how an office works.'ii This suggests that the work of organisations like PADT - one of several such agencies in the UK founded in the 1980s - is part of the past. The status of the material as an archive, too, encapsulates it in history. The question is, in which histories was it situated, and in the writing of which histories in future will it be useful. Time capsules preserve pasts, either literally by being buried in the ground or, here, discursively, re-coding evidence of everyday processes as archival data. But the contents of an archive are fragments denoting overlapping worlds the coherence of which, at the time, was shaped by wider frames of reference. Before suggesting how some of those frames might be evident in the material, I want to say a little about the exhibition and the discussion by which it was animated. Before that, I set out some of the background to the archive, in part recalling my own links to public art's structures (as someone writing on the field) in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

PADT and the Network of Commissions Agencies

PADT was founded in 1983, one of several such agencies in the UK. During the two decades of its activity, PADT worked with more than a hundred artists, from

postgraduate students to artists who have since been internationally recognised. Commissions included permanent works which extended the traditions of the art-object to outdoor sites, and temporary projects in which the aim was, in some cases, to hand over the process to local groups. This spectrum of approaches is represented in the exhibition. Handing over projects to local or other public-sector structures and groups (such as health authorities and community groups), however, largely failed to happen. Many of the sculpture commissions, in contrast, predictably given the nature of materials such as bronze and stone, remain in place. Budgets were not initially excessive, and a continuing concern for PADT was how to generate the budget for the next project - on which the continued existence of the organisation depended. In the late 1980s and through the 1990s there was a move to higher-status, higher-budget projects, and a global approach to the selection of artists. This was in keeping with a general shift from a culture of arts administration for the public good towards cultural management on a business model, in the Thatcher years.

The shift towards a managerial approach was contextualised by the emergence of the symbolic economies - economies of immaterial production in which image is key - through which cities compete globally for inward investment (often in the cultural sector or the knowledge economy) and tourism. PADT remained publicly funded, though required to run as a business based on a percentage of the project budget. As a consequence of their required adoption of a business model, public art agencies began to lobby (separately and via the Arts Council) for policies such as Percent for Art, and for art as a driver of urban renewal, by which their sector might be enlarged. The case for art as a solution to the problems of inner-city decline, or a means to revive zones of de-industrialisation, was made successfully. Art‘s expediency is now regarded by most city managements as a norm. Yet the idea of art as a cosmetic solution for problems produced by failing infra-structures, at root by other areas of government policy, was contested then and haunts public art's histories now.

Although set up by the Arts Council's regional offices to pursue regional agendas, in the 1990s, PADT and other agencies, such as Public Art Commissions Agency (PACA) in Birmingham, began to compete against each other internationally. Perhaps the directors of these organisations sought to gain the status of museum curators by working with well-known artists - public art as the gallery mixed show outdoors. There were exceptions, notably Artists Agency in Sunderland (renamed Helix Arts, and now in Newcastle), which retained its regional roots. But the general effect was that commissions became closer to big business, just as the housing of modern and contemporary art became a key element in the symbolic economies of cities such as Bilbao, Barcelona, and London.iii At the same time, an increasing number of UK local authorities and health authorities, persuaded by the rhetoric of public art which PADT and PACA promoted, appointed in-house public arts officers, reducing the need to employ agencies. In 2003, PADT's revenue funding was withdrawn, at which point it was no longer a viable business. PADT completed its outstanding projects and closed. The archive was acquired by the Henry Moore Institute in 2005, in the state in which PADT left it.

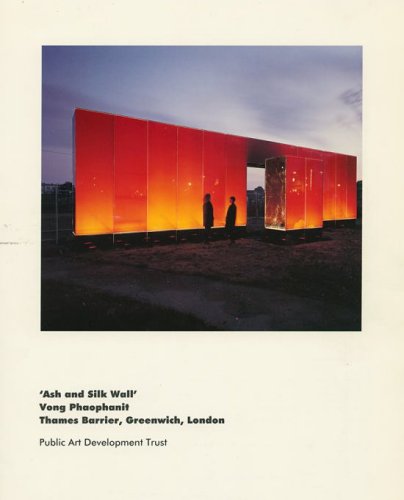

Image: Publicity leaflet for Ash and Silk Wall, Vong Phaophanit, 1993. Courtesy the artist, Leeds Art Gallery (Henry Moore Institute Archive)

Among the projects presented in the exhibition are Michael Sandle's St George and the Dragon (1988), a bronze monumental sculpture; Sarah Tombs' Sailing by Stars (1988), a welded steel sculpture sited outside Basingstoke railway station, Hampshire; Bill Woodrow's (1992, unrealised) proposal for a sculpture referencing the image of needles and threads, for a roundabout in Lewisham, south-east London; proposals by John Newling (1996) for the new Inland Revenue building at Nottingham, and by Katherina Finch 1998) for the exterior of the National Theatre, London; Hannah Collins' proposal (not dated) for a Children's Museum ‘to be created anywhere to celebrate the existence and extent of children's imagination'iv; Julian Opie's visualisation for the Diana, Princess of Wales memorial in Hyde Park (2002); and a model, with related correspondence, for Vong Phaophanit's Ash and Silk Wall (1993, destroyed) for an open site near the Thames Barrier in Greenwich. Phaophanit spoke in the gallery about the painful experience of a commission which, if well-intentioned, met with a destructive response.

A Triangulation

Three of the projects documented in the exhibition serve to triangulate divergent approaches within public art. For Hannah Collins, the site is no longer a geographical entity but the everyday culture of a specific public. For Phaophanit, the physical site is loaded, replete with evidence of the uneven benefits of urban redevelopment. And for Sandle, perhaps the site, outside an office block in Blackfriars, is a kind of history, a myth brought into contemporary and contested realities.

Collins' idea followed a commission for a north London hospital, in which she invited long-term elderly residents to contribute one item of meaning to them. The result was a wide range of objects, from key rings to postcards and items of bric-a-brac. These were placed on shelves and photographed, exhibited as large-format transparencies on light boxes in a corridor. At the time this was a progressive technology, though now such a project could use digital media to be more extensive and widely disseminated. Collins hoped that others would adopt the idea. That they did not may be explained by the pressures of institutional change, and decanting of long-term patients into community care or private nursing homes. In such conditions, projects tended to be seen as finished when the art appeared on the wall. Collins was asked by PADT to put in another proposal, in this case without a brief. The result is four boxes of objects exemplifying what might be the contents of a children's museum on a similar basis of personal donation. As Collins suggested in the discussion, the use of digital media would recast such a project outside the limitations of a physical site and bureaucracy.

Phaophanit's commission occurred quite early in his career, seeming to be a major opportunity. He related how he wanted to bring the visual aspect of the shining glass towers of redevelopment on the other side of the river - in London's Docklands - to the neglected south bank of the Thames. The glass wall was technically advanced, using laminated sheets without visible joining structures to encase silk on one side and ash on the other. From a distance the wall seemed solid, but on approach a section was seen to be detached, revealing a way through. The form has a neoclassical simplicity, while Phaophanit saw the bright orange of the silk as referencing the culture of Laos, his birthplace. This metaphor for the fragility of life was lost on local youths, who shot at the wall in its wasteland setting with air rifles. The archive includes letters from PADT to a contractor concerning the work's dismantling in 1996 (and an invoice from the contractor for £4,324 paid by the local authority). This was the kind of disaster agencies were supposed to prevent, yet predictable.

Sandle's bronze sculpture is, paradoxically, the closest of the projects presented in the exhibition to the tradition of the monument; and the most subversive. Sandle noted that in an earlier sketch he saw the dragon winning the fight, and representing Mrs Thatcher. The final version draws on sources from existing equine sculptures on the building (from the inter-war years); and memories of public monuments such as Emmanuel Fremiet‘s Joan of Arc (1874) at Place des Pyramides, Paris, which he saw as a student.v Yet Sandle's aim was to introduce another reality into a subject-matter so familiar as to be easily dismissed as a remnant of the nineteenth century. As he says, ‘Saint George is not a nice officer chap. He usually looks as if he's playing polo ... as if he couldn't knock the skin off a rice pudding. Mine is an NCO type ... a really nasty piece of work. He's got to be ...'.vi There is no need to specify the circumstances in which this NCO type acts. The sculpture invites speculation, in the guise of something conventional which becomes the opposite. At the same time, the form accommodates the architecture of the building on Dorset Rise in front of which it stands - the rectilinear windows, for instance, are referenced in the grid through which the dragon attempts to rise. Not surprisingly, a monument which Sandle regards highly is Charles Jagger's Artillery Memorial in Hyde Park, with its devastating realism.

Autonomy and Sociation

If Sandle's work annexes conflicting histories, public art might today, as a whole, be read as history. As I said above, the status of an archive confers this encapsulation, though in which past remains a question. All histories are, of course, selective, and some are determined more by extrinsic than by intrinsic factors. For some artists and critics this was a difficulty in as much as the autonomy claimed for modernist art was felt to be incompatible with working to a brief, or presenting to a selection panel of non-artists. For others, working in social settings was a means to democratise art, to take it out of the elitism of the white-walled spaces often described as value-free. Recently, artists collectives such as Freee in Sheffield or Platform in London, Ala Plastica in Buenos Aires,vii and WochenKlausur in Vienna,viii have evolved ways of working as artists while moving closer to activism. Similarly, groups such as the Yes Men work both performatively and through the internet. Meanwhile the borders between art forms such as painting and sculpture, like those between art and architecture, fashion, advertising and news media, are no longer policed. A term such as public art seems out of place in a field now often described as visual culture, while environmental activism appears a more effective catalyst to public debate on climate change than eco-art.

Image: Michael Sandle, St. George and the Dragon, Dorset Rise, London, 1987-8

This is not, however, to write off histories of public art. Part of the value of the archive is that it will enable researchers to unearth the contradictions which always permeated the field of commissioning. Since the first funding programme specific to art in public places - launched in the US by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in 1967 - there has been division as to whether a work's aesthetic quality, its representation of a site or set of conditions, or its efficacy in responding to social needs, is more important. There are cases of art in public spaces which have been successful in attracting diverse and engaged publics, such as Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans' Memorial in Washington DC. And if Antony Gormley's Angel of the North was initially received with scepticism, it gained a sense of ownership when an image of it wearing the black and white stripes of a Newcastle United (football club) shirt appeared in a tabloid newspaper. Nonetheless, a recent turn in UK cultural policy signifies what may be the end of the rhetoric of culturally-led urban regeneration, which was always a mask for property development. After two decades of public subsidy, there is very little evidence in measurable terms that public art provides solutions to de-industrialisation or social instability, and policy statements have reverted to a more aestheticist stance: Tessa Jowell, as Secretary of State for Culture Media and Sport in 2005, for example, said, ‘... what the arts do that only the arts do is most important. Out of that come other benefits, but the art comes first.'ix Perhaps her speech writer had been reading Clement Greenberg.x

Greenberg introduced a reductionist art history in which art progressed to its bare essentials, such as colour on surface for painting. The aesthetic is thence a matter of trained perception and intellectual understanding, though not devoid of sensation. In some ways, public art sought to ditch that, but at a time when art critics - notably Peter Fuller in the UK - had already begun to question art's isolation. For Fuller, responses to art revolved around deep human experiences, such as the unconscious memory of a potential space between a mother and an infant, discussed by psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott.xi Fuller saw this alluded to in the deep space of paintings by Mark Rothko and Robert Natkin, and later in more obvious ways in pictures of the Mother-and-Child. Fuller did not go into the gendering of the genre, on which Luce Irigaray remarks in her call to put images of the Mother-Daughter couple in public places.xii If I seem to go wide of the issue here it is because, to me, the histories of art in public places, especially those in which commissioning agencies such as PADT and PACA were operative, seldom took on these deeper cultural issues. Yet, if art is to contribute towards any kind of public sphere, to do address such issues critically is vital.

A plethora of terms introduced to redefine public art since the 1980s - site specific sculpture, new genre public art, art in the public interest, and socially engaged art practice - have not clarified how the work of artists, or cultural producers, generates new public discourses. All too often it is the art institution's attitude which prevails. A default view may be that art in public places is simply the outcome of a succession of funding regimes designed to bring culture to a mass public (hence a public deemed by those responsible for the nation's taste to lack culture). Today, the debate is overtaken by new channels of web-based communication and by social networking (the democratic credentials of which are enhanced by using open-source software). But, to conclude, if my first reflection is that the exhibition encapsulates public art in cultural history, and the material seems quaint now - typed letters, hand-drawn images, before the days of e mail and the DVD - the questions, and the underlying social needs and injustices the projects might or not have addressed, have not gone away.

Malcolm Miles <M.F.Miles AT plymouth.ac.uk> is Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of Plymouth, and author of Urban Utopias (2008) and Cities & Cultures (2007)

Info

‘Art in Public Places: the Archive of the Public Art Development Trust' at the Henry Moore Institute , Leeds runsfrom 30 May-30 August, 2009,

Footnotes

i The idea of altermodernism advanced by Nicolas Bourriaud appears as replacement for the postmodernism he aligns with ‘a petrified kind of time advancing in loops' (‘Altermodernism', in catalogue Altermodernism Tate Triennial, London, Tate Publishing, 2009, p.13).

ii Stephen Feeke, gallery discussion, Henry Moore Institute, 1 July 2009 [transcribed from notes taken at the time].

iii Esther Leslie, ‘Tate Modern: A Year of Sweet Success', Radical Philosophy, 109, pp2-5, 2001.

iv artist‘s quote in ‘Art in Public Places: the archive of the PADT', exhibition catalogue, Leeds, Henry Moore Institute, 2009, p. 19.

v Sergiusz Michalski, Public Monuments: Art in political bondage 1870-1997, London, Reaktion, 1998, Ch.1.

vi Michael Sandle, from press release, The Independent, May 1987, cited in ‘Art in Public Places' catalogue, 2009, p. 4.

vii Malcolm Miles, ‘Aesthetics in a Time of Emergency', Third Text, vol. 23, 4, pp. 405-417, July 2009 for references to these and other groups.

viii Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and communication in modern art, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004, pp. 97-111.

ix Tessa Jowell, from statement at an event organised at the Royal Opera House, London by the Institute of Public policy Research, 7 March, 2005, in Engage, 17, p. 6, 2005.

x Clement Greenberg, ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch' [1939], in Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1986, pp. 5-22.

xi D W Winnicott, Home is Where We Start From: Essay by a psychoanalyst, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1986.

xii Luce Irigaray, ‘A Chance to Live', in Thinking the Difference: For a peaceful revolution, London, Athlone, 1994, pp. 3-36.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com