Agribusiness Invades Poland

Poland's recent membership to the EU spells catastrophe for its farming traditions, farm labourers and environment. Zoë Young reports

‘I’m not sure we can survive the European Union’, says Andrzej Konkol, an organic farmer in Kashubia, Northern Poland. His daughter translates while her young twin brothers amble about the yard in the afternoon sun, grinning broadly as they half lead, half follow a gangling calf. ‘When I went there, to Denmark, I saw only big farms. And I learnt that small farms like ours had all gone bankrupt.’

At the gates, a stork has made its nest atop a telegraph pole. On 40 hectares, Andrzej and his wife Teresa grow vegetables, cereal and fruit and keep pigs, cows, bees, dogs and cats. Children run, teenagers lurk and their grandmother feeds the chickens. Birds dart from wooden barn doorways to feast on insects over ponds, meadows and woods where black cranes nest and wild boar roam. Teresa does the milking, her mother in law makes butter in the kitchen, Andrzej cuts wildflower hay and tends pumpkin plants sprouting in pigshit compost. They heat their house with wood, and pickle vegetables for the winter. Nearby, Teresa’s father ploughs his steeper land with horses. But this is no medieval throwback – the family have two cars, a tractor and television, subsidies for their organic produce and, behind the garage, an eco-tourist campsite.

Poland is a country in between. Its 40 million inhabitants, over a quarter of whom were employed in agriculture in 1999, lie between East and West, tradition and modernity, communism and capitalism, Europe and the US. With the Polish government supporting Bush with troops in Iraq, in June 2003 nearly 80 percent of a 60 percent referendum turnout said yes to joining the EU.

The vote was ‘a triumph of urban Poland over rural Poland’, said the Times: text messages went to every mobile phone in the country urging people to vote. Museums even offered free admission to encourage city dwellers to stay and vote – rather than spending a weekend in the country, where the EU is viewed with more suspicion.

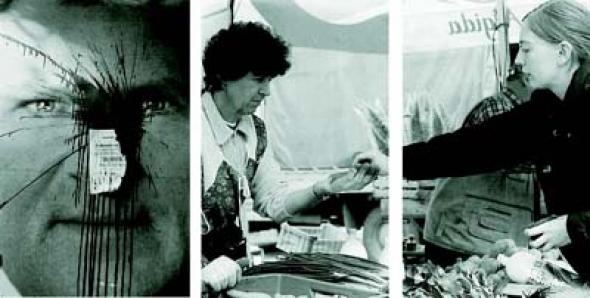

Unlike most benighted farmers in the UK for instance, two million Polish farmers still produce and deliver fresh food direct to local markets. With open borders to the EU, this example combined with wholesome exports from a land little touched by modern chemicals could be just what the doctor ordered for a Europe over-stuffed with factory farms, supermarkets and junk food. But instead of encouraging Poland’s comparative advantage in growing markets for traditional and organic production, many EU rules and regulations will be impossible for small producers and sellers to meet. Of course, some are in need of modernisation, and most Poles favour learning from other countries. But EU agricultural policies tend to subsidise large scale agribusiness at the expense of wildlife, food quality, local economies and the crop variety needed for food security in changing climatic conditions.

Polish farmers are vocal politically in their nascent democracy, and after centuries of resisting invasion and then collectivisation, opposed the deal their government struck for EU membership. But Poland also has one of Europe’s more corrupt governments, and despite widespread protest, with the help of multilateral banks, the agribusiness invasion is already underway.

Faced with a string of environmental and labour lawsuits at home, one US corporation in particular has been taking over Polish slaughterhouses and breaking veterinary and building law to turn former collective farms into ‘concentration camps’ for thousands upon thousands of pigs. Smithfield and its subsidiaries pump the animals with food and antibiotics, wash shit into lagoons and dump corpses that don’t make it to supermarket as pork. The goal, it seems, is to enclose, vertically integrate and profit from Poland’s productivity before a flood of Western European corporations come and do it their way.

Big British and Danish farmers are among those buying up Polish farmland to take advantage of lower production costs and the subsidy structure expected with EU accession. And as organic farm activist Sir Julian Rose laments: ‘The EU takes the view that drastic restructuring will be essential if Polish farming and the rural economy are to come into line with Western European standards and incomes. …[it] will involve stripping about 1,200,000 farmers of their land.’

With next to no subsidy to adapt, where should dispossessed farming communities go? To the cities, already with near 20 percent unemployment? To join the thousands of Eastern Europeans already working unprotected and underpaid in the EU as agricultural pickers and packers?

CEE Bankwatch and Green Federation Gaja campaign against the corporate invasion of eastern European agriculture. Support from abroad can make all the difference.

Bankwatch on Animex/Smithfield in Poland[http://www.bankwatch.org/issues/ebrd/animex/manimex.html ]Contact Robert Cyglicki + 48 91 489 42 32, <robertc@gajanet.pl >

International Coalition to protect the Polish countryside[http://www.icppc.pl/eng/index.php ]

Zoe Young <zoe AT esemplastic.net > is a researcher, writer, andfilm-maker with Conscious Cinema. Her book A New GreenOrder? The World Bank and the Politics of the Global Environment Facility, was published by Pluto Press in October 2002, see[http://www.newgreenorder.info ]

Picture Credits

Defaced poster of President Miler; Woman selling gherkins at a market in Wrzeszck, Gdansk. This practice will be outlawed under EU rules; Pigs on an Organic farm, Poland; Gherkin seller

Andrzej Konkol with his composting pig muck

Turnip stall at a market in Wrzeszck, Gdansk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com