404 File Not Found

Digital preservation is a growing problem but, asks Simon Ford, can we expect government agencies to deal with something so intractable?

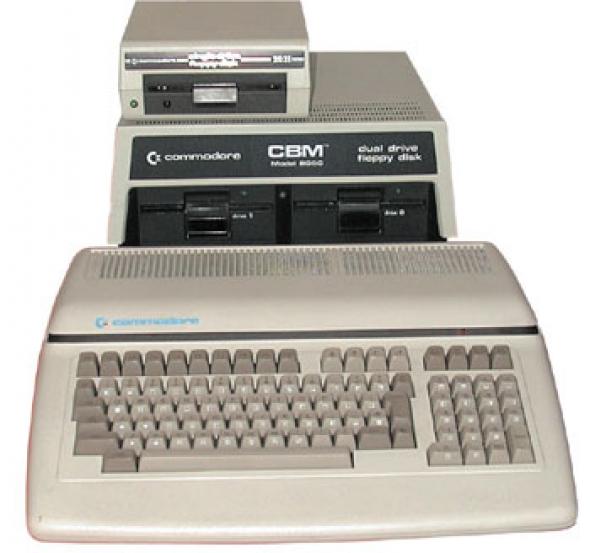

At the end of March we were invited ‘through the key-hole’ into Loyd Grossman’s brain as he pondered the volatility of digital culture. Holding up a videodisc made for the long-obsolete BBC Acorn computer he announced to the world: ‘The information on this incredible historical object will soon disappear forever.’ Grossman was speaking as the Chairman of the Campaign for Museums, a key member of the DPC (Digital Preservation Coalition), which also includes heavy-weight public bodies such as the Public Record Office, the Joint Information Systems Committee of the Higher and Further Education Funding Councils, and the British Library. The DPC was attempting to highlight the fragile nature of our digital heritage and lobby for resources to fund digital preservation projects.

Conservation and preservation are complex subjects at the best of times. Technical and ethical issues already abound, but take these fields into the digital realm, and digital art in particular, and things get even trickier. Art complicates matters because concepts of authenticity and originality require the preservation of both form (the hardware) and content (the code of its software and the files it draws on). In other fields literary historians gasp in horror as authors’ emails are deleted and PhD supervisors everywhere scratch their head as they mark dissertations containing web addresses for pages that no longer exist. Now it’s the turn of art historians to start worrying.

Existing strategies for preserving digital resources take the form of refreshing, migration and emulation. Refreshing involves the transferral of information to a ‘contemporary’ medium. Migration typically involves the journey of a file through a variety of software packages until it settles, albeit briefly, in another ‘contemporary’ package. Emulation works through software that mimics earlier applications (like the Spectrum ZX emulators available though Emuunlim). Hardware problems are more intractable. For example, with cathode-ray tube screens rapidly being replaced by flat-panel display units, how will future viewers recreate the conditions under which works were originally composed and viewed?

The size of the problem is immense. Taking the ‘.uk’ domain as an example there already exist about 25 million pages and with 60,000 domain names being registered each month the problem just gets bigger. Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately, the lifetime of many of these pages is measured in months rather than years. Not surprisingly the most common search result on the web is ‘404 File Not Found’. Some information, however, once released, has a habit of replicating itself. After September 11 federal agents in the US were quick to delete pages of information from government websites that could be useful to their enemies. Just as they were congratulating themselves it was pointed out that earlier versions of their sites, still containing the information, could be easily retrieved from the Wayback Machine, an archive of websites.

The anxieties raised by the DPC stem from our living through a period of transition between modes of historiography. Archives are disciplinary institutions in the mould of the prisons, hospitals and schools described by Michel Foucault and as such belong to the modern period rather than the postmodern – to the culture of the book rather than the network. The centripetal movement of an all-consuming archive is currently being replaced by a centrifugal force dispersing knowledge throughout networks. As such, archival efforts by bodies such as the DPC are doomed to failure or at best act as merely symbolic and futile gestures. Information will remain volatile, its circulation and mutation its only guarantee.

Digital Preservation Coalition[http://www.jisc.ac.uk/dner/preservation/prescoalition.html]Emuunlim [http://www.emuunlim.com]Wayback Machine [http://www.archive.org]

Simon Ford <sford AT metamute.com> is assistant editor of Mute magazine, author of Wreckers of Civilization and editor of Information Sources in Art, Art History and Design

Photo >> taken from [http://www.von-bassewitz.de]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com