Coloured Shadows

Coloured Shadows on the Wall

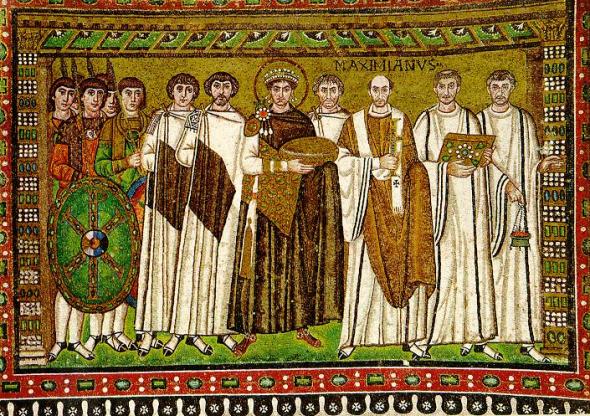

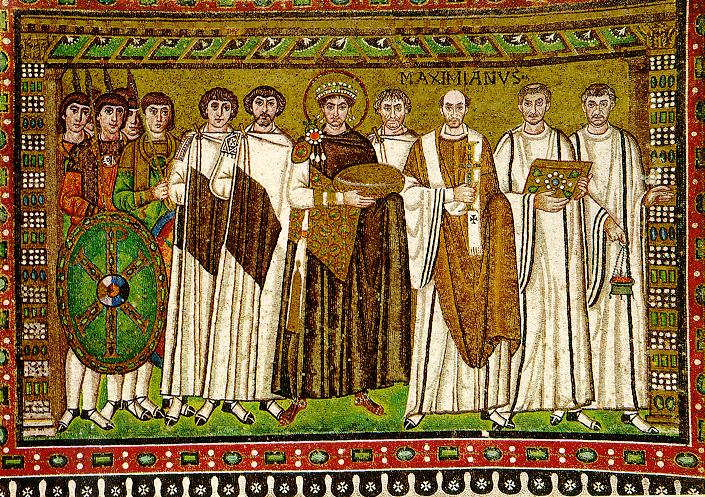

During the Middle Ages, having your image appear in a mosaic was a visible sign of one’s social rank. The creation of a mosaic was a task that required resources far exceeding those needed to produce a modern day motion picture. A mosaic created a long-lasting (albeit static) visual impact, creating fame and recognition for the individuals depicted therein.

A mosaic was, in most cases, created inside a church. There was no television so appearing on the wall of a house of worship was a big deal. Common worshipers and social elites would see those faces every time they entered the church, as would their children and grandchildren. Needless to say, casting for these “roles” was serious business. If you could get your face on that wall it was the closest thing to immortality one could hope for at the time.

Creating a Framework

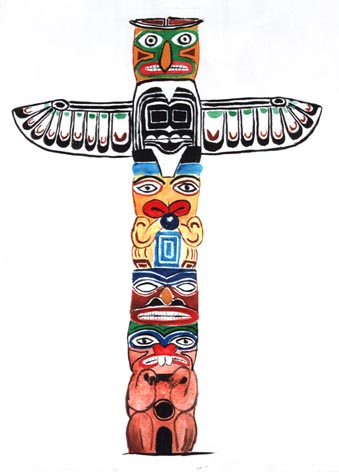

There were rules. The “star” of almost every mosaic was of course, Jesus. He would be located at the highest point in the arrangement. He was either with the gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), alone, or with some sheep (symbolizing his Christian flock). Thus began the hierarchy below which the “social scene” would congregate. The closer you were in the picture to Jesus, the more important you were in real life. The next one in totemic order was the emperor and after him came the Pope. Both the emperor and the Pope would be surrounded by their respective retinues, some nobles, a few generals and, at the very bottom, would be the saints (ironic how those with the most laudable traits always wind up at the bottom). Women were seldom depicted.

In the provinces there was more leeway. Series B gentry and social climbers could get their faces painted on the bodies of saints and apostles by commissioning the mosaic, whereas in the major cities only major heavyweights would be allowed in the picture. It’s a bit like the difference between appearing on local public access versus national TV.

At a time when there were also no print media (what use would it have been as most people were illiterate), painting in churches was the only way some people would ever “see” their rulers’ faces. This suited the rulers just fine; imagine how easy it was to keep one’s immutable image completely pristine while it remained cemented to a wall. This is precisely why numerous Popes and emperors invested so heavily in the creation of a ubiquitous visual presence: it generated immense returns. People admired and obeyed these stationary images on the wall and aspired to be like them. But whosoever acted in a way unbefitting their icon had to be “written out” of the story. It was a demanding role to play; once your character was drawn there was no editing the script.

A Strong Foundation

Fast forward a few centuries. Television has taken the place of the mosaic. The moving pixels have replaced the stationary mosaic tiles but the residual framework is the same. If you were in a mosaic a thousand years ago, you were considered to be an important and wise figure, someone to be revered (despite the fact that your image didn’t speak). Over time these images got cemented into the viewers’ brains. Likewise, anyone appearing on TV in Italy today is automatically famous and revered regardless of what they say (it’s as if the ancient walls are finally speaking).

Enter Gandini

Videocracy is Erik Gandini’s attempt to explore Italy’s complex relationship with the television for an external audience to see. During an interview with the head of one of Berlusconi’s networks, we hear that we can “get know Berlusconi and his vision of the perfect world by analysing his television programmes”, and this is exactly what Gandini sets out to do.

In the opening scene we meet a factory worker named Ricky. Ricky dreams of being on TV precisely because he believes that a TV appearance will help him to achieve a certain type of immortality. He believes that fame, riches and women will literally rain down upon him if he can just get on TV, and he tries everything to do so.

The images that Ricky and every other person in Italy see on TV are mostly created by Lele Mora, a close friend of Berlusconi. Lele sculpts and refines any raw talent he finds into “perfect” personalities for the various TV programmes and specials airing on Berlusconi’s networks. Lele creates the icons that Ricky and many other people worship so pathetically.

What are these images that everyone worships? The usual parade of scantily clad silent swimsuit ladies and Ferrari driving male underwear models that do nothing other than make the viewer feel inadequate and useless – what’s so new about that? What is new about it is there is nothing else anymore. In the 60’s and early 70’s, the poet Pier Paolo Pasolini was inspired to enter the film industry because he claimed that Italian TV was showing a world that didn’t correspond whatsoever to reality, and now Gandini is showing us an Italy that is mimicking that same phantasmagorical television world.

Young girls line up for degrading competitions in the hope of standing next to a presenter on TV. They are not allowed to talk. Men like Ricky spend all their time and money trying to become a personality “fit for broadcast”. While all the personalities that do get any serious TV exposure must first be groomed and moulded by Lele, who, in his own words says that “Berlusconi is a great man, but nowhere near as great as Mussolini”. Needless to say, Lele must be a difficult man to impress.Paying for Perfection

The same hierarchy from the mosaic still exists in Italy; whoever is closest to Berlusconi is most important. Berlusconi is the closest thing to perfection that anyone can see on TV. The closest thing because, as the saying goes, “no one is perfect”. At least not in real life, but according to the bible there was once a perfect being. A perfect being from whom all personality was drained. His name was Satan and he resides in Dante’s 9th ring of hell; the central ring.

Perhaps Dante’s inferno wasn’t actually a description of hell, but rather an indictment of the social hierarchies that keep people confined to one ring or – even worse – to one role. If you read The Inferno, you will see that it mostly discusses the iniquities of people who had not acted in accordance with their role. Being bolted into one static role seems, to me at least, like hell. Never having the option to do something different or try something new or stand up for what you believe in because doing so would shatter your predefined image.

Much like the emperors who drained conquered lands of their wealth to create their own world, Berlusconi is sucking the personality out of Italy to make a perfect TV land where every real Italian becomes a stand-in for reality.

The Corona Phenomena

Fabrizio Corona is another principle character in Gandini’s film. Corona runs the entire gamut of the show business world in Italy. Formerly an assistant to Lele, he left that hallowed position to become a celebrity photographer. He doesn’t actually hold the camera; he tells a crew of paparazzi where to go to find the celebrities. When he gets incriminating shots of the celebs, he calls their publicity agents to sell them instead of going to the newspapers. Fabrizio gets famous for this and becomes a TV celebrity himself. People line up to take their picture with him even though he is on trial for his blackmailing activities. He says things like “This entire country is rotten, the people are rotten” while kids keep lining up to take their picture with him. It really doesn’t matter what you say, as long as you are on TV people want to be close to you, to taste your fame. Maybe they will never be on that mosaic, but taking a picture with someone who was is the next best thing.

Eventually Fabrizio goes overboard with his self promotion and tries to get the father of a murdered child to wear a Corona T-shirt at the highly televised funeral. When Lele hears of this he wants Fabrizio erased from the picture and eventually Fabrizio slips into obscurity, leaving nothing but his blog (with an Alexa traffic ranking of 792,229) behind him.

Keeping Up With The Flintstones

Part of the reason why mosaics from the Middle Ages were so powerful was due to the high level of illiteracy in Europe at the time. Images were more powerful than any words some “heretic” like the 16th century Italian monk, Giordano Bruno could produce from the fringes of society. Bruno was burned at the stake by the Pope because of his independent mind. He was the first to conceptualize the universe as we know it today, but he made the mistake of writing it down. Who could understand him if no one could read and they all spoke different dialects? He should have drawn a picture instead. (Similarly in Colonial America, slaves from different tribes were intentionally mixed together to prevent them from revolting or even communicating).

Despite the fact that almost everyone in Italy today can read, 80% of people get their news from TV while the Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi owns most of the channels. Much like the previous emperors, Berlusconi is very comfortable with the low level of media-illiteracy in the country because that way no one can see through his near-perfect facade. There are no Dantes to strip away the celluloid veneer, nor are there any Brunos to illuminate the black hole that is passing for a universe on TV. Berlusconi’s projection is infinite, ageless and boundless; the only thing better than having your subjects speaking different languages, is to have them all seeing the same identical image.

You See What You Know, and You Know What You See

In his Theory of Practice, Pierre Bourdieu wrote that “The mental structures which construct the world of objects are constructed in the practise of a world of objects constructed according to the same structures.” Thereby the people learning to make objects while they grow-up surrounded by such objects will inevitably construct similar objects. But I think this can also be applied to visual constructs and not just material ones. People build schemas based on the information available to them, and the less information you have, the broader your schemas. Schemas used to be a good thing in the Middle Ages; they would protect you from marauding barbarians. But whereas in the Middle Ages such prejudices would keep you safe and secluded in your cold stone home, nowadays they just leave you alone in the dark, outside and freezing.

Berlusconi has created nothing new in media. He and Lele Mora have simply regurgitated the same anachronistic television they grew up with. Television that was completely different from the reality outside. Television that perpetuated the same banal schemas we have seen for centuries, television that objectified women and idealized men, television that said everything is fine… television that Pasolini rejected.

Bourdieu goes on to say that, “The mind is a metaphor of the world of objects which is itself but an endless circle of mutually reflecting metaphors”. For Berlusconi, women are treated as objects, and these objects only come into existence once they appear on TV. All those young girls were going through that degrading veline competition just to be reified.

A Happy Ending: Towards Superlanguage

There is a happy ending to all this. Media-literacy is on the rise worldwide and hopefully this will reverse the balance of power in countries like Italy. Pierre Levy coined the term Superlanguage which refers to a new level of communication that will be capable when the collective intelligence of humanity can even out the flows of information.

According to Levy, the transition from telephone to broadcast to cyberspace shows that we have progressed from a “one-to one” to a “one-to-many” to a “many-to-many” mode of technological communication. Right now it would appear that Italy is at the “one-to-many” stage of this process, but I predict that within a generation or two people will be communicating in a Superlanguage consisting of all media (text, video, photo, etc.) and which the ruling classes will have difficulty emulating or even understanding. The upside of this theory is that it will be a language for everybody, with no one group being more literate than another!

For now, Italians can at least enjoy one benefit of the current situation. Whereas Italians in the past had to hear shouts of “pasta, mandolino, mafia” while travelling abroad, at least now they can save time by having all these stigmas merged into one globalized schema: Berlusconi.

–Jeffrey Andreoni

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com