No More Poodles II: Bogue versus Vogue

In the second installment of his music column, Ben Watson wages a war of social being against the hip priests of consensus reality

Just what it is that makes things vogue? When you're young and ignorant, vogue is all you're offered, and you perforce make do with that - until you've burrowed your own way into that festering midden called culture. A select few among the older and more knowledgeable finally gain the power to make vogues, or at least to jump on Zeitgeists which seem mysteriously to arrive from nowhere. What's vogue must titillate with the unknown and pullulate with danger, though it must also confirm existing institutions and flatter acknowledged expertise. So I'd cite as ‘vogue' the John Latham revival, which has everyone from David Toop to Stewart Home and Lol Coxhill and Ulli Freer ‘celebrating' the work of the artist who burned books back in the '60s. What's the opposite of vogue? What I like, which I'll call bogue. Bogue is casting off precedent, and doing what you have to. As I put it in an episode of Late Lunch With Out To Lunch called ‘Output' (Resonance FM, 8 December 2009): ‘Pertinent art is the necessary output of a particular set-up, not some arbitrary clown drawn on black velvet with a great swanky signature beneath'. This could serve as a manifesto of bogue. What made punk fantastic was that its bouleversement of value made everyone face with sober senses what the entertainment industry was actually giving us; its theoretical inputs were put to work, not worn as badges of cool.

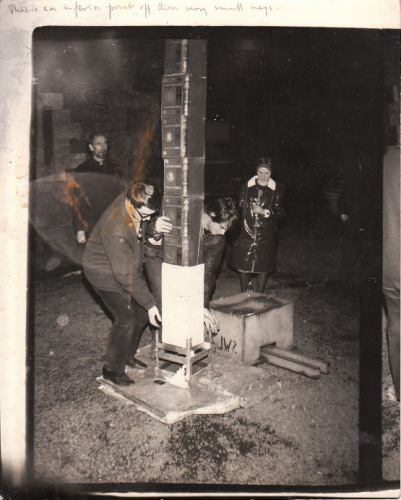

Image: John Latham, Skoob Tower, 1964

Ambient and electronica are last year's news, so now the spotlight of vogue falls on nihilism and noise. ‘Classic' artworks are salvaged from attics unvisited since the '60s and presented like Greek statues dredged from the Adriatic, untouchably violent, beautiful and extreme. The objects of admiration may have changed, but really it's just another collection of dodgy haberdashery swishing down the catwalk. We're asked to admire, but not challenged to speak ourselves. The same names are still in charge, the same faces review the parade from their well-protected balcony. As against the vogue, the bogue follows Lenin's definition of dialectics (1915): it splits the whole, causing the question ‘sublimity or trash?' to rise like the shadow of a monstrous crow's wing over the auditorium, forcing passive spectators to take sides, to articulate their responses, reveal their interests, their intentions, their social being and hitherto unsputtered politics. Where there's no longer any doubt about the value of an artwork, it's stone dead - pointless, stopped working, become part of the furniture, the legacy. Capital.

If nihilism has been recuperated, and the dial-a-hip-track wannabes and eavesdroppers are purchasing Latham prints and swapping Fluxus-outrage anecdotes at Café Oto and hiding their Brian Eno albums behind racks of Keiji Haino and Mattin CDs, where can true rebellion and principled critique be found? The stock response, injected into every humanities graduate in capsules of post-68 French philosophy, is that recuperation is inevitable, so it's naïve (‘undertheorised') to expect anything else. But the bogue can't submit to such polite platitudes, its defining characteristic is complete and ingrained independence to official public opinion at all times and under all conditions. The bogue's got to have a last laugh, it won't give up the fight. It's going to wade right into the muddy waterbed and find the living rivulet, the pure stream, the twinkling that brooks no end. The current vogue for nihilism opens up a '60s scene riven with faction and debate, where beauty and nonsense and brute media power flash past each other in quick succession. To gain our bearings, we need to resort to the only compass left with maps all aflame: our own aesthetic responses to the stuff left behind. This ‘subjective', ‘unproveable' taxonomy is anathema to cultural pundits who, seeking stipends as official astronomers and fixing their telescopes firmly on the past, hypostatise success and visibility into something as eternal as the stars. If you can find a connection to Pink Floyd, it's like finding documents which prove you've got royal blood: money in the bank. Albeit taxed from fools and voyeurs and gawpers. But to the bogue, Pink Floyd were rubbish, posturing unmusical scenesters, and, besides, all bygones are bygones: what we want is events now which can prove we're still alive. The pseudo-objectivity of the cultural pundit is just a mask for working for The Man, man.

The point is that John Latham's burned-book paintings look stupid and vile. Overdetermined and underworked, like music by Cornelius Cardew (another saint with wobbly feet you're not allowed to knock). They're stunts, not artworks. At least the Fluxus deposits at Tate Modern have the grace to look like mere remains, dry and pointless (even if they fail to live up to Fluxus' amazing talent for self-promotion). Latham's works are gawdy, grandiose and utterly vacant. The book is dead? Everyone and Marshall McLuhan's aunt were announcing that at the time. In fact, Latham is so downright bad he makes Diether Roth look like Kurt Schwitters. But, of course, error isn't a primal force, just truth deflected, so maybe wrath should give way to pity. In 1974, when David Toop signed a letter with John Latham and Marie Yates to The Guardian announcing as otiose the categories of poet, painter and composer, they did have a point, although they were making it about fifty years too late. In the epoch of the commodity, cultural ‘expertise' all resolves to one issue: use value or exchange value, something for me, or for the aggrandisement of capital? There is no poetry, no painting, no music: just the problem of the commodity and what we can do about it.

Still, however much it represses real aesthetic discussion, at least the John Latham revival brings back the revolutionary moment in the late '60s when James Joyce's Finnegans Wake was recognised as the epochal work of subversion it is: the everyperson's Bible of post-capitalist demotic self-psychoanalysis und Jedermann sein eigener Pun-Meister; the organised and sensual elevation of book-reading into supersensitivity to the mediatised actuality of the modern metropolis and cyberspace. An outline for the correct relation of individual oral-manual spontaneity to multi-tongued internationalism and electrified instantaneousness! After the Wake, all must be reassessed afresh in the light of our needs and desires. Now, this is a programme worth fighting for!

But if all this is true, reviving an artist because Pink Floyd once nearly wrote a track named after him (Nick Mason ‘can't remember' according to David Toop's article, Wire #317) is hardly enough. Why should we be content with the paltry figureheads and dozy intellects tossed up by profit generation in the past? Why should we be content that editors who refused to run a major interview with Bob Cobbing in his lifetime are trumpeting his virtues now that he's dead? Why should we be content with business as usual? It's common knowledge - a lesson imparted to tens of thousands of Eng Lit. and Art History students - that the William Blakes and Van Goghs and Nick Drakes are only recognised once they're dead, their active opposition to the powers-that-be silenced. But to watch this happening in your own lifetime is chilling. For years Bob Cobbing held a weekly gathering in pubs - Writer's Forums - which anyone could attend. Those that did now write the good stuff. Do we hear about them now that Cobbing has become a great dead artist to fantasise about? No.

The word everyone's groping for in dealing with Latham is there in Guy Debord, it's bourgeois. The ‘nihilism' of the '60s had a target, the liberal culture developed by a particular class in Europe over the 18th and 19th centuries. It was this genteel culture of exclusion and taste and difference which Joyce and Varèse and Coltrane and Hendrix trashed, proposing new artistic vibes which could twang the proletarian body directly, bypassing the literary cultures curated by national bourgeoisies. That's why the word had to burn! Without this political thrust, everything dwindles into the mystic gothickry of a Coil interview. There are words to deal with the wreck the '60s made of liberal culture, but they can only be supplied by a revolutionary Marxism which marketeers and petit-capitalists choke on. Each true artwork today tests your mettle as an individual, asking if you can explain the crap that's flying at you: no amount of ‘avant' homework can prepare you for the shock. The difference between those suckered by the thespian posturings of Keiji Haino and those who can hear the unlimited freedoms of Masayuki Takayanagi is so vast, these listeners are not in the same place. At least, not socially. It's not a ‘musical' debate, it's a war of social being, of religion. We're dealing with the clash of epochs here, comrade, class struggle! Without such terms you cannot understand it.

Image: Jimi Hendrix in Montagu Place, London by David Magnus,1967

‘Where are your '60s now, though?' retort the marketeers, their vision utterly occluded by the megabucks earned by The Beatles. In today's uneasy mix of cultural regression and frustrated revolt, there's plenty of room for murk, but what Latham said in his letter to The Guardian still stands: the division of cultural production into ‘literature', ‘music' and ‘art' is utterly meaningless. Prepostmodern if not simply preposterous. Finnegans Wake reconfigured the printed page into music - not that of Richard Wagner, although he provides a kind of basis for the book, a sound poem Book of Kells improvised as a Ring Cycle parody. According to Bob Dobbs (www.fivebodied.com), the Wake is ‘rock'n'roll in print', and the reason Rolling Stone couldn't guage the music was that its writers didn't read Joyce, holding onto a Harvard mindset moulded by Nathanial Hawthorne. No wonder they lauded Bob Dylan and insulted Frank Zappa: they were looking for lyrics in fine print rather than someone who could manipulate the electronic storm and bring enlightement to bear. And no wonder Rolling Stone made a superstar of a musical zero like Bruce Springsteen.

Literature was the creation of the bourgeois class, and retains the imprint of its privilege and topdown purview. In an epoch of mass production, singleton artworks can only be a paradoxical enterprise: Marcel Duchamp diagnosed this correctly, even if his clever diagnosis becomes paler and more tedious with each repetition. Massaging the body directly, mass-disseminated music answers William Blake's demand that we open the gates of the heart, the loins and seminal vessels, the stomach and intestines, as well as the abstract spaces of the head (Milton, 1804, plate 34). René Descartes was wrong: the location of the soul in modern man is not the pineal gland, it's music. In Blake's time, what raised the temperature of discussion in the coffee house was the divine nature of humanity after Jesus; what raises it now - because Marvin Gaye and John Coltrane do materially transform their listeners into angels - is anyone voicing an honest reaction to the music they hear. Music is where the pressures of global capitalism impinge directly on the human animal, wreaking changes his or her conscious mind must catch up with, or perish as a living soul. To talk about it is to foment revolution.

But, just as Rolling Stone writers went astray because their models of linguistic precision were outdated and parochial, so today our dedicated musical experts betray this modern soul if they don't keep up with technical developments in literature. Hence the relevance of Bob Cobbing, Iain Sinclair and J.H. Prynne to anyone trying to register the impact of musical excitements using words. Sensitivity to the visceral, musical impact of words - the oral, intent-driven gesture of every remark, its active weight as social utterance - is required, or the writer walls out the corporeal evidence of their senses five in favour of ideology, morals, feminism, eco-politics: the usual sorry piffle which replaced the classic outpourings of the counter-culture (Oz, International Times, Suck, Crawdaddy!, Impetus, Hawaiian Picnic etc.). Music magazines will only make sense again if they - Bananafish-style - also become capable of reviewing bus-stop layouts, poetry pamphlets, readymeals, squat parties, Primark bargains and Waterloo sunsets. Iain Sinclair reinvented the book by writing about streetside London as if he was reviewing art installations. Latham and his like threatened to bring into art the world outside the gallery, Sinclair took them at their word, and began reviewing the contents of skips, the Millenial Dome, a charity shop on Stroud Green Road. Properly alerted to the pros and cons of the commodity, the music writer should be able to review anything, and should make a better job than the pundits and experts of separation. Great writing occurs when the occasion is properly askew, and the grisly routine of info or puff (or defence of the status quo by mild putdown) is dislocated, and there is a genuine vibe between writing subject and cultural object, as when Ed Baxter reviewed a CD of Margaret Thatcher's speeches as an avant-garde release. Love or hate are worth reading, everything else is worthless, especially slavish responses to what's vogue.

So what's bogue today in the music field? The latest poetry release by J.H. Prynne, of course! Having shaken himself out of the honeyed Heideggerian daydream that was The White Stones with the Tzaratic ziggurat of Brass (1971), Prynne joined the select band of trashcan writers: poets who have binned the middle class presumption that the poet is an ethical font, and instead presents a brewed compôte of immiscerated materials which refuse identity thinking. Working on a stretched syntax with increasingly brain-popping contrasts of lingusitic sourcing, Prynne's poetry is the first step beyond the Wake for a discourse capable of dealing with contemporary semiosis and the dazzling phoneme-reaming of dancehall DJs and hip-hop rappers. As critic Michael H. Tencer put it, on hearing Keston Sutherland's assertion that Prynne is the most important British poet since Wordsworth: ‘I thought he was the best thing since Captain Beefheart!'. Issued on Barque, the label Sutherland runs with poet Andrea Brady, Prynne's newie is Sub Songs, and it's huge, at least in terms of physical size. It's bigger than Brass, it's dark blue and floppy and shiny, and it handles like a special edition for the visually impaired. Gone is the tight, hard-pruned layout of previous pamphlets To Pollen (2006) and Streak~~~Willing~~~Entourage Artesian (2009). Visually, Sub Songs recalls the discursive sprawl of Brass. But the rate of semantic rotation applied within each sentence is far faster, like going from the saxophone phrasing of Lee Konitz to John Butcher, a relentless punching that leaves you breathless: ‘Say fable live fine table set, pro net bash your/head fond grind momently for bind tame shellac roller/trangress disgust or bitten hit, what no matter is/compelled to pacify.' (‘As Mouth Blindness'). What vowel leaps for your hot lips to hop! Whereas Finnegans Wake, with its relish for smut and nursery rhyme and lowdown Dublinese gutter repartee, taunted Rebecca West and the Bloomsbury highbrows, this packs the scorch and wrath of Blake and Wyndham Lewis, as they pan the hirelings for selling-out their art. It's like swishing the bubble bath and meeting a razor blade, the clinical slice within the fluent iridescence. Prynne hurts! Yet there's balm as well as blam, because awareness of the multi-application of each syllable gleams opalescent, stinging yellow-greens mixed in with sprinkled pinks and mauves like ‘grey' rocks sparkling in a Studio Ghibli animé.

Image: still from Ponyo, 2008, Studio Ghibli

Prynne's evasion of the cadential ‘decent' thought hosanna'ed in the classroom poets opens up energies beyond the current social-democratic fix: ‘unseeking nibs to thought and grief excess abusive wanted at fill/longer attract best choice get select or secret heart why bled/to beam sporadic all we know heroic play up to her simple blank/counted seldom, pure in here now is lower demise profile cut free/stay or part leave' (‘These Nothing Like'). As a re-consideration of the major motivational forces spurring Shakespeare's blank verse, Sub Songs bears comparison to Dr Who's current reformulation of Tudor theatrical plot. Like Takayanagi demolishing Japanese ‘jazz' in 1969, Prynne's ‘nihilism' wreaks black gashes which twinkle with new lights, ludic potential undreamed by Roger Scruton. Active dada in the interstices of the culture, where John Latham was too ham-fisted to push it. The linguistic music of Sub Songs - a dream of righteous epic after the Wake, after Burroughsing through sex, after the perils of auto-destructive art - deserves consideration by anyone trying to find words to describe the sensation of hearing The Beatles as a Superimposers covers band, or ‘You've Been Talking 'Bout Me, Baby' by Ray Terrace played late at night on Soho Green by the Karminsky Experience. In other words, crucial reading, pop pickers.

Ben Watson < info AT militantesthetix.co.uk > is a music writer (Frank Zappa: the Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play, Derek Bailey & the Story of Free Improvisation) who in 2005 decided to abandon his struggle with Wire magazine and raise children instead. He broadcasts a radio show ‘Late Lunch With Out To Lunch' at 2pm Wednesdays on www.resonancefm.com . You can hear past shows on www.archive.org, or send me an e-mail.

Info

J. H. Prynne, Sub Songs, Barque Press, 2010

Ben Watson's recitatation of Sub Songs, in its entirety, may be heard at www.archive.org/details/Epic12-v-2010

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com