Archive Trouble: Collecting and British Punk

Punks collecting things other than safety pins and STDs? Jon Bywater looks at the tendency among Punk enthusiasts to compile catalogues and measure their contents in this month's Mute Music Column

...the most distinguished trait of a collection will always be its transmissibility. You should know that in saying this I fully realize that my discussion of the mental climate of collecting will confirm many of you in your conviction that this passion is behind the times, in your distrust of the collector type. Nothing is further from my mind than to shake either your conviction or your distrust.

- Walter Benjamin: ‘Unpacking my Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,' 1931

Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.

- Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz, 1995

Published in 1982, B. George and Martha Defoe's International Discography of the New Wave is a staggering agglomeration of information about the published expressions of the punk moment and its aftermath worldwide. By post and by phone, it assembled alphabetical listings of ‘over 16000 records' by ‘over 7500 bands' as the back cover boasts, contact details for ‘over 3000 small labels' and ‘over 1300 fanzines', and pages of advice on contract and licensing negotiation, interspersed with collages of selected picture sleeves and Pam Meyer's distinctive graphic doodles. The photographs that form the background to its opening pages give a glimpse of the conditions of the production of this brick-like paperback: a desktop caked with boxes of index cards, coffee mugs, and an office pencil sharpener, someone doing manual layout on a drawing board under an anglepoise lamp, piles of LPs on the floor and racks of cassette tapes on the wall. Curtis Mayfield and the Harptones (featuring Willie Winfield) are visible at the front of the stacks and flyers for Scritti Politti and the New Age Steppers on the wall. What Nancy Breslow writes in her entry about fanzines as ‘a true underground network spanning the globe' rings true of the entire project's ethos: ‘we do it, we control it, and anyone can be part of it. This excitement continually astounds!'i

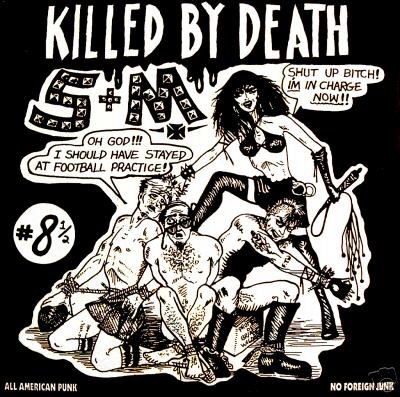

Image: 'Killed by Death' series cover

The book was at least ten years old when I first saw a copy, secondhand in Smith's Bookshop, Christchurch. I flipped through it and put it back. The magazines listed were defunct and the addresses had gone cold. The comprehensiveness of the discography seemed simply indiscriminate. A previous owner has underlined in red ballpoint the small percentage of the records she or he owned, a selection clearly overdetermined by forces outside personal judgement: major label bands, released here in New Zealand. The annotations' alignment with the phrase Forced Exposure magazine had popularised, ‘consensus reality', seemed faintly tragic. It can not have been long after this, though, that I kicked myself for missing the correlative interest in this book that others at the time were discovering. Just as the music of that period survives to be taken up in new (and not so new) ways, so too was the book. At about this time, it became re-evaluated by collectors as a tool with which to scour for unheralded gems of the era and consequently became a collector's item in itself, in connection to the buzz surrounding the uptake of the now ubiquitous genre term for raw and rare punk instigated by the bootleg compilation series Killed By Death (from 1989).ii

In the social world in which I came to know music – to know about knowing about music, one in which knowing about music is about differentiating oneself, making oneself someone; a white world of underground rock – I have heard the collector's position routinely disparaged. Perhaps it is to be too openly competitive in one's desire to accumulate, or contrary to the ease with which perfect sound forever should come, at risk of making the cultural capital appear arriviste? At any rate, while having a collection might be something admirable, there is conspicuous distrust of the collector type. Johan Kugelberg's ‘The Psycho-Geography of Record Fairs: Utrecht, WFMU and London Olympia' (February 2009) captures this ambivalence well, in its half-joking self-deprecation of his own passion (‘But I jest, just a little bit. A VG minus of jest.').iii It's a cheap shot with the force of truth: punk collecting, in particular, is an oxymoron. What could be further from the spirit of rebellion than shopping obsessively for the artifacts it left behind? Through the collector's market most conspicuously, the revitalised ideals of participation and make-do are commodified and ‘turned reactionary' (Kugelberg cites Guy Debord as his epigraph). In this light, the collector's identification with punk appears hypocritical, an antithetical and alienated form of luxury consumption.

Marco Panciera's 45 Revolutions: (1976 / 1979) Punk, Mod / Powerpop, New Wave, NWOBHM, Indie Singles in the Years of Anarchy, Chaos and Destruction, Volume 1: UK / Ireland (2007) descends from and resembles George and Defoe's Discography, but is motivated quite differently. Where George and Defoe and their networks of collaborators might have aimed to grow a living phenomenon, Panciera and his collaborators define their subject as something finalised. The work's deeply considered parameters – singles released by bands from Ireland and the UK, from the emergence of punk (defined as being from the month of October 1976, the date of the release of the Damned's ‘New Rose') to recordings made before the end of 1979 – express a collector's desire for and pleasure in the completion of a set. Within these carefully impersonal limits (a singular origin, nation states, calendar dates, the vinyl single etc.), it indeed offers a definitive index of punk's British and Irish publications.

In a self-financed labour of amateur scholarship, Panciera has worked on compiling this information for the last 20 years, with significant input from the most committed fans and collectors of this music, principally his ‘co-conspirator in chief' Steve Mitchell.iv Appearing when it did, it is in some respects a post-Internet document, comparable to other rock discographies that have benefited from distributed, informal collaborative input in the email era, such as Vernon Joynson's Fuzz Acid and Flowers Revisited: Comprehensive Guide to American Garage Psychedelic and Hippie Rock (1964-1975) (2005) and the incorporation of Ron Moore's Underground Sounds into Patrick Lundburg's The Acid Archives: A Guide to Underground Sounds 1965-1982 (2006). In this case, the telephone has probably been the primary research tool, though, used to track down and solicit information actively from band members. Combined with material from an exhaustive library of press clippings, the careers of the more than 2000 acts are detailed, and a photograph and an account of the recording and reception of every one of their 3000 odd singles is provided.

Walter Benjamin, famously himself a collector, suggested that ‘[e]ven though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter'.v This publication seems to bear out something like this, in that it's hard to imagine this work being achieved outside the sphere of the amateur, in the literal sense of one moved by love. As a private work made public, in some ways it achieves the best of both worlds. Benjamin's logic of social acceptability can be broadly generalised, of course. As James Clifford's classic analysis of the cultural politics of collecting notes, the fetishism of a collection is generally redeemed through being made public. In ‘good' collecting, ‘[a]ccumulation unfolds in a pedagogical, edifying manner.'vi How, though, might the value of 45 Revolutions as an expression of punk collecting be measured more precisely? If – to return to Benjamin's terms' '...the most distinguished trait of a collection will always be its transmissibility', what is here transmitted?vii

The introduction makes it clear that ‘philosophical and sociological digressions are outside the remit of this volume'.viii There are hints, though, that the authors' stated hostility to ‘long words' is an expression of contempt for premature or ill-informed analysis rather than any analysis. Offered in the context of the pithy discussion of inclusions and exclusions, the thesis that ‘there was clearly as much Glitter, Bowie and Roxy as Situationism, Breton and Tzara in Malcolm McClaren's vision of the Sex Pistols as "a raunchier Bay City Rollers"' is a wholly convincing riposte to Greil Marcus.ix For the most part, however, the implications of this archive for our understanding of the period and the phenomena it documents requires active interpretation. Benjamin again: ‘"The only exact knowledge there is," said Anatole France, "is the knowledge of the date of publication and the format of books." And indeed, if there is a counterpart to the confusion of a library, it is the order of its catalogue'.x The very plainness of the factual approach in this way helps to reveal the true complexity of its subject.

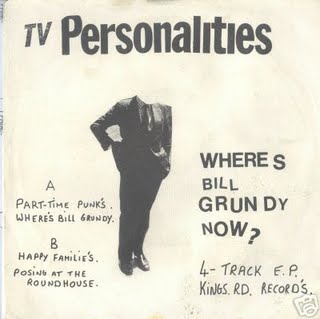

Throughout the book it becomes obvious that as early as 1978 punk as a fashionable mode was under suspicion from music critics. The Reducers entry, for example, includes the remark that ‘The single was praised by Record Mirror and the NME at a time when anything remotely Punk was automatically subject to a backlash.'xi Mass media and mass market distortions of value, of course, were the currency of punk's own social critique. The Television Personalities (whose name itself was intended ironically on this point) joke in the song ‘Part Time Punks' from their first, self-released, 1978 45:

Then they go to Rough Trade

To buy Siouxsie and the Banshees

They heard John Peel play it

Just the other night

They'd like to buy the O Level single

or ‘Read about Seymour'

But they're not pressed in red

So they buy The Lurkers instead

Through the accounts of the reception of each record, 45 Revolutions reveals in minute detail the mediated formation of the genre during the period, and the full picture of what people were making and doing will trouble any simplistic account. Relative to this overview, writers who theorise this era do sometimes seem to rely on a sense of history significantly shaped by sales and media attention. The book's exhaustive ambit, then, has implications for how British punk can best be understood from the primary evidence, the fanzines and records.

Image: 'Part-Time Punk's' cover

The snippets of contemporary reviews appended to most entries are often fascinating and occasionally hilarious. They reveal, for example, how something a reviewer was impatient with, for its amateurism or derivativeness (‘The vocals and theme are lost way back in ‘77' writes Robbi Millar in Sounds in ‘78) can become gold at this distance to listeners who want more of something they already know well, or who value the added lustre of budget recording and limited skill sets.xii The book's primary audience will be such collectors; hence occasional, unlikely imperatives like ‘Both stock and demo copies should be collected...'!xiii Even for such a specialist, the book can dispel the vague sense of there being an underground of unknown scale that supplements a (perhaps over familiar) mainstream; and so offers a finite set within which discriminations might be made.

Why would a non-collector care at all, though, about a record like Zoot Alors unsuccessful Decca demo, ‘Send Me a Postcard'? Kugelberg's allegory of the ‘hedge-fund lower- upper- management aging hardcore kid spending four figures on Misfits test-pressings' captures the idea that listening to such ‘old' music is to risk living in the past.xiv Trying to hang on to a vanished youth, this figure is guilty of a futile nostalgia in his attempt to connect with an illusory golden age. The capitalist-propelled modernist, progressivist sense of history – in which the ‘present' tends to shrink to the latest six-month season – is something to be suspicious of, too, however. The concept of the punk impulse to reclaim music as an activity, a social space between peers, even when it involves buying and selling, remains pointed under contemporary conditions. The distance in time of such musically conveyed attitudes from this recent past, and the supposed ‘naïevté' of their expression according to today's commonsense might provide us with distance on exactly those assumptions, and offer a difficulty more exacting than formal novelty. The music has uses beyond as well as in sympathy with the intentions behind its creation.

Another general force that would have us put this music aside is modernism's lingering demonisation of genre and idiom, its fantasy of getting beyond genre. The depth of the collector's passion for a specific area of music is at least suggestive of a rebuttal: any aesthetic judgement is relative to a field of experience, and so the pleasure and sense of possibility garnered from a fine grained comparison – understanding that this previously overlooked powerpop track is an impressive example of its kind – is not to be easily dismissed as inferior to one that is about a contrast of different orders; that this academic compositional strategy is so surprising to me that it refreshed my hope for a changed and better world, say. Beyond the usefulness of being surprised, pushed, and disoriented, too, there is in also a usefulness in the feeling of being held by the familiar, experiencing the skill of connoisseurship. More interestingly, both such uses relate to the creation of personal meaning and may in fact coexist.

Implicated in the formation of self or group, in collecting ‘[a]n excessive, sometimes even rapacious need to have is transformed into rule-governed meaningful desire.'xv Those rules, although they are often importantly formed around public categories, as Clifford notes, are at the very least interpreted individually. The impersonality of the book?s criteria for inclusion, as discussed above, represses and so points up that element of the collector?s psychological satisfaction that comes from making their own field within which to place individual songs. Thus the genres (such as those named in the book's subtitle: punk, mod / powerpop, new wave, NWOBHM, indie) can only go so far in describing, for example, the various styles that are manifested in the compilations of this music published at the peak output of bootlegs in the 1990s, including notably 'Bloodstains Across the UK' (four volumes 1996-1998), 'England Belongs To Me' (four volumes 1996-2000), 'Raw and Rare British Punk' (four volumes 1997-1998) and 'Teenage Treats' (ten volumes 1997-2000). Reflecting the proclivities of the (not always consistent, of course) compilers, they make it obvious that the aesthetic coherence of any combination of recordings from this period may be judged differently by different people.

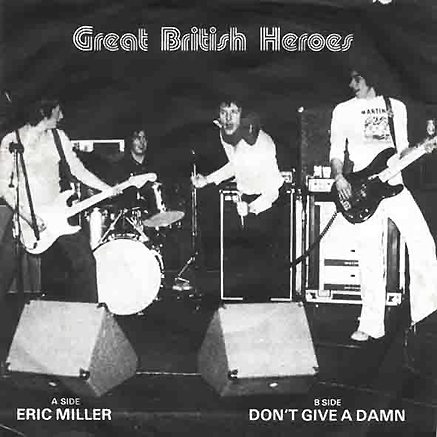

On the question of evaluation, 45 Revolutions' authors state that in their book ‘[o]pinions are kept to a minimum and are mostly expressed through quoted period reviews which, decades after the they were written, have themselves become historical artefacts.'xvi (In fact, I suspect, opinions are simply expressed in rather than through these reviews, the point being that they, as much as everything else, are open to interpretation.) Nonetheless, a prominent feature of the book is its 'index of collectability'. Twin criteria of rarity and desirability provide a rating system of from no to five stars, including half stars. Directly addressing the collector, this translates as a range from 'easily obtained and or dull' to 'categorically great but only one or two copies are known to exist' (e.g. Great British Heroes, Stereotypes on SRT). As an intervention into, as well as a description of, the market, these ratings undo the book's ambition to totalise the field. They also make apparent two features of the work overall.

Image: Cover of Great British Heroes

First and more simply, these ratings reflect a collector's experience of value, in that value accrued from rarity can not in the end be clearly separated out from the other values that might approximate ‘intrinsic' or ‘musical' value. Beyond the commonly shared experience of the inverse proportions that can come to obtain between familiarity and aesthetic effectiveness (hits becoming played out), there are the opportunity costs of acquisition that – akin to the uses of gold and lapis in Medieval art – mean that what is rare is partly considered beautiful because rare. In terms of identity formation, too, the appeal of owning something that that no one else or few people have is clearly aligned with the values of individualism. A five star possession means you are unique (and probably a contributor to the book!).

Secondly, as much as it makes a public performance of superior knowledge, the book is also and at the same time modestly blank in key respects. It fulfills a desire for mastery, and its primary audience of other collectors are faced with a flag planted at the highest point, a declaration that someone else got there first. In the great masculine pastime of knowing and having (music), it is a claim to know all, and perhaps implicitly to have all. (Whatever obscurity you might add to your ‘wants list' from this catalogue, it can no longer be your own discovery.) Yet, it is also an undeniably generous gift, inviting us to generate our own value from the information provided. Its comprehensiveness is fundamentally unevaluative, and leaving room for personal evaluation, contestation or confirmation of its claims. Listening value is rendered obscure with the factoring in of rarity. One star records compel us to repeat the work of the compilers, buying them and trying them ourselves.

Access to information about the records is one thing, of course, and access to the recordings themselves is another. Through the bootlegs mentioned above especially, many highly-starred rarities have entered into circulation, so that Revenge, Grout, Tinopeners and Anti-Social, for example, have been comparatively easy to get to hear since the 1990s. Even one of the very few five-star records, Great British Heroes, which has not been distributed on any vinyl reproduction, can be readily heard online, on the book-related blog.xvii It goes without saying that the collector?s market for the original artifacts survives and at this point is as much reinforced as undermined by this accessibility in reproduction.

Credited in the ‘thanks also' section in 45 Revolutions (p.vi), Chuck Warner has undertaken parallel research into the British (and other) punk and post punk scene(s), and availed himself of ‘the rise of mass communications' that depressed Debord, to contribute to the dissemination of the music.xviii Amongst his various projects, his Messthetics CD series (named after the Scritti Politti song) presents a comparably comprehensive documentation of British D.I.Y. records.xix Co-evolved with the book, his work offers a kind of audio parallel in working from an overview (in stark contrast to the hotchpotch of early bootlegs), but ordered geographically it avoids the alphabetical approach, narrating the backstories of social connections through venues, labels and personnel crossovers. Different areas of London have taken up two previous volumes (101 and 102), before the latest that introduces the scene around Camden associated with the Disco Zombies? Dining Out records and the punk crossover with the London Musicians Collective formed by the 49 Americans.

The dates of the recordings indicate that the coherence this volume traces in the social and aesthetic continuities exceeds 45 Revolutions' '76-'79 moment. Warner's selections are in themselves an interpretation of the archive, of course, but leave it over to us to value the various kinds of rarity they present. The general unavailability and beauty of the entire tracklisting – all previously uncompiled, un-digitised music – and the scarcity of the Avocados, the Jelly Babies and the Occult Chemistry track (from a flexidisk given away with Bikini Girl magazine) in their original media, are in this digital format for all intents and purposes equal with the cheaply available but underappreciated beauty of the two Methodischa Tune singles, not to mention the impossible rarity of the cassette released tracks and unreleased material. The limits of what will fit on a compact disc are one arbitrary dimension to what is included, but nothing is used for filler or completeness' sake, the aim being squarely on sharing the joys of entering into the horizons of the music.

Jon Bywater <j.bywater AT auckland.ac.nz> is a critic and a teacher who once wrote for The Jewish Beatle, 'New Zealand's only rock'n'roll magazine'.

Info:

Mario Panciera, 45 Revolutions (1976 / 1979) Punk, Mod / Powerpop, New Wave, NWOBHM, Indie Singles in the Years of Anarchy, Chaos and Destruction, Volume 1: UK / Ireland, Italy: Hurdy Gurdy Books, 2007.

Various Artists, Messthetics #107: D.I.Y. ‘78-'81 London III, Hyped to Death.com, http://www.hyped2death.com, 2009.

Footnotes

i Martha Defoe, International Discography of the New Wave, London: Omnibus Press, 1982, p. 606.

ii See an anonymous participant's account of the origination and competitive, variously authored iterations of the ‘Killed By Death' template, ‘ALL AMERICAN PUNK, NO FOREIGN JUNK: Rumors Debunked, Facts Ungunked', http://www.terminal-boredom.com/kbd.html

iii See, http://www.furious.com/perfect/recordfairs.html

iv See, http://.lowdownkids.com

v Walter Benjamin, ‘Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Book Collecting', in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, New York: Shocken, 1968, p. 66.

vi James Clifford, ‘On Collecting Art and Culture', in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988, p. 219.

vii Op. cit., 66.

viii Pancierra, op. cit., p. vii.

ix Ibid., xii.

x Benjamin, op. cit., p. 60.

xi Pancierra, op. cit., p. 557.

xii Ibid., ‘re: Crisis', p. 127.

xiii Ibid., ‘re: Zoot Alors', p. 831.

xiv Kugelberg, op. cit..

xv Clifford, op. cit., p. 218.

xvi Pancierra, op. cit., p. vii.

xvii See, http://45revolutions.blogspot.com

xviii For the credit, see, Pancierra, op. cit., p. vi.

xix For Chuck Warner's projects, see, http://www.hyped2death.com

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com