World War As Class War

Looking through the mists of obligatory sentimentalism that enveloped the 70th aniversary of the outbreak of WWII, James Heartfield remembers the pitiless subordination of people to production on all sides of that crisis

The labour question was not an afterthought in the Second World War. It was the greatest question of all. The victors in the national struggle were those who best mobilised their domestic workers and so best equipped their armies. The net impact of the war on the working class was that more of them worked much harder, and got paid less. Even in the biggest and most successful wartime economy, the US, personal consumption fell from 72 percent of output in 1938 to 51 per cent in 1945.

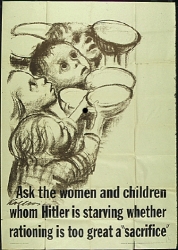

Image: A wartime poster by Jean Carlu

At the same time, the numbers in work grew by ten million and hours increased by a quarter. All of that excess production was going somewhere: it was going to fight the war. The sheer waste is beyond our wildest dreams. But the waste was not hurting everyone. Business, especially, US business, was reborn through the war effort. Like business across the globe, they needed new markets for the great amount of goods they made. The war fixed that.

Destructive as it was, the war laid the basis for new industry. Plants created in Detroit and Dagenham, the Urals and Silesia during the war would lay the basis for the post-war boom. 'A Nazi public utility like Volkswagen, or private utility like Daimler-Benz, laid down plant and equipment in the 1930s (and early 1940s) that would form the basis for post-war growth', says Mark Mazower.i Even in Soviet Russia 55 percent of the national income was given over to war production that would be the basis of industrialisation after.ii

Before one shot could be fired in the Second World War the bullets and the rifles, the uniforms, the trains and lorries to carry the soldiers, the steel to supply the munitions factories, the coal to furnace the steel, the oil to power the engines all had to be made, dug and drilled by another army, the industrial workforce. In the decade from 1935 to 1945 the warring nations turned their factories into engines of destruction. Between 1933 and 1936 US armaments spending rose from $628 million to $1.161 billion,by 1942 government awarded $100 billion to US business in military contracts.iii Between them, the Allied and Axis powers built 49.799 million guns, rifles and pistols, 1.8816 million tanks and 8.82 million ships between 1942 and 1944.iv The growth in output was phenomenal. Aircraft production was more than twenty times greater in 1944 than in 1935.

AIRCRAFT PRODUCTIONv

1935

1939

1941

1943

1944

Germany

3183

8295

11 776

24 807

39 807

Italy

1000

2000

2400

1600

0

Japan

952

4467

5088

16 693

28 180

United Kingdom

1140

7940

23 672

26 263

26 641

USA

459

2195

26 277

85 898

96 318

USSR

3578

10 832

15 735

34 900

40 3

To get this much out of industry, factories had to be placed under military discipline – not just in the Fascist countries, but in the democracies too.

The war changed the balance between labour and capital. Most think that it shifted the balance in labour's favour. The real lesson of the Second World War was that it crushed the independent organisations of the working class. In the Axis countries they were taken apart, before being re-made as company unions by the occupying powers. In the Allied countries, unions lost their independence and became recruiting sergeants for the war effort.

For the workers, wartime regimentation was hard graft on low wages. Business, though, made a fortune out of the war. During the four war years, 1942-1945, the 2,230 largest American firms reported earnings of $14.4 billion after taxes, up by 41 percent on the previous four.vi In Germany, too 'the higher level of the rate of exploitation which had been brought about by force was maintained for ten years after the period of fascism', wrote Elmar Altvater, 'the "West German economic miracle" was pre-programmed in the course of the "thousand year Reich".'vii Dragooning the workforce made more money for business.

In 1935 the Nazi regime began a compulsory system of workbooks. One copy was held by the employer another by the labour exchange. Workers were barred from leaving named key sectors, like aircraft and metal production.viii In 1938, Goering's decree for Securing Labour for Tasks of Special State Importance effectively conscripted labour. Within a year 1.9 million workers had been subject to compulsory work orders.ix Japan passed a General Mobilisation Law in 1938. Japanese civilians were barred from leaving work without the say-so of the local office of the National Employment Agency, under the Employee Turnover Prevention Ordinance (1940), and given work books from March 1941.x

In January 1940 the British Cabinet agreed to Ernest Bevin's proposals for a Register of Protected Establishments, and in March for a Register of Employment Order. Men up to the age of 46 had to be registered by 1941. Most agreed to reassignment after a talking to at the Labour Exchange, but one million directions had been issued by 1945, 80,000 to women. Under the Essential Work Order, workers were forbidden from leaving their jobs without permission – thirty thousand orders were made, covering six million workers. In 1943, 12,500 people were found guilty of breaking a Control of Employment Order. In this way Bevin boosted the armaments industry so that it ate up 37 percent of the workforce – up from 30 percent in a year.xi These were the people who sweated to make Vickers-Armstrong, ICI and Hawker-Siddeley into world class businesses.

Under New Zealand's National Service Emergency Act of 1942 it was an offence to leave or be 'absent from work without a reasonable excuse' in 'essential industries'.xii Australia's government wanted to direct labour but did not dare to overturn the rights of its states. In America, the War Manpower Commission's Chief Paul McNutt drew up a Worker Draft Bill that would have let him send labour to the North American Aviation Plant in Texas, and other war industries.xiii In the event, America's business lobby won the government over to the idea that they could recruit labour. In fact they signed up 17 million new workers between 1940 and 1944.xiv But as in Australia, the American authorities still kept butting in to regiment the factories – still they kept employers sweet with war contracts worth billions.

The Soviet Union already had forced labour. In 1941 it lost 33 million of its 85 million workforce, as well as two thirds of its coal, iron and steel production to the German invasion. But the method of forced industrialisation worked out in the 1930s was repeated by sending workers to the East, to rebuild new factories in the Urals.xv

In 1941, Roosevelt helped war profiteers by banning strikes and taking away labour legislation protections in the armaments industry.xvi In 1935 he had made a dispute procedure, the National Labour Relations Board, which barred wildcat strikes. In Britain, Order 1305 banned strikes.xvii In New Zealand Emergency Regulations of October 1939 banned strikes and inciting strikes.xviii In Nazi Germany a law on the National Organisation of Labour imposed the Führer-principle on the ‘shop community', with workers cast as ‘followers', while a Court of Honour heard labour disputes.xix By 1944 some 87,000 Germans had been jailed for breaking workplace rules, and in 1943, 5,336 of them were put to death.xx The model was Mussolini's Italy, where workers and bosses were put in the same corporations, and 'strikes, protest demonstrations and even verbal criticism of the government were illegal'.xxi The battle between labour and capital that had raged between the wars was settled when governments all over came down firmly on the side of industry.

Once they had clocked-off workers were not free from extra duties for the war effort. Before the war started, and unemployment was high, governments had experimented with different kinds of Labour Service to keep people busy. The Civilian Conservation Corps (1935) took a quarter of a million Americans off the unemployment register and put them to work clearing forests and building dams. In Germany, the Nazis forced everyone to do the Labour Service that had been set up for those out of work. In wartime this kind of compulsory volunteering became the norm. Herbert Morrison made six million Britons Fire Guards, who had to put in one night a week.xxii

Under the discipline of war, hours spent working for the boss were ratcheted up. Roosevelt twisted arms to get rid of American workers' overtime payments.xxiii In France the average working week went up from 35 hours in 1940 to 46.2 hours in March 1944 and decree laws increased hours in the armament industries to 60 a week.xxiv In New Zealand workers lost overtime and holiday entitlements, and hours were put up to 48 on the farms and 54 in defence factories.xxv In Germany, defence workers were put on a seventy-hour week, and a ceiling was put on wages in 1938.xxvi British men worked 47.7 hours a week in 1938, rising to 52.9 in 1943, but in a Factory Inspectorate survey of war plants, the sixty-hour week was the norm for men and women.xxvii Japanese authorities extended the working day to 11 or 12 hours in heavy industry.xxviii

The BBC's Music While You Work helped output, but in 1943 Roy Christison was arrested by the FBI for cutting the cable to the loudspeaker that played swing music at his shipyard though his workmates backed the protest.xxix Reichmusicführer Baldur von Blodheim published rules for the playing of Jazz that said 'preference is to be given to brisk compositions as opposed to slow ones (the so-called blues); however, the pace must not exceed a certain degree of allegro commensurate with the Aryan sense for discipline and moderation'.xxx

A sign that people were working harder was the rise in workplace injuries. In Germany from 1933 to 1940, accidents and illnesses at work rose from 929,000 cases to 2,253,000, occupational diseases from 11,000 cases to 23,000 and fatalities from 217 to 525 (outstripping the growth in employment from 13.5 to 20.8 million).xxxi So, too, in the US, 'long hours in hastily constructed industrial plants increased the rate of industrial accidents'.xxxii

Putting workers under army-like orders could happen because of the sacrifices made by the army. Civilians knew that if they stepped out of line, there was harsher work waiting for them in the army. The US Army was 11.4 million strong at its highest, the German 9.5 million, the Japanese 7.7 million, the British five million, the Italian 3.8 million and the Soviet 12.2 million.xxxiii

As well as moral pressure, bans on strikes, greater hours, telling people where to go, business also got the benefit of forced labour in civilian production. Most extensive was German forced labour from occupied Europe. Six million were sent from Holland, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Ukraine and Russia to slave in factories and offices in the Third Reich. Along with allied prisoners of war and German Jews, there were 7.128 million forced workers in 1944.xxxiv The conditions for these slave workers were terrible, and, for many, just the beginning of the end. The Japanese drafted thousands of young workers into industry under the General Mobilization Law. Also, the Japanese seized 700,000 Koreans and 40,000 Chinese, many to work in the mines.xxxv

The Allies used forced labour, too. Forty-eight thousand men aged 18 to 25 were sent down Britain's mines between 1943 and 1948. 21,000 seventeen year-olds forced to dig, like Jim Walters pictured here. They were called the 'Bevin Boys' after Labour Minister Ernest Bevin. One in every ten that were called up for National Service in the Army were sent to the mines – after their ID numbers were ‘pulled out of Ernie Bevin's hat'. More than a third appealed, and a few were jailed for refusing.xxxvi Conscientious Objectors, if they managed to convince a board of their sincerity, would then be forced to work in mines or on the land (composer Michael Tippet was jailed for three months for refusing). The Soviet Union's forced labour prisons, the Gulags, had 3.5 million inmates at the outbreak of war, though the number fell back as it went on.xxxvii

Like the Nazi authorities, the Allies were more brutal to subject peoples. On 1 August 1942 the British colony of Rhodesia passed a Compulsory Native Labour Act to force Xhosa people to work on settlers' farms and as labourers at the large air force bases.xxxviii Indigenous Chiefs selected the unhappy victims, or if not, the Native Commissioner would have to 'hunt the natives in the reserves until the required numbers were obtained'.xxxix In Brazil 55 000 people were drafted as 'Rubber Soldiers' to work in the Amazon under a deal between US President Roosevelt and the dictator, Getúlio Vargas to fill America's rubber shortage – hundreds died of malaria.xl

Prisoners of war were used as forced labour by everyone, despite the Geneva Convention. The Japanese made British and American captives into labour details – most infamously at Tamarkan; Germans enslaved Russian prisoners of war; Italian POWs worked Scottish farms; US Serviceman Kurt Vonnegut was put on a detail clearing bodies from the cellars of the firebombed city of Dresden, while the captured Italian partisan Primo Levi avoided the gas chambers by working as a chemist's assistant at Buna. And after the war, the Allies made defeated Germans into slaves. British and American forces gave the French 55,000 and 800,000 prisoners respectively. Britain took 400,000 German prisoners back home to work. America had some 600,000 at work in Europe and America.xli

A New Division of Labour

Business recruited a whole new labour force during the war. The people working the lathes, hammering the rivets, directing the traffic, ploughing the farms were not the same people they had been. Apart from skilled workers in protected trades, the male core of the working class was sent to war. Others – women, minorities, young people, migrant labour – were recruited to fill the gaps. These new workers were easier to handle at first and worked harder to prove themselves.

Roosevelt put ten million men into the American Army, and six million more women into the workforce. In 1940, one quarter of all workers were women, by 1945, more than a third were women (a share not repeated until 1960). Two fifths of workers in the airframe industry were women, and the United Auto Workers had 250,000 women members, the United Electrical Workers 300,000.

Between 1942 and 1945, the number of black Americans in work tripled. The number working in industry grew one and a half times to 1.250 million (300,000 of them women). The number of black people working as civil servants grew from 60,000 to 200,000. The great migration of black Americans from the rural South to Northern cities changed America. One million six hundred thousand black and white moved North – but then people were moving everywhere. Between 1940 and 1947 more than a fifth of the country, 25 million people, moved county, and four and a half million moved from the farm to the city for good.xlii

Britain was the first country ever to introduce conscription for women, and they were given the choice of war work instead. Those who refused could be fined up to five pounds a day, or imprisoned.xliii Two million more women were put to work in the war, a growth of 40 percent. In 1941 the Ministry of Labour worked out that four fifths of all single women aged 14 to 49 were at work or in the services. Among wives and widows, two fifths were working, but only 13 percent of those with children under 14 did.xliv Over 300,000 worked in the explosive and chemical industry, more than half their workforce, a million and a half in engineering and metal industries, 100,000 on the railways, thousands more on farms as part of the Women's' Land Army.xlv

Germany did not put many more women to work, even when war production minister Albert Speer begged the Führer to in 1942, but in 1943 new laws called for the registration of all women aged 17 to 45. These laws came too late to make a difference. Instead, Germany made up its shortfall of factory hands by bringing in six million foreign labourers from occupied Europe.xlvi From 1943 on, Speer changed the policy of bringing war workers in, by putting them to work making goods for the German war effort – but in France, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia and Poland. This had the advantage that factories in France were less likely to be bombed.

Speer's economic plan for Europe was a late flowering of the Grossdeutsche Reich that shows us one more way that the working class was re-made through the war. As well as a new division of labour at home, the war created a new international division of labour, too. This international division of labour was less driven by free trade than it was by forced seizure. Germany did not wring labour from its occupied states only. It took grain from Greece and Poland, oil from Rumania and the Caucasus, manufactured goods from France, Holland and Norway. The one-way traffic made a mockery of the Fascist Internationalism that Norway's pro-Nazi figurehead Vikdun Quisling dreamt about. In that way the work of yet millions more beyond Germany's pre-war borders were made to serve the German industry. In the Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere, four million Koreans and ten million Javanese were drafted into work by the Japanese authorities on plantations and some 200,000 were relocated for special projects like the Thai Burma Railroad. A further 365,000 Koreans were seconded by the Japanese Army for military and civilian work, while 200,000 were prostituted as 'Comfort Women'.xlvii

The Allies made a much deeper international division of labour too, firstly by the lend-lease programme that made America the 'Arsenal of Democracy'. Lend-lease extended free credit to Britain and other allies, without worrying too much about the terms of repayment. It was a brilliant way of getting American industry back to work, just when it was sliding back into recession. America's surplus output would be sent off to Europe, and the higher cause of war would put off the awkward point when the goods had to be paid for. This is the beginning of the system that made Ford, Chrysler, Douglas, IBM and Pan Am into world-beating businesses after the war.

Austerity

As well as working more people harder for longer, business and government worked together to hold down their wages – so boosting industry's operating profits. Holding down wages was not easy because putting so many more people to work ought to have pushed wages up. In fact, in cash terms, weekly wages did go up. But on closer inspection we find that hourly wages tended to go down. People were working for much longer hours, sometimes giving up their time for free, often losing out on overtime payments. What increases there were in wages did not keep pace with the increase in output.

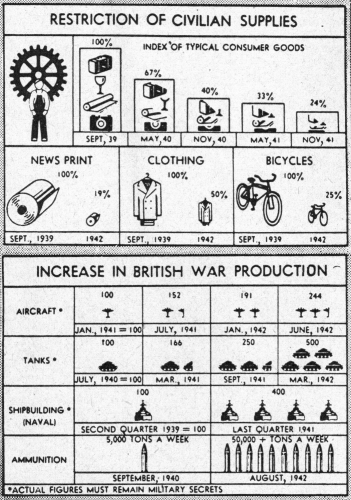

Also, the increase in cash wages did not buy more consumer goods. Governments intervened in the economy to grow the armaments and industrial firms not those that made consumer goods. People had more cash, but less to spend it on. Price rises swallowed up the bigger wage packets, and government war bonds soaked up the growth in savings. As they regimented the workplace to increase productivity, governments regimented social life, too, to keep consumer spending down, the better to boost investment in industry.

In Germany and Italy, the fascist governments drove wages down early on – by more than a quarter in Germany between 1933 and 1935, and by half in Italy, between 1927 and 1932.xlviii In the first year of Nazi rule, Krupp A.G.'s wage bill fell by two million RM while the workforce grew by 7,762, I.G. Farben's got a third more workers with just a 1.5 percent bigger wage bill.xlix After that, wages rose in Germany until the outbreak of the war, when living standards were cut again.l Even then, though weekly earnings rose by a quarter between 1932 and 1938, hourly rates were marginally down over the same period.li So it was in Britain between 1938 and 1943, where people had more cash in their pockets 'not because their rates were relatively better, but because they were putting in more hours'.lii Americans, too, were earning their extra wages by working more – by 1945 their hours were up by a quarter on 1938. Japanese industrial pay was cut by a fifth under the Wage Control Ordinances of 1939 and 1940.liii Italians' wages came to a standstill under the Fascists, so that by 1941 they were just 113 percent of what they had been in 1913.liv By the end of the war, under the Allies, consumption was only three quarters of what it had been in 1938, and the number of calories Italians had a day had fallen to 1,747.lv In Vichy and Occupied France real wages went down as wage controls proved much more effective than price controls.lvi

In America, a bigger wage bill was not matched by more goods in the shops, so business just put up prices to claw the money back. Around munitions plants housing was in short supply, transport was overcrowded and shop windows empty. The Department of Labor worked out that the 80 percent rise in cash wages between 1941 and 1945 was only a twenty percent rise when inflation and shortages were taken into account. Fortune reported from Pittsburgh 'to the workers it's a Tantalus situation: the luscious fruits of prosperity above their heads – receding as they try to pick them'.lvii Though they ate well enough, their clothes and household goods were shabbier as real incomes stagnated.lviii In Britain, too, more cash wages chased fewer goods to push prices up by half as much again between 1939 and 1941.lix In Germany, living costs were pushed up by a law allowing cartels to fix prices in 1935, and by 1941 household spending was down by a fifth from its already low point in 1938.lx

Governments grabbed workers' unspent cash for the war effort – handing it straight back to industry as payment on war contracts. In 1942 Americans were strong-armed to putting one tenth of their wages into war bonds, and in 1943 were taxed at source for the first time, a five percent victory tax.lxi Britons, too, felt the moral squeeze to put their money into National Savings at War Weapons Week (1941) Warship Weeks (1941 and 1942) Wings for Victory Weeks (two in 1943) and Salute the Soldier Week (1944). And like their American comrades, seven million manual workers had their first taste of Income Tax, when Pay As You Earn deductions were begun.lxii In Germany, where a War Bond issue had fallen flat in 1938, government raided the Sparkassen savings banks where people kept their spare cash for eight billion Reichsmarks in 1940 and 12.8 billion in 1941.lxiii

The greatest cut in working class income came through rationing. Food and clothing was rationed in Germany in the first two weeks of the war.lxiv In Britain meat, eggs, milk, butter and sugar were rationed from January 1940, canned meat, fish and vegetables from November 1941, followed by dried fruit and grains in January 1942, canned fruit and vegetables the following month, condensed milk and breakfast cereal in April, syrup in July, biscuits in August and Oatflakes and rolled oats by the end of 1942.lxv German rations were a healthy 2,570 calories for German civilians in 1939, but a cut in 1942 was found by scientists to lead to a loss of body fat in factory workers.lxvi It was under the Allies that German workers fared worst: their rations were cut to 1,100 calories in the American and British Zones.lxvii When the Nazis cut German civilian rations, they starved the Ostarbeiter in German factories, and, in 1940, rations for occupied Poles stood at 938 calories, while Jews rations were cut from 503 to 369.lxviii Italians' food was rationed from 1941. In Japan the rice ration of 0.736 pints was slowly adulterated with husks, and the standard calorie allowance cut from 2,400 in 1941 to 1,800 in 1945.lxix Food for workers was kept down so that more could be spent on building up industry.

The greatest cut in working class income came through rationing. Food and clothing was rationed in Germany in the first two weeks of the war.lxiv In Britain meat, eggs, milk, butter and sugar were rationed from January 1940, canned meat, fish and vegetables from November 1941, followed by dried fruit and grains in January 1942, canned fruit and vegetables the following month, condensed milk and breakfast cereal in April, syrup in July, biscuits in August and Oatflakes and rolled oats by the end of 1942.lxv German rations were a healthy 2,570 calories for German civilians in 1939, but a cut in 1942 was found by scientists to lead to a loss of body fat in factory workers.lxvi It was under the Allies that German workers fared worst: their rations were cut to 1,100 calories in the American and British Zones.lxvii When the Nazis cut German civilian rations, they starved the Ostarbeiter in German factories, and, in 1940, rations for occupied Poles stood at 938 calories, while Jews rations were cut from 503 to 369.lxviii Italians' food was rationed from 1941. In Japan the rice ration of 0.736 pints was slowly adulterated with husks, and the standard calorie allowance cut from 2,400 in 1941 to 1,800 in 1945.lxix Food for workers was kept down so that more could be spent on building up industry.

The rationing schemes in Britain and Germany were envied by US administrators, like Harry Hopkins, who warned Americans 'You Will be Mobilized':

Through forced savings and taxes, our spending will be limited and priorities far more widespread that at present will determine the kinds of food, clothing, housing and businesses which we will have, and will affect every detail of our daily lives. We should not be permitted to ride on a train, make a long distance telephone call, or send a telegram without evidence that these are necessary.lxx

To hold working class living standards down, authorities in Britain and Germany ordered their lives outside the factory as well as in. The German Strength through Joy clubs laid on theatre and exhibition visits, concerts, sport and hiking groups, dances, films and adult education courses. Strength through Joy's supported tourism was widely admired, though professional rather than working class members generally bagged the cruises. Its assets included two ocean liners and a car dealership, though delivery on instalments for the new people's car – Volkswagen – never materialised.lxxi

In Britain, the Entertainments National Service Association gave dinner-hour shows for factory workers. Shakespearean actors did pit-village shows (which they called 'missionary work' between themselves) for the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. Soon every hour of the day was planned, with CEMA-funded exhibitions by the Artists International Association, or a well-earned local authority Holiday at Home. Like the Strength through Joy clubs, people remember the comradeship at the workplace concerts and lectures with happiness. Still, these cultural offerings were laid on to cut the costs of out-of-work pastimes and keep the men and women happy at their benches and desks – working to win the war, and enrich their employers.

Propaganda put 'guns before butter' – in the infamous words of Hitler's propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, parodied by John Heartfield in a 1935 poster. In Italy a pompous Mussolini had told the Chamber of Deputies in 1934 that 'we are approaching a period in which mankind will find its equilibrium on a lower standard of life'.lxxii The Japanese press lauded the Aichi Watch Company's new 'family wage system' as 'livelihood, family-oriented wages' as distinct from the 'western, selfish, individualistic, skill-based wages'.lxxiii In Britain Lord Beaverbrook bullied housewives into giving up their aluminium saucepans to make Spitfires – even though metal merchants protested that there was an aluminium glut at the time. To underscore the point he had all the iron railings taken away, too. After the war the railings were discovered in a hangar in Ulster, intact. Nobody knows whether the saucepans were ever airborne, only that they made no more costly meals.

Image: John Heartfield poster mocking Goebbels' 'guns before butter'

Cutting back on household goods changed the balance of industry. Businesses and factories that were making goods for home use were changed over to munitions, guns, uniforms, tanks and aeroplanes. In America Walter Reuther of the Union of Auto Workers put forward a plan to convert car plants to war work. Though Auto Executives smarted at being told what to do by the Socialist leader, by 1943 'about 66 percent of all pre-war machine production had been converted to aircraft production'.lxxiv Between 1938 and 1944 the output of Germany's consumer goods industry fell from 31 percent of all output to just 22 percent. In Britain, output of beef and veal fell by a sixth, eggs by a half and pigmeat by two-thirds Soviet workers in civilian goods and services were cut by 60 percent.lxxv

Workers wages were held down even though the factories were full. That made sure a greater share of the national wealth went to the war, and to business.

Labour's Reaction

In the ten years from 1935 to 1945 the working classes across the world were pushed harder in greater numbers to produce much more. Those changes would not have been possible without a shift in the terms between workers and bosses – not just on a plant by plant basis, but country-wide, and world wide. That shift happened worldwide. But its terms were not the same country by country. The difference between the national terms of the deal between capital and labour are the key to the broader differences between the fascist countries and the democracies.

The NSDAP in Germany, like Mussolini's Fascist party had come to power on a programme of crushing Bolshevism – which was a code for crushing the labour movement (its more militant activists being Communists). In March 1933, after the Dutch anarchist Marinus van der Lubbe burned down the parliament building, 100,000 Communists, Social Democrats and trade unionists were put in new concentration camps, and 600 killed. On May Day 1933, the leaders of the Trade Unions marched behind the Swastika, hoping to curry favour with the Nazis. On the 2nd of May union offices were occupied by brown shirts, the premises and assets seized by emergency decree.lxxvi The working class were made to kneel before the Fuhrer or get sent to the camps, and their own unions were broken up.

Nazi Robert Ley led a substitute Labour Front that, being based on workplace subscriptions like the unions it replaced, was much bigger than the Nazis' old union faction the NSBO. Indeed the Labour Front quickly became one of the weightiest bodies in the Nazi state, with a lot of room to manoeuvre. The Nazis thought that they were different from the other right-wing parties because they were carrying the German worker with them, not just taking a whip to him. The masses did support the war, most of all in the early years of victory, and they joined in the big rallies. But there was a gap between rulers and ruled that, ironically, made the fascist state the less efficient at war-time mobilisation.lxxvii

In Japan there was strife in the workplace between the wars, but union membership was only 6.8 percent of the workforce. The Sanpo (short for Sangyo Hokokukai) movement that wanted respect for workers' industrial contribution to the nation very quickly took the unions' place covering 70 percent of the workforce, or 5.5 million members at its height in 1942. Started by some right-wing union leaders and intellectuals, Sanpo was pushed onto employers first by the Aichi Prefecture Police Department, and then later the Labor Ministry. Sanpo set up workplace committees to talk through problems. Very quickly Sanpo turned into a semi-official body that dealt mostly with absenteeism, productivity and efficiency. The workers' keenness at the start turned to distrust.lxxviii

Image: A Ministry of Information poster explaining to Americans that Britons are being starved to boost production

In Britain, the deal between labour and government was different from the German one. Instead of just coercion, the government and the bosses got the leaders of the trade unions onside. The trade union officials' support for the war was strong. Engineers' Union (AEU) president Jack Tanner – who had fought bitter battles with employers in the first world war - was thrilled:

This is an engineer's war [...] It is a machine war with a vengeance. Whether it is in the anti-aircraft defences or the machines on land and sea, or in the sky, it is the engineer who stands behind them all.lxxix

Seats on Joint Production Committees lured trade unionists to give their all for the war effort. These were set up to plan ways of boosting output, and after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, British Communists got behind them. A deal between the AEU and the Engineering Employers Federation brokered by Ernest Bevin in March 1942 founded JPCs in the Royal Ordinance Factories, and that month 180 JPCs answered an AEU survey. 'Once the political conviction of the workers has been won', Walter Swanson told the Engineering Allied Trades Shop Stewards Committee, 'they will display an initiative, drive and energy to increase production never witnessed in this country before'.lxxx

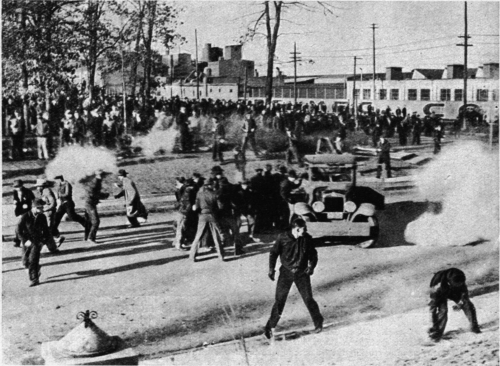

Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour (7 December 1941) the Roosevelt government was tilting towards the use of force to control Labour. When the United Auto Workers struck out Allis-Chalmers in early 1941 the Office of Production Management (OPM) and Navy Secretary Frank Knox ordered the men back to work, and police in armoured cars opened fire on picket lines. The June strike at North American Aviation prompted President Roosevelt to open the plant by force, using 3,500 federal troops to quell this national emergency.lxxxi The government's despotic moves were tough for the Confederation of Industrial Organisations (CIO) to take. Though its membership was more militant that the rival, craft-based American Federation of Labour, its leaders had tried hard to win influence in Roosevelt's New Deal administration, supporting the National Labor Relations Board. After Pearl Harbour, the CIO got patriotic and offered a 'No Strike' pledge. Leader Philip Murray told the CIO convention two weeks later: 'I say to the government of the United States of America, the national CIO is here with its heart, its mind, its body [...] prepared to make whatever sacrifices are necessary.'lxxxii

The no-strike pledge worked – at least for the first two years of the war – and strikes were down. Roosevelt used the no-strike pledge to take away overtime and weekend work payments. In April 1942 Roosevelt summoned CIO and AFL leaders to a 'War Cabinet' and told them they would have voluntary wage stabilization. He told a meeting of Shipyard Owners, government officials and union officers in May 'the full percentage wage increase for which your contracts call, and to which by the letter of the law you are entitled, is irreconcilable with the national policy to control the cost of living'.lxxxiii To make the wage freeze work for the union leaders, if not their members, Roosevelt introduced a 'Maintenance of Membership' clause, preventing workers from moving unions to get a better deal. The War Production Board set up 1,700 labour-management production committees at the prompting of the (CIO) on the understanding that they were 'solely to increase morale and boost production'.lxxxiv But these never got the CIO the corporate status that British Unions won, as US employers jealously guarded their rights.

In both Vichy and Occupied France, national trade unions were abolished and strikes outlawed. Those that did take place, like the Nord Miners' strike of May 1941 were violently suppressed. In place of unions, French workers in Vichy were invited to sit on Comités Sociaux alongside managers and employers.lxxxv

Image: Striking Milwaukee munitions workers tear gassed by State Troopers

Where they took on the cause of the war as their own, workers in many countries sacrificed a great deal for victory. Loyalty did not come all at once, but built up, over the course of the war. Workers, like everyone else, cheered when their side won, and were angry when they were attacked.

The 'blitzkrieg' motorised invasion of the old enemy France thrilled many Germans. It was a victory that cost them very little. Britons, sceptical about the Phoney War between 1939 and 1941 were gripped by the drama of Dunkirk when the British Expeditionary Force were saved by 'a flotilla of small ships' – in the words of J.B. Priestley's radio broadcast. The myth that civilian volunteers had rescued the army was not true – those ships that did take part were commandeered. Still the Ministry of Information understood that the divide between the armed services and the population had been broken down – in spirit if not in fact. Americans, not won over to Roosevelt's pro-British policy, were stung into action by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The wider fight stirred patriotism on the shop floor. From New Orleans, the Office of War Information got this telegram: 'Please rush gruesome photos of dead America soldiers for plant promotion Third War Loan'.lxxxvi

German morale was actually boosted by the great bombing raids on cities and even by the losses to the Red Army – all of which let the Nazis pose as defenders of the nation.lxxxvii To everyone's dismay Roosevelt's Strategic Bombing Survey found that the bombing raids on industrial towns tended to make output higher than it had been before.lxxxviii

Governing the economy was the key to fighting the war. It was also the reason that the war was fought at all. The war was a war of conquest, where military victory enslaved defeated peoples. Even the liberation of Europe set the scene for a new conquest of the working class at the hands of a re-born capitalism.

James Heartfield <Heartfield AT blueyonder.co.uk> is the author of Green Capitalism, (OpenMute, 2008) Let's Build! Why we need five million new homes in the next 10 years, (Audacity, 2006), The Creativity Gap, (Blueprint, 2005) and The ‘Death of the Subject' Explained (Sheffield Hallam U., 2002). He lives in Archway, north London, and is currently based at the Centre for the Study of Democracy, University of Westminster. See, http://www.heartfield.org

Footnotes

i Mark Mazower, Dark Continent: Europe's Twentieth Century, London: Vintage, 2000, p. 130.

ii Alec Nove, An Economic History of the USSR, London: Penguin, 1982, p. 279.

iiiFor Armaments spending 1933-6, Rajani Palme Dutt, World Politics: 1918-1936, London, Victor Gollencz, 1936, p. 15. For military contracts in 1942, Thomas Fleming, The New Dealers' War: FDR and the War Within World War II, New York: Basic Books, 2002, p. 124.

iv Adam Tooze, Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, London: Viking Adult, 2007, p. 641.

v Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, London: Vintage, 1989, pp. 419 and 455.

vi Jacques R. Pauwels, The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War, Toronto: J. Lorimer, 2002, p. 71.

vii Elmar Altvater, , Jurgen Hoffman, Wolfgang Sholler and Will Semmler, 'On the Analysis of Imperialism in the Metropolitan Countries', Bulletin of the Conference of Socialist Economists, London: Spring, 1974, pp. 7 and 9.

viii David Schoenbaum, Hitler's Social Revolution: Class Status in Nazi Germany, 1933-1939, London: Norton, 1997, p. 92.

ix Tooze, op. cit., p. 261.

x Andrew Gordon, The Evolution of Labor Relations in Japan: Heavy Industry, 1853-1955, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988, pp. 258 and 268.

xi Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain, 1939-45, London: Plimlico, 1992, pp. 272-3.

xii W.B. Sutch, Workers and the War Effort, Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Co-operative Publishing Society, 1942, p 46-7.

xiii Fleming, op. cit., p. 248.

xiv Stephen Kotkin, ‘World War Two and Labor: A Lost Cause?', International Labor and Working-Class History, No, 58, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 186.

xv Alec Nove, op. cit., p. 272.

xvi Fleming, op. cit., p. 82.

xvii Calder, op. cit., pp. 133 and 456.

xviii W.B. Sutch, op. cit., p. 17.

xix Schoenbaum, op. cit., pp. 86-8.

xx Gabriel Kolko, A Century of War: Politics, Conflicts, and Society Since 1914, New York: The New Press, 1994, p. 242.

xxi Edward Tannenbaum, Fascism in Italy: Society and Culture, 1922-1945, London: Allen Lane, 1972, p. 120.

xxii Calder, op. cit., p. 392.

xxiii Nelson Lichtenstein, Labor's War at Home: The CIO in World War II, Philidelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003, p. 96; Fleming, op. cit., p. 153.

xxiv For standard working hours, Robert Paxton, Vichy France, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, p 376. For the output increases that would later equip the German army, Alan Clinton, Jean Moulin, 1899-1943: The French Resistence and the Republic, New York: Palgrave, 2002, p. 73.

xxv Sutch, op. cit..

xxvi For the hours of week per week, see, ‘A Letter From Germany', International Communist Correspondence, Vol. III, No 1, January 1937, p. 22. For the wage ceiling, see, Schoenbaum, op. cit. p. 97.

xxviiSee, Calder, op. cit., p. 405 and John Costello, Love, Sex and War: Changing Values, 1939-45, London: Pan Books, 1986, p. 207.

xxviii Gordon, op. cit., p. 314.

xxix Sally M. Miller and Daniel A. Cornford, Eds., American Labor in the Era of World War II, Westport, CT: Praeger, 1995, p. 94.

xxx Katherine Morley and Tim Nunn, ‘The Arts and the Holocaust', East Renfrewshire Council, 2005, p. 110, http://www.reelingwrithing.com/holocaust/download.htm

xxxi Robert Black, Fascism in Germany: How Hitler Destroyed the World's Most Powerful Labor Movement, London: Steyne, 1975, p. 989.

xxxii Hugh Rockoff ‘The United States: from ploughshares to swords' in Mark Harrison, ed., The Economics of World War Two: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 94.

xxxiii Mark Harrison, ‘The Economics of World War II: an overview' in Ibid., p. 14.

xxxiv Werner Abelshauser, ‘Germany: guns, butter and economic miracles' in Ibid., p. 161.

xxxv Kotkin, op. cit., 184.

xxxvi Calder, op. cit., p. 505.

xxxvii Kotkin, op. cit., p. 186.

xxxviii David Johnson, World War Two and the Scramble for Labour in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1939-1948, Harare, Zimbabwe: University of Zimbabwe, 2000, p 89.

xxxix Ibid., 100.

xl Larry Rohter, ‘Of Rubber and Blood in Brazilian Amazon', New York Times, 23 November, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/23/world/americas/23brazil.html

xli James Bacque, Crimes and Mercies: The Fate of German Civilians under Allied Occupation, 1944-50, London: Little Brown, 1997, p. 61.

xlii Miller and Cornford, op. cit., pp. 2-3.

xliii Costello, op. cit., p. 211.

xliv Ibid., p. 197.

xlv Calder, op. cit., p. 386.

xlvi Costello, op. cit., p. 215.

xlvii Kotkin, op. cit., p. 184.

xlviii Guerin, op. cit., p. 194-5.

xlix Black, op. cit., p. 989.

l Tim Mason, Social Policy in the Third Reich: The Working Class and the ‘National Community', 1818-1939, Oxford: Berg Publishing, 1993, p. 39.

li Schoenbaum, op. cit., p. 98.

lii Calder, op. cit., p. 405.

liii Gordon, op cit., p. 285.

liv Vera Zamagni, The Economic History of Italy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 309.

lv Vera Zamagni, ‘How to Lose the War and Win the Peace', in Harrison, op. cit., pp. 179 and 191.

lvi Paxton, op. cit., p. 376.

lvii Lichtenstein, op. cit., p. 112-3.

lviii Rockoff, op. cit., p. 93.

lix Calder, op. cit., p.275.

lx Schoenbaum, op. cit., p. 126; Tooze, op. cit., p. 353.

lxi Lichtenstein, op. cit., p. 112.

lxii Calder, op. cit., p. 410-11

lxiii Tooze, op. cit., p. 354.

lxiv Ibid., p. 356.

lxv Calder, op. cit., p. 318.

lxvi Tooze, op. cit., pp. 361 and 541.

lxvii Patricia Meehan, A Strange Enemy People: Germany under the British, 1945-50, London: Peter Owen, 2001, pp. 248 and 253.

lxviii Tooze, op. cit., pp. 542 and 366.

lxix Akira Hara, in Mark Harrison, The Economics of World War Two, 255-6

lxx From an article in Fortune, December 1942, reprinted as Harry Hopkins, ‘You Will Be Mobilized', The Reader's Digest, February 1943.

lxxi Schoenbaum, op. cit., pp. 105-7.

lxxii Franz L. Neumann, European Trade Unionism and Politics, New York: League for Industial Democracy, 1936, p. 42.

lxxiii Gordon, op cit., p. 256.

lxxiv Lichtenstein, op. cit., p. 88.

lxxv Abelshauser, op. cit., p. 153; Calder, op. cit., p. 486; Kotkin, op. cit., p. 186.

lxxvi Richard Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, London: Penguin, 2004, pp. 348 and 355-357

lxxvii Milward, A.J.P. Taylor

lxxviii Gordon, op. cit., p. 299; Tetsuji Okazaki, ‘"Voice" and "Exit" in Japanese Firms During the Second World War: Sanpo Revisited', Economic History Review, Vol. 59, No. 2, 2006.

lxxix Presidential Address, July 1940, in Nina Fishman, The British Communist Party and the Trade Unions, 1933-1945, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 1995, p. 263.

lxxx In Ibid., p. 298 – the speech was written by C.P theoretician Rajani Palme Dutt

lxxxi Art Preis, Labor's Giant Step: The First Twenty Years of the CIO: 1936-55, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972, pp. 114-7.

lxxxii Ibid., p. 131.

lxxxiii Ibid., p. 154.

lxxxiv Lichtenstein, op. cit., p. 89.

lxxxv Paxton, op. cit., p. 376.

lxxxvi Fleming, op. cit., p. 381.

lxxxvii Timothy W. Mason, Nazism, Fascism and the Working Class, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 265.

lxxxviii Fleming, op. cit., pp. 529-30.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com