War is my Business, and Business is Good

Francesca X visits London’s Defence Systems and Equipment International fair (DSEI), and discovers that under cover of a ‘meet and greet’ event, business is brisk

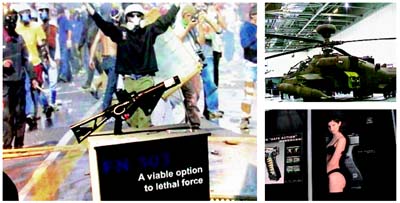

Early morning: thousands of delegates are crowded together in a tube station in Docklands, East London. Clutching compact travel suitcases and dressed in tailored suits, they are waiting patiently in line to enter the ExCel centre, a modern exhibition complex in London’s Docklands hosting Defence Systems and Equipment International. DSEI, Europe’s biggest arms fair, is a huge weapons supermarket organised by Spearhead Exhibitions Ltd., with the political and economic support of the British Government. It hosts more than 1,000 arms companies and 80 government representatives who come to meet international buyers for their small arms, missiles, planes, tanks, military electronics and warships, as well as surveillance and riot control equipment. This year’s DSEI cost British taxpayers at least £1.5m in subsidies and extra policing. Since the Labour government was elected in 1997, the UK has licensed arms and military equipment to 20 countries engaged in serious conflict. 14 of these countries were invited to DSEI 2001 and many received invitations to DSEI 2003. Conspicuously missing from the British Defence Ministry’s official invitation list were 20 countries that include some of the world’s worst human rights-abusing states; but a second invitation list, drafted by Spearhead, made sure that these countries – including Israel, Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, China and Russia – were present at DSEI. Under the 2002 Arms Control Act, it is illegal for UK companies to sell arms to regimes which could use the weapons for either internal repression or external aggression – but, taking the Spearhead list into account, that’s around half the countries attending the event. As far as the organisers are prepared to admit publicly, ‘Nobody is selling or buying weapons at DSEI. People come to meet, to get to know each other and to do public relations.’ But delegates and salesmen within the fair beg to differ. ‘DSEI is a trade fair,’ admits Italian DSEI representative Iva De Mari. The spokesperson of the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company (EADS) concurs: ‘You do real business, make agreements, define the general lines for stipulations that will be signed later on. It’s wonderful, instead of travelling like crazy around the world, we can come here every two years and do excellent business.’ Among the list of weapons which manufacturers have been requested to exclude from the DSEI this year are cluster bombs, which scatter small explosive bomblets over a wide area, causing indiscriminate casualties, and which often remain undefused long after the cessation of ‘hostilities’. Unexploded weapons like these have caused more than a thousand infant deaths in Iraq and are now considered ‘inappropriate’ for the UK market, even though British and US forces used them extensively in Iraq. At the Ruag stand – the Swiss-based world leader in cluster bombs – a very irritated delegate claimed not to have brought any examples. ‘We didn’t bring them. You want to see one? Go ask the Turks.’ But at MKEK, the Turkish State company which since 1995 has shipped small arms to Botswana, Burundi, Chile, Libya and Pakistan, the manager’s lips were sealed. Smiths Group plc., the British company which manufactures the missile trigger system for the US-supplied Apache attack helicopters used by Israel against Palestinians, likewise kept schtum. Eventually the prohibited cluster bombs do turn up, in the catalogue of the Israel Military Industry, listed as ‘cargo ammunition’. And what about depleted uranium, a toxic heavy metal which causes a wide range of cancers and foetal abnormalities, which pollutes soil, rivers and cities, with effects lasting for hundreds of years? This too is on sale at DSEI. Also starring is the Fn303n, a ‘less than lethal’ lancer used in Geneva to scar the face of Swiss syndicalist Denise Chervet. A huge poster of the anti-G8 riots dominates the stand of Fn Herstal, the Belgian company that makes the device.

‘It doesn’t hurt,’ says the Fn Herstal communication manager, ‘but it can stop protesters from being violent. Of course it depends on how police will use it... We recommend to aim at the chest, but in the end it’s up to police how they use it.’ Asked about the injured protestor, the Fn Herstal employee says the Swiss woman was hurt because ‘she moved’ – and asks for our camera to be turned off. Meanwhile euphemism and broad smiles are the rule: the arms dealers never talk openly about bombs, only about ‘equipment’ – not weapons but ‘integrated defence systems’. There is never mention of the ongoing world war: everything is a simulation. The most extreme example is a live combat ‘performance’ by British soldiers just back from Iraq, showing off their nice war tools as if it was all just a virtual game for big boys.

The traders are willing to talk to journalists, and, because getting press accreditation is so difficult that the press is almost exclusively a specialised military one, they’re sometimes caught off their guard, apparently quite unconscious of their behaviour, their words or the sales images they’re using. One official is winking at women and blowing kisses; two old men are repairing a gun in front of a poster of a woman in a bikini with a machine gun between her legs... Amid the radar and Tomahawk missiles, Apache helicopters, guns, grenades, flight simulations and ‘less lethal weapons’, the businessmen seem to be enjoying the event a great deal. ‘This year it’s very well organised,’ says one senior Italian official. ‘I never saw so many official delegations... it’s great to come here and to get updated on the newest war technologies.’ By 5pm the arms traders are outside the centre, moving towards their hotels on public transport, merging into the stream of other businessmen and office workers. Outside the ExCel centre, a broad platform of different groups have organised three days of blockades, colourful demos, Critical Mass demonstrations, and actions in an attempt to disrupt the arms show. A few protesters brought the Docklands Light Railway to a virtual standstill by chaining themselves to the front of trains, placing cycle locks around their necks. In the centre of London, the Trafalgar Square fountain ran red with symbolic blood. To protect the arms dealers from these ‘violent’ protesters and their cardboard tanks, more than 2,600 security guards and police officers guarded the DSEI site, a security bill of more than £1million for the British taxpayer. During four days of protest, police arrested 150 people under the Terrorism Act 2000. Civil rights group Liberty denounced this illegal use of antiterrorism measures against legitimate protesters but at the ExCel centre, the arms dealers seemed to share the police’s view of the protesters outside: ‘They don’t understand. What we do, it’s about self-defence – not about making problems, about conflict.’ Inside the elite club of the DSEI, it seems possible that the war professionals, excited by the prospects of business, might really believe this.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com