To Be a Pilgrim

Helen Macfarlane was a Chartist revolutionary, the translator who put the ‘hobgoblin’ in the Communist Manifesto, and an advocate of ‘the total demolition of the present system of things’ on Christian grounds. Peter Linebaugh welcomes the 150 years-overdue publication of her writings, invoking the Blood and Fire of that earlier ‘ruthless critic of everything that exists’, John Bunyan

On Christmas morning 2014 a dear anarchist friend, doubtless an atheist for all intents and purposes, sang in a near whisper as if only to himself his mother’s favourite hymn, which had been sung at her funeral,

Who would true valour seek,

Let him come hither;

One here will constant be,

Come wind, come weather

There’s no discouragement

Shall make him once relent

His avowed intent

To be a pilgrim.

The pilgrim is a traveller, a wanderer, a wayfarer. This is the first meaning. Secondarily, the pilgrim is defined by destination, a sacred place. The pilgrim shares mobility with the proletarian who has lost roots in land. S/he has become deracinated, s/he is forced to move along, as the copper says. The difference between proletarian and pilgrim arises in volition. The pilgrim seeks true valour; the proletarian a wage. Pilgrim’s Progress is at once a book of the proletarian condition and written by a proletarian, John Bunyan. It is in that book the hymn first appears. It continues,

Whoso beset him round

With dismal stories,

Do but themselves confound;

His strength the more is.

No lion can him fright,

He’ll with a giant fight,

But he will have a right

To be a pilgrim.

The pilgrim is like the Biblical David who bearded a lion and who killed Goliath, the giant of the Philistines, by simplicity and true valour. The dismal, confounding stories are the false ideology we meet in school, the constant barrage of bullshit on the TV, the lying rhetoric of advertisement, and the formula of political speeches. The dominating media express twaddle or humbug or pure fudge as Helen Macfarlane would say. Against them the pilgrim seeks another way to revolution or the promised land.

Helen Macfarlane was a Chartist revolutionary. She was from a family of Scottish calico printers near Glasgow. Born in 1818, the same year as Karl Marx whose Communist Manifesto (1848) she was the first to translate into English (1850). She was well prepared for this, having been Hegel’s translator into English. In Vienna she participated in the 1848 Revolution, a ‘universal tumbling of impostors.’ She returned to England and worked with Marx and Engels. She lived in Lancashire and in London (Great Titchfield Street). After the collapse of the Chartist ‘Land Plan,’ she emigrated to Natal, South Africa, in 1852. (Her brother was an agent for an emigration company.) On the voyage out her husband abandoned her, her daughter perished in Durban, and she returned to England a year later and re-married, this time to a radical clergyman. She died at the age of 41 in 1860.

Her own view of history was Hegelian. History has gone through four stages or periods. The first presented the democratic idea in the struggle of early Christianity against the structures of the Roman Empire. The second was the Reformation. The third was the Enlightenment, and the fourth was the proletarian revolution of her own time, incarnating the spirit of the age – liberty, equality and fraternity. The fourth stage belonged partly to the future. This is the basis of her evangelicalism. Hegel’s philosophy was to her ‘quite simply a translation of Jesus’s revolutionary, egalitarian humanism into a world without gods or mystery.’ Jesus and Hegel demonstrated the identity of divine and human nature.

Image: Masthead for The Red Republican, 1850-51

She frequently refers to Christianity, not as the source of a messianic change but as the advent of the idea of universal equality and hence universal divinity. To her, the mythos of the resurrection was revolutionary, namely, that humanity can rise. Jesus is called the gentle Nazarean, the Galilean carpenter’s son, the Nazarean proletarian, the Nazarean teacher, our martyred Galilean brother, the Galilean carpenter, the poor despised Jewish proletarian, the Galilean Republican, the sans-culotte Jesus.

The Holy Spirit of truth, which the Nazarean promised to his followers, as a guide on their weary pilgrimage towards the promised land – towards a pure Democracy, where freedom and equality will be the acknowledged birth-right of every human being; the golden age, sung by the poets and prophets of all times and nations, from Hesiod and Isaiah, to Cervantes and Shelley; the Paradise, which was never lost, for it lives – not backwards, in the infancy and youth of humanity – but in the future, as the bright prize destined for the ripe manhood of the human race; this spirit, I say, has descended now upon the multitudes, and has consecrated them to the service of the new – and yet old – religion of Socialist Democracy.

– Red Republican, 22 June 1850.

She detested ‘the lawn sleeves of consecrated bishops and the wigs of learned judges, to be so many rags’. She demanded ‘the total demolition of the present system of things.’ ‘The most pressing work of the new epoch is the work of destruction.’ The domination of the middle class is ‘a system of bourgeois terrorism.’ She denounced bourgeois twaddle, humbug, and fudge. She calls for ‘throwing off the whole superstructure of scholastic theology as a dead weight,’ not something that could easily be said by someone unfamiliar with the odour of sanctity.

Yet she had learned her scholastic lessons. She quotes St Augustine, St Ambrose (‘Let them know that the earth, from which they were created, is the common property of all men’), St. John Chrysostomus (‘Behold the idea we ought to have concerning rich and avaricious men. They are robbers’), and St. Basil (‘Who is the robber? It is he who appropriates to himself the things which belong to all.’). She remembers the early Christians for whom ‘there was none among who wanted, for they had all things in common.’ (Acts 4:32) She quoted Luke, the land is a common gift to all; she favoured its nationalisation. She advocated criminal prosecutions against the land-owning class as well as ‘the thimble-riggers of the Stock Exchange.’

Democracy, she said, was ‘a soul in want of a body.’ She advocated ‘a republic without helots; without poor; without classes; without hereditary hewers of wood and drawers of water; without slaves, whether chattel or wage-slaves.’ To her inequality and selfishness were opposite of Christian principles, i.e., they were, she says, ‘pagan.’

Image: John Bunyan's tomb, Bunhill Fields London

English Chartism, like English revolutionaries of every period, was deeply influenced by the Protestantism of the English Revolution. Protestantism was the dominant ideological force. When we remember that there was no TV or cell phones no internet or electronic media, we comprehend the importance of the church as a place of meeting, congregation, and communication. The Bible, sermons and hymns transmitted ideas.

E.P. Thompson and Christopher Hill were formed by this Protestantism. Their ‘history from below’ owes much to John Bunyan: Hill was his biographer (A Tinker and a Poor Man) and Thompson celebrated his importance at the very beginning of The Making of the English Working Class with extensive paraphrases from Pilgrim’s Progress. Thompson of course was critical, but his criticisms could not conceal his delight, even joy, in the pilgrim. Thompson and Hill were both Communists, members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Dorothy Thompson, Edward’s wife and comrade, has been called the pre-eminent historian of Chartism. What does she say about the Protestantism of that mass movement? In her latest collection of essays Dorothy Thompson does not mention Helen Macfarlane.

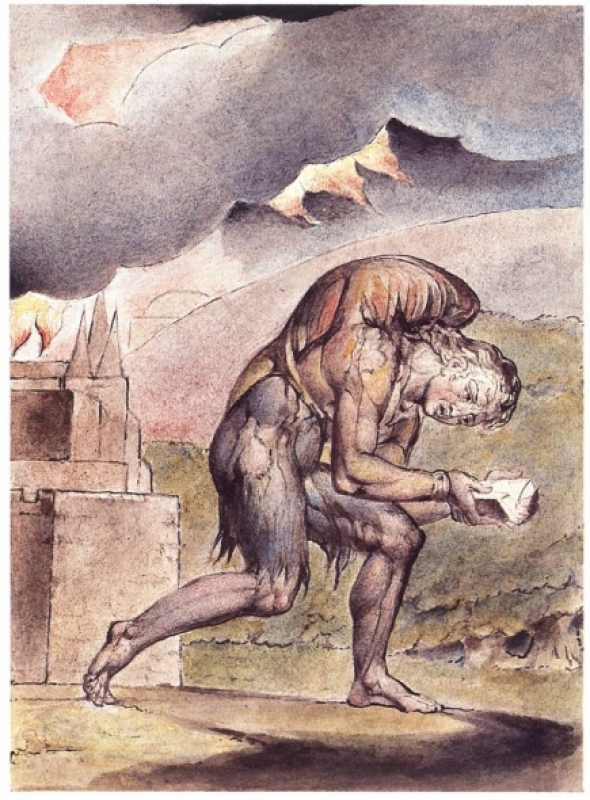

Bunyan’s allegorical power comes from the combination of a) the psychological insights derived from his actual experience as a veteran, as homeless, as a tinker, as an ex-prisoner, with b) the application of doctrine. The doctrine stems from Christianity with its various and contradictory notions of deity – trinitarian, monotheistic, incarnate, in history, in the sky, in the soul, in nature, everywhere! Bunyan's allegory presents the subjectivity of the pilgrim through a familiar landscape – countryside and market town, castle and cottage – and a powerful process of naming, not the traditional virtues and vices, sins venal and mortal, but names corresponding to the intricacies of a hierarchical social structure. Lord Hate-good, Mr Lyar, Sir Having Greedy, Lord Carnal Delight, Mr By-ends, Mr Money-love of the town of Coveting, and on and on in a moralizing carnival of identity politics. The pilgrim’s psyche is thus rooted in social and material life. Helen Macfarlane presents the subjectivity of the Proletarian: she will instruct, flatter, cajole, warn, and scold ‘brother Proletarian.’ Her approach is evangelical.

Thompson contrasts the Puritan and the Dissenter: from active affirmation in the 17th century to passive defence in the 18th century. The pilgrim is yet a third type, one more easily found in the Communist party organiser, the trade union activist, the messenger in the guerrilla war of liberation. What meaning can the pilgrim have for us? Itinerancy has become one of the conditions of the precariat; it might be likened to the wanderjahre of medieval journeymen. The pilgrim sees that defeat is partly within, and thus revolution requires introspection or, to formulate this in another way, the defeat without has consequences within, and thus individual physical and mental health requires revolution.

Image: A Pilgrim, stone relief carved on John Bunyan's Tomb, Bunhill Fields London

In addition to some Dissenting or Methodist pulpits, the Chartists also had a press, the unstamped press, and this is where Helen Macfarlane published her translation of The Communist Manifesto. It appeared in four weekly instalments in Julian Harney’s Red Republican. ‘A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe’ is her rendering of the first sentence of the Communist Manifesto, usually translated as ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism’, which is more concise and accomplishes in a single sentence what she did in two. Her second sentence continues, ‘We are haunted by a ghost, the ghost of Communism.’ ‘Hobgoblin’ contrasts with ‘spectre.’ The latter was formed from the Latin verb ‘to look’ and played an important role in Epicurean philosophy, the subject of Karl Marx’s doctoral dissertation. ‘Hob’ came from the nickname of a country fellow going back to the middle ages, and ‘goblin’ derived from the name for a mischievous sprite or demon. Etymologically, ‘spectre’ is classic and ‘hobgoblin’ is gothic; one refers to philosophy, the other to agrarian folklore.

In his helpful, informative introduction David Black shows what ‘hobgoblin’ meant to the American transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson (‘a foolish consistency […] of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines’) and what it meant to the English utilitarian, Jeremy Bentham (‘anarchy which tremendous spectre has for its forerunner innovation’). He paraphrases the gloss provided by Manuel Yang who sees it as ‘earthly spirit that directly haunt the peasant imagination.’ Thus it can be seen as an antecedent to the post-Hiroshima folk-belief of Godzilla! To these speculations we can add a further source.

Image: Francisco Goya, Duendecitos, (Hobgoblins), etching, 1799

Macfarlane's choice of the word ‘hobgoblin’ owed something to the Protestant English hymn by John Bunyan appearing in the second part of Pilgrim’s Progress. Its third and final stanza goes like this,

Hobgoblin nor foul fiend

Can daunt his spirit,

He knows he at the end

Shall life inherit.

Then fancies fly away,

He’ll fear not what men say,

He’ll labour night and day

To be a pilgrim.

What is the relationship between a communist utopian ideal and the secular humanism? Couldn’t the answer be found in America where both proletarians and pilgrims migrated during her life-time with such hopes and ideals? No, she said. About America there were two ‘very disgusting facts.’ ‘American negro slavery and American exclusion of white women from the exercise of all political, and many social, rights.’ One hundred and fifty years later these facts have been modified in some ways but otherwise remain as disgusting as ever. True valour urgently needed.

Peter Linebaugh, an historian currently residing in the region of the American Great Lakes (‘the fresh coast’), grew up amid the hopes and rubble of post-war London, was schooled by (among others) a wise woman of Appalachia, U.S. Marines in Bonn, Anglicans in Karachi, Quakers at Swarthmore, and Cold Warriors in New York. Later he worked with E.P. Thompson at the Centre for the Study of Social History at the University of Warwick to learn the art and craft of ‘people’s remembrancing’ which has taken printed results in Albion’s Fatal Tree, The London Hanged, The Many-Headed Hydra, Magna Carta Manifesto, and Stop, Thief! He’ll be speaking on 15 June 2015 on Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest (smaller) in Lincoln Castle where the bigger charter has been protected and preserved for 800 years. He’ll be speaking in the castle’s former prison gallery where they used to do the hangings by means of the 'long drop'. Welcome all!

Info

David Black (ed.), Helen Macfarlane: Red Republican: The Complete Annotated Writings, including the first translation of the Communist Manifesto, with an introduction by David Black, (London: Unkant Publishers, 2014).

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com