Slack, Taut and Snap: A Report on the Radical Incursions Symposium

Where the recession opens up ‘slack spaces’ in the city, squatters and artists are sure to follow. Nowadays the apparatchiks of culture-led regen are hard on their heels. But what would a gentrification non-compliant occupation look like? Peter Conlin reports from St. Martin’s Radical Incursions symposium

I spent a lot of time talking with young cultural workers about grassroots, bottom-up efforts. Those are the people I most resonate with, and they’re the people who most desperately need to be heard. This idea of cities rebounding - it doesn’t happen from the top down. It’s almost all organic, community-based.i

Richard Florida, Professor of Business and Creativity at the Rotman School of Management

It has often been observed, both in artist-run milieus and in the mainstream press, that there is a correlation between economic decline and the increase of self-organised cultural activity. But we should wonder – this doesn't appear to be a recession like any other, therefore could self-organisation be re-articulated? On June 25th the Radical Incursions symposium was held at the Innovation Centre Gallery at Central St Martins. The event was framed as an enquiry into the incorporation of squats and other kinds of 'slack spaces' in the current economic climate. The organisers used the post-1989 Berlin term Instandbesetzen – meaning to occupy and renew – to describe the integration process of autonomous occupations into liberal institutions, and to ponder in what ways such a process operates in the UK. The event was organised by Communication and Curation students at Central St. Martins, and featured 'talks and interactions from practitioners and industry experts.' Though rather poorly attended, it was nevertheless one of the few public events on cultural self-organisation since 'the crisis'.

Image: Carefully guarded creativity by mdumlao98

The symposium picked up on the recent interest in informal occupations linked to the term ‘slack space movement’ coined by The Guardian's Robert Booth. The term is endemic to the mainstream media's interest in marginal, 'underground' art activities (such as the coverage of the squatted DA! Gallery in Mayfair). The use of the word 'movement' is over-excited, and slack, as in slacker, is a typical reference to 'edgy' cultural experience. But by titling the symposium 'Radical Incursions,' and introducing references to autonomous occupations and more fundamental challenges to existing relations, we are forced to make a distinction between the radical and the slack. Consequently, the projects discussed in the symposium – most of them self-organised visual arts projects – would be more aptly characterised as slack.

Also, extrapolating from the title, we could wonder if the radicality here refers to an intervention by the market and the state into informal, un-codified activities, or the other way around. That is, exactly whose radicality is this? Considering that one in six shops will be vacant by the end of the year, are there ways to occupy space that are tenably radical from a grass roots perspective, and which would be more than mere incursions?ii

Considering the unprecedented blackmail-bailouts by some of the most powerful financial institutions in the world, the steepest decline in the UK economy since the 1930s with a cumulative contraction of 5.7 percent in the past five quarters, the unprecedented, profound crisis in the global credit system and the incredible socialisation of risk – something drastic and fundamental has occurred.iii There is an understandable tendency, and in fact enthusiasm, for artists and intermediaries to seize upon the positive sides of this 'cultural bear market'. Thus it's not a downturn so much as a time for more unlikely ventures to play the long odds, which may pay out, one day, in whatever mixture of economic and symbolic capital. 'Recessions are awful but can be a good time for artists as creative ideas start appearing while otherwise redundant people are sitting at home fiddling.'ivThe danger with this habitual fondness for seeing the limits of the recession as an opportunity is that it normalises the failures of capitalism, depicting decline as growth.

From within London’s contemporary art scenes there is a kind of knowing familiarity with the cycles of cultural activity dictated by 'economic slumps'. I wonder to what extent such nonchalant acceptance of economic determinism overlaps with the way most artists have sleepwalked their way through the realities of gentrification. At the Radical Incursions symposium Mark Irving, a lecturer at St. Martins, outlined the process by which artists' lofts became yuppie condos in New York from the late 1940s through to the 1990s. These legendary topoi of New York's postwar bohemia provide a very influential template for gentrificaton by which communities were displaced and most artists priced out. But for how long can the process of moving from abandoned, experimental spaces (slack) to luxury real-estate (taut), even for new generations entering into the cultural field, repeat itself with renewed innocence and surprise? If the various players know their lines already, is it possible to move from knowingness to active dissent? Irving wondered whether questioning the destructive nature of gentrification is even meaningful now, and if such an 'ideological concern' is itself outmoded. Today, considering the very strong ideological forces at play, the real questions are why do such post-ideological views persist, and why do artists continue to act against their own interests?

Image: Inside the Da! Collective art squat, 2008 by Mike Williams [http://www.ravishlondon.com/exhibitions/mikewilliams/ ]

This gets at larger issues related to the division of labour between the cultural and the political as they have been conventionally defined, and related to middle class interests which dominate contemporary art. Accordingly, artists, eschewing anything instrumental or programmatic, can only ever ride a wave rather than intervene in a current, and thus their political agency is restricted to dependent relations and limited to their expertise in visual forms and symbolic processes. During the symposium Jason Dungan and Maria Zahle, organisers of The Hex Project Space, exemplified this division. They astutely pointed out that unlike artist-run activities in 1980s and early ’90s that responded to a lack of exhibition spaces, there is no longer the need for more conventional exhibition spaces in London – there are so many here, and they allegedly do it very well. So could artist-led activities move in a new direction? Avoiding anything to do with political action, intensified by the pressures of social inclusion policies and the stigma of political art as social work, these organisers instead look towards a reinvention of arts residencies, artist-led experimentalism and organisational intimacy. A retreat from society to re-imagine possibilities doesn't sound like much of an incursion. Once again, this shows artists are subject to socio-economic processes but don't want to engage with them politically for fear of betraying art.

I find myself in the awkward situation of thinking that it is patently silly to expect oppositional, anti-gentrification politics from cultural self-organisation, yet at the same time realising it is mistake to see artists as oblivious and inactive in anti-gentrification struggles. Many artists at the symposium, and in general, want out of the 'regeneration' loop. However many more are in the ambivalence of not wanting to take part in gentrification, yet not wanting to resist it either. Rachel Anderson, a member of staff at Artangel, expressed concern about artists being pawns in a development game which doesn't serve their interests. Mat Jenner, an organiser of SPACE studios, sees the procurement of permanent, affordable resources for artists as a way to avoid gentrification cycles. From a certain point of view it seems artists shouldn't have to be at the mercy of this system, unless of course they want to be. The Arts Council, developers, politicians, industry experts and Richard Florida are all looking to them. Are they in fact holding the cards? It seems beyond the realm of possibilities, but what would refusal look like?

One thing it wouldn't look like is the 'The Town Centres Initiative' originally announced by Hazel Blears, and the parallel programme developed by Arts Council England. The Arts Council plan is devised to 'help reinvigorate ailing town centres by enabling vacant retail space to be put to alternative uses.'v But, as was evident from Andrew Brown's (Senior Strategy Officer, Arts Council England) presentation at Radical Incursions, the Arts Council programme functions as a way to advertise property and subsidise landlords, 'plastering-over the failures of capitalism', as one audience member put it. Although Brown asserted that previous projects of this kind 'have all demonstrated that occupation by artists is beneficial to the value of the property', he nevertheless stressed that decisions are driven by 'artistic excellence'. It is quite incredible to see the shift from the Arts Council England's 2004 market celebration of the Taste Buds initiative – sub-prime loans to help develop incipient art markets – and Arts & Business projects with the objective of marketising arts organisations, to the The Town Centres Initiative with its role of using art to soften market failure and sell recovery.vi

Concerns were raised at the symposium that this official intervention could interfere with artists' negotiations with landlords, creating an expectation that artists can now pay full market rent. The artists taking advantage of this Arts Council initiative could be seen as anti-squatters, similar to the Camelot Property company which markets to young 'creatives' to pay rent on dilapidated flats in order to keep them from being occupied by the wrong people.vii A similar incorporation dynamic was researched by the INCITE! collective on the effect of 'enlightened' support of grass roots activism. They examined the way foundation grants (in the USA) disrupt political action by forcing a redefinition of an organisation's objectives, integrating them into development schemes with the effect of converting political opposition to service provision.viii But it would be argued that art is different, that it turns on an exceptional logic. As one artist remarked in the event – the fact that I can approach a landlord, say that I am an artist and possibly get access to a space says a lot about the potential power of culture. Indeed, but what precisely does it say?

Domination doesn't only lie in the confined workings of large institutions and forms of standardisation, but in the power to frame alternatives and contain opportunities. Difference isn't eliminated but lead and organised. This initiative is a clear attempt to institutionalise activities in disused urban space, and governmentalise potential counter-politics. As always, there is the ostensibly attractive 'take the money and run' option – extracting funds from whatever policy objectives and its ideological wrapping for a subversive purpose. But what does this really entail? With the time spent carefully spinning the proposal (playing the tricky, all too common game of writing with what seems like conviction yet without actually believing in it), convincing bureaucrats, concealing intentions, satisfying various stipulations, all for a couple of grand (should you be able to run clear), would it really be worth it?ix

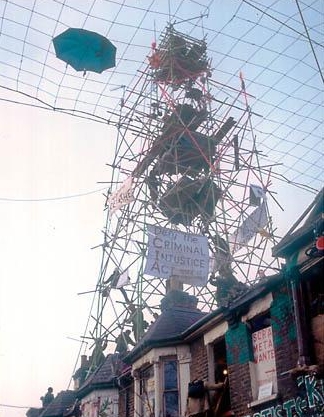

Image: Tower at a Stop the M11 squat on Claremont Road, Leytonstone, 1994, designed to prevent un-radical incursions

Andrew Brown also spoke, adopting 'crime magnet' rhetoric, of the terrible menace of vacant buildings: ‘Anyone who has lived beside a derelict tower-block knows that behaviour changes as soon as it is cleaned up.’ As much as Brown wants to see this program as just an advantageous coincidence of social policy objectives with the Arts Council's dedication to artists, it is actually a true convergence of moral-panic middle-England with cultural disinterest and socially engaged art. Artists putting empty spaces to 'good use' not only subsidises landlords and helps build a green shoot image in the mass psychological game of 'recovery', but also plays a role in setting a positive example within disadvantaged communities. Judging from Brown's account and various Arts Council England documents, the programme is a way to allow the creativity and initiative of artists to raise the aspirations of people in economically depressed areas, and fits nicely with the recent Milburn report on social inequality.x

The symposium ended in an odd way with a more or less collective expression of frustration and desire for ways to resist the co-optation of slack spaces. Art Monthly editor Patricia Bickers made impassioned pleas for the re-invention of public funding and public ownership. There seemed to be a shared contempt for public institutions acting like brokers for private finance initiatives. Simon McAndrew of DA! Gallery attempted to move beyond frustration by trying to orchestrate the creation of a new squatted space. Although moving beyond lament and conjecture, the chances of an art squat attempting to counter these systemic problems are minimal.

The fact that Radical Incursions was situated in an Innovation Centre serves perhaps as an auto-critique. There was almost no-one on the panel or in the audience involved in social centres and infoshops. I assume this was because of the way the event was, predictably, couched in industry friendly language and requisitely ambivalent. Tellingly, the industry experts didn't show up either. But the strange ending to the symposium and the profundity of the financial crisis point elsewhere – to defiant self-organisation and vehement contestations of value. The seemingly inevitable loop from slack to taut and back again demonstrates what happens if finding slack spaces results wholly from the accidental failures of capitalism. Breaking this loop, rather than looking for loopholes, surely involves a fundamental re-articulation of culture in the process of undermining and redefining existing social relations. The lush promise of self-organisation in the aftermath of an economic crisis lies in this destabilisation, rather than the simple pursuit of silver-lined opportunities or lifestyle squatting. The real direction is, as contradictory as it sounds, to actively produce slackness – relations free from career hedging, managerialism and policy impositions, affording time and space for all.

Peter Conlin <endemic AT gmx.com> is a researcher living in London and is a post-graduate student at Concordia University. He is member of the rampART social centre collective

Footnotes

i Murray Whyte, 'Critics on the left a relief, Florida says,' Toronto Star, 27 June, 2009, www.thestar.com/Article/657407

ii Statistic from the data company Experian, cited in Robert Booth, 'Artists' creative use of vacant shops brings life to desolate high streets,' The Guardian, 8 February, 2009, www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/feb/18/slack-space-vacant-shops

iii Paddy Allen and Nick Mead, 'The Ups and Downs of the UK GDP', The Guardian, Friday 24 July 2009.

iv Robert Booth, ibid.

v Arts Council England, 'Action on recession', 2009.

vi For more information on Taste Buds see Anthony Davies, ‘Basic Instinct: Trauma and Retrenchment 2000-04’ in Mute, Vol 1 #29, Winter 2004, http://www.metamute.org/en/Basic-Instinct-Trauma-and-Retrenchment-2000-4

vii Matthew Hyland, 'Embedded Adventurism', Mute, 2007, www.metamute.org/en/Embedded-Adventurism

viii INCITE!, The Revolution will not be Funded, Boston: South End Press, 2007.

ix According to Brown, grants would be between £1000-10000 with most below £5000.

x 'Unleashing Aspiration: The Final Report of the Panel on Fair Access to the Professions', 2009, http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/227102/fair-access.pdf

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com