Signatures of the Apocalypse

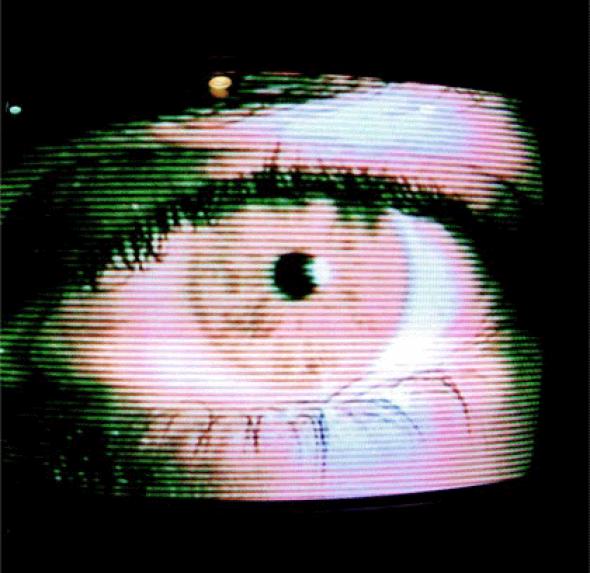

Shuddhabrata Sengupta examines India’s surveillance society, and traces the history of its repressive state apparatus. Is the increased tendency towards a regime of biometrics and a rhetoric of social exclusion a human rights disaster in the making? Photographs by Monica Narula

Apocalypse has a signature: a human shadow imprinted on a wall. The body attached to the shadow has vapourised. A macabre photographic accident somewhere on the streets of Delhi, watched over by too many surveillance cameras, a Hiroshima shadow-image on the masonry.

The signature of the apocalypse, in reverse. Held up to the scrutiny of the afternoon light on a street corner, for the gazes of passers-by, as a reminder that the camera could be everywhere, anywhere. Present not just discreetly on the lamp-post, not just attached with brackets to the surface of walls, but also inside their heads (like so many cyclopean homunculi), or perched, craning their bird like necks on their shoulders, swivelling slightly to take in some new detail.

Delhi, the city where I live, has the unfortunate distinction of a haze that sits on it for most of the year, barring a few blessed days of rain. On most days, this haze makes the whole city look as if it were already a part of one unending length of grainy surveillance video footage. The city’s inhabitants are fleeting images, a mass of blurs on cameras, an expanding codex of an apocalypse practicing its signature. Fleeting images in a city given to foraging for people to be delivered up to the headlines as ‘traitors’, ‘terrorists’ and ‘troublemakers’. Their smudged identikit photographs are emblazoned on cheap newsprint posters, with promises of reward, and exhortations to the citizenry to turn them in at railway stations, bus stops, toilets, cinemas, milk booths. This database of accumulating anxiety is distributed across the walls of the city at random, perhaps in keeping with some unknown cartography of constant caution.

As the capital of a nation state that possesses nuclear arms and has fought four wars with a neighbour that also possesses them, Delhi is accustomed to a consistent level of low intensity panic. This is best characterised by the Indian state’s description of the ‘situation’ as ‘tense, but under control’. Delhi has dealt with the ever-postponed apocalypse by rehearsing the destruction of its own soul, little by little, each day, sinking deeper into a quagmire of secrets and disclosures. We are told not to trust strangers, to report suspicious objects and loiterers, to be wary of abandoned objects that might contain explosive devices, to look under our seats in buses and cinemas for bombs, and to verify the antecedents of tenants and servants. We are instructed in every detail of our paranoia via enthusiastically anxious public service messages. Islamabad, Delhi’s mirror to the west, no doubt has its peculiar parallels, its own special everyday apocalypse of secrets, lies and disappearances.

THE PRESENT TENSE

Today’s India has the world’s largest number of mega cities, and approximately 40 percent of the billion strong population is urban. These huge numbers of people live and work in an intensely technological environment, where several generations of technology, (from steam to silicon) co-exist in an extremely complex industrial ecology. As software and media industries, data outsourcing, information technology enabled industries and the military industrial complex (and the extensive science and technology apparatus attached to it) take centre stage in contemporary India, technology, information, databases and surveillance are beginning to emerge as primary issues that shape the political scene.

This foregrounding of electronic surveillance has filtered into the Indian public imagination, with police phone taps on cricket players and ‘match fixers’ in a betting scandal (April 2000). Subsequent events, like arrests of teenage ‘hackers’ and disgruntled employers interfering with the computer systems of people who owed them money, have punctuated swathes of legislation, including provisions to snoop on computer files and monitor internet use in cyber cafÈs to combat ‘subversion’, ‘piracy’ and ‘pornography’. Media events played their part in giving info-politics a new shine. The Tehelka news portal, for example, attempted to make a front page story of senior state figures caught on camera accepting bribes from undercover journalists (March 2001).

‘Hacking’, ‘Phone Taps’, ‘Hidden Cameras’, ‘Cyber-Security’, ‘Encryption’ and ‘Terrorism’ began to occupy the same vague semantic space in the headlines and the news bulletins against a background of paranoia about ‘terrorism’ in the wake of September 11 and the attack on the Indian parliament in Delhi on 13 December, 2001.[1]

Business for the security industry and what is known as ‘the intelligence community’ has never been better. Surveillance camera sales are booming: 500-1000 units per month are being installed in Delhi alone, 60 percent of them by the Government of India.[2] There is a mushrooming of private security agencies, hi-tech perimeter security systems, and a sudden spurt in public interest in subjects such as biometrics, DNA fingerprinting, forensic electronics, digital video manipulation, face recognition software, voice print analysis and a national citizens database. Watchful eyes and alert ears are everywhere, from the privacy of people’s bedrooms, to buses and public places to cyber cafes, cinemas and telephone booths. There are forms to be filled out, like the one that the police now maintain, containing information about servants, vendors, tenants, people of ‘unstable habitation’ and others that one cannot be certain about. The form for registering servants, for example asks for ‘the servant’s favourite ditty’ and his/her ‘pet words of speech’ as well as the mandatory, name, fathers name, identification marks and so on. Someone somewhere in the maze of the Delhi police is compiling a remarkable database.

Thousands of people still disappear routinely in India. Today, they disappear in Kashmir, as they did in Punjab in the ‘80s, in West Bengal in the ‘70s, and in several states of the North East for the past 50 years.[3] The midnight knock is not – as newspaper editors would like to believe – just a forgotten bad dream from the emergency of 1975-77 when, under Indira Gandhi, basic rights were suspended. It is the everyday reality of a freshly legitimised ‘war against terror’. The policy of preventive detention is backed by several interlocking pieces of ‘extraordinary legislation’: the Prevention of Terrorism Act, and the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. The video tape, the hidden microphone, the intercepted phone call, the thumb impression, the signature, the blood sample, the photograph, the forged confession and the overheard conversation are as effective as weapons, prisons and instruments of torture. Information and secrecy can be used to incriminate, imprison and terrify far more economically than the heavy hand of coercion and violence. People are kept under control with the implied threat of violence. As long as it gives the impression that everyone and anyone is, or can be, suspect and under watch, the machine does not necessarily have to work efficiently (as indeed it cannot).

In this respect, India is not exceptional: the United States or Britain, top cops of the new world order, are probably just as prone to info-policing; Russia, France and Italy, just as labyrinthine in terms of secret agendas and special interests dictating policies; China, Cuba, Iran or North Korea, just as lethal. What is special about the state’s ability to function as it does in India is a certain public complacency. National civil society denies what the Indian state security is doing, partly, because it is so disturbing to countenance, and partly because of a weak understanding of the importance of privacy in an open society, and a smugness about the sanctity of ‘democratic institutions’. This creates a perfect climate for a wholesale assault on civil liberties in the name of ensuring order.

All of this, given a certain gloss of nationalist aggrandisement and the rhetoric of ‘national security’ ensures a continuation of the order: the massacres and the disappearances continue. Beyond a certain point, nothing is questioned.

THE BIRTH OF SURVEILLANCE CULTURE

There is nothing new about surveillance in India: governments have fallen on the issue of tapped telephones before, at the centre of the country, as well as in the states. But the last five years or so have seen computers, the internet, mobile phones, video footage, and sophisticated databasing techniques become central to the political imagination. The state sees control over information, and the technologies of communication as one of the keys to power.

The building of the ‘Research and Analysis Wing’ (RAW), India’s CIA, is the same dusty beige of the summer haze itself. In the winter, the haze turns a thin grey, but the RAW building still manages to blend in. It is a giant spider with a clever evolutionary camouflage adaptation; only the thin fibrous antennae on its head give it away as the watchful, lethal creature that it is. It sits at the centre of the Indian state’s expanding web of surveillance systems, intelligence and security agencies (RAW, DIA, IB, CBI, CID, DRI, MI, SSB, NSG, CRPF, BSF, ITBP, SSB, SSF, CISF etc. – a shadow alphabet), information processing systems and a formal (as well as informal) network of knowledge and power that stretches from the cabinet secretariat to the street corner tea shop in cities, small towns and villages. This web is powerful precisely because so little is known about it. Though it wants to know everything, it is shrouded in mystery, accountable to nothing and no one.

RAW was born in the corridors of power, the imperial capital that Edwin Lutyens and Robert Baker built in New Delhi. Its functions and exact powers are cloaked in the arcana of the ‘Official Secrets Act’, which, like most legal devices in India, is a legacy of colonial rule. The rulers in Delhi, who preside over the second most populous country in the world, perceive themselves as inheritors of the imperial mantle of the Mughals, and of the British Empire in India, conquering Hindu heroes and Buddhist emperors all rolled into one. They cocoon themselves in a mantle of secrecy and a network of informer-driven paranoia. Ardent students of one of the earliest Sanskrit texts on statecraft – Kautilya’s Arthashastra (which Foucault would have delighted in) – they see secrecy and covert knowledge as the fluids that animate the capillaries of power. As the British Raj knew well, and as every Sultan of Delhi learnt if he wanted to stay on his throne, the informer and the spy are great assets to a repressive state; but its most insidious instruments are the suspicions that pit subject against subject through the subtle play of rumour, blackmail and secrecy.

THE PREHISTORY OF AN APPARATUS

The surveillance systems that lie at the heart of the modern state’s project are closely interwoven with the history of South Asia. Fingerprinting, the first scientific forensic identification technique to have proved successful, was initiated by William Herschel in India in 1858 and was perfected and systematised by Edward Henry and Azizul Haque of the Bengal Police in 1893.[4] Anthropometrical data, in the form of cranial radii, nasal indexes and finger length, were tested for their utility in developing the science of criminology, often aided by an ethnographic discourse that constructed an elaborate taxonomy of criminal tribes, deviant populations, and martial races. The colonial state kept detailed records of political intelligence on so-called subversive activities that entered every domain of life. Informers were cultivated in the criminal underground, in the postal department, amongst railwaymen, soldiers, political activists, trade union members, lawyers, prostitutes, clerk, thieves, teachers, workers and students. Under the Indian Telegraph Act, newspapers, journals, libraries books and letters, street corner conversations, cafe gossip, speeches and underground literature were scrutinised.

The records of censorship, observation and punitive action can be traced in the meticulous archives of the India Office in the British Library. A powerful machine, at work over almost nine decades from 1858 right up to the transfer of power in 1947, is revealed in gazetteers, census records, official orders, notifications and correspondence, along with the indices and codices of the intercepts of the intelligence wing of the state political departments, military intelligence, censors’ reports on letters written by Indian soldiers in the Great War, catalogues of proscribed publications, albums of personal letters and telegrams, photographic studies and maps.

The techniques of surveillance, identification and repression learned in the colonies went on to be perfected in London, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Belfast. Identification by fingerprinting, or the use of photographic records for policing purposes began to be used as measures of control, and were popularised through spectacular feats of ‘detection’ that helped solve a spate of notorious acts of criminality. They became the instruments used to deal with restive populations, particularly the vast numbers of the urban underclass. Who were these first objects of the gaze of power? The indigent, the inmates of prisons and workhouses, the insane, the sexually deviant, workers, the Irish, demobilised conscripts, aliens, exiles and immigrants and other potentially troublesome segments of the population. ‘Technological’ advances and innovations in the specific fields of technologies of control and surveillance and in the arena of the politics of information, flowed from the colonies back to Britain. In this instance, colonialism sapped the liberties of the common people of Britain as much as it worked as a repressive power in India.

THE PREHISTORY OF SECRECY AND POWER

The state machinery of Independent India reinherited this apparatus and refined it still further.[5] It became firstly a means of control over the means and politics of information and communication, maintained through successive legislative instruments specifically designed to deal with information ranging from the Indian Telegraph Act (1885) to the Information Technology Act (2000) and the Convergence Bill (2001). Secondly, it worked as a legislative sanction for the state to act covertly and in secret, as per the provisions of the Official Secrets Act (1923), only very weakly challenged by the recent Freedom of Information Act (2002), which continues to obscure vital areas of public concern like defence expenditure and policy and anything deemed in the ‘national interest’ under a cloak of secrecy. Thirdly, a plethora of laws, rules and regulations enforced ‘reasonable’ restrictions on the freedom of speech under the ubiquitous rubrics of ‘national interest’ , ‘territorial integrity’ and ‘the sovereignty of the republic’, along with public order, decency, the dignity and authority of the judiciary, and relations with friendly states. Finally, a series of extraordinary laws like the Prevention of Terrorism Act (2002) now allow for preventive detention and interception of communications, enabling the state to admit confessions made in custody as evidence, and to compel those accused under its provisions to furnish biological information as evidence.

Today, attempting to find out what the state is doing may itself be a crime, a violation of ‘official secrecy’; an attempt to communicate what the state is doing or protest against it may invite censorship provisions in the national interest. This forms a lethal circuit of secrecy, in which people disappear or face long prison sentences on trumped up charges. The fear of certain consequences are means enough to keep most people quiet, most of the time. Meanwhile India, like the United States, continues to trumpet its status as a functioning democracy, and like the United States refuses to ratify the international convention against torture or the international agreement for a criminal court.

THE TERROR OF THE SURVEILLED

While threats to public security from terrorist organisations undoubtedly exist, the climate of secrecy that surrounds so-called anti-terrorism operations makes it difficult to believe that the state does not resort from time to time to infiltrating, manipulating, or even creating ‘terrorist’ groups to generate escalating episodes in the shadow-war that is used to justify all sorts of repression. (Italy’s dubious record in engineering ‘terrorism’ in order to justify a wave of repression in the 1970s, and the double games played by British Intelligence Agencies in Northern Ireland, spring to mind as recent analogues.) Judging by the rising graph of fake ‘encounters’ (actually extra-judicial executions) which accompany so called ‘terrorist incidents’ timed perfectly to coincide with general political crises, the climate of secrecy is instrumental in allowing the Indian state to pursue its dubious dual agenda.

As if in response to the demands of a ‘B’-movie script, the bodies of slain terrorists (including those taking part in so called suicide attacks) obligingly yield diaries, mobile phones, identification cards, and electronic and forensic trails that lead to laptops, to phone conversations, and other elements of information that invariably fall into place; as if well-trained terrorists were waiting to have themselves blown up or be shot only in order to enable this harvesting of information. Lethal midnight raids in the suburbs of Delhi by police commandos (as with a young man identified as ‘Abu Shamal’, a ‘Kashmiri’ militant said to be involved in the attack on Delhi’s Red Fort in December 2000, who upon the arrival of his grieving parents from nearby Uttar Pradesh was found to be neither Kashmiri, nor a militant) are prompted by informers’ reports about someone frequenting a cyber cafÈ too often, or by someone’s email containing the ‘wrong’ sort of attachments.[6]]On other occasions, the DNA records of dead people considered to be terrorists are found to be deliberately tampered with, as in the case of the encounter killings of the so-called terrorists behind the Chattisinghpora massacre during Bill Clinton’s visit to India in March 2000.[7] Such interventions confuse even the identities of corpses. (In this case, the corpses designated as ‘terrorist’ were those of innocent Kashmiri villagers who were killed by security forces. Someone, after all, had to be seen to have paid the price for the Chattisinghpora incident.)

Last year, the undue haste with which the trial of the four accused in the ‘Parliament Attack’ case under the Prevention of Terrorism Act was conducted left many disturbing questions unanswered. Particularly disturbing was the meting out of a death sentence at the end of first phase of the trial to SAR Gilani, a Delhi university lecturer in Arabic who happened to be a Kashmiri Muslim, on the basis of the mistranslation of an illegally obtained mobile phone intercept left many disturbing questions unanswered.[8]

Why, for instance, was there such a pressure to establish a ‘conspiracy’, something that could be done only by implicating Gilani, and glossing a conversation between him and his brother about domestic matters as a discussion of the terrorist attack on the parliament? Was this because it became necessary to create a series of justifications for the war hysteria and extraordinary military build up that happened at the border right through the summer of 2002?Why was it necessary to spread dis-information in the press about SAR Gilani’s assets in Delhi, and clumsily try and twist his friendship with a Jordanian student into shady contacts with Arab terrorist networks?

Why was it necessary to browbeat and threaten a section of the electronic media not to carry any statements by SAR Gilani’s co-accused that he had nothing to do with the attack on the parliament?Why was it necessary to try and obtain forced confessions from Gilani and, on failing to do so, have him attacked by fellow prisoners in Tihar jail?

Why was it necessary for the trial judge to cast aspersions on the motives of defence witnesses, and digress unnecessarily into lengthy expositions on matters completely unrelated to the case? Was the judge attempting to shield the prosecution’s inept attempts at forging evidence?

All of these questions remain unanswered. When the defence appealed against the quality of evidence brought forth by the prosecution in another case, something dramatic needed to be done to boost the public image of the special cell of the Delhi Police behind Gilani’s arrest. A convenient opportunity presented itself shortly before the closing arguments in the first phase of the trial were to be made. The special cell of the Delhi Police (notorious for its ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ policy) was able to add yet another spectacular encounter to its already distinguished record. Two supposed terrorists, apparently intent on a massacre, were shot dead on the eve of the Diwali festival by men of the special cell who had been shadowing them in the underground parking lot of the Ansal Plaza Shopping Mall, in the elite southern district of Delhi. A day later, an eyewitness (a medical practitioner) came forward to say that he had seen two injured or drugged but unarmed young men, being taken out of a car by what appeared to be plain clothes policemen, made to walk some distance in the underground parking area, and then shot in cold blood with automatic weapons.[9]

The special cell mounted what amounted to a veritable ‘psy-ops’ style campaign against this eyewitness. It once again came up with mobile phone tracking records purporting to show that the eyewitness could not have been in the basement parking lot, when the ‘encounters’ took place. The eyewitness’s appeal for independent verification and inquiry into the incident, the tracking records of his mobile phone, and covert attempts at slander and character assassination, amounted to nothing, and the media rapidly lost interest in his story. The ‘heroic’ role of the special police cell was rediscovered. The vigilant team of defence lawyers and human rights workers who were beginning to be able to pick many holes in the prosecution’s weak arguments, suddenly found themselves up against heroic policemen who had saved a city from yet another terrorist atrocity. It would be jejeune to think that the passions generated by the reported acts of heroism in the media, and the clever manipulation of the actual truths of the Ansal Plaza shootout incident had no bearing on the course of the trial of SAR Gilani. Eventually, he and three of his co-accused, were handed a death sentence. The case has now gone to a higher court for appeal where SAR Gilani is being represented by the prominent lawyer and former law minister Ram Jethmalani. There are some hopes that a combination of the recent attempts by the state to appear ‘softer’ on Kashmir, and the embarrassment of too obvious a ‘show trial’ with evidently manufactured evidence might be a factor persuasive in the delivery of a favourable verdict and SAR Gilani may yet be acquitted (or at worst receive a lighter sentence). But it is too early to say this with any confidence.

In another trial, involving another person called Gilani, (Iftikhar Gilani, no relation to SAR Gilani) a Kashmiri Muslim journalist based in Delhi, the Official Secrets Act was invoked with a degree of complacent Èlan.[10] The arrest was televised on all major television networks as a breakthrough. Iftikhar Gilani spent several months in Tihar Central Prison, where, as a so-called ‘traitor’, he was subjected to a variety of humiliations, both by other prisoners, and by the prison authorities. Outside the prison walls, a trial by media took place: every official press release about the case was faithfully printed. The charges against Gilani were based on a raid on his house and a search of his computer, which was said to yield ‘classified’ documents. These documents included research articles from an online journal freely available in print form at university libraries in Delhi and press releases from a political organisation active in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (the so-called ‘Balwaristan National Liberation Front’) which, being against Pakistan’s control over ‘Azad Kashmir’, would normally be considered to be a pro-India outfit. In a peculiarly Kafkaesque travesty of justice, Iftikhar Gilani was accused of being a separatist sympathiser because of the presence of these documents in his computer. After a concerted public campaign by Iftikhar’s journalist colleagues, the false charges against him were dropped and he was freed, but without any expression of regret or even a formal apology.

Gilani found he was not the only victim of the Official Secrets Act in prison. There were many others like him, 28 in Tihar Prison alone, mostly held on charges far more flimsy than his.[11] All were arrested after the attack on the parliament, when security agencies seemed to have gone into overdrive. Several were accused of possessing a single incriminating ‘classified’ document, a hand drawn ‘map’ of Meerut Cantonment consisting of a line, a rectangle and a few place names. After they had been tortured and intimidated into making a confession, this so-called map would be planted on the accused and presented to the magistrate as ‘evidence’ of espionage. Almost invariably, the accused would be Muslim men.

SAR Gilani and Ifikhar Gilani and their families have both had to deal with months of harassment, intimidation, uncertainty and agony. While Iftikhar Gilani is now free and back practicing journalism, SAR Gilani still lives under the shadow of a death sentence. In a sense, both had brighter chances than most under their circumstances. They are educated, middle class professionals with a wide network of family, friends, acquaintances and well wishers who could campaign on their behalf, set up defence committees, arrange for competent and committed lawyers, speak to a hostile media and take public stands (in the case of SAR Gilani, tirelessly, but unfortunately still unsuccessfully, and in the case of Iftikhar Gilani, with notable success, although without any recompense from the state). Unfortunately, the majority of people who find themselves at the sharp end of the security apparatus in India have neither the social network, the political capital, nor the personal wherewithal to withstand the relentless assault of the state, in or out of prison.

INCLUDING ‘OTHERS’ OUT

Perhaps the most disturbing developments arising out of the mania for surveys in India are the current scheme to set up a national citizens database, and the programme for the introduction of biometric citizens identity ‘smart‘ cards. The former exercise will climax in either the National Identification System Home Affairs Network (NISHAN) or the INDIA CARD scheme, by which all citizens will have to carry identity cards containing identifying photographs, all relevant information (including legal records) about them, and biometric data (body measurements, handprints, etc).[12] The Union Ministry of Home Affairs has commissioned Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), a software consultancy multinational based in India, to do a feasibility study for the National ID card scheme. The TCS report suggests that the whole exercise should be made market friendly, and that the state actually make money out of it by selling information that it gathers about citizens to corporate bodies. This will no doubt be seen as a model mechanism of ‘self-reliant’ state control.

The other proposal – the INDIA Card Scheme – is put forward by a private Bangalore based company (Shonkh Technologies International Ltd.) which no doubt will be a major player in terms of making a bid for the scheme’s execution on an India-wide basis. The Shonkh Technologies website features plans for a 4.1Mbyte laser card which can store ‘details of the citizen from birth to death’, including ‘biometric based information for authentification.’[13] Similar schemes have been tried out already in Thailand, and Pakistan too has had a ‘shanaqti card’ (Identity Card) system for decades. All Pakistani citizens must carry a photo ID card that also states their religion. The hated ‘passes’ in Apartheid era South Africa were basically ID Cards that also mentioned ‘race’. Likewise, the genocide in Rwanda was facilitated by the recently introduced Identity Card system that helped distinguish between Hutus and Tutsis.

The implication of an identity card scheme in India are clear. It is by now well known that in the Anti-Sikh pogroms of 1984, and the Gujarat killings of 2002 for instance were at least partly administered with the help of electoral registers and census records. Computerised ID card systems would make such exercises that much simpler and more efficient. It would tally with attempts by such as the Bharatiya Janata Party government of Gujarat, already tainted by its association with the organised massacre of Muslims last year and several incidents of intimidation toward its Christian population, to undertake a ‘special registration’ of Gujarati Christians.[14]

The collation of various kinds of information about citizens scattered in various data sets within a single database under the control of the state implies a gross violation of privacy and liberty. For instance, it may enable a person’s confidential medical records (their HIV positive status, say) to become part of a police investigation that is completely unrelated to the issue of their health. But what is even more sinister is the expressly stated purpose to use the ID card system as a means to unleash one of the largest state administered deportation exercises in human history. At a recent national conference of chief secretaries and directors-general of police, the deputy Prime Minister L.K. Advani, while making yet another announcement about the ID card scheme, launched an offensive against foreigners overstaying in India.[15] ‘There is no reason,’ Advani said, ‘why our states should be soft on them. Immediate steps should be taken to identify them, locate them and throw them out.’

The deputy Prime Minister, who is also in charge of internal security as Union home minister, voiced concern at ‘over 11,500 Pakistanis and 15 million Bangladeshis illegally staying in India’ and directed state governments to launch a special drive to ‘detect and deport them, as they posed a serious threat to national security.’

The implications of the state deciding to ‘throw out’ 15 million people it considers to be ‘illegal aliens’ are serious, especially given the fact that Bangladesh displays no inclination to accept them as its citizens. In several waves of ‘deportation’ incidents, ‘aliens’ have been taken in trucks to the no man’s land at the India-Bangladesh border, and asked to run towards Bangladesh. If they do, they are attacked by the Bangladesh Border Rifles; if they try to return to India, they are fired upon by the Indian Border Security Force.

At present, this drive is seeing people in their hundreds being ‘thrown out’ on a monthly basis from the slums of Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata and the border districts of Assam, West Bengal and other states of the North East. With a national ID card system in place, the drive will intensify: the government will have to consider ‘internment camps’ for ‘aliens’ where it can detain the 15 million Bangladeshis it wants to cleanse India of. The urban poor, particularly those with east Bengali or even Bengali accents and the misfortune of having a Muslim name, will have to work very hard to prove their worth as ‘Indian citizens’. Their shacks will be demolished with bulldozers, their livelihoods as rickshaw pullers, garbage recyclers, domestic help and manual labour will be taken away, and they will be made to board trucks that take them to unknown destinations at gunpoint. Distant echoes of Yugoslav ‘ethnic cleansing’ campaigns will make themselves heard on the streets of Indian cities.

This is a human rights tragedy of unforeseen proportions in the making, backed by the Indian state’s technological imagination run amok, a nationalist discourse that values Indianness more than it values humanity, and a complacent, racist ‘civil society’ which believes that the deportation of Bangladeshis is anyway all for the good. The vague worry that it may be our turn to be fingered in the next choreographed identification parade is not enough to stem the tendencies toward this disaster. The surveillance cameras continue to multiply on the streets, the ‘encounter’ deaths continue to accumulate, and surveys of aliens in the slums demonstrate the need for the tragedy that will take place. The apocalypse is practicing its signature, freezing the future’s shadows on to the walls of Delhi.

[1] The following are links to articles giving detailed information on use of surveillance and biometrics in India today:• On phone tapping, privacy and telecom policy in India:‘Time to Ring in Changes’, Sandeep Dikshit, The Hindu, 26 January 2003[http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/2003/01/26/stories/2003012600291800.htm]• On SMS surveillance: ‘India’s Short Message: We C U’, Ashutosh Sinha, Wired [http://www.wired.com/news/privacy/0,1848,56666,00.html]• On SMS surveillance: ‘Update on Indian SMS wiretapping’ [http://vigilant.tv/article/2578]• ‘Stop Cyber Surfer, where’s your ID?’, Leslie D’Monte, ZDNet India, 16 May 2001[www.zdnetindia.com/news/features/stories/22533.html]•‘Everyday Surveillance: ID Cards, Cameras and a Database of Ditties’, Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Sarai Reader 02: The Cities of Everyday Life[http://www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/10infopol/ 04surveillance.pdf]• ‘The Face of the Future: Biometric Surveillance and Progress’, Rana Dasgupta, Sarai Reader 02: The Cities of Everyday Life[http://www.sarai.net/journal/02PDF/10infopol/ 03biometrics.pdf][2] On the prospects of the CCTV industry in India see: ‘CCTV Cameras - International overview – India’, Videocomplex [http://www.cctv-systems.com/CCTV-India.html]. [3] See:• On ‘disappearances’ in Jammu and Kashmir (Amnesty International): ‘If they are dead, tell us’, AI INDEX: ASA 20/002/1999, 2 March 1999[http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/engASA200021999]• Victims’ families file affidavits in disappearances cases in Punjab, by Siddharth Suresh, Indian Express, 5 February 2001 [http://www.indianexpress.com/ie/daily/20010205/ifr05018.html]• The Manipur Update [http://www.geocities.com/manipurupdate/feature_2.htm][4] For a good survey of the history of fingerprinting, particularly in India see, Fingerprints: Murder and the Race to Uncover the Science of Identity, by Colin Beavan, Fourth Estate, London, 2002[5] For a chronology of information politics in India, see ‘A Chronology of the Media and the State’, Jeebesh Bagchi, Sarai Reader 01: The Public Domain[http://www.sarai.net/journal/pdf/127-132/(law).pdf][6] ‘Red Fort breach – Police kill “Lashkar militant”’, Indian Express, December 27, 2000[http://www.indianexpress.com/ie/daily/20001227/ina27038.html]‘Encounter stage-managed? Residents gherao police post’, The Tribune, December 28, 2000[http://www.tribuneindia.com/2000/20001228/main1.htm][7] See ‘Death in Kashmir’ by Pankaj Mishra, an essay on the Chatisinghora Massacre in the New York Review of Books, September 21, 2000 [http://www.nybooks.com/articles/13813][8] See ‘The Worst is Always Precise’, Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Sarai Reader List, December 19, 2002[http://mail.sarai.net/pipermail/reader-list/2002-December/001981.html]For details of the SAR Gilani case, see the following links :• All India Defence Committee for Syed Abdul Rehman Geelani [http://www20.brinkster.com/sargeelani/]•‘Three Sentenced to Death in Parliament Attack Case’, Anjali Mody [http://www.hinduonnet.com/stories/2002121905170100.htm] • ‘Police Misinterpreted Phone Conversation’ [http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/2002/10/12/stories/2002101200711300.htm]• ‘Phone Intercepts Not Admissible Evidence Under POTA:HC’, Nirnimesh Kumar [http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/2002/10/31/stories/2002103106690100.htm]• ‘Timeline of Attack on the Parliament’, Rediff.com [http://www.rediff.com/news/pattack.htm]• ‘Geelani Issues Notice to Hindustan Times, Delhi police’[http://www.milligazette.com/Archives/01072002/0107200281.htm][9] ‘Ansal Plaza Encounter: Delhi Doctor Goes into Hiding’[http://www.thehindu.com/2002/11/08/stories/2002110804580100.htm]‘Witness Alleges Delhi Shoot Out was a Frameup’[http://www.rediff.com/news/2002/nov/05onkar.htm]‘He Was Not Present During Shooting: Police’[http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/2002/11/10/stories/2002111004360800.htm][10] See interview with Iftikhar Gilani in Index On Censorship[http://www.indexonline.org/news/20030120_india.shtml][11] See the four-part story in the Indian Express on the Official Secrets Act:• Nothing Official About These Secrets[http://www.indianexpress.com/full_story.php?content_id=19853]• Pak Fooled with Fakes but OSA Sticks[http://www.indianexpress.com/full_story.php?content_id=19916]• In Custody in Valley but Held Again in Delhi[http://www.indianexpress.com/full_story.php?content_id=19993]• 16 Years After Arrest, a Case Drags On[http://www.indianexpress.com/full_story.php?content_id=20066][12] For more about NISHAN see the following sites:• Dataquest Magazine: [http://www.dqindia.com/content/top_stories/101022206.asp]• The Hindustan Times: [http://www.hindustantimes.com/nonfram/170900/detFEA03.asp][13] For more on the INDIA Card scheme [http://www.shonkh.com/indiacard.html][14] ‘Gujarat Admits Carrying Out Survey on Christians’, Press Trust of India, Hindustan Times [http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/ 181_209280,000900040003.htm][15] ‘Mother of I-Cards’, 5000-cr tag’, Bhavna Vij-Aurora, Indian Express, January 13, 2003[http://www.indianexpress.com/full_story.php?content_id=16574]

Shuddhabrata Sengupta <shuddha AT sarai.net> is a media practitioner and artist with the Raqs Media Collective (see also, Mute 20). The collective is one of the initiators of the Sarai Programme [http://sarai.net] at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi. Their work was exhibited at Documenta 11 and will be seen at the forthcoming 50th Venice Biennale, 2003. Shuddhabrata lives and works in Delhi.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com