A Short History of Performance: Part II

The second season of the Whitechapel's performance art retrospective was dedicated to the pedagogical form of the lecture as a medium for art. While some of the performances satirised the artists' function as commodity and carrier of imperialist agendas, the Whitechapel itself was still upholding the enduring 'cult of the artist'.

Whitechapel Art Gallery's selective revisitation of performance art began in April 2002, showcasing a series of reenactments by artists prominent in the ’60s and ’70s. 'A Short History of Performance: Part I' conceived performance as a 'radical medium that often encouraged audience participation', while neatly excluding reference to the largely uncapturable Happenings which effectively collapsed such boundaries and explicitly rejected the idea of reenactment. This process of forgetting what the gallery cannot accommodate was continued last November with Part II, which limited the concept to the more specific sub-genre of 'lecture-action', that takes the 'pedagogical framework of the lecture ... as a medium of art in itself'. In this spirit, the catalogue was designed as a student notebook, and its introduction referred to the ambitions of Whitechapel Art Gallery's founders (the local vicar Canon Samuel Barnett and his wife Henrietta) to 'empower the public through learning'. That was, however, 1904, and today the institution would be forced to renounce such a paternalistic attitude, and admit that contemporary art 'does not generally aim for explanation' or 'the truth' and only represents 'a process of inquiry'. Instead, as the catalogue conjectures, the educational mission is to be fulfilled by 'artists with the tools of academia'.

Alongside screenings and reenactments of past 'lecture-actions', new work was also presented this time, mostly by younger artists but also notably by Robert Morris (well-known for his minimalist sculptures and his membership in the Art Workers Coalition in the late 1960s). It appears that the curators (Andrea Tarsia and Iwona Blazwick) wanted to avoid recreating the chasm between past and present that had been identified by the audience in Part I, so now the priority was recontextualisation rather than faithful reproduction.

> Andrea Fraser, 'Official Welcome', 2001.............................................One such recontextualisation was Andrea Fraser's 'Official Welcome' (originally performed in 2001) with which she opened the season, taking on the alternate roles of Whitechapel director, curator, several different invited artist personae, and herself. Each artist's persona went through a humiliating confessional strip-show, reminiscent of the yBa's (amongst others’) mythification and role-play ('bad girl', 'talented and traumatised', etc). Effectively, what is sold to the audience is not their art, nor their brand-signature, but their naked body as the site of their supposed emotions, personal history and capacity to produce. Fraser's institutional critique was cruel and bleak, implicitly concluding on the inevitability of creativity's adulteration by the art market, that there is no 'outside', through her own choice of context for her work. Knowingly allowing the institution to demonstrate its openness using her criticism, her disregard for alternatives makes her sound like a desperate scream in the dark.

> Andrea Fraser, 'Official Welcome', 2001.............................................One such recontextualisation was Andrea Fraser's 'Official Welcome' (originally performed in 2001) with which she opened the season, taking on the alternate roles of Whitechapel director, curator, several different invited artist personae, and herself. Each artist's persona went through a humiliating confessional strip-show, reminiscent of the yBa's (amongst others’) mythification and role-play ('bad girl', 'talented and traumatised', etc). Effectively, what is sold to the audience is not their art, nor their brand-signature, but their naked body as the site of their supposed emotions, personal history and capacity to produce. Fraser's institutional critique was cruel and bleak, implicitly concluding on the inevitability of creativity's adulteration by the art market, that there is no 'outside', through her own choice of context for her work. Knowingly allowing the institution to demonstrate its openness using her criticism, her disregard for alternatives makes her sound like a desperate scream in the dark.

> Martha Rosler, 'Semiotics of the Kitchen', video, 1975..............................................A striking parallel to Fraser's performance was Martha Rosler's 'Semiotics of the Kitchen' (1975), a corruption of the TV cookery show format, where the female cook is furious with her kitchen confinement. She demonstrates various alphabetically ordered kitchen implements, although her demonstration does not suggest their orthodox use but their potential to cause pain as she violently directs their blades at the camera or bangs them on the chopping board. At Whitechapel, this work was reenacted by four groups of young women, each demonstrating a different tool in succession while being simultaneously taped on video. This seemed to be a comment on the feminist who, unable to turn theory into practice and transform her everyday social role, dreams of venting her repressed anger while still forced to be a housewife. Such interpretation could have been given when Martha Rosler's kitchen show was shown on daytime television. In Whitechapel, however, the half-hour repetition of kitchen revolt by a series of young women seemed to be making the argument that almost 30 years later women are still confined to their traditional roles and routines, which they have not altered but just expanded, adding to their supposedly voluntary workload, still unable to bring all these accumulated theoretical insights into their daily lives. In Fraser's piece, the performer threatens to attack the structures she finds herself in, just like the televisual image of Martha Rosler seems to be trying to escape from the screen by making symbolic gestures that go beyond it, but remains within it, as the spectacle of a mere protester.

> Martha Rosler, 'Semiotics of the Kitchen', video, 1975..............................................A striking parallel to Fraser's performance was Martha Rosler's 'Semiotics of the Kitchen' (1975), a corruption of the TV cookery show format, where the female cook is furious with her kitchen confinement. She demonstrates various alphabetically ordered kitchen implements, although her demonstration does not suggest their orthodox use but their potential to cause pain as she violently directs their blades at the camera or bangs them on the chopping board. At Whitechapel, this work was reenacted by four groups of young women, each demonstrating a different tool in succession while being simultaneously taped on video. This seemed to be a comment on the feminist who, unable to turn theory into practice and transform her everyday social role, dreams of venting her repressed anger while still forced to be a housewife. Such interpretation could have been given when Martha Rosler's kitchen show was shown on daytime television. In Whitechapel, however, the half-hour repetition of kitchen revolt by a series of young women seemed to be making the argument that almost 30 years later women are still confined to their traditional roles and routines, which they have not altered but just expanded, adding to their supposedly voluntary workload, still unable to bring all these accumulated theoretical insights into their daily lives. In Fraser's piece, the performer threatens to attack the structures she finds herself in, just like the televisual image of Martha Rosler seems to be trying to escape from the screen by making symbolic gestures that go beyond it, but remains within it, as the spectacle of a mere protester.

Fraser's portrayal of the artist could also be compared to that of the corporate employee: they are both performers for whom the progressive 'improvement' of their communication skills is the main aim of their work, and they both allow their capacity to create and communicate (their bodies, desires, affects, sociality) to be marketed, administered and subsumed into hierarchical relations of production. This interpretation could also serve for Carey Young's new work, 'Optimum Performance': a male actor's business speech, staged as part of the season. The artist's stated intention was to make the audience aware of how corporate discourse understands 'performance': the degree of meeting defined qualitative and quantitative targets. In the discussion that followed I expected the artist to talk about parallels between art and business, but instead her focus was on the appropriation of the language of creativity by business discourse. No comment was made about the role of the art market in sustaining the perennial narratives of individual creativity and innovation as the preconditions for the ascription of sign and exchange-value to art objects or performances.

> Joseph Beuys, Lecture-Action at the Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, 1980.........................................The ongoing reign of the individual author and cult of the artist – despite the many attempted coups – was, predictably, also evident on the day dedicated to Joseph Beuys. Films and documentation of his 'Lecture Actions' in the UK from 1972 to 1980, revealed Beuys contradicting his own creed of 'direct democracy' and his celebrated slogan 'everyone is an artist'. He arranged the gallery space so that, even though the public was invited to a participatory discussion, he could talk from a disproportionately high stage, holding a microphone that could overwhelm all other voices. These 'discussions' were mostly about alternative pedagogy and alternative political systems, and were indicative of Beuys' often unelaborated ideas. Gustav Metzger sometimes participated, and his debate with Beuys touched on the question of western culture's responsibility for weapons of mass destruction, while Beuys seemed to have faith in the transmission of western technology to 'primitive' cultures. The symposium on Beuys almost replicated his contradictory politics: it was all about his life, his 'exceptional multifaceted talent', his personality, and his status that could be 'compared to Leonardo da Vinci' as one speaker fervently asserted. As if all creativity only ever emanates from the individual, there was little mention of his social and political context, and that was only used to demonstrate how he was able to transcend it. It was instructive of how the idea of participation can be misappropriated in order to establish authority. In the transcript of one of Beuys' lecture actions one member of the audience shouts: 'Do you realise what you are doing standing up there? Do you realise that we can only hear your voice?'

> Joseph Beuys, Lecture-Action at the Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, 1980.........................................The ongoing reign of the individual author and cult of the artist – despite the many attempted coups – was, predictably, also evident on the day dedicated to Joseph Beuys. Films and documentation of his 'Lecture Actions' in the UK from 1972 to 1980, revealed Beuys contradicting his own creed of 'direct democracy' and his celebrated slogan 'everyone is an artist'. He arranged the gallery space so that, even though the public was invited to a participatory discussion, he could talk from a disproportionately high stage, holding a microphone that could overwhelm all other voices. These 'discussions' were mostly about alternative pedagogy and alternative political systems, and were indicative of Beuys' often unelaborated ideas. Gustav Metzger sometimes participated, and his debate with Beuys touched on the question of western culture's responsibility for weapons of mass destruction, while Beuys seemed to have faith in the transmission of western technology to 'primitive' cultures. The symposium on Beuys almost replicated his contradictory politics: it was all about his life, his 'exceptional multifaceted talent', his personality, and his status that could be 'compared to Leonardo da Vinci' as one speaker fervently asserted. As if all creativity only ever emanates from the individual, there was little mention of his social and political context, and that was only used to demonstrate how he was able to transcend it. It was instructive of how the idea of participation can be misappropriated in order to establish authority. In the transcript of one of Beuys' lecture actions one member of the audience shouts: 'Do you realise what you are doing standing up there? Do you realise that we can only hear your voice?'

Artists' oblivion to the frequent contradiction between their expressed ideas and their artwork was something addressed by Robert Morris's lecture on contemporary American sculpture, 'From a Chomskian Couch, the Imperialist Unconscious'. The notion that sculpture and land art of monumental proportions can be seen as ideological symbols of empire (in a similar way to Nazi architecture) is a point to think about in its own right. The lecture was structured as a dialogue with Dr. Noam Chomsky who temporarily became a psychoanalyst for Morris. In questioning his own role as an American sculptor, Morris's self-critique bypassed the question of an artist's bios being defined, exposed and marketed, and thrust directly into the artist's unconscious complacency. Unknown to himself, his desire to create has been subsumed by the American imperialist project: 'What makes Jackson Pollock's canvases function as banners for a world empire? First, their implicit defeat of European painting; second, their focus on energy to sustain the agonistic strain; third, their pragmatism in harnessing process. The pessimistic attitude, always judged anti-American, is generally disqualified.' Filled with ambivalence, towards the end of his 'dialogue' with 'Dr. C', Morris attempted to invert his own assertions and defend himself unsuccessfully. He could not find any other justification apart from the unconscious status of American art's 'self-importance': 'Meaning leaks from the beginning, at the unconscious level of desire. A desire to lean a metaphorical sign for American power. Allegories of the sublime are always multiply political. Our version of the sublime does not valorise revolution, but that peculiarly American status quo of domination and blindness. A refusal of memory and the Other is to be expected from such an unconscious enterprise that asserts the present as the only temporal dimension.'

The exception amongst all this self-referential gloom was the lecture by the Atlas Group, whose actual existence might merely be the invention of ‘spokesman’ Walid Raad, along with the enormous historical archive it has puportedly collected and meticulously classified. If this is the case, Raad's eloquent, authoritative, professional, and elegantly designed PowerPoint presentation is in itself a remark on the questionable, but always operative, plausibility of lectures delivered in an institutional context on topics that the audience has had no direct experience of. (Here, everyday life and prisoner experiences in the ’70s-‘80s Lebanon). The arbitrary decision to only publicise a tiny part of the archive, and what it contains, makes one suspect its fictitiousness. The records the Atlas Group decided to show reveal an obsession with the trivial, symptomatic of the growing banality of car bombings, political coalitions between religious fundamentalists and leftists, exhaustive surveillance systems and the everyday lives of political prisoners.

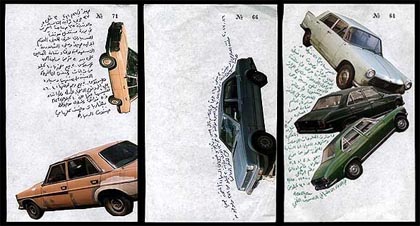

> The Atlas Group, The Fadl Fakhouri File, pages from Notebook Vol. 38

> The Atlas Group, The Fadl Fakhouri File, pages from Notebook Vol. 38

Such banality makes the Lebanese academic Fadl Fakhouri, whose notebooks Raad demonstrated, focus his attention on collecting trivia such as magazine photos of the original model of exploded cars, newspaper pictures of engines that had travelled miles after the explosions, and of politicians who posed near the car pieces after each explosion to manifest their concern. In a tragicomic way, he systematically collects such spectacular images of havoc and related information with scientific impassivity. Another possibly fictional data gatherer, surveillance camera Operator #17, records Beirut sunsets each afternoon instead of secret agents' congregations, while there are records of American political prisoners coauthoring books about their prison experiences with their wives, puportedly to establish their masculinity after homosexual encounters in captivity. These archives could have been real – if it were common practice for historians to collect records which express everyday desires that transgress the immediacies of a tumultuous political context.

Ways of interpreting art and its overdetermined social role was largely the lesson 'artists with the tools of academia' were offering here – despite institutional assertions that today art does not aim for interpretation. Clearly, artists were taking the role of critics, and at a time when the narratives of individual creativity, competitive innovation, and the artistic personality are being reinvented through art marketing and post-fordist labour practices, while American imperialism is becoming increasingly overt, such a critique is necessary. When it reaches dead-ends of self-incrimination, however, critique can lose sight of the political landscape it sets out to address. It is perhaps at this point that jumping out of art history's self-referential rut and surveying banal everyday life could be much more revealing.

Short History of Performance: Part II, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 18-23/11/03 http://www.whitechapel.org/content382.html

The Atlas Group Archives http://www.theatlasgroup.org/

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com