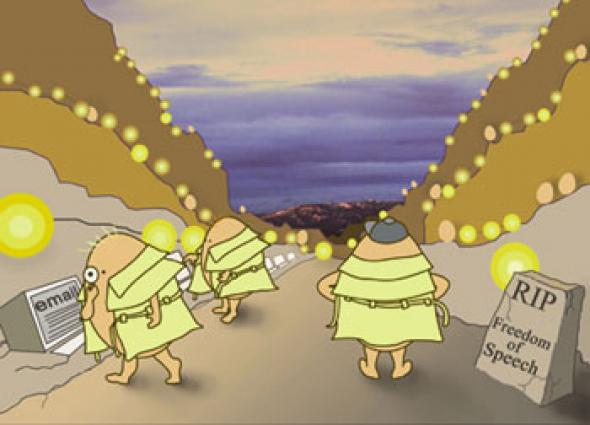

RIP Human Rights

Is the government’s recent Internet bill just one more in a long line of blasé human rights abuses operating under the guise of harmless technological regulation? JJ King reports.

When the Electronic Commerce Bill surfaced late last year, with all its talk of enabling e-commerce by establishing new standards for doing business online, there was an immediate outcry over its third section. This aimed to amend the 1984 Telecommunications Act in order to take into account new developments in digital communications. As a result of the outcry over the civil rights implications of those amendments, the offending elements of the Bill have been removed and dumped into the the Regulation of Investigatory Powers (RIP) Bill, which went through parliament this month on its third reading.

The RIP Bill is intended to "make provision for and about the interception of communications, the acquisition and disclosure of data relating to communications, the carrying out of surveillance, the use of covert human intelligence sources and the acquisition of the means by which electronic data protected by encryption or passwords may be decrypted or accessed." In short, it’s intended to allow the government to monitor emails, Internet use and other forms of digital communication in the name of (according to Section 20) national security, preventing or detecting crime, preventing disorder, public safety and the protection of public health. That in itself may sound reasonable, but what emerged during the third reading was that a wide range of bodies, including the Eggs Inspectorate, will have access to your email and websurfing habits under the provisions of the Bill. No joke, these are the guys who check the nation’s eggs — even the Labour government was too embarrassed to mention them in the text of the Bill.

Worse still, the legislation that will now go forward to the Lords clearly contravenes basic human rights. Were the Eggs Inspectorate or the MI5, for instance, to demand that you hand over your encryption key or passwords, you could be gaoled for two years for failing to do so. Now, it is bad enough that this criminalises the widespread, innocent use of encryption by making the act of losing keys or forgetting passwords a criminal offence. But it also contravenes Articles 6(1) and 6(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights, which concern the right to a fair hearing and the presumption of innocence. In asking you to prove that you were not in possession of a key at the time in question, the Bill clearly reverses the burden of proof. Liberty, amongst other human rights groups, have called the Bill ‘repugnant’.

But the problems do not end here. As a key part of the Bill, the Home Secretary has reserved the right to demand the installation of specific devices to monitor Internet Service Provider traffic — with little deliberation or consultation, no guarantee that the nature of this monitoring will ever be publicised, and no corresponding checks or balances on law enforcement. Employees of ISPs will be compelled to keep any surveillance they conduct on their customers secret in perpetuity — a rather dangerous extension of their obligations. Since we in the UK have only one commissioner — the somewhat superannuated Lord Nolan — in charge of scrutinising the interception of communications in the UK, and since he is already having to deal with the huge increase in phone-tapping warrants issued under the Labour government, the opportunities for abuse would seem legion. Nolan’s claim to have reviewed all 1,646 taps approved by Jack Straw in 1998 personally (aided by his secretariat of, erm, one) beggars belief. So does the notion, espoused by the outgoing chairman of the parliamentary intelligence committee, Tom King, that Nolan’s scrutiny of email taps will ensure that people "can at least know that they’re not being improperly intercepted."

MPs voicing these civil objections in parliament have been disgracefully few and far between. The Opposition preferred to focus on its serious consequences for the UK’s Internet industry, which is, indeed, another legitimate concern. By putting a new set of burdens on even the smallest ISP, the government will effectively suffocate the ISP industry. This risks a series of knock-on effects in which businesses who use electronic means to secure client data may relocate operations to other countries. Indeed, the FTSE-listed cryptography vendor Baltimore Technologies has already set up in Ireland partly as a result of assurances from the Irish government that key recovery is off the agenda.

Germany and France are also both leaning towards banning key recovery, on concerns that demanding cryptographic access creates an unacceptable level of civilian and corporate insecurity. Charles Clarke, the UK Home Office minister responsible for the RIP Bill, has said recently that keys, rather than plain text, would be demanded only in ‘exceptional circumstances’. This all begs the question of why the legislation is necessary at all, since there is a genuine risk that the RIP Bill may be devaluing the UK as a place to do business.

This Bill, which never claimed the attention of more than a dozen MPs during its third reading, effects a huge increase in surveillance powers in the UK. It does so by virtue of the fact that the surveillance of digital communications is regarded as far less serious, as the Home Office minister admitted, than the tapping of phones or the breaking down of doors. Long term, as more and more of our lives are conducted over the network, that perception will not hold, and the Draconian powers of the RIP Bill will be seen in their true light: a further outrageous infringement on our civil liberties in this, the most surveilled country in the world. It is now down to the Lords, and to the forthcoming Convention on Human Rights, to amend the Bill in a way which will admit basic civil rights. With any luck, those amendments will also give an eleventh hour reprieve to e-commerce, and indeed any commerce at all, in the UK.

JJ King <jamie AT metamute.com>

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com