Rewire Yourself

Liverpool's recent Rewire conference looked to advance new and progressive readings of media art and theory. But, asks Lorena Rivero de Beer, who was it speaking to and in whose interest?

I can't start this review without giving you some background about how I arrived at the Rewire conference and the subjective position that it conveys. The latter feels not only important to help you make sense of what I am saying but also an ethical duty, so please, bear with me.

Rewire took place the week following the Free University of Liverpool (FUL) DIY curriculum building workshop. FUL is an initiative set up as a protest against the instrumentalisation of higher education and the rise of its fees to £9,000. The FUL meetings took place in the dungeons of Next to Nowhere, a radical social centre in the centre of Liverpool. Getting out of the dungeons to arrive at the new, shiny, aseptic, £27 million Art and Design Academy building at Liverpool John Moores University to attend a £150 fee conference, was a shock; straight back to the core of neoliberal academia and its blending of high elitism with customer service culture... Still I was excited about the opportunity to attend the conference for free, with the journalist pass, and the privileged access it gave me to a specific form of knowledge within what was announced as a critical and progressive conference.

In our FUL meetings in the damp dungeon, the sophistication, intensity of the interaction and level of discussion was difficult and wonderful. Within our discussions we thought about how to use new technologies ethically, questioning the effects that using them might have, thinking about how they can be useful tools for transnational encounters yet how they can also produce meaningless interactions, how, even though the web is an incredible information resource, issues of accessibility (who can access the net and how people with access to it might process the information depending on their background and skills) are still fundamental problems. So I hoped Rewire would fill me with new conceptual frameworks that we could then apply to our thinking about FUL regarding visibility, media coverage, networks, how to apply or think of new technologies in creative and subversive ways, and most importantly, how to think about accessibility.

Like most big conferences (even if there are much bigger ones out there), the amount of sessions, panels and papers was quite overwhelming. There were four sessions every day, each of them with three different panels, which had between four and five speakers. Besides this, there were also parallel talks, exhibitions and performances as part of the AND festival taking place in the evenings and following weekend. While being at the different panels listening to papers ‘til I couldn't take on anymore, I kept thinking about why a conference about media art – an art form that critically explores both the inhuman sides of the media and its modes of social engagement, as well as the creation of interfaces that open up possibilities for more sophisticated collective encounters – was carried out in such a conventional way. A way in which access to knowledge was very difficult and fully dependent on a restricted academic language; that is, a logocentric means of communication that secures and conveys hierarchical positions. Of course the different levels of experience of the speakers and some of the more creative presentations made a difference, but still the insurmountable volume of information, the cold and detached atmosphere and that specific use of language made it almost impossible to share knowledge in a progressive and meaningful way.

As an effect of this language it was very difficult to establish the conference's real nature, where the power lay and who was having an effect on the wider discourse. That information would be more or less accessible to the attendees depending on their background and their access to specific networks; so within the apparent choice, transparency and richness of multiple voices, complex forms of power distribution were operating. As a relative outsider to the field with not much to gain from it in terms of networking, I felt in a privileged position to observe its mechanisms. So I experienced the complexity and I felt lost within the seemingly diverse content of the papers that navigated through a hierarchical discourse marked mainly by institutional powers and presenters' publishing records.

To talk about content and the nature of the different papers in that context I decided to use one of the strategies we used at the Free University of Liverpool to classify the books in the library; a classification aimed at revealing the power hidden in disciplinary divisions and also to reflect upon the subjective positions through which they are made. The FUL library was catalogued as follows: Most important books; Very Important books; Not so important books; Who cares books. Everybody participating in FUL could change the order as they wished and would have to negotiate with others if there was a disagreement. To catalogue/review Rewire I changed books for papers and classified the ones I attended accordingly. Through this approach I intend to generate a space to reflect on the relationship between the discursive normativities operating at the conference and our (hopefully) slightly unruly subjectivities.

Unfortunately no paper fell into the category of Most Important Papers. This category was created for books we loved so much they deserved a new category. I think some of the papers in a different space might have provoked real love, but the context made it really difficult.

Under Very Important Papers I included some interesting papers that looked at notions of functionality and failure, desire and technology, opening up a place to consider how media art can support our understanding of notions of subjectivity, new modes of interrelations, and so on. Within them some were backed by progressive philosophies with special emphasis on thinkers such as Gilles Delueze, Jacques Derrida and Rosi Braidotti.

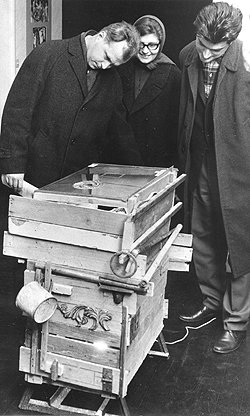

There were particular presentations that really put their finger on important issues. Through a clear and concise presentation Maria X asked questions about her project media@terra, interrogating what its failures might have been. While questioning the scale of her project she asked: what does it mean for a grassroots initiative to become co-opted by governmental and corporate structures? On the same panel Morten Søndergaard introduced POEX 65 – a transdisciplinary exhibition mounted in Copenhagen in 1965 by a group of 80 international artists, curated by Knud Hvidberg – that aimed at breaking the boundaries of art genres and the autonomy of the ‘work of art' through the active use of technological and mediated platforms. Søndergaard asked important questions about why such experiments faded away and failed to become part of the history of media art. That panel generated important connections between historical failure and meaningful, politically progressive initiatives.

Image: Robert Corydon's Poetry Machine contribution to the exhibition POEX 65, held at the Free Exhibition Building, Copenhagen, December 1965

The presentation by Armin Medosch was excellent. Medosch introduced the early phase of the movement New Tendencies (NT) before it was absorbed by the market. He contextualised his aims politically and defined his project as a research into politically progressive media art.

Certain papers were particularly important because they managed to reveal through their argumentation the position of power taken by other papers on the same panel. I particularly enjoyed the views of Janis Jefferies, her discussion about breakdown and the aesthetics of disappointment which gave a voice to our human fragility. On that same panel Magdalena Tyzlik-Carver introduced important and problematic questions about curatorial systems that bring contingency to the forefront and questioned the immaterial labour demanded from audiences in participatory art.

Alessandro Ludovico and Paolo Cirio described how their mass media intervention – in which they stole a million public profiles from Facebook, filtered them through a face-recognition software, and then posted a selection of 250,000 profiles onto a dating website called Lovely-Faces.com – gained huge media coverage, a massive public response and a ‘Cease and Desist' letter from Facebook's lawyers. They reflected on how the project exposed the vulnerability of our social identity. This was important as they brought the notion of cultural intervention to the fore and reflected on some strategies to destabilise media-normative social powers.

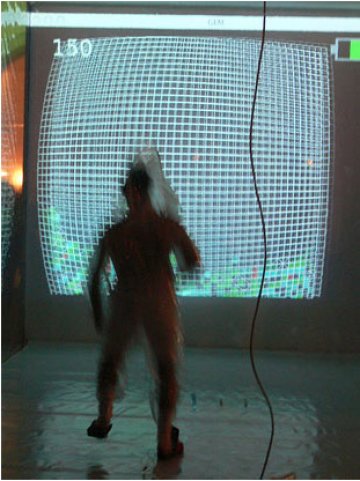

The paper by Dot Tuer tracing back alternative histories of media art to the Rosario group in Argentina, and linking them to the recent work Thirty Days of Running in Place by artist Ahmed Basiony, brought in a much needed non-Western and politicised perspective. I wish though she had reflected on the complexity of the position from which she was speaking as a western academic.

Many papers I saw were interesting, if mainly descriptive. There were some Not So Important ones, and in the worst cases I would say also ideologically dangerous, since there was a near total absence of self-reflection and self-positioning within wider social issues. They somehow managed to avoid the tensions and complexities of their different positionalities. A clear example of this was Jonathan Lessard's paper looking at the way game genre designs are adapted to technology. It was fun, interesting and well articulated; it would be a brilliant introductory talk for anyone selling games.

There were some particularly well articulated papers that could have opened a space for discussion, but fell short of approaching issues of more central concern. Saskia Korsten's paper for instance, which reflected on our relationship to digital images that hide their relationship to the analogue model, would have been a great if it had ventured a broader consideration of accessibility.

Some papers felt potentially interesting and transformative but were somehow too obscure so their point was lost in abstract theories that didn't make enough of an effort to reach others. This was the case with Emile Deveraux who introduced an interesting although intricate idea about porousness in technology.

Image: Thirty Days of Running in Place by Ahmed Basiony

Particularly lacking in the conference, I felt, were discussions about the role of new media in the creation of alternative communities from the perspective of those communities' members, rather than a detached or managerial overview. The exception (from what I saw) was Benjamin Juhani Halsal who discussed his university project in conjunction with Leeds Visual Art Forum. Through a series of conversations they set up a Yahoo! group to serve the visual arts community in Leeds. He discussed how it supported artists promoting their activities within a horizontal space while questioning the alienating effects of this mediated community. Presenting this kind of project is fundamental and empowering, but the paper didn't critically position artists or question what that horizontal space means in wider society.

Within this category I also included some papers that explored current artists projects. They were taken from different perspectives like the presentation by Sander Veenhof in which he questioned the existence of Art 2.0 and how audiences become co-producers of their work, or Heidi Tikka's description of her installation Mother, Child and discussion of the mess and failures which occur in media works.

The position of power taken by certain presenters really pushed me to think Who Cares about what you are saying! Papers such as those presented by Christiane Paul, Margriet Schavemaker or Vince Dziekan, enacted the reproduction of hierarchies in the world of media art by positioning speakers according to the scale of institutional power that backed them. The decision of one of the head figures of the Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), Margriet Schavemaker, to defend media art spectacles over critical content felt particularly contentious. In a world in which we are swamped by media spectacle that ensures we remain a submissive and consumerist society, isn't it fundamental that we make art spaces remain (or become) a tool for critical reflection?

Based on the approximately 40 papers I heard out of the approximately 140 papers that composed the three day conference, it's fair to say that the event opened up interesting areas of research and contributed towards the expansion of notions of media art, new technologies and science. It explored the histories of media art by tracing back its origins to interesting and obscure projects that have faded over time, it made visible the movement back and forth between the digital and the analogue, it made links with ‘Other' (non-western) cultural histories, it introduced current projects, and expanded the power of its discourse by looking at it through the lens of important progressive philosophies. I am not sure, though, if it managed to move beyond reinforcing its own canon, or if it benefitted something other than itself by the effort of securing a position for its proponents in a Western History with no sense of shame as to the colonial and neoliberal implications attached to this.

A discussion around the radical potentiality of new media art and technologies to open up space for real alternatives to exist while also closing them down because of issues of accessibility was not present. In the current historical situation, such discussion is not only central but ethically unavoidable. Judging events from that perspective, many presentations were difficult to take. With a few wonderful exceptions, most speakers talked from positions of extreme privilege, without questioning themselves, and took reductive and patronising approaches to media art audiences.

The final keynote speaker, Andrew Pickering, finished the conference with a talk that advocated humans becoming aware of their instability and a self which is caught up in the flows and transformations of becoming. Funnily enough he ended the talk with a proposal for a new University that can systematically teach how to think in a new mode of being, one in which the modern relationship between the active subject observing the passive subject is problematised so we find a way of connecting to the world, instead of dominating or framing reality. I agreed fully with that final note, and that's why I am engaged in the creation of FUL. FUL is a protest and has as its main aim the uncovering of the mechanisms through which institutional powers allow some people to develop more than others. It also aims to uncover how institutional powers prevent all of us from flowing and becoming, in order to keep social hierarchies working. To be able to even think of the structural shape of the space that will allow becoming to stay at the core of any pedagogy we desperately need to join forces and think how to create places that help us to flow while providing us with the strength to question and resist the rigid channels of institutional purpose. I wonder how that final talk affected the other people listening to it. To what extent they felt it reflected on their own research and how their research is contributing to building a world in which we, all of us, can understand that we are in the constant process of becoming?

And a final note, something I found quite paradoxical and I really liked was a sentence written on the back of a T-shirt of one of the main speakers. It said: 'Fear is not an option'.

Lorena Rivero de Beer <lorenajohanna AT hotmail.com> is an artist and producer based in Liverpool. She is the co-founder of the Free University of Liverpool and Tuebrook Transnational, a company that creates site-specific outdoor performances/interventions collectively with other residents of North Liverpool. She completed a PhD in 2009 at the Department of Sociology of the University of Essex exploring the relationship between cultural politics, representation, aesthetics and subjectivity in relation to the Chicano performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com