The Return Of The Poor Law Mentality

Surveying Channel 4's recent troika of poor-bashing TV series, Alastair Kemp asks if this is the revenge of the disciplinarian society or the spectacle of something new?

'I think we acted in perfectly good faith in [helping] a family that looked like a decent deserving family' says philanthropist Ken in the first episode of new series, How The Other Half Live, by RDF Media group. Is this the spectre of the deserving and undeserving poor rearing its ugly head again?

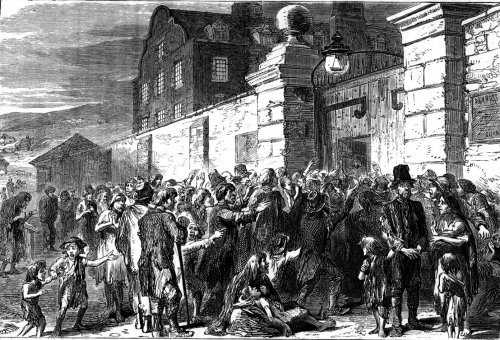

Image: At the gates of a workhouse

RDF Media Group – bought out last year by its executives with the help of John De Mol, the executive behind Big Brother – was also behind another Channel 4 series, Secret Millionaire. The attitudes of the two programmes towards poverty becomes all the more striking when contrasted to the attitudes of the rich during the time of the New Poor Laws in the late 19th and very early 20th century. Whilst Secret Millionaire has the philanthropist mentality of early social researchers into the urban poor such as Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree, How The Other Half Live goes straight to the heart of the beliefs of the Charity Organisation Society, an organisation that tried to limit charitable poor relief to the deserving. Helen Bosanquet, one of its founders, was a major campaigner in this respect, and her organisation would provide morality tests for charities giving out relief to the poor, having no qualms turning away those considered drunkards, idle or generally morally weak. For this reason turning to charity was looked upon with horror by many of the poor during this time due to the moral inspection involved. In the second episode Shaun, the Brighton bus driver, repeatedly mentions the blow to his pride. Meanwhile his wife, having bought a laptop for her dreamed-for business, is brought to confession at the Spanish Villa of her rich benefactors and chided for not spending that money on her children. All agree with satisfaction that she had been selfish. A modern Dickensian epic tailor-made for reality television.

Above all, the premise is that How The Other Half Live is bringing the Sponsor A Child style of charity developed by Save The Children and others to the UK’s own poor. That Save The Children’s American twin in child sponsorship, Foster Parents Plan (now Plan International), was one of the few charities able to work in El Salvador when all other aid agencies had fled – their projects destroyed and many of their recipients murdered – has, as opposed to its own claims of success, also been levelled as evidence for its very inoffensiveness. In a controversial article in the New Internationalist written back in 1982, Peter Stalker argued that despite the immediate emotive attractiveness and ability to raise large amounts of money, these schemes weren’t such a great way to spend it, there were other more effective ways, but these other ways were more politically sensitive.1 This inability to upset the dominant hegemony suggests that this charitable method’s own ability to provide long-term lasting change for the world’s poor is limited. Furthermore there are questions concerning what such personal charity can bring to the wider community, and the way the entrenchment of its focus on one area creates problems for the scope of its effectiveness. When brought to bear within the benefactor's own society, for the viewing pleasure of both sides of the effective scope of the program, not to say those caught between, the motives behind both charity itself and charity as entertainment become that much more sinister.

While still bringing the personal to charity, Secret Millionaire judges the charities themselves, not the poor, and as such has the Whiggish attitude of the New Liberals of the early 1900s settlement movement, in which young university graduates would spend some time living in poor areas before coming to the conclusion that laissez-faire may not be the cure-all they’d dreamed of. Still, the characters deemed worthy of the philanthropists’ cheque are often mirrors of the philanthropists’ beliefs about themselves if only they would jack it all in, stop trying to make vast amounts of money and actually physically put something back rather than just write the cheque – perhaps truly signifying the normative power of writing one. The charity workers are all caring, most definitely hard working, energetic and driven. At least any judgement of the deserving or undeserving poor is left behind as the benefaction is based on the results of these community actors. That community groups can apply to the production company for consideration just moves it one step closer to community funding as entertainment, removed from the whims of central and local government and returned to the hands of the individual. Another Whiggish dream.

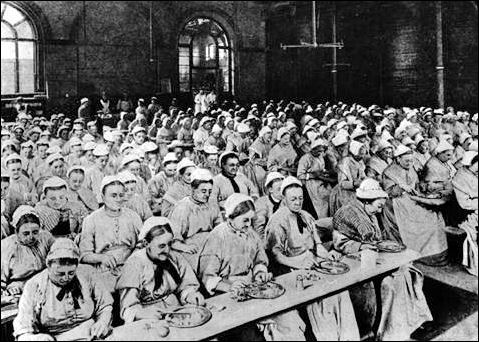

Image: Inside a workhouse

The benefit of Secret Millionaire is that the entertained viewer can see the poverty and degradation as well as the positive attempts to alleviate it. The charities get a chance to speak for themselves. It was the publicised research of Booth, Rowntree and others as well as the cruelty of the Workhouses and their inadequacy during the Great Depression of 1873-96 that led to pressure on the Liberals to reform the Poor Laws. That these reforms – The School Meals Act (1906), Children’s Act (1908), Old Age Pensions Act (1908) and National Insurance Act 1911) – were far from universal, while the Charity Organisation Society still kept the morally weak needy barred from receiving them, meant that the idea of the undeserving poor had not yet gone away.

Worryingly, complicit with the belief in the deserving and undeserving poor was the belief that those who took from the State were somehow less than full citizens. Although the Liberal Poor Law Reforms predate universal suffrage (yet the Poor Law was not formally abolished until 1948, some statutes even remaining until 1967), those poor who had to turn to the workhouse not only had their freedom curtailed but also any voting rights they may have had. So what tendency does How The Other Half Live portray? We as viewers, along with the benefactors, are invited to assess the moral worth of these poverty stricken supplicants, sneering at their selfishness, so that they already become less than human. Where next for their rights?

If Secret Millionaire sheds light on the development of the new discourse on community funding, How The Other Half Live seems to tend towards the development of a new populist attitude towards the very poor. Very prescient at this financial time. Just starting up on Channel 4 on Thursdays is a new series, Benefit Busters, looking at the new breed of results based, privatised or charity based worker employed to get the previously hard to reach unemployed; lone mothers, disabled, sick back to work. With the government looking at making the universal welfare state profit-orientated, the publicity for this program seems to be focussing on the clash between disciplinarian management, their beliefs in a lazy, unwilling workforce and the upset of those under this hammer. That this program is made by Studio Lambert, the company set up by ex-RDF executive Stephen Lambert after he left RDF due to the BBC A Year With The Queen controversy and the man originally behind Secret Millionaire, will come as no surprise.

Image: Attack on a workhouse

Is there an agenda here from Channel 4, or at least RDF and those associated with it, perhaps a personal one for Lambert? Perhaps not: these programs hark back to the disciplinarian society of the Victorians, and just as the scientists heralded by Dawkins, Dennett and Pinker are fighting the Christian Right for hegemonic control of access to absolute truth, so as we move to a new society, perhaps from a disciplinarian society to a society of control, the old geneaological characteristics put up a last fight to make sure the transformation occurs on their terms. Hegemony is largely accidental. In this sense, there’s no conspiracy, no conscious manipulative masterplan, there’s no need – propaganda has become public relations. All those involved in these three series most likely believe wholeheartedly in their values, both those filmed and those doing the filming. But with the necessarily greater influence on all types of discourse that the accumulation of capital brings to bear, the better-off have therefore always had a greater influence on the morality of our collective lifeworlds. Now, finally, we’re having it spelt out for us. As bus driver Shaun says at the end of the second show, having had a glimpse of 'how the other half live':

It’s proof that it doesn’t matter what your background or what your upbringing, if you work hard you can achieve anything.

Sorry, Shaun? I thought you did work hard.

Alastair Kemp <alastair.kemp AT yahoo.co.uk> is a writer specialising in art, care in the community and mental health, music and social theory, he is studying a DPhil in Social and Political Thought at the University of Sussex and he is the host of the Contemporary Arts Show on Radio Reverb 97.2fm (www.radioreverb.com) Brighton's community radio station

Info

The first episode of Benefit Busters will be screened Thursday 20 August, 9pm, on Channel 4

Footnote

1Peter Stalker, ‘Please Do Not Sponsor This Child’, in Brazier C (ed.), Raging Against The Machine, Oxford: New Internationalist Publication, 2003.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com