The Regeneration Game

The notion of ‘regeneration’ is often used to underwrite new urban development schemes. In London, agencies such as Cityside Regeneration claim to be generating massive new opportunities for the local community. But increasingly, campaigners are asking who regeneration really benefits. This is the question at centre of the Spitalfields Market Under Threat campaign in London. Jemima Broadbridge, SMUT’s media spokesperson, explains why this is more than a local campaign.

Spitalfields Market, situated in the shrinking hinterland between London’s City district and its fashionable East-end, is both a food market, a community centre and a base for a number of thriving businesses. By night the space is used by rollerbladers: by day, city workers and bike couriers alike get lunch from one of its many stalls. On Sundays, Spitalfields plays host to one of the most popular organic markets in London.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given its prime location, property developers are desperate to submit the market to their vision of ‘urban regeneration’, in the shape of more than half a million square feet of offices erected over most of the present market site. Critics point out that the firm of international lawyers slated to occupy the offices will have little call for local workers. In fact, with local employment rates in the market standing at 75% and 300 stalls presently operating in the Sunday market, it seems likely that many jobs will be lost to the Spitalfields community as a result of the development.

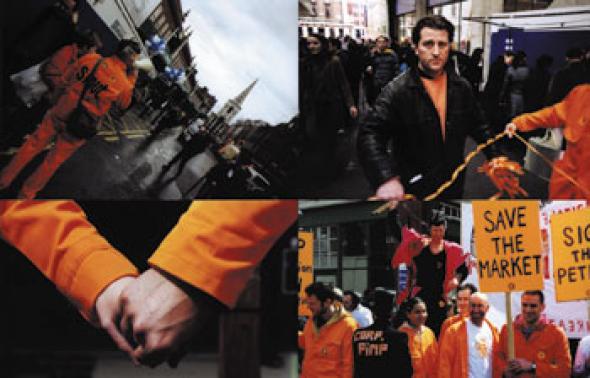

This, surely, is not regeneration but degeneration. The Spitalfields Market Under Threat (SMUT) campaign, a coalition of mosque, church, community and small business associations, is currently lobbying the Greater London Authority and the Mayor to veto the latest plans for the market. Although we do not anticipate a positive decision (the Corporation and its developer are due to pay £18m to the London Borough of Tower Hamlets as a condition for planning permission, a sum the cash-strapped council can ill afford to refuse), it is hoped that through continued lobbying of MPs and English Heritage, we can raise awareness of the problematic notion of ‘regeneration’.

There is still a serious gap between policy and practice when it comes to honouring the participatory, ‘bottom up’ ideals the UK government claims as a central part of its vision for urban planning. In its White Paper on Urban Regeneration, the government promised to “put people first” in development plans, engaging us in “partnerships for change with strong local leadership and sustainable growth.” It is difficult to see how plans for Spitalfields tally with this rhetoric. Nor is Spitalfields an isolated case: the battle to preserve public space from often predatory private interests is currently being played out over listed buildings all over London, from Kings Cross threatened by the new Crossrail link, to Borough Market, faced with extinction in the face of Railtrack and the Government.

We use the term ‘brightfield’ – describing a site that provides colour, character and relief from other forms of city life and brings people together in both economic, social and recreational ways – to describe places like these and Spitalfields. It is the very centrality of such sites in city life that puts them under such pressure from real estate developers. Yet brightfields are far more valuable as centres for the urban communities that live around them than they are as bulldozed building sites. Through the SMUT campaign we hope to bring this message not only to the locals(who already understand it all too well) but to the broader public and, most importantly, the government.

Jemima Broadbridge <jemima AT broadbridge.fsnet.co.uk>

For more information on the SMUT campaign: http://www.smut.org.uk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com