Paper Dolls

How does open source software relate to paper dolls, dress making, libraries and dinner parties? Lina Dzuverovic Russell talks to the De Geuzen art collective and discovers how the geek ethos overlaps with the practice of everyday life

‘When people walked into the Royal College they simply wiped their feet across democracy and entered the exhibition’, explains Renee Turner, one third of the Amsterdam-based art collective De Geuzen. Turner is referring to a custom made doormat with the word ‘Democracy’ printed on it, De Geuzen’s contribution to the eponymous exhibition at London’s Royal College of Art in 2000.

The piece was typical of the symbolic collisions that De Geuzen engineer in all their work. Dedicated to carrying out playful, user-friendly exercises within familiar contexts such as dinner parties, guided city walks and symposia, De Guezen play a wide repertoire of roles – pseudo-librarians, dinner hostesses, seamstresses. The collective balance between hosting events in their Amsterdam studio and putting on projects in public spaces. Recently, invitations to participate in international events have taken them on the road and the trio have had to learn to be flexible, working from hotel rooms, corners of cafes and, at one point, even from the furniture section of a department store.

The De Geuzen girls - Renee Turner, Femke Snelting and Riek Sijbring - met during their studies at the Jan Van Eyck Academy in Maastricht and went on to collaborate on multidisciplinary projects, combining their skills in design, fine art and cultural theory. De Geuzen was born in 1996 as the Foundation for Multivisual Research.

As they morph from one role into the next, the one constant in the work is a commitment to empowering the ‘users’ of their projects. Just as the open source movement enables users to freely modify the source code of computer software, De Geuzen make tools available to allow communities to actively participate in their projects and eventually, at least in theory, turn them into their own. In the case of De Geuzen, we are not talking about source code but its equivalents in everyday life: dress patterns, book collections, attachable slogans. While addressing the complexities of distributed authorship and negotiating the relationship between producer and consumer, De Geuzen make it clear that they are far from sanguine about the religious zeal which surrounds the open source movement. In their recent projects, the language of ‘Copyleft’ and the open source movement is mixed with symbols of military power – an ironic comment on the evangelism often displayed by media workers and activists in discussions about skills and resource sharing.

Much like the offline components of their practice, the geuzen.org website is a whimsical take on ciphers of femininity, the role of the artist and notions of public and private, its tone poised between theoretical analysis and frivolous word and symbol play. With sections such as De Geuzen Uniforms and Instructional Manuals For Popular Use, the visitor is lured into a world filled with musings on the issues of female activities, labour and domestic space. Describing themselves as ‘domestic users of the net’, De Geuzen are interested in exploring the analogous relationship between open source production and everyday, domestic activities: ‘We are by no means technically minded,’ says Turner, ‘but we do relate to the open source approach. It’s really the modern word for sharing and building on various sets of knowledge or experience. Think of the housewife who posts her favourite recipe only to have it prepared and adapted by someone else, or home gardeners who offer online fertilising tips. Like these people, we are domestic users of the net as opposed to those who understand the mechanics of it. We tend to bring our analogue experiences to an online environment while taking advantage of what the virtual realm has to offer.’

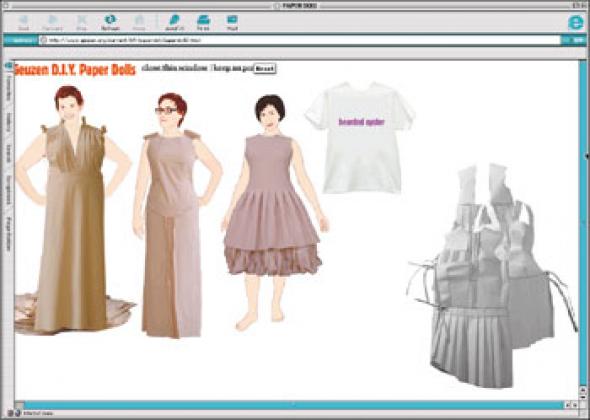

In the DIY Paper Dolls section of the website you get to dress models of Riek, Femke and Renee in the various different uniforms by dragging the outfits over to their smiling forms. But playing with De Geuzen dolls is an absurd rendition of the dressing up game since nothing seems to fit. In contrast to the Barbie-like proportions of the paper-dolls we know from childhood, Renee, Femke and Riek use their own proportions, inviting us to go away and make our own uniforms for our own bodies. De Geuzen’s device of contaminating the generic with the particular calls to mind the feedback loop between collective production and individual customisation exploited by open source programmers.

The most recent addition to the website is a series of De Geuzen uniforms. Based around of a set of evolving vows which refer to their collectively negotiated work ethic, each uniform embodies one aspect of their practice. The stern Utility and Service uniform is a take on the artist as hostess. In a twisted combination of images we see Renee looking like an eager-to-please air hostess next to an image of three uniforms hanging on a gallery wall like deflated dolls. Taking yet another ironic swirl, they enter the world of fashion magazines, meticulously describing the uniforms in terms of the quality of the wool and the uses they can be put to. We are assured they will be suitable for both ‘formal and informal occasions’. Meanwhile, the luxurious Frivolity and Folly uniforms are printed with Geuzennaams, a set of derogatory terms appropriated and reclaimed as a positive label of empowerment (‘bearded oyster’, ‘bra-burner’, ‘’er indoors’). The DIY uniform is printed on newsprint and comes complete with an elaborate set of instructions while the white t-shirts in the Simplicity and Ease category come with all the tools you need to print your own Geuzennaam.

Symbols of domesticity and everyday activities recur in De Geuzen’s studio practice. Their Mediated Image Series ,1999, incorporated a dinner themed around the ideas contained in French philosopher Michel de Certeau’s book The Practice Of Everyday Life (1974). Wearing aprons decorated with quotes by De Certeau on diversionary tactics in the workplace – his concept of ‘la perruque’ – invited speakers amongst the audience recited De Certeau texts in place of after-dinner speeches. ‘The experience was like a dinner serenade or an evening of storytelling,’ they recall. ‘Because we were the waitresses, we had a very intimate relation to our audience. It seemed important to engage with [De Certeau’s] work in an accessible manner. A meal seemed to be the perfect medium. In spite of the tremendous amount of dishes we had to wash, the experience as a whole really worked.’

Away from the studio, De Geuzen regularly set up temporary research spaces and archives in art centres. In the Temporary Archive at Manifesta in Ljubljana, 2000, and the Walk-in Reader at Amsterdam’s De Appel, 1999, De Geuzen created personal libraries, catalogued according to an elaborate set of cross-references, by volunteering their own book collections. Soon, regular visitors started bringing their own material to add to the archives. ‘There was something almost viral about the way these collections grew, and the space changed as a result,’ says Turner. The archives are often placed in traditional artworld contexts which are conceptually far removed from the open source ethos of resource-sharing. In their capacity as open, collectively developed resources, these projects function as an implicit critique and exploration of the traditional territorialism of art institutions, as they displace the roles of curators, producers and educators.

In 2001, Kunstlerhaus Bremen became the base for a collection of DIY projects through which De Geuzen transformed the space into a working laboratory using the Instructional Manuals For Popular Use. Taking over the gallery to install a kind of open source social space comprising of manuals, dressmaking patterns and online references, De Geuzen wanted to create an atmosphere that didn’t feel too precious but was comfortable to work in. ‘We set up working stations with simple tables and all the necessary materials were available. There was a computer, a sewing machine, scissors, and iron, etc. People were surprisingly comfortable with getting down to business. It took only one person to start making an iron-on transfer of their favourite Geuzennaam and then everyone else soon followed. In fact, people started combining words and placing them on their own clothing. Those things you can never completely script because it’s about the audience making the work on their own,’ explains Turner.

‘It is only through interaction, and for that matter occupation, that many of our projects are completed,’ Turner concludes. ‘We really don’t have a singular strategy,’ she adds, ‘tactics change depending on the context or specifics of a particular project.’ In the end, it seems, de Geuzen’s approach can be boiled down to one simple truth: ‘Maybe the long and short of multivisual research could be summarised as “there is more than one way to skin a cat.”’

Lina Dzuverovic Russell <lina AT metamute.com> is an artist, curator and member of the No Alternative Girls collective. She is also web editor for Mute

The full interview with De Geuzen is published on Metamute []

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com