Obama is Preaching Transcendence

When rivalry still openly reigned between the Obama and Clinton camps of the Democratic Party, Ulrich Gutmair spoke to Sci-Fi writer and pioneer of cyberpunk, William Gibson, about American politics, the online age and Voodoo

UG: You invented the term cyberspace when only a few people were online, on an early version of the Internet. What is the most fascinating thing for you on the net today?

WG: I think Youtube. Youtube is this kind of vast, perhaps largely unexplored library of material one can never get to the bottom of. It's amazing and bottomless, the stuff that is on there. Its size increases exponentially every day. Every once in a while a friend of mine with some special interest will discover Youtube and I will be deluged with links to videos of things I never could have imagined existed. If you look up the 1939 World's Fair, for example. The amount of black and white footage of the fair - who would have known? Anything like that finds its way onto Youtube.

UG: In your novel Pattern Recognition, you reflected on how important moving images have become on the net. In the book, we witness the mysterious appearance of films on the net, and everybody is asking themselves what they're actually watching. What is so interesting about this idea?

.preview.jpg)

WG: It was only last year that my fascination with Youtube got into full swing. One day I suddenly realised that Pattern Recognition is a pre-Youtube novel, and it would not have made any sense in the real world. If I had written that book after Youtube had become what it had become, people wouldn't be watching that stuff on forums, it would all be on Youtube. When I realised that, it was like almost being hit by a car. That could come to a bad end, and Pattern Recognition could have come to a bad end, if Youtube had launched earlier. Youtube is like Jorge Luis Borges' infinite library. I think it's on its way there.

The limitation to what you can find on Youtube is basically your own imagination. When I think of something, if I don't automatically think of searching for it on Youtube, I will never see it. When something comes to mind, I try to train myself to google it and then look on Youtube, often with the most amazing results. I think, in the end, if we just kind of run this technology out to its logical conclusion, we will end up with something like a single retina that covers the entire inner surface of a sphere, looking at itself, being quite self-sufficient, and made completely of Youtube videos.

UG: Why did you choose to situate your last two novels in the present day? Some would argue that Spook Country and Pattern Recognition are not traditional Science Fiction novels.

WG: Well, in my heart of hearts I never thought that my previous novels were traditional Science Fiction novels either. When I began to write Science Fiction, I had the self-awareness of an English literature undergraduate. For me, Science Fiction is always about the day in which it is written. If you look at Science Fiction historically, that's the only way to get a handle on it. 1984 is always about 1948. When I wrote Neuromancer, I was conscious of writing about Reaganomics. I was writing about the outcome of that kind of political philosophy. One of those outcomes was that in Neuromancer, the United States is like Mexico City. But there didn't seem to be much of that sort of thought going on among the Science Fiction audience the book initially reached.

So for me, these two most recent books are continuations of what I was actually doing before. It has just become more overt. I have the advantage now of not having to imagine the 21st century because we're actually living in it. We are living in a 21st century that no Science Fiction publisher would have allowed me to depict in 1985. If I had gone in and said: ‘I have got a great idea for a Science Fiction novel, it's a world where human technology has upset the global climate, and it's getting warmer and people are starting to feel that, and the polar bears are dying', they'd say: ‘Wow, that's cool', and I'd say: ‘And there is this sexually transmitted auto-immune disease.' They'd say: ‘Well, okay.' Then I'd say: ‘And terrorists from the Middle East have hijacked airliners and flown them into the tallest building in Manhattan, and then America invades the wrong country!' Not only would they not give me a contract, but they would probably call security. So, for someone writing - whatever it is that I'm writing these days - the world just provides. In terms of material, it's just a constant embarrassment of riches.

UG: Milgrim, one of the three protagonists in the novel, is comforted by a book in his pocket, which deals with medieval millenarian movements, wandering priests who gathered the dispossessed around them and proclaimed that the end of the world was near. That sounds like the classic work of Norman Cohn.

WG: I went to New York to stay with a friend for a few days and refresh my local geography for the book. My friend is a great reader and always has a huge stack of books which he insists I read. I usually don't read them all. He said: ‘Have you read Norman Cohn's The Pursuit of the Millennium?' And I said: ‘No,' and he said: ‘You have to read it. Here, take this. I've got an extra copy.' It is literally the same copy that Milgrim carries around. It's falling apart. So I took it rather reluctantly and started reading it for the first time back in my hotel in New York, and somehow it immediately went into Milgrim's pocket, and became a huge part of the character. It's just a lovely way to understand our present moment. There is so much of that sort of millennial thinking around lately. I found it hugely comforting, and it comforted Milgrim as well. I am not sure that people like to know that authors operate that way, though.

UG: Accidents were very important for a lot of people in modern art.

WG: The longer I write, the more I become convinced that somehow the hardest job for me is to get out of my own way. If I can somehow absent myself while the work is being done, the work will actually be better and find a wider audience. The things I write when I am too involved don't age well.

UG: Now, you describe the way you function as an author as similar to the way some of your characters function - especially the ones who are into Voodoo or Santeria.

WG: Yeah.

UG: They are like mediums, they are not active agents, but let things flow through themselves.

WG: It's mediumistic. I am channeling, but I am channeling myself, that's the difference. I take it for granted that it's me. When people write creatively, they channel aspects of themselves that they don't consciously have access to, which is very nerve wracking. It's taken me a long time to feel secure enough to say that publicly, knowing that my publisher might read it. Because I don't think it's what publishers necessarily want to hear either. They want to hear that you know what you're doing.

UG: The Orishas, the gods of Santeria, reappear in Spook Country, and have already populated cyberspace in your first trilogy. What is so fascinating about this Afro-American religion for you?

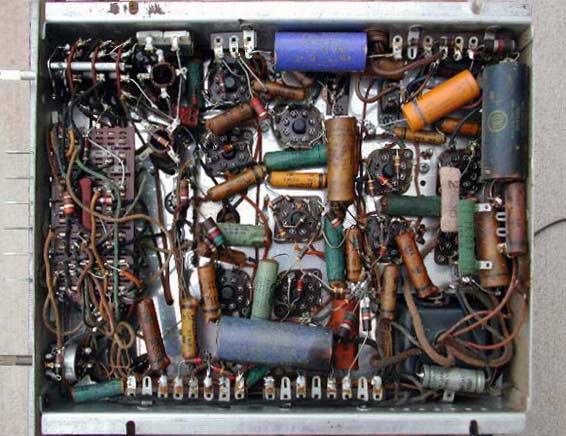

WG: I don't know. I do know that I first discovered it when I was about twelve years old. I had bought a book called Voodoo in New Orleans by Robert Tallant which was a good, serious book; what today we would call a trade paperback. So it was like a cut-up from my usual reading material and in it there were a number of illustrations of the Veves, the ritual signs that are drawn by practitioners of that religion. While I was reading that, I was also building electrical kits that came with instructions. I built a transistor radio and some sort of electrical meter. And when I was reading Tallant's book on Voodoo, the thing that kept striking me was how much the Veves looked like circuit diagrams and they really do quite a lot. And I wondered what sort of device you would get if you used a Veve as your circuit diagram. Many, many years later, when I was writing Count Zero, my second novel, I was very stuck and having a sort of sophomore slump and the narrative wasn't going anywhere. One day I remembered the Veves and the circuit diagrams and that was all it took to jump across to a world inhabited by the pantheon of Haitian Voodoo. However, it is never clear, nor was it ever intended to be in Count Zero, whether they are literally there, or whether they are a simply an incredibly elegant, traditional cultural form in which something very un-supernatural finds it very convenient to manifest itself.

UG: Tito is very into fashion. For example, he loves stuff produced by the fashionable Parisian brand APC. In fashion, are certain shopping decisions related to a kind of magical or religious behaviour?

WG: Brands are stories, and we've always defined ourselves in terms of the stories we believe in. I don't think that's by any means a bad thing. The bad elements are all related to branding abuse, that is, situations in which the actual product - the units you are hoping the branding will move - turn out to have nothing to do with the story you were sold. You buy the story and you get the actual unit home and it's not the vision they sold you at the store. That's bad, that's bad branding.

UG: If one takes a close look at the primaries in the States, one might say that Hillary Clinton stands for the good use of institutions, whereas one of Barack Obama's energising tools seems to be charismatic reference to heavenly help. He is promising a ‘light' that will shine, if Americans re-unite. What do you think about this?

WG: It's a transcendent rhetoric. He is to some extent preaching transcendence: ‘Yes, we can.' When it comes to Hillary, the pro-Obama faction uses: ‘No, you can't,' as their version of her message.

UG: Some people ridicule Obama for presenting himself as a kind of Messiah. There is even a blog dedicated to the phenomenon. If Bush is the real believer, then Obama sounds more like a pop version of religion, very superficial.

WG: I think it's an American modality, and it does not necessarily mean that he would be a worse president than George Bush. Transcendence is part of the American cultural experience and I wouldn't expect it to go away. It hasn't been popular for a long time. It takes a particular kind of darkness to bring it out. It tends to emerge in times of major generational shift. The Obama-Clinton race seen from ten or twenty years in the future won't be about race or gender or politics in the usual sense, it will be about age. If Obama is elected, the people who will vote him into office are going to be very young, and they will be voting for the first time. The number of people turning up to vote in the Democratic primaries this year are unprecedented and are vastly greater than the number of people turning up to vote in the Republican primaries. Something's going on; I think it's probably a generational shift. Not that the '60s are coming back, God forbid, but it might be another version of that. And of course, that had a lot to do with what Norman Cohn was writing about, too.

UG: Cayce, the hero in Pattern Recognition, talks about paranoia. In Spook Country, when Milgrim is kidnapped, he doesn't have any idea what's happening to him, which is the paradigmatic paranoic incident. Nevertheless, in your book there is an almost materialist reading of what is happening in the world. To me, it seems like an anti-conspiracy theory.

WG: Conspiracy theories are popular and I suppose, for some people, absolutely necessary because they invariably posit a world structure that is immeasurably more simple than the actual structure of the world: It's all bad, because the Jews are behind it. It's all bad, because the Illuminati are behind it. It's all bad, because the Americans are behind it. That sort of thought reduces anxiety in people and that's why it's popular. They accept this really intellectually infantile version of the complexity of the world. Conspiracy theory provides some of the comfort that religious doctrine provides, but it's simpler. I don't think there are any bodies of conspiracy theory I adhere to, although I am fascinated by the phenomenon. One of my friends in New York has a fabulous collection of conspiracy theory material, going back into the 19th century. For instance, he has a book that proves that Dan Rather was behind JFK's assassination, because as the author says, he was in Dallas that day! That's a great book, it's bound in black rubber electrician's tape.

UG: It's self-made?

WG: Yeah, it is a treasure.

UG: In Spook Country, the net is introduced in a quite specific way; it is somehow turned inside out and projected into real space. You have invented a new art form for that purpose called locative art. For example, you describe a virtual monument on the site of River Phoenix's death. Why did you choose to write on GPS?

WG: I wanted a way to visualise the extent to which something has changed since I started writing about information technology. When I coined the word cyberspace, cyberspace was there, and everything else was here. That has reversed itself over the course of my writing. I literally think that cyberspace is now here, and a complete lack of connectivity is now there. If we could see the wireless exchanges of digital information taking place around us, we would be living in a much busier visual landscape. Most of what we do as a society we now either primarily do digitally, in what we used to call cyberspace, or we simultaneously do digitally and in the physical world. If you are driving with a GPS system, you are simultaneously driving your car and manoeuvring your car through a digital construct. I believe that very few of us are aware of the extent to which that has already happened, and I suspect that I'm not aware of it to anywhere near the real extent to which it has happened. So in this book I was looking for a more or less imaginary emergent technology or art form that will allow me to simply bring that up. The conversation in the coffee shop on Sunset Boulevard is a little more grandstanding than I usually do. I don't think I have had a scene in a novel before where three people sit down and basically talk about a William Gibson novel without ever really mentioning it.

UG: It seems that migration is a very important issue in Spook Country. Is this just a typical phenomenon nowadays or is your interest also inspired by your personal history? You were avoiding being drafted when the Vietnam war was going on.

WG: Well, I've lived my life in Canada without ever actually having been drafted. There was never a problem with going back [to the US]. I didn't have to apply for amnesty, or accept the subsequent pardon, that my actual draft-dodger friends all accepted. In fact they all went back. So staying in Canada in that situation is probably the mildest and most homeopathic version of the expatriate experience that an American can have. It's like an hour away. If I need to know what it feels like, I just go down to Washington state and go to a mall. There's a lot of migration around. There are a lot of displaced people floating through my media world today. You see them all the time. And I think I identified with misplaced people pretty much the day I was born. I don't know why, but I didn't need a harsh exile to Canada to get there. I don't know what that was. As a child, I can't ever remember feeling that I fit right in.

UG: You have, perhaps, been the central figure of cyberpunk. How important was punk for you, when you started writing in the late '70s?

WG: I was too old to really be part of it, but I enjoyed the phenomenon of not only the straight world, but also hippie parents being stunned by another new wave of rock'n'roll. ‘How can you listen to that junk?' The irony of that wasn't lost on me. Quite a lot of the music I enjoyed immensely. It was a very rich time for pop music. Although the stuff that I liked the most from that period isn't the stuff we now remember as being the canon of punk. I don't think Patti Smith is going to be remembered as part of punk for example, but she was there, and I loved what she was doing.

But what it enabled me to do, and what probably wouldn't have occurred to me otherwise if 1977 hadn't happened, was that I was able to import the attitude into the genre of Science Fiction. That attitude was so perfectly counter to what I saw happening in the mainstream of the genre that it couldn't have been more perfect for my purposes. It wasn't that I wanted to tear the genre down, but I wanted to return it to something of my idea of what it had been when I was 15 or 16 years old, which had been my heyday for reading Science Fiction.

UG: Would you describe the works of William S. Burroughs, who has obviously been very important to you, as Science Fiction?

WG: The biggest influence on my writing has been the accidental fact that I discovered the Beats and Science Fiction more or less in the same season when I was about 14 years old. I suspect that was fairly unusual. When I first tried reading Burroughs I didn't get it at all, but I recognised that there were elements of the genre of Science Fiction there. I thought it was the strangest stuff I had ever read and I knew that it had hit notes that nothing else had ever hit. Before I started writing, I gradually realised that a lot of the Science Fiction writers that I had admired in the '60s were copying from Burroughs big time, but Burroughs had been able to sustain those notes longer than anyone, and hit stranger highs. When I started writing myself, I had that as part of a toolkit that I knew I could appropriate. I appropriated in the opposite direction. Burroughs was appropriating Science Fiction, mysteries and pulp thrillers into avant-garde fiction and I was appropriating elements of avant-garde fiction quite freely into a sort of late 20th century Pulp Sci-Fi..

UG: How important has punk been for your style, which is very reduced, almost minimalist?

WG: I do a lot of revision. And most of the revision I do consists entirely of removing things. I think I used to be more anxious about that, because I had the understandable anxiety that if I took those words that I worked so hard on out, then my manuscript would be that much shorter and I may never be able to finish the thing. As I've gone on, I have become better at affording myself the luxury for weeding the garden a bit more.

UG: Marketing is very important in your books, more precisely the fact that every subcultural movement today is instantly detected, analysed and commodified. In an interview, you have said that it's hard for every bohemian subcultural movement to develop because it is harvested so quickly. Is that concept dead?

WG: I don't know. Bruce Sterling convinced me a decade ago that bohemias were the dreamtime of industrial civilisations, that they are a function of the modern project. But if we are now in some postmodern state, are bohemias still valid? Can that still happen? I don't actually know. We maybe passed that. It doesn't mean that there will necessarily be an absence of the things we associate with bohemias, in fact it may mean that there'll be more of those things distributed more evenly through society. It may not be possible in this sort of massively distributed marketing-based world in which we live for people to form those clubby bonds of old school bohemia with other people of like minds. It may just not be there. But it's not there in the respect that the people don't have the receptor sites in this society for that sort of bonding. It's just that we have changed in ways that we don't fully appreciate.

UG: One idea of bohemia is that you have to be secluded for a certain time and form your own social universe, which develops its own language. So what is fascinating today is that, on the one hand, the cyberleft is fighting against the fast reduction of privacy, but on the other hand, the younger generation has no problems with revealing masses of intimate information about their own lives online. How much and how radically do you think this movement is changing our societies?

WG: I don't know. I think I am too old to get it. It is like a kind of hypothetical construct for me. I think that is the fate of being a Science Fiction writer; if you keep doing it long enough, the world around you will become something you don't understand. But that's also the fate of all humans really. If you persist long enough, you'll be living in a completely incomprehensible construct of reality.

Ulrich Gutmair <supertxt AT zedat.fu-berlin.de> has been a reader of William Gibson's novels for about 20 years. He lives in Berlin where he works as an editor for the daily newspaper die tageszeitung

Info

William Gibson, Spook Country, New York: Penguin Putnam Inc, 2007

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com