Nuke It, Or We Go

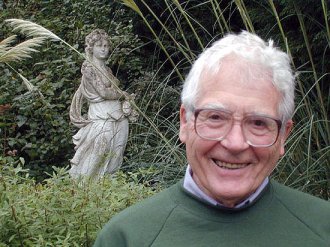

If his controversial Gaia theory claimed to offer a holistic vision of planetary self-regulation, James Lovelock’s answer to global warming is anything but. Advocating a return to nuclear power, energy isolationism for Britain, and meat cultures grown in vats, his theories sound more cold war than new age. Interviewing him this January, novelist James Flint sampled the fall-out from an avenging Gaia

It’s rare that a book gets a three-page splash in a national newspaper, especially when that book hasn’t even been published, and especially when it’s a pop-science book. But that’s exactly how The Independent treated the news that James Lovelock, originator of the famous Gaia Hypothesis of planetary self-regulation, had written a new work, (The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back – and How We Can Still Save Humanity), arguing that it’s already too late to stop global warming.

Lovelock compares the current situation to the 1930s, ‘when we knew that war was imminent, but there was no clear idea what to do about it,’ and draws an unsettling parallel between Kyoto and Munich, arguing that both conferences are characterised by politicians choosing appeasement over action in an attempt to buy themselves time.

Lovelock, who started his career as a medical researcher, is the author of more than 200 scientific papers on various subjects, as well as three previous books expounding his theory that the Earth and the biosphere actively combine to create and maintain the conditions for life. He has held numerous posts at universities in the UK and the US, is an Honorary Visiting Fellow of Green College, Oxford University, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and was among a select group of scientists called upon to advise Margaret Thatcher’s government on climate change.

He is also the man who, of late, has most upset the Green movement in Britain. Arguing that nuclear power is the only solution to the situation we find ourselves in, the scientist, now 84, has alienated Friends of the Earth director Tony Juniper, a long time ally, and prompted The Ecologist’s editor Harry Ram to describe him as having ‘lost it completely’.

So has the Green guru really gone mad? Or is he the Churchill of climate change, a sane voice in the wilderness? I went to a small hotel in Kensington to meet the scientist and his wife, Sandy, and munch my way through a large portion of home-made fruitcake in an attempt to find out…

JF: Is Gaia a metaphor?

JL: Well it is a metaphor, but it’s also an existing planet, and there’s nothing much more solid than that! You see, when scientists talk about metaphor, it’s a dirty word. But you can’t convey science to intelligent non-scientists without using metaphor. The only other way of doing it is by using the language of mathematics, but that’s not a common language by any stretch of the imagination. Not even amongst scientists. So you’ve got to use metaphor, and it’s just silly to attack Gaia on the basis of it being just metaphor, because dash it all, so is the Big Bang. So is the Selfish Gene, if you think of. I mean if you think of it it’s ridiculous, the idea that a gene could be selfish. It’s all metaphor. You have to use it.

But it’s not just non-scientists you need to talk to. Science itself is so separated into non-communicating disciplines as a result of the centuries of reductionism that scientists don’t even speak to each other. Do you know on my last count there are over thirty biologies? And some biologists are almost proud they know nothing about the others! You ask a molecular biologist about haematology and they’ll say that’s not my subject, I don’t know anything about that. And ask a few ethical ecologists about bacteriology, they go oh, no that’s not my field, that’s all medical stuff. And vice versa. So how the hell can a solid state physicist talk to a cryptogenic botanist? The whole thing becomes ridiculous. So I had a big job acting as a translator between all of these disciplines, because Gaia includes everything, from astronomy to zoology inclusive. It was necessary to do it and, as I think I found in my first book, there was only one way.

And I got this sort of cross-disciplinary apprenticeship because I was an instrument maker, and if you have an instrument it allows you to cross over all sorts of disciplines. And I thought, that’s wonderful! You see the first time I got to know climatologists, it was because I had developed a method of labelling an air mass, allowing you to follow it right the way across a continent. And then all the climatologists sort of came out of the woodwork. ‘Oh jeez, we’d like to talk about that, can we use it in our big mass transfer experiment?’ And you soon get into climatology then, because they accept you as one of them, and you pick up their jargon and so on, and before long they start treating you as if you were a qualified climatologist, which I’m not. And this is true of almost any branch of science.

JF: Reading the book I felt that part of you wants to bridge the gap between science and religion by creating a symbol or a conceptual space into which people can invest the same fervour and enthusiasm with which they currently invest the idea of God.

JL: Well if that’s what you’re going to say I’m just lost in admiration, because that’s what I have been trying to do all along, yes. You’re quite right. It’s not that I want to make it into a religion, God forbid, I’m a scientist. But people, humans, just as they need metaphors to understand things, they need certainty. It’s how we’re made. It’s why cognitive dissonance is so acute: we want to be sure about things. And religion does that very well, it has a purpose. And as you note, I try and get the Christians and the Muslims and so on to say well, look at the Earth as God’s creation. You wouldn’t want to damage it would you, it would be a sacrilege? And if people want to go further and worship it, who am I to stop them?

JF: It took a long time for the scientific community to take the theory up, though, didn’t it? It was tarnished with the ‘New Age’ brush for some time.

JL: It’s been quite a struggle. Well we’re traditionally still in the Cartesian world, aren’t we, when it comes to thinking of cause and effect?

JF: Do you think you’re finally getting recognition?

JL: Oh, plenty of recognition. In fact in 2001 there was this giant meeting in Amsterdam with scientists from all sorts of places, and they issued a declaration – the Amsterdam Declaration. And its first bullet-point was more or less the endorsement of my theory.

JF: So that must have felt quite vindicating.

JL: That’s right. The Geological Society is giving me their chief medal this year. And they don’t do that unless you’re regarded as kosher. To be fair the climatologists supported Gaia right at the beginning, and they have continued to do so right the way through and have continued to use it in their models. But the biologists have been in a bit of a battle with somebody or other almost ever since they started, and they just thought they’d won their battle with Creationism when I came along. John Maynard Smith, a leading biologist, told me that the reaction to Gaia was ‘Oh God, no, not another one’, so they wanted to trash it. And they sent their Rottweiler, Richard Dawkins, to do it.

JF: He’s their attack dog, isn’t he?

JL: That’s right. And up to a point it worked, because it scared the rest of the scientists away from it. But it was worth it. All theories have got to go through a rough time, the rougher the better. And that was what led me to make Daisyworld. I’d never have done that if hadn’t been for Richard Dawkins’s absolutely good argument that nothing can control anything beyond its phenotype.

JF: What is Daisyworld, and why is it so important?

JL: Well you see in answer to Richard Dawkins’s question, I thought I’ve got to show somehow that organisms living on a model planet can regulate some variable, and temperature was the obvious one because it’s not difficult to achieve. And it was fairly straightforward to think up dark and light-coloured daisies. The dark ones would absorb light and make the planet warmer and the light ones would reflect it and make it cooler. Just let them compete for growth and, using standard biological equations, no fudging, bung in all these astronomical equations about energy balance and so on, and bingo, you’ve got it. And I was astonished when I put it together in a computer and out it came: perfect regulation. And for a big wide range of variables. It was a real joy, that. Quite a thing to happen.

JF: In the terms of that model, why are algae so important in Gaia?

JL: Because they regulate climate in two ways. One they pump down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, they tend to keep it low, and the other way is that they produce a gas – dimethyl sulphide. Without that gas there would be no clouds, and the earth would then be a hell of a lot hotter because clouds reflect sunlight.

JF: I rather like this image you return to two or three times, of Gaia as an old lady, ready to evict a group of teenagers from her house.

JL: I’m sorry! It’s a bit silly. But I feel it gets over to the reader the situation we’re in.

JF: So my question is: is it too late? Has the eviction notice been served? Have we passed the threshold?

JL: Yes. I’m almost certain, or as certain as a scientist can be. Because things could still happen. We could get a sequence of volcanoes that blew up one after another, and that could set things back, though it would still leave the Earth in a bloody mess. But not only would that not answer the problem, it’s not the sort of thing that’s going to happen, it’s so remote. No, we’ve passed the threshold, alright. And even the scientists are beginning to say so now.

JF: When do you think we passed it?

JL: I would reckon some time in the mid-90s, perhaps before that. The clincher, of course, is the phenomenon of global dimming. I don’t know if you noticed the news yesterday saying temperatures only have to rise 2 degrees and the melting of Greenland becomes irreversible. Well, the climate would be 2.5 to 3 degrees warmer if it weren’t for the atmospheric haze produced by pollution. And once there’s an economic downturn and humans start dropping out, then that haze goes in a week, and you’re 2 to 3 degrees warmer immediately. So if we’re not past it, it’s just held in abeyance. But there are other factors, like the melting of floating ice in the arctic. And that’s likely all to be gone in thirty years. And that’s really dramatic, when you think about it. You could take a sailboat to the North Pole. And when you think of all those explorers struggling to reach it…

JF: And you think that’s really going to happen?

JL: Well last year you could circumnavigate the whole of the polar ice.

JF: For the first time, without an icebreaker?

JL: Yes.

JF: So what do you think then of the government report that was released yesterday, that we’re on target with renewables?

JL: Typical rubbish. I may be wrong, maybe I’m looking for conspiracies that don’t exist, but I see our current government as populated on the environment side by old CND members who used to march to Aldermaston. And their great dream was that if there could only be a nuclear-free Britain, all would be well. And they will do anything to ensure that that happens. And they know jolly well that they’ve only got to hang out another year or two years and all nuclear activity in Britain will cease, because it can’t carry on without support. So that’s their motivation. What they say of course is rubbish. There’s no way you can solve our problems with renewables alone. It’s not that renewables are bad per se – in some parts of the world, like Saudia Arabia, it would be a splendid idea to use wind-turbines for desalination on the desert shores.

JF: And solar power, presumably, as well.

JL: Yes, quite. But to use it in a densely populated small island where the countryside is truly treasured, that would be complete philistinism of the worst kind.

JF: So you are very anti wind-turbines.

JL: Yes I am.

JF: But part of this does seem to come from, if you’ll excuse me saying so…

JL: From being a nimby.

JF: Ha, yes, and I know that you address this in the book, but the fact is that it’s still there slightly, you do have a slightly precious view of the countryside and the way it’s used. And I felt that weakened your argument against wind-turbines a little bit.

JL: It may well do. Some of the emotional urge to write that book definitely came from the thought that they were going to put up one within a couple of miles of where I live. And I thought, ‘To hell with that’! But if they really worked and they produced power usefully, I’d grit my teeth and bear it.

JF: But do they not?

JL: No! It’s all lies.

JF: Is it?

JL: Yes. Because if you were, to take an extreme case, to try and take all the electricity in Britain from turbines, you would need about 250,000 of them, and they would be biggies, 1 or 2 megawatt ones, all over the country. And the problem is that the wind only blows 25% of the time. So you’ve got to back them up with 75% fossil fuel power stations. So what are you gaining? Well the government is not so mad to try and get all our electricity from wind turbines, but they hope to get 20% of it, and get the rest of the energy from Russian gas. Well this is quite insane. If Russians turn off the tap and there happens to be a big anti-cyclone like now, tough luck. We’d collapse.

Not only that, but the young radicals, like we all were when we were young – I was the same as the rest of them – how can they support an industry which is almost run as a scam? If you check it you’ll find quite a lot of the companies involved in this operate from the Cayman Islands. But they’re running off subsidies from our taxes. And yet they’re operating under conditions where they can escape tax. Nobody operates from the Cayman Islands except to escape tax.

JF: So you think they’re more interested in the profits and the tax gains than the wind farms?

JL: Of course they are. They wouldn’t exist without the subsidy. There’s some dirty work going on.

JF: Again there’s an interesting crossover here. One of the German authors of that government renewables report was saying it’s all very well talking about nuclear replacement in stable democracies, but to turn the planet over to nuclear is a crazy idea, and wholly unrealistic given the international political situation.

JL: No, I wouldn’t suggest that. I’m talking about us. I mean the UK. Not even Europe.

JF: So you say the nuclear solution is a UK-specific solution?

JL: Exactly.

JF: So what you’re actually advocating is a kind of energy isolationism, to prepare for the oncoming storm of…

JL: Well soon the supply of fuel from abroad is going to be completely disrupted, by the time things get bad. Well even last year it only took hurricane Katrina to bung oil prices up like a rocket. And that’s just the first baddie of that type that’s going to happen. And it’s going to apply to food, too. We’re going to be thrust back on our own. Everywhere is. And so all I’m trying to do is to make recommendations for keeping civilisation going on these islands.

JF: So what about the rest of the planet?

JF: So what about the rest of the planet?

JL: There’s nothing we can do about it. Because whatever we do, whatever gestures we make, it isn’t going to move the Chinese one bit. Or the Indians. Or the Americans. Or the Russians.

JF: For me the point where I became very frightened by the realisation that global warming is going to happen is the point at which I realised that the Chinese were all buying cars. And there’s no political power in the world that can stop that now. Not without a total economic collapse.

JL: I’ve got a friend who’s an advisor for the Chinese government, and they say, ‘Look, we’ve got the toughest, most rigid government in the world. But they know that if they hold back the aspirations of our people just one jot there’d be a revolution and they’d be out tomorrow. And if they can’t do it, how the heck can you do it?’

So it’s not a lack of willing or understanding on the part of the Chinese. It’s just practical politics. Our government lives in a dream world. They think that by signing Kyoto or something they’ve got a load of brownie points with Gaia. This is rubbish.

Anyway we’re past the point of no return. If we all suddenly said, great, the penny’s dropped, we’re not going to burn another ounce of fuel, the first thing that would happen is the temperature would rocket up two or three degrees as the dust went out the atmosphere. So why renewables?

JF: Okay, well let’s say that you’re right. Can we afford to build nuclear power stations here? They’re extremely expensive.

JL: What I’m recommending is not building new nuclear power stations at all. There’s nothing wrong with the existing ones. They merely need new reactors in them. And some of them could even be upgraded to last another 20 or 30 years. So let’s say perhaps a half to two-thirds of them need new reactors, and the rest could be improved and left running. Everything is there, the cables run to the grid, the planning permission’s been done. This is the obvious thing to do. And that is all we need. We don’t need to build more of them, because once the crunch comes we’ll bloody well have to live on the electricity they produce. And we will. It’ll keep the lights burning and all the essential services going, just as it did during the miners’ strike.

And this is an asset to the country that is crazy to throw away. How mad the government are is shown by the fact that the green members say, on the one hand, oh, you can’t rely on supplies of uranium, it’ll be very difficult to get and maybe impossible, so what’s the point? But at the same time they’ve announced they’re going to spend £6 billion decommissioning the 110 tonnes of plutonium we have in this country, which is a perfect nuclear fuel. It’s worth something like £160 billion worth of oil or coal, and it would keep the power stations going for ages. Madness.

JF: Can they be adapted to run on plutonium?

JL: Oh yes. The MOX system is mixed uranium/plutonium fuel. And it’s not the kind of thing terrorists can pick up and make bombs with either. It’s got the wrong plutonium in it, anyway. The whole decommissioning thing is insane logic. They’re going to spend £60 billion decommissioning. Why decommission them? Keep them going!

JF: But if the sea levels are rising, aren’t Sizewell and Dungeness in danger?

JL: I asked the people at BNFL about that, and they said yes it would be a problem, but they thought they could get round it with levees and things. We’re talking about keeping them running for 30 years or so, by which time things will have got so bad we’ll have other, bigger problems to worry about, or fusion will be available.

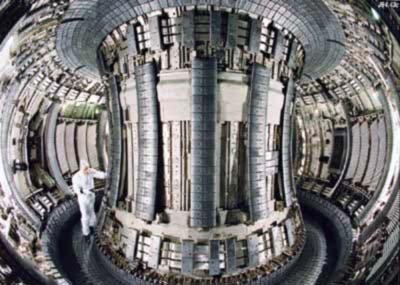

JF: I went to the UKAEA Culham website (www.fusion.org.uk), and saw that they’ve managed to successfully sustain a two second burn on the fusion flame, which is a big breakthrough. So tell me more about that.

JL: Okay well the physics have been largely solved for fusion, and it’s largely an engineering job now. The one at Culham could be producing power but it’s too small. I went there and was taken round. It’s a remarkable thing. It’s almost eerie. You’ve got this torus in which they do the reaction, and yet inside it the temperature’s hotter than the middle of the sun. 150 million degrees Celsius. Even school physicists know that the radiation from a hot body goes up as the fourth power of its temperature. I mean why isn’t everything fried for miles around it? And the answer is, of course, that there is almost a space vacuum, inside it.

JF: It’s held within an incredibly powerful magnetic field, is that right?

JL: Yes. The whole thing is wonderful, really. And there’s a great lot of enthusiasm there. And I meant it when I said that if they’d spent the money that they’ve wasted on wind turbines encouraging fusion, then they’d be laughing.

JF: What about nuclear waste?

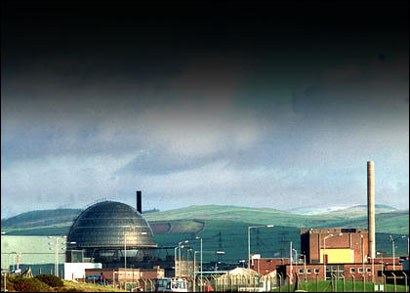

JL: Oh nuclear waste, I’m glad you mentioned that. We went to Sellafield just before Christmas, we were taken there by the Prospect trades union. And they let me take my own hand-held radiation monitor. It was fascinating. It’s quite a pleasant site. I thought it would be a horrible industrial place, but it’s really very pleasant, in a gorgeous setting, you can see the Isle of Man across the water and the Lakeland hills behind. All the way round – and we went round the whole site, every bit of it – and the radiation levels were about the same as they are in London. But about a third of St. Ives, in Cornwall.

JF: Well there’s all the granite in St. Ives, which gives a high background dose. Granite has a high uranium content

JL: Yes, that’s right. So Sellafield was really quite clean. Only in one place did my monitor give high readings. There was a building which was fairly big – though it would’ve fitted into most small-town industrial parks – with sort of corrugated sides, and they pointed it out saying that in there was stored all forty years of our high level nuclear waste. Plus quite a bit of Japanese and other waste. And around the edge of that building the level was one microsievert per hour, which was 40% greater than a typical street in St. Ives, but one third of the EEC lifetime radiation level.

JF: Well okay, but I’m quite suspicious of this. I know that Sellafield is fine, but whatever they say there’s a lot of waste sitting in ponds…

JL: Where?

JF: Well at our various nuclear facilities. There’s a lot of waste sitting in ponds with nowhere for it to go. We have no long term depository in this country. You can’t sit it above ground in Sellafield for 10,000 years.

JL: Why not?

JF: I don’t know. Maybe you can?

JL: What’s wrong with that? If it were mercury it would last forever, and it would be a major problem, an enormous big pile of mercury, because it can vaporise and cause all sorts of trouble. That radiation is dying away all the time.

JF: Yes, but very slowly. Some of it is poisonous for 100,000 years.

JL: Only if you swallow it. The Finns are much more sensible than us. They just bury their waste in granite. Their argument is within a few hundred years the radiation levels will be the same as the granite, so why worry. The Greens tell absolute lies about nuclear, they always do.

JF: Perhaps. But the other place that’s out of sight and out of mind is uranium mines.

JL: Oh I couldn’t agree more. Terrible things, and often badly run in bad parts of the world.

JF: Yeah, with of lot of workers dying, not just of radiation poisoning but silicosis and all the rest of it.

JL: That’s right. But, you have to remember, and this is one of the great things: I once asked BNFL why don’t you put whole page ads in the press saying how good nuclear is, because the safety record is very good, actually. For Britain it’s wonderful. And they said, we can’t afford it. And then the penny dropped. Because the throughput of uranium is 1/2,000,000th of the throughput of oil. So it’s a tiny amount. And the same is true of the waste. It’s a tiny amount, for the energy involved. And everybody forgets the CO2 mountain.

JF: Which is a point you make very well in the book.

JL: Yes, and that’s huge – and it’s going to kill us all. So why fret about something that’s not doing anybody any harm.

JF: Presumably even if we go the nuclear route a combination of nuclear and renewables is a good idea?

JL: It’s a better idea than a combination of renewables and gas. Because renewables’ vast weakness is their intermittency. Nuclear is dead steady. Tidal power is a very good idea, but it’s just so slow. It would take 20-30 years to implement.

JF: Why so long?

JL: To do anything on a big engineering scale takes about that. And that’s if you’ve got a full plan, and you’re starting now. It just drags out.

JF: And presumably rising sea levels would disrupt those mechanisms anyway?

JL: Well I think they could get round that. I’ve long thought that the Severn barrage should have been developed. And it would have been, if it hadn’t been for Green objections to it.

JF: Could it have messed up the ecosystem?

JL: So they said. But nothing like as much as the windmills will.

JF: Do you not think, though, that although renewables may only make a small difference, they have a political impact in that they get people to think much more seriously about the environment?

JL: I’ll give credit to that. But the term ‘renewable’ is daft in itself. Burning petrol is perfectly renewable. It’s just the rate at which you do it, which makes the difference, because the Earth is burying carbon. As long as you don’t burn it at more than the rate at which the Earth is burying it, you’re fine.

JF: But solar power… you could argue that if all the money spent on nuclear in the 1970s had been put into solar, we’d all be living off that by now.

JL: What, in this country? I think there’d be a problem in winter time. It’s not practical. There’s just been a big article in Chemical and Engineering News, one of my favourite American journals, saying what a pity solar power’s still not economic, after all these years. They had a graph showing dropping costs of doing it. And it just levelled off. Even with the best engineering. And unless there’s some amazing breakthrough we’re stuck at this particular number of dollars per megawatt, I forgot what it was.

We saw a house at CAT [Centre for Alternative Energy, http://www.cat.org.uk], a nice place, a lot of enthusiasts running it, and they told us that the roof which had solar cells on it and gave, I think, 3kw of energy, cost as much as the house. Now how’s the average punter going to run on solar power that way? It’s a lovely, visionary idea. But it’s just not practical.

JF: Two last questions… Why is organic farming – and farming in general – such a problem? You’re growing food. Isn’t that green?

JL: Well the whole point about Gaia, which the Greens do not understand at all, is that in order for the planet to stay regulated it needs its natural ecosystems to do their job. We keep on knocking them down to make farmland or furniture or build houses. And it won’t do. As much of the global warming that’s happening at the moment is due to land use as it is to emissions. And to think of using land for biofuels is the maddest idea I’ve ever heard.

JF: You talk a bit about a future in which we synthesise food. How would that work?

JL: If you’ve got a lot of energy – from fusion say, because we’re talking about a long time in the future – then you use it to synthesise simple feedstock, amino acids, sugar and whatnot. It’s straightforward chemistry, as long as you’ve got lots of electricity. And you use that feedstock to feed big tanks in which you’ve got cultures of lamb, beef and so on. You’d never stop them genetically modifying it, mind you! I tried this out on Shell once, at their headquarters in Amsterdam, and it was funny, these old chemists around the table, they got so wildly enthusiastic. Ah, they said, that’s where the future is! We’ve got to do this, just think of it! Think of the economies of scale! Here we are at this big plant, making fertilisers and sending them all round the world, then bringing back the beef and all the rest of it. We could do it all here in the same factory!

JF: Let’s face it, it’s preferable to battery farming chickens, isn’t it?

JL: It’s an evolution. We’ve developed battery farming, which is awful, but through it we come out with synthetics. We take a few chicken muscle cells, you’ve got to sacrifice one chicken, for that. Or maybe you don’t – just take a biopsy, through a needle, and from that you grow up your great big vat of chicken breast meat.

JF: And this is what your Chicken McNuggets and microwave meals get made of? Which is pretty much what they’re made of anyway.

JL: It might be better!

JF: Why, because you’re not pumping the flesh full of pesticides and anti-biotics and so on?

JL: You’d have to grow your tissue culture under highly sterile conditions, just like when they make antibiotics – or brew beer. The chemistry is very similar. The brewers are damn sure they keep their brewing vats very clean, or the beer would taste bad. It’s well known technology. It’s not so visionary.

JF: Why does it take so much energy?

JL: Ah, that’s the problem. You’re taking carbon dioxide from the air, you’re taking nitrogen to make the protein, and water, and reacting them to make sugars and amino acids. The energy coefficient is positive, so you have to use energy to drive it. It wouldn’t take all that much in global terms. If the whole world, that’s six billion people, were fed on it, it would mean fixing half a gigaton of carbon every year. Which is quite a lot. If it was just done in the UK, where we need it more than most because we’re so densely populated, it would be 2% of that.

JF: Where does the electricity go?

JL: Well, the energetics, you can look it up.

JF: Well I think that’s answered all my questions.

JL: Well they were jolly nice questions. Quite a good discussion.

JF: Excellent fruit cake.

JL: Sandy’s a real wonder at that.

Interview conducted 31st January 2006

James Lovelock, The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back - and How We Can Still Save Humanity, Allen Lane February 2, 2006

For a very different perspective on calls for energy isolationism see M29 Peak Oil and National Security: A Critique of Energy Alternatives by George Caffentzis

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com