Notes on The Last Days of Jack Sheppard: Capital Crimes and Paper Claims

Extrapolating from his talk on Anja Kirschner and David Panos’ recent film about 18th century folk legend Jack Sheppard, Benedict Seymour traces the intimate relationship between death, representation, fiction and speculation. Then, as now, the attempt to escape from capitalism’s calculus threatens to collapse into another moment of capture

It is as reasonable to represent one kind of Imprisonment by another, as it is to represent any Thing that really exists by that which exists not.

– Daniel Defoe

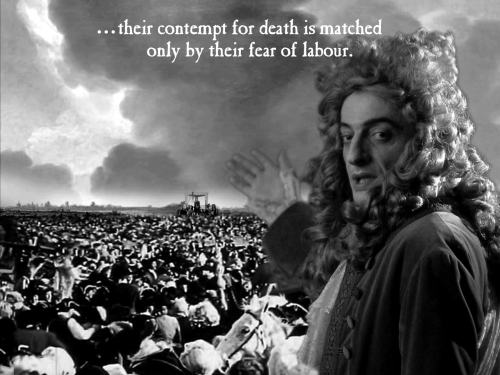

Image: still from The Last Days of Jack Sheppard

The Last Days of Jack Sheppard (2009), directed by Anja Kirschner and David Panos, retells the story of a proletarian hero of the early 18th Century who ending his days at the gallows – ‘the triple tree’ – in Tyburn in 1724, was executed for theft at the dawn of financialisation.

Jack Sheppard wasn’t much of a thief. Serially incarcerated during his short life, he won fame for his ingenuity and implacable dedication to getting out of gaol. This is years before Houdini, with his spectacularised escape artistry and proto-Fordist routinised liberation. It is years before David Blaine, who inverted the trope of getting free into feats of hyper-visible confinement endured. Jack’s very public demise is furthest from but for us also closest to the telematic death and redemption of Jade Goody, a working class woman who, like Jack, also found fame in dissolution.

Unlike Jade, however, Jack stood for a certain resistance to commodification and the intrusion of the State into one’s intimate processes of self-reproduction.1 Like her he rose to fame in the wake of a suddenly deflated financial bubble. The Last Days of Jack Sheppard plays on the interconnections between his acts of criminal reappropriation and the speculative adventures of the wealthy during the South Sea Bubble of 1720. As much as anything, Jack’s notoriety was about the contrast his crimes made with the legally sanctioned scams of his social superiors; his bravery, fortitude, skill and cunning versus his superiors’ petty self-aggrandisement and greed. Jack also remained independent of corrupting tendencies within his own class and refused to join in the rackets of Jonathan Wild, self-appointed ‘thief-taker general’.

For these and other reasons we will come to, Jack was one of the first heroes of popular culture. His ghost-written biographical Narrative appears as an early act of proletarian public speech. A posthumous publication, the Narrative is based on the words of a man condemned to death; a man escaped and recaptured who is given the right of representation only when he has nowhere left to run.

Near the beginning and end of the film the notorious housebreaker and escapologist (four times escaped from prison, four times recaptured) invokes his right to speak. He holds up the manuscript of his memoirs to the crowd as he stands before the gallows, a dialectical image of the decisive forces of his age. The scene brings everything together – capital and capital punishment, money and representation, the mob and their hero. Jack steps up onto the platform to have the last word, to give his own account and put right earlier misrepresentations. However, the film sardonically notes that this last gesture of self-assertion is already, also, a piece of advertising. Jack’s publisher Mr Applebee is at hand to tout the completed Narrative – ‘available for 6 pence only from Applebee’s’. In the background, as we shall see, there is the anonymous ghost-writer of the text, Daniel Defoe.

It may be considered a moment of resistance, a claim to rights that were not supposed to be issued to people of Jack’s class. As such it is also an attempt to use the bourgeois representational apparatus to get something material back – control over his own history and a legacy for his mother. This last raid on the emerging finance/culture nexus is carried out within the terms of the law and of the market. Like the stocks and bonds of the bankrupted stockjobbers glimpsed in the wreckage of the South Sea Scheme at the beginning of the film, Jack’s Narrative is itself a kind of ‘paper claim’ on value. Behind it lies a contract, and a title to sales revenue, but in itself the Narrative is a fiction, a projection of what his life will have meant. Furthermore, Jack is not the real, or at least the sole, author. The film’s diegesis continues and exacerbates the logic of displacement by putting into his mouth words that others would only have read on the printed page, pointing up the artificiality of the mise-en-scene and, by extension, of the public sphere.

Jack’s moment of free and direct expression, of the right to tell one’s story and give one’s own account of one’s self, is also the moment of commodification. Destitution recapitulated. Alienation consolidated by claims of complete transparency (Defoe’s vanishing mediation). The moment of truth is the moment of fiction, of a constitutive falsehood analogous to the wage labour contract in that it is both ‘authentic’, legally recognised and a kind of betrayal of at least one of the consenting parties. Jack becomes a virtual player in a textual construct, enabling us to retell and rework his story, but objectifying and distorting his necessarily open-ended subjectivity. Death launches him on the literary market. Analogies to paper money and credit here are not accidental: representation opens up the possibility of derivatives, variants, meta-fictions.

The act of representing one’s self – as the film explores – depends on just such objectifications, a process of displacements and substitutions which put the speaker’s identity and status (living/dead, rich/poor, etc.) in doubt. Jack breaks through the social repressions of his day to speak up for himself and, by extension, his class, but he is also spoken for. His words are put to work. The future development of working class struggle to escape from capitalism is foreshadowed here. The question is implicit throughout – how does the subject/object of history, neck in the noose and facing extinction (or perhaps the mutual ruin of the contending classes), get out of this one?

As in life, he had to alienate his considerable skills as a carpenter in the service of others’ accumulation of capital, so in death Jack’s voice is ventriloquised and exploited by Messers Applebee and Defoe for their own ends. Equality is the very form of inequality; the contract guarantees the subordination of the economically dependent and the reproduction of their alienation. Jack makes history, or at least his history, but not in conditions of his own making. And what will history make of him? The film is hyper-conscious of the potential and risks of myth making, yet in order to pose the question of Jack’s legacy, of his contemporary significance and indeed the future of his class, it is necessary to put him in the frame; the film has to borrow and trade on his legend.

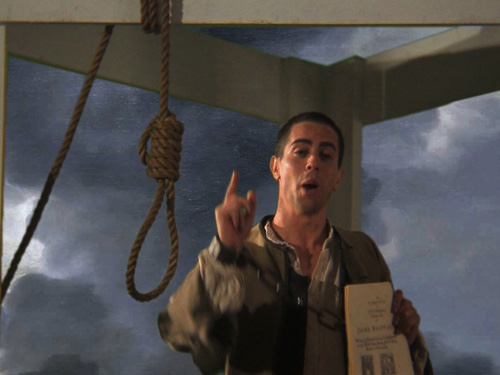

Image: still from The Last Days of Jack Sheppard

The early 18th century represented here is an age of ‘projections’, of new financial abstractions, schemes and scams, exerting an increasingly autonomous force in social life. Jack’s story, at once a critique of the self-contained world of the stock exchange, the Mansion House and the coffee house, is itself a highly mediated claim to authenticity, a work constructed by Daniel Defoe giving the illusion of a first person account. However, true to Jack’s own language and history, it is necessarily a work of (real) abstraction. For a growing market, Jack’s life has become a kind of ‘structured investment vehicle’, a spectacular commodity with an existence independent of the unruly mob who flocked to his hanging. In death, his social mobility is potentiated.

Jack’s rebirth (or undeath) as a literary figment and popular hero, like the floating of a new concern, is a hostage to the market and to the stories people will construct as derivatives of his ‘authentic’ paper representation. Once written down, he is no longer free to determine his story. The film itself is one such derivative, taking as its premise a hypothetical struggle between the Narrative’s two authors – the ghost writer and ghost-written, Defoe and Sheppard – over the content of the biography. By positing this ur-narrative or pre-textual struggle the film is able to reopen what the Narrative tried to close. It is a narrative back-projection which underlies and echoes the film’s other projections, its allegorical/art historical décor made up of prints, paintings, drawings and other artefacts from the period.

Long ago, Frederic Jameson identified postmodern culture’s ‘renarrativisation of the fragment’ as a kind of recycling, reinscription and domestication of modernist practices of disjunction. What distinguishes The Last Days use of parody from this form of blank referentiality is its heightened awareness of the economic determination of and struggle over signs. Where Jameson sees in postmodern culture’s abstraction and reflexivity an analogy to finance capital’s attempt to defer and get around the underlying tendency to crisis in capitalist production by proliferating virtual capital, this particular art work turns the logic of cultural looting in on itself. The result is an emphasis on the perpetual presence of economic relations of domination in capitalist culture tout court. The struggle between Jack and his literary representative is not a mere conceit by means of which to squeeze a new work out of an old one, an ‘exotic literary instrument’ that yields a domesticated and carefully captioned blast from the past. Instead it pushes renarrativisation into overdrive, offering a web of analogies and historical allegories.

By enquiring into the effectivity of signs, the performative power of fictions – economic, literary, biographical – the film is also alert to the way ‘paper claims’ function primarily as ways of appropriating the (rest of the) material world. Money is essentially a title to future value, a ‘licence to loot’ insofar as the paper titles to capital which capitalists deal in always project ahead of the world, ahead of existing value, through the process of capitalisation. Signs, however apparently free-floating and autonomous, tend to intersect in the most brutal ways with processes of accumulation, equivalent and non-equivalent exchange. Paper claims exact work and life from the labouring bodies they command. In the case of the film, the key moment being the separation of peasants from the land and the production of the urban proletariat of whom Jack is a part. Money, State and the banking system are results and, it should be stressed, products of the (perpetually renewed) dispossession of the poor from all independent means of subsistence. Paper claims are worthless without the State to back them up, and the projections of the financial elite are likewise predicated on a brutal ‘framing’ of the poor.

This brings us back to the triple tree. Execution is the most profound form of recognition which the ruling class can offer one such as Sheppard. It’s also, however, a way of negating identity completely. Capital punishment makes the criminal at once particular and equivalent. Use of the gallows was calibrated around the price of commodities, and hence the socially necessary labour time reappropriated by the malefactor and unreliably echoed in the (jurors’) estimate of the prices of the stolen commodities.2 But the gallows were indifferent to the arguments and aphorisms that a proto-literary figure like Jack was capable of (‘One file is worth all the bibles in the world’). Jack’s (illicit) claims are answered by his definitive transformation from subject to object – the inversion on which capitalism runs made horribly explicit. The ‘moment of [his] dissolution’ is the moment of his complete reification, and, with the help of Defoe and Applebee, the moment at which he gains access to the official means of representation, becoming the subject of a new kind of separation, a second order of (linguistic) enclosure. His death sentence and its execution opens up the space of representation, the dimension of fiction, fantasy, financial projections and speculative futures. Indeed, as we have said, Jack is ‘floated’ as much as hanged and his Narrative becomes the stuff of, or rather for, Legend. A story is born with the death of its protagonist, the Narrator (in the manner of a film noir such as D.O.A.) is already posthumous. Like Jade who survived to read her own obituary, there is something zombie-like about the public proletarian, not lacking in wit, far from wordless, but at the same time, as Applebee puts it, ‘doomed’. The sympathy of the public sphere for marked men and women is already, at this historical moment, the most suspicious thing about it.

There is something rather ‘aesthetic’ about this final instant, then. To quote one of the newspapers of the day, Sheppard was hung up and ‘dangled in the Sheriff’s picture frame’ for 15 minutes. ‘The sheriff’s picture frame’ makes clear the tacit connections between artistic and literary representation and the State’s repressive apparatus. Beyond any Warholian undertones, the link between execution and celebrity is not just via the struggles over the body of the malefactor, the crowd’s identification with the victim or the ballad sellers’ narration of their life and times. In fact, the gallows are aesthetic insofar as it constitutes a crude means for communicating a message to those that can read Jack’s broken body. The State itself requires notoriety to get its point across. This is spectacular language aimed at the (mostly illiterate) early proletariat. Not for them Jack’s ghost written Narrative.

The message is the imposition of work. Commodification uses death to communicate its imperatives to the living through the mediation of exemplary delinquents. As the film presents it, Jack is an escape artist captured first by the fascinated artists of the aristocracy (Thornhill paints Jack’s portrait while the felon is chained up in Newgate, shades of Fassbinder's Fox and his Friends, here) and then definitively by the art of the State. As Peter Linebaugh frames it in his great book The London Hanged, the triple tree was not so much the final stage for disposal of society’s ne’er do wells, as one of the foundations of the economy. Capital punishment was a part of the production and reproduction of the poor as workers, it was there to teach people a very definite lesson. Founded on the originary violence of primitive accumulation – the separation of people from their collectively held property through the enclosures – early capitalism attempted to instil in those that produced its wealth the necessity of toil. Those who refused to submit to the imperative of making their living by taking what they needed to subsist – or like Jack, flaunting a desire for luxury deemed out of his social reach, luxury beyond reason or measure – would be made an example of. The triple tree was the most important prop in a theatre in which the insubordinate were turned into the unfortunate protagonists of a cautionary tale.

Image: production still from The Last Days of Jack Sheppard, by Alessandra Chila

But the State did not have complete control over this stage or the stories told about it; both the criminals and the mob were given an opportunity by the very public nature of the spectacle. Jack’s speech in the film sums up the way in which the stage of instruction was being turned into a site of contestation, a place in which the poor might talk back and challenge the ongoing process of separation by which work was imposed.

Revolts at the points of instruction, punishment and incarceration were in turn providing the raw materials for goods in the literary market place, another node in the production and circulation of commodities. The spiral continues, from enclosure to escape, re-enclosure to re-escape, re-escape to re-enclosure. Remorseless, and contingent, one recalls Marx’s famous formula for the mutation of money into more money: ‘M-C-M’. Capital wants it to continue in a seamless cycle, but in reality there are many obstacles to valorisation – Jack is just one example.

During the course of the film the dialectic of representation gets turned around one way then the other. Defoe may have tried to make an example of Jack, a lesson that crime doesn’t pay, that corrupting influences lead him astray, or, more subtly and presciently, that within even the worst criminal there is a kernel of industrious ingenuity that, carefully harnessed, can and should be put to work for expanded accumulation. The film shows Defoe struggling to impose his sense of Jack’s story, to tell something more than a simple morality tale, or rather to invent a new morality able to move on from the dizzying loss of balance produced by the South Sea Bubble. Defoe is straining forward to something like Adam Smith’s conception of civil society, but remains confused and disoriented by the financially-accelerated rise of his own class – not to mention Jack’s. The film makes this drama perhaps even more central than Jack’s own (circular) narrative of incarceration and escape. If he could redeem the whore Moll Flanders and turn her into a kind of self-made woman, perhaps Defoe can reconfigure Jack as a post-Bubble figure of mis-directed industry.

Half the time Defoe is winning, half the time Jack. The film leaves the struggle open, but history suggests that Defoe’s successors did find a way to put Jack’s drive to exit (not to mention his right to a voice) to work. Defoe anticipates Adam Smith and Smith, both Marx and Keynes. All that’s solid melts into air, says a Frenchman surveying the ruin after the collapse of the bubble at the start of the film. But this ‘dissolution’ produced the new financial instruments, the perfection of the division of labour, the growth of industrial capitalism and the rationalisation of the working class, with the Socialist movement the most ambitious and contradictory form of integration. Today, both the bubble and the bureaucrats are in a state of collapse, yet, as the film’s less than exuberant mood implies, the proletariat has not yet found a way to get back on (and/or, off) the stage of history. Instead, they have a gallows look about them.

In this respect, Sheppard is a salutary reminder of the potential of working class insubordination, its ability to posit itself as a ‘self-subsisting positive’, not the negation of the bourgeois negation reproduced by the socialist movement. On the other hand, once one grants a certain autonomy to the working class, one has to acknowledge that capital, in our era, has been only too keen to leave the poor increasingly to their own devices. (At least when it comes to welfare provision; when it comes to surveillance, it’s another matter).

As Peter Linebaugh tells it in The London Hanged, Jack’s popular appeal was based on a shared experience as much if not more than symbolising some utopian return to a life before, let alone beyond, capitalism. Jack stood not only for the possibility of turning the tables on the owners of capital but for the daily escapology that the poor needed to practise in order to survive. According to economic historians of the period, the poor’s ability to subsist at all remains a mystery. Crime was not so much a deviation from the path of righteousness as an essential part of the daily journey of self-reproduction. Jack’s may be a story of freedom, as Peter Linebaugh says, but it is also about the way in which proletarian escape can and must itself become a part of capitalism’s continuation. One recalls Mike Davis writing in Planet of Slums about the contemporary form of this ‘wage puzzle’:

With even formal-sector urban wages in Africa so low that economists can't figure out how workers survive (the so-called low-wage puzzle), the informal tertiary sector has become an arena of extreme Darwinian competition among the poor.

To put it another way, the ongoing attempt to break the law of value, to live more than is allowed, is from the beginning, and again today, an increasingly central part of capital’s calculus. Rather than honouring the principle of equivalence on which commodity exchange is founded, from the beginning capital has depended on short changing those that produce and constitute value. Jack may have taken more than was deemed his due, breaking the principle of equivalence by running away with the means of production or stealing a silver spoon destined for the unproductive consumption of his betters, but capital also assumed – one could say it insisted – that people would find ways to exist and to labour on less than they were owed.

The film proposes a rhyme or homology between this early period of capitalism in which the wage was barely operative, before the stable establishment of capital’s rules, and our present moment in which the rules appear irreparably bent and in which a second financial revolution is collapsing into a crisis of unprecedented proportions. The process of financialisation is presented as co-existent with that of primitive accumulation, mutually reinforcing.

Jack’s birth as a fictional character coincides with a generalised fictionalisation of identity and a simultaneous dematerialisation and reification of its physical and linguistic props. As money replaces land and wealth is dissolved into economic representations, gold is displaced by coin and in turn paper, and ready money by public credit, the subject is (forcibly) liberated from the continuities and fixities of feudal society. As the film suggests, this involves the transformation of ‘character’ into ‘mere’ writing; myths of depth and substance are under attack, the self as a performance or improvised script comes to the fore. Finance itself is positioned as one of the key, possibly the key, solvent of feudal social relations. Those that today call for a return to a healthy, productive capitalism purged of speculation overlook not only the constitutive place of finance capital in any capitalism whatsoever, but also the way in which speculation is a necessary condition not only for modern thought but for modern praxis tout court. To be precise, for that material praxis which Marx identifies some 130 years after Jack’s pioneering efforts in excarceration. The apprehension that humans are the source of the value/s they live by, and that the reproduction of the world in its totality is down to our sensuous activity is the dangerous secret behind commodities such as Jack.

Thus, fictitious capital is an agent that not only produces a new fictitiousness and fluidity of identities but also, potentially, contributes to the volatility of social relations that makes possible the creation of new forms of life. The aristocracy grabbed the opportunities (and took the risks) which came from the rise in capital by mortgaging their land and creating a sort of trangenerational stipend, which was a life saver for a class in decline. The poor, however, were brutally separated from their own communal holdings of land and had to take back what they could through a process of imposed improvisation. Jack is a figure for the unmanageable excess generated in the process, an unforeseen by-product of a society governed by the imperative of capital accumulation. As such, his primitive challenge to capital is not so much a residue of the feudal era but a brand new product, yet to be mastered and, today, no longer subject to the dismantled and decaying apparatus of labour representation.

Image: still from The Last Days of Jack Sheppard

Capital has been dependent on breaking its own law of value in both eras, pushing to impose its terms of exchange and to hold workers to written and unwritten contracts while finding ever new ways to get around the iron equation between value and the socially necessary labour time for its reproduction. Corruption is not only the source of innovation (pace Bernard Mandeville, Adam Smith, Giovanni Arrighi and Antonio Negri) it can also be a sign of a system’s decadence. While corruption was the talk of the whole nation for much of the post-South Sea Bubble era, up to and including the appearance of Jack on the scene, the grotesqueries of non-equivalent exchange were only fully perceptible against the intimations of equality emanating from the very logic of the market. The aristocratic critics of capitalist greed deployed a feudal morality which they themselves found increasingly impossible to inhabit, while satirists such as Swift already noted the unfairness and cruelty of the new society, even as they hankered for a restoration of more stable forms of domination. In Jack’s day the dissolution of a stable hierarchical social order based on landed property is the most obvious and the most encouraging, result of the rise of financial and mercantile capital. Power was becoming visible, status and influence could be bought, privileges were being transmuted into more nakedly economic forms of domination.

Corruption, and the financial crisis released by the collapse of the South Sea Bubble, would become part of the movement toward expanded social reproduction which capitalists themselves (think of Thomas Malthus’ gloomy anticipation of death by horseshit) could hardly comprehend at this point. For all its intrinsic brutality, the imposition of the form of abstract labour on work just beginning in Jack’s day. This would see not only the rationalisation and disenchantment of social existence in its totality but the creation of the material conditions for hitherto unknown self-determination and abundance – given that the dispossessed reappropriate and transform the forces and relations of production. In our day, corruption and delegitimation seem to have undermined fixed authority and ensured the reproduction of a decadent system; both capital and its social democratic opposition (‘the left wing of devalorisation’) are discredited but the working class have suffered greatly through the concomitant process of non-reproduction.

Defoe’s scheming to imagine a way of putting Jack’s exuberance to work points toward both a new form of enclosure – from industrial production down to Fordist devalorisation through the supervision of every aspect of the workers’ reproduction — and a more rational form of social existence. By contrast those writing the working class’s scripts today are rarely capable of imagining a better world even in their own meagre terms. As such Jack’s moment rebukes our own; the social imagination fired by his escapes needs to be reawakened through modern day excarcerations. Although these may have to take apparently Blaine-like forms: occupations, refusals to move, the assertion of our rights in parts of the social factory that capital is now trying hastily to dismantle. Again, these rights will not necessarily be enshrined in law, and will involve workers crossing the line. Jack’s opportunism is also salutary. One can use the law, protect oneself where necessary, know the law better than one’s lawyers. But one will also need to keep alive a healthy sense of the law’s fictitiousness, its paper claims to a justice which can only be material.

The paradoxical message of Jack Sheppard’s fugitive art in an age of faltering globalisation and desiccating liquidity is that fixity and self-enclosure can be a tool of liberation; a first, if necessarily transient, step toward a greater excarceration. In the year of the Lyndsey and Visteon workers’ struggles, we are returned to the ambiguous legacy of the integration of the proletariat into structures of representation with a vengeance.3 While some dismiss any concern with the fate of the residual industrial working class as chauvinistic or narrowly sectarian, a fetish for manual labour or racist preference for defending the struggles of those with something rather than nothing to lose, it is worth considering how – like Jack on the gallows, facing death – the almost-posthumous workers of the world can also send out insurrectionary signals when they refuse to go gently into the lousy night. The Last Days of Jack Sheppard traces the implications of a valediction without reconciliation, the power of refusal in extremis as the beginning as well as the end of something.

Benedict Seymour <Ben AT Kein.org> is a writer and film maker. He is seeking funding for a video project on Bernie Madoff and Hollywood in the style of Godard's Histoire(s) du Cinema, working title: Forest Gump – Our Caligari

Info:

Anja Kirschner and David Panos’s film, The Last Days of Jack Sheppard, ran at the Chisenhale Art Gallery in London from 8 May – 21 June, 2009 and CCA Glasgow 8 August – 26 September, 2009

Footnotes

1 It could be that what was truly representative about Jade’s death was that it was an avoidable tragedy resulting from neoliberalised UK health care’s growing focus on policing behaviour over the treatment of illness. If her cancer had received the same attention as her subsequent demise (not to mention the ongoing saga regarding her moral status, etc.) there would have been no life-affirming, emotional franchise, no fictitious capitalisation on her death. Some would rather see the death-fest as a sign of our emotional evolution and progress (as with the manic mourn-in for Princess Diana) rather than an index of social decadence. However, though Jade’s death put cervical cancer check-ups back on the agenda for younger women, one should ask why they weren’t making regular trips to the doctor in the first place. Responsibility is shifted onto the patient and away from the ‘service’ provider/public-private State. The flip side of this contraction of social reproduction is a corresponding financialisation of death. Max Keyser notes that with the rise of entertainment futures trading there is now a corresponding spate of death rumours and death threats circulating as a result of ‘death speculation’ and ‘death pools’, as traders attempt to sell short Hollywood actors and other A(AA?) list stars. Market manipulation is spreading from the stock exchange to the entertainment industry as the crisis deepens.

2 'We observe a relationship between 10d. and a whipping, between 4s. 10d. and a branded hand, and between large sums of money and a hanging … they are only imagined figures of account [... but …] the consequences of these sums upon the bodies of the offenders were very real.’ In Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century, Verso, 2003, p. 82.

3 As so often, union representatives have played an at best ambivalent role in the current conjuncture. Though union members and shop stewards made much of the running, particularly in the mobilisations around the Lyndsey refinery wildcat strikes, union convenors and bureaucrats acted largely as a break on the development of struggle at the occupied Ford-Visteon plants. Indeed, in a manner analogous to the British State’s cocktail of negligence and interference when it comes to welfare provision, ‘representation’ here meant supplying unreliable legal advice to union members and fear-mongering about the repercussions of stepping beyond the law whilst failing to provide material support and funds. For an excellent account and analysis of the struggle by workers at the Ford-Visteon plant in Enfield earlier this year see Ret Marut’s, ‘A Post-Fordist Struggle: Report and reflections on the UK Ford-Visteon dispute 2009’, June 9 2009, http://libcom.org/history/report-reflections-uk-ford-visteon-dispute-2009-post-fordist-struggle

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com